12.2 Helping, Comforting, and Learning from Others in Childhood

As children grow from infancy into toddlerhood and beyond, they become increasingly mobile and capable of a wide variety of actions in their physical and social worlds. In his life-span theory of social development, Erikson (1963) divided the years from age 1 to 12 into three successive stages. These are concerned, respectively, with the development of autonomy (self-control), initiative (willingness to initiate actions), and industry (competence in completing tasks). These characteristics are all closely related to one another; they have to do with the child’s ability to control his or her own actions.

As Erikson pointed out, however, children’s actions frequently bring them into conflict with caregivers and others around them. According to Erikson, caregivers’ responses to children’s actions, and the ways by which caregivers and children resolve their conflicts, influence children’s social development. On the positive side, children may develop the ability to behave appropriately, with confidence, in ways that are satisfying both to themselves and to others. On the negative side, children may develop feelings of shame, doubt, and inferiority that interfere with autonomy, initiative, and industry. The psychologically healthy person, in Erikson’s theory, is one who responds appropriately to others’ needs without sacrificing his or her own sense of self-control. Developmental psychologists refer to such actions as prosocial behavior, voluntary behavior intended to benefit other people (Eisenberg et al., 2013), and it is to this topic we now turn.

469

The Development of Prosocial Behavior

As we’ve noted several times in this book, infants and young children are predisposed to be social. All other things being equal, infants prefer to look at faces and seem to have a special ability to process and make sense of faces; they view others as intentional agents who do things “on purpose” with specific goals in mind, and they easily form attachments with multiple people (but especially their mothers) early in life. Infants and young children are not simply oriented toward social stimuli, however. They are also disposed to behave positively, or prosocially, toward other people, and we will look at three aspects of young children’s prosocial behavior here: comforting, helping, and sharing.

The Early Emergence of Empathy and Empathic Comforting

11

According to Hoffman, how does empathy develop during infancy and early toddlerhood?

Newborn babies, as young as 2 or 3 days old, reflexively cry and show other signs of distress in response to another baby’s crying. Martin Hoffman (2000, 2007) has suggested that this tendency to feel discomfort in response to another’s expressed discomfort is a foundation for the development of empathy. Over time, the response gradually becomes less reflexive and more accompanied by thought. By about 6 months of age, babies may no longer cry immediately in response to another’s crying, but rather turn toward the distressed individual, look sad, and whimper.

Until about 15 months of age, the child’s distress when others are distressed is best referred to as egocentric empathy (Hoffman, 2007). The distressed child seeks comfort for him- or herself rather than for the other distressed person. At about 15 months, however, children begin to respond to another’s discomfort by attempting to comfort that person, and by 2 years of age they begin to succeed at such comforting (Hoffman, 2000; Knafo et al., 2008). For example, Hoffman described a case in which 2-year-old David first attempted to comfort his crying friend by giving him his (David’s) own teddy bear. When that didn’t work, David ran to the next room and returned with his friend’s teddy bear and gave it to him. The friend hugged the bear and immediately stopped crying. To behave in such an effective manner, the child must not only feel bad about another’s discomfort, but must also understand enough about the other person to know what will provide comfort.

The Young Child’s Natural Tendency to Give and Help

12

What evidence suggests that young children naturally enjoy giving? How do the !Kung use that enjoyment for moral training?

Around 12 months of age, infants routinely begin to give objects to their caregivers and to delight in games of give and take, in which the child and caregiver pass an object back and forth to each other. They do this without any special encouragement. In a series of experiments conducted in the United States, nearly every one of more than 100 infants, aged 12 to 18 months, spontaneously gave toys to an adult during brief sessions in a laboratory room (Hay & Murray, 1982; Rheingold et al., 1976). They gave toys not just to their mothers or fathers but also to unfamiliar researchers, and they gave new toys as frequently as familiar ones. They gave when an adult requested a toy by holding a hand out with palm up (the universal begging posture), and they gave when no requests were made. In another study, infants in a !Kung hunter-gatherer community were likewise observed to give objects regularly, beginning near the end of their first year of life (Bakeman et al., 1990).

470

In addition to liking to give, young children enjoy helping with adult tasks. In one study, children between 18 and 30 months old were frequently observed joining their mothers, without being asked, in such household tasks as making the bed, setting the table, and folding laundry (Rheingold, 1982). Not surprising, the older children helped more often, and more effectively, than the younger ones. In other research, experimenters sat across from 18- and 24-month-old toddlers performing some simple tasks, such as reaching for a marker or stacking books (Warneken & Tomasello, 2006). Occasionally, a mishap would occur, for example, the marker or book would fall to the floor. Children spontaneously retrieved the fallen objects, and did so more often when it looked as if the adult had made a mistake (for example, intended to stack the book but it slipped out of his hand) than when the experimenter intentionally dropped the object to the floor.

One might argue that young children’s early giving and helping are largely self-centered rather than other centered, motivated more by the child’s own needs and wishes than by the child’s perception of others’ needs and wishes. But the very fact that such actions seem to stem from the child’s own wishes is evidence that our species has evolved prosocial drives, which motivate us—with no feeling of sacrifice—to involve ourselves in positive ways with other people.

In their relationships with caregivers, young children are most often on the receiving end of acts of giving, helping, and comforting. They therefore have ample opportunity not only to witness such behaviors but also to feel their pleasurable and comforting consequences. Correlational studies indicate, not surprisingly, that children who have received the most sensitive care, and who are most securely attached to their caregivers, also demonstrate the most comforting and giving to others (Bretherton et al., 1997; Kiang et al., 2004).

Sharing

13

At about what age and under what conditions do children share?

Closely related to giving is sharing. Young children are notoriously poor sharers, especially with other children; the word “mine!” is a frequent refrain between two toddlers playing with a single toy. In fact, in one study, 84 percent of all disputes between pairs of 21-month-old children involved conflict over toys (Hay & Ross, 1982). Sharing is more common with older children, with the amount that children share of any commodity increasing with age. For example, when 5- to 14-year-old children had earned five candy bars and were told they could share some of their candy with “poor children,” a majority of children at all ages shared at least one candy bar (60 percent of 5- and 6-year-olds shared, 92 percent of 7- and 8-year-olds shared, as did 100 percent of 9- and 10-year-olds and 13- and 14-year-olds), and the number of candy bars shared increased with age (Green & Schneider, 1974).

However, just as young children will offer help and give things to others on some occasions, they also will share in many contexts. For instance, Celia Brownell and her colleagues (2009) had 18- and 25-month-old toddlers take part in a food-sharing task with an adult. Children were at one end of an apparatus that enabled them to pull on a handle to deliver a treat for themselves; or, if they chose, they could pull another handle and deliver a treat both for themselves and for the adult on the other side of the apparatus. On some trials the adult said, “I like crackers. I want a cracker.” Although the 18-month olds responded randomly on all trials, the 25-month olds shared on about 70 percent of the trials when the adult stated a desire for a cracker.

471

Young children seem especially likely to share in situations in which they need to collaborate to achieve a goal. For example, in one study, 3-year-old children were shown how to operate an apparatus in which the two children had to pull on separate ropes in order to deliver a prize. Under these conditions, children cooperated on 70 percent of the trials, and shared the rewards equally on greater than 80 percent of these trials (Warneken et al., 2011).

In other situations in which resources (stickers or food) are distributed among children, even 3-year-olds realize when they are getting an unfair deal, although they are less apt to complain when they get the lion’s share of the resources (LoBue et al., 2010). However, when children are in control of the resources and given the choice to share or not, most 4- and 5-year-old children share, but continue to keep more resources for themselves than they give to others (Benenson et al., 2007). As they get older, children are increasingly likely to see fairness in terms of equitable distributions (that is, rewards according to effort expended). Young children’s fair distribution of resources is also related to theory of mind. In one study, preschool children who passed false-belief tasks (see Chapter 11) were more likely to make a fair distribution of resources between themselves and a peer than children who failed such tasks (Takagishi et al., 2010).

Social Learning

Given the extent to which children are oriented toward their social environment, it is not surprising that much of what they learn is accomplished in a social context. We discussed social learning in Chapter 4, providing an outline of Bandura’s social-learning theory (renamed social-cognitive theory), which emphasized the process of vicarious reinforcement—the ability to learn from the consequences of others’ actions—and differentiated between different types of observational learning. Although Bandura’s influential theory emphasized the role of imitation—the ability to understand a model’s goal and to reproduce those behaviors in order to achieve those goals—there are other forms of social learning. One such form is emulation, which involves observing another individual achieve some goal, then attaining that same goal by one’s own means. As described in Chapter 4, emulation has been observed in chimpanzees when one individual sees another picking up and dropping a log to reveal tasty ants, and the first chimpanzee subsequently bounces up and down on the log to access the ants.

Overimitation

14

What is overimitation, who engages in it, and why might it be adaptive?

Like chimpanzees, children of about 2 years of age and younger frequently engage in emulation. They seem to understand the goal a model has in mind, but do not restrict themselves to using the same behaviors as the model did to achieve that goal (McGuigan & Whiten, 2009; Nielsen, 2006). Things begin to change around age 3, however. A number of studies has convincingly demonstrated that beginning about this time most children faithfully repeat the actions of a model, even if many of those actions are irrelevant and if there is a more efficient way to solve the problem. Such overimitation was observed in a study by Derek Lyons and his colleagues (2007), who showed preschool children how to open a transparent container to get a toy that was locked inside. Some of the actions of the model were clearly relevant to opening the container, such as unscrewing its lid, whereas others were clearly irrelevant, such as tapping the side of the container with a feather. When later given a chance to retrieve the toy themselves, most children copied both the relevant and irrelevant actions, even though they were able to tell the experimenter which actions were necessary and which were “silly,” and when they were asked, to avoid the “silly” ones. Overimitation is not limited to children from Western culture but has also been observed in 2- to 6-year-old Kalahari Bushman children (Nielsen & Tomaselli, 2010). Moreover, although older children and adults should surely know better, even they engage in overimitation. In one study using a transparent container that had to be opened to retrieve an object, 3- and 5-year-old children and adults observed models performing both relevant and irrelevant actions on the container. Copying irrelevant actions increased with age, with the adults actually displaying less efficient performance than the children (McGuigan et al., 2011).

472

Children (and adults) are not necessarily blind mimics, however. For example, 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old children in one study were less apt to copy irrelevant actions in attempting to get a toy out of a container when the adult model made it clear that such actions were accidental (saying, “Whoops! I didn’t mean to do that!”) than when the actions were cued as intentional (saying, “There!”) (Gardiner et al., 2011).

Yet, overimitation seems to be the rule rather than the exception. Why should children (and adults) copy irrelevant actions when a more effective means is seemingly available to them? One explanation is that humans age 3 and older generally believe that models are trustworthy and that they are performing all the actions for a purpose. Recall from Chapter 11 that infants in the latter part of the first year begin to see other people as intentional agents, doing things “on purpose” to achieve specific goals. Such a stance makes everything that people do in the process of achieving some outcome relevant, and makes children’s nearly automatic copying of all of a model’s behavior adaptive. In most cases, what a model does is important to attaining a goal, and any effort children expend beyond what is necessary to complete a task is more than compensated by the greater efficiency afforded by social learning, as opposed to trial-and-error learning. This may be especially important for humans relative to other social animals because children must learn about thousands of artifacts, all cultural inventions. An efficient way to acquire such knowledge is to imitate modeled behaviors exactly with respect to the artifacts (Whiten et al., 2009). Consistent with this interpretation, children seem to think that modeled actions on objects are normative. For example, 3- to 5-year-old children corrected a puppet that omitted unnecessary actions previously performed by an adult, protesting that the puppet was “doing it wrong” (Kenward, 2012).

Learning from Other Children

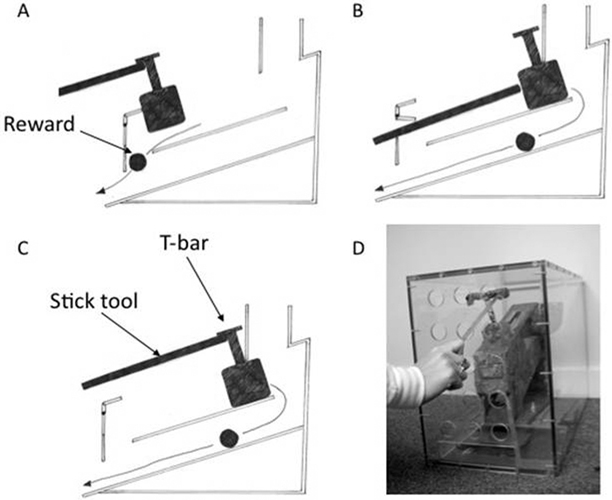

Although children surely learn much from watching adults, they also learn from other children. For example, in one study by Lydia Hopper and her colleagues (2010), one preschooler was shown how to work an apparatus the researchers called pan-pipes, shown in Figure 12.4, using a stick to retrieve a treat. There are three ways to successfully operate the pan-pipes to get the reward: (a) the Lift method, in which the stick is inserted into a hole to lift the T-bar; (b) the Poke method, in which the stick is inserted into a different hole, poking the T-bar; and (c) the Push-Lift method, in which the stick is used to push and then slide the T-bar. One child was shown the Lift method. This child then served as the model for another child, who in turn served as a model for another child, and so on for a total of 20 children. All 20 children learned the Lift method, demonstrating the fidelity with which children can transmit information from one to another. In contrast, when another group of children was shown the pan-pipes and asked to figure out how to get the treat out, only 3 of 16 succeeded.

15

What evidence is there that children learn new skills from watching other children?

But preschool children do not often deliberately teach a skill to another child. A more common occurrence, in a preschool classroom anyway, is one child performing some task while classmates happen to see the outcome. This was examined in a study by Andrew Whiten and Emma Flynn (2010), who taught one child in each of two preschool classrooms either the Lift or the Poke method for working the pan-pipes. They then placed the pan-pipes into the child’s classroom and watched what happened. Most of the children in a classroom tried to operate the pan-pipes, usually after watching the trained child receive a treat, and 83 percent of children who did so were successful. Most children initially used the method the trained child had used and continued to use this method for several days. However, after a few days, several children learned alternate ways of operating the pan-pipes (Lift if they had originally had used Poke and vice versa), and this new method, too, spread to other children in the classroom. Not surprising, in addition to simply modeling how to get a treat from the pan-pipes, many children talked about what they were doing, trying to teach other children how to operate the apparatus. This research shows that young children have a number of social-learning abilities at their disposal and that a skill learned by one child will be transmitted to other children, sometimes with fidelity and sometimes with modifications.

473

SECTION REVIEW

The child’s species-typical drives and emotions, and interactions with caregivers, promote social development.

Prosocial Behavior

- The development of empathy during the second year causes children to base actions of giving, helping, sharing, and comforting on an understanding of and concern for others’ needs and feelings.

- Young children are predisposed to help, give, and even share; they give objects spontaneously to others beginning at about 12 months of age.

Social Learning

- Children learn much in social contexts and by 3 years of age tend to imitate all actions a model displays, both relevant and irrelevant (overimitation).

- Children transmit skills to one another, usually with high fidelity.

474