12.3 Parenting Styles

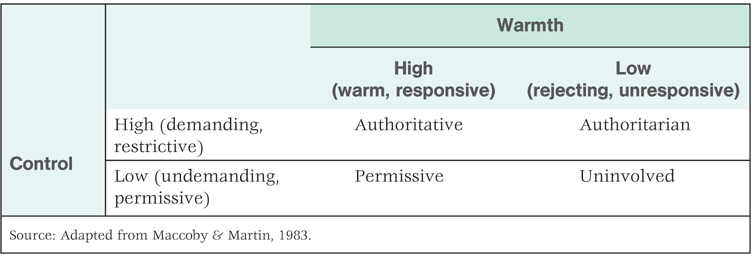

For some animals, the offspring are on their own after birth. This, of course, is not the case with mammals, whose sole source of food is their mother’s milk. Yet, once infants are weaned the young of many mammals must fend for themselves, whereas for other mammals, including all primates, mom (and for a handful of primates, dad) continue to have some “parenting” obligations. This is especially true for humans, whose extended period of immaturity makes it necessary for them to be cared for long after they are no longer dependent on mother’s milk for survival. There are many ways in which parents interact with the children on the way to adulthood, and these are often characterized as parenting styles. Psychologists describe parenting style in terms of two dimensions: (1) the degree of warmth a parent shows toward a child, reflected by being loving and attentive to children and their needs, and (2) the degree of control a parent attempts to exert over a child’s behavior. Parenting style can be divided into four general types, depending where a parent falls (high versus low) on these two dimensions (see Table 12.1).

Parenting styles can be classified according to warmth (high versus low) that parents display and the amount of control (high versus low) they try to impose on their children’s behavior.

Correlations Between Disciplinary Styles and Children’s Behavior

16

What are the four general parenting styles psychologists have identified, and how do they affect children’s psychological development?

The best-known, pioneering study of parenting styles was conducted many years ago by Diana Baumrind (1967, 1971). Baumrind assessed the behavior of young children by observing them at nursery schools and in their homes, and she assessed parents’ behaviors toward their children through interviews and home observations. On the basis of the latter assessments, she classified parents into three groups:

- Authoritarian parents strongly value obedience for its own sake and use a high degree of power assertion to control their children (low warmth, high control).

- Authoritative parents are less concerned with obedience for its own sake and more concerned that their children learn and abide by basic principles of right and wrong (high warmth, high control).

- Permissive parents are most tolerant of their children’s disruptive actions and least likely to discipline them at all. The responses they do show to their children’s misbehavior seem to be manifestations of their own frustration more than reasoned attempts at correction (high warmth, low control).

Eleanor Maccoby and John Martin (1983) completed the matrix, adding uninvolved (or neglectful) parenting. These parents are disengaged from their children, emotionally cold, and demand little from their offspring (low warmth, low control).

Physical punishment such as spanking is associated with authoritarian parenting more than with other styles. Although spanking as a disciplinary tool is controversial, a 2007 ABC News poll found that it is used, at least occasionally, by approximately 65 percent of American parents. Spanking is against the law in many countries including Austria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Norway, and Sweden (Gershoff, 2002). Most child psychologists advocate against spanking, but some propose that the negative effects of spanking can be attributed to only the most severe forms of physical punishment and that the across-the-board sanction against spanking is not warranted by the data (Baumrind et al., 2002).

475

Baumrind and others (Collins & Steinberg, 2006) found that children of authoritative parents exhibited the most positive qualities. They were friendlier, happier, more cooperative, and less likely to disrupt others’ activities than were children of either authoritarian or permissive parents. In a follow-up study of the same children, the advantages for those with authoritative parents were still present at age 9 (Baumrind, 1986). In contrast, children of authoritarian parents often perform poorly in school, have low self-esteem, and are more apt to be rejected by their school peers (Coopersmith, 1967; Pettit et al., 1988), whereas children of permissive parents tend to be impulsive and aggressive, often acting out of control (Lamborn et al., 1991). Not surprising, children of uninvolved parents typically fare the worst. In adolescence, they often show a broad range of problem behaviors, including sexual promiscuity, antisocial behavior, drug use, and internalizing problems such as depression and social withdrawal (Baumrind, 1991; Lamborn et al., 1991).

The Cause-Effect Problem in Relating Parenting Style to Children’s Behavior

As always, we must be cautious in drawing causal inferences from correlational research. It is tempting to conclude from studies such as Baumrind’s that the positive parenting style caused the good behavior of the offspring, but the opposite causal relationship may be just as plausible. Some children are temperamentally less cooperative and more disruptive than others, and such behavior may elicit harsh, power-assertive discipline and reduced warmth from parents. Several studies have shown that children with different temperaments do, indeed, elicit different disciplinary styles from their parents (Jaffee et al., 2004; O’Connor et al., 1998).

The best evidence that parenting styles influence children’s development comes from experiments that modify, through training, the styles of one group of parents and then compare their offspring to those of otherwise similar parents who did not receive such training. In one such experiment, divorced mothers of 6- to 8-year-old boys were assigned either to a training condition, in which they were taught how to use firm but kind methods of discipline, or to a comparison condition, in which no such training was given. Assessments a year later showed that the sons whose mothers had undergone training had better relationships with their mothers, rated themselves as happier, and were rated by their teachers as friendlier and more cooperative than was the case for the sons of the comparison mothers (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999). Further assessment, 3 years later, revealed significantly less delinquent behavior by sons of the trained mothers compared to those of the untrained mothers.

SECTION REVIEW

Parenting Styles

- Baumrind found that children of parents with an authoritative disciplinary style were happier, friendlier, and more cooperative than children of parents with either authoritarian or permissive styles.

- Though Baumrind’s study was correlational, experimental research also supports Baumrind’s ideas about effective disciplinary styles.

476