12.4 The Roles of Play and Gender in Development

Parents play important roles in children’s social development, but so do peers. Indeed, if developmental psychology were an endeavor pursued by children rather than by adults, we suspect that research would focus more than it currently does on children’s relationships with one another and less on their relationships with adults. Parents and other caregivers provide a base from which children grow, but peers are the targets toward which children are oriented and about which they often have the most conscious concerns. A mother and father want their daughter to wear a certain pair of shoes, but the neighborhood children think the shoes are “geeky” and a different style is “cool.” Which shoes will the girl want to wear? From an evolutionary perspective, children’s strong orientation toward peers—that is, toward members of their own generation—makes sense. After all, it is the peer group, not the parental group, that will provide the child’s most direct future collaborators in life-sustaining work and reproduction.

Across cultures and over the span of history, a child’s social world is and has been a world largely of other children. In most cultures for which data are available, children beyond the age of 4 or 5 years spend more of their daytime hours with other children than with adults (Konner, 1975; Whiting & Edwards, 1988). What are they doing together? Mostly they are playing. In every culture that has been studied, children play when they have the opportunity, and their play takes certain universal forms (Pellegrini & Bjorklund, 2004; Power, 2000). It is also true that in every culture that has been studied, children tend to segregate themselves by sex when they play: Boys play mostly with boys, and girls play mostly with girls (Maccoby, 1998, 2002; Whiting & Edwards, 1988). Through playing with others of their own sex, children develop the gender-specific skills and attitudes of their culture.

Developmental Functions of Play

Chapter 4 presented evidence that play evolved in mammals as a means to ensure that the young of the species will practice and become expert at skills that are necessary for their long-term survival and reproduction. Young mammals play at fleeing, chasing, fighting, stalking, and nurturing. The play of young humans is often like that of other young mammals and appears to serve many of the same functions. Let us explore these functions from the standpoint of human development.

Play Is a Vehicle for Acquiring Skills

17

What are some universal forms of human play, and what developmental functions do they seem to serve?

Children all over the world play chase games, which promote physical stamina, agility, and the development of strategies to avoid getting caught. Play nurturing, often with dolls or other infant substitutes rather than real infants, and play fighting are also universal, and everywhere the former is more prevalent among girls and the latter is more prevalent among boys (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1989).

Other universal forms of human play are specific to our species and help children develop human-specific skills (Pellegrini, 2013; Power, 2000). Children everywhere become good at making things with their hands through constructive play (play at making things), become skilled with language through word play, and exercise their imaginations and planning abilities through social fantasy play. In cultures where children can directly observe the sustenance activities of adults, children focus much of their play on those activities (Gray, 2009; Kamei, 2005). For instance, young boys in hunter-gatherer cultures spend enormous amounts of time at play hunting, such as shooting at butterflies with bows and arrows, and develop great skill in the process.

477

18

How do observations of two Mexican villages illustrate the role of play in the transmission of cultural skills and values from one generation to the next? How might play promote cultural advancement?

In a study of two Mexican villages, Douglas Fry (1992) showed how children’s play reflects and may help transmit a culture’s values and skills. The two villages were alike in many ways, and the similarity was reflected in aspects of the children’s play. In both communities, for example, boys made toy plows with sticks and used them to furrow the earth as their fathers worked at real plowing in the fields, and girls made pretend tortillas, mimicking their mothers. In one respect, however, the two communities differed markedly.

For generations in La Paz, the people had prided themselves on their peacefulness and nonviolence, but the same was not true in San Andrés (the villages’ names are pseudonyms). Often in San Andrés, but rarely in La Paz, children saw their parents fight physically, heard of fights or even murders among men stemming from sexual jealousy, and were themselves victims of beatings administered by their parents. In his systematic study of the everyday activities of 3- to 8-year-olds, Fry observed that the San Andrés children engaged in about twice as much serious fighting, and about three times as much play fighting, as the La Paz children. When fighting is common in a culture, fighting will apparently be understood intuitively by children as a skill to be practiced not just in anger but also in play, for fun.

Children’s play can help create and advance culture as well as reflect it. When the computer revolution began in North America, children, who usually had no use for computers other than play, were in many families the first to become adept with the new technology. They taught their parents how to use computers. Some of the same children—as young adults, but still in the spirit of play—invented new and better computers and computer programs. Many years ago the Dutch cultural historian Johan Huizinga (1944/1970) wrote a book contending that much, if not most, of what we call “high culture”—including art, literature, philosophy, and legal systems—arose originally in the spirit of play where play was extended from childhood into adulthood.

Play as a Vehicle for Learning About Rules and Acquiring Self-Control

In addition to practicing species-typical and culturally valued skills, play may enable children to acquire more advanced understandings of rules and social roles and greater self-control. Both Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky—the famous developmental psychologists introduced in Chapter 11—developed theories along these lines.

19

What ideas did Piaget and Vygotsky present concerning the value of play in social development? What evidence supports their ideas?

In his book The Moral Judgment of the Child, Piaget (1932/1965) argued that unsupervised play with peers is crucial to moral development. He observed that adults use their superior power to settle children’s disputes, but when adults are not present, children argue out their disagreements and acquire a new understanding of rules based on reason rather than authority. They learn, for example, that rules of games such as marbles are not immutable but are human contrivances designed to make the game more interesting and fair and can be changed if everyone agrees. By extension, this helps them understand that the same is true of the social conventions and laws that govern life in democratic societies. Consistent with Piaget’s theory, Ann Kruger (1992) found that children showed greater advances in moral reasoning when they discussed social dilemmas with their peers than when they discussed the same dilemmas with their parents. With peers, children engaged actively and thoughtfully in the discussions, which led to a higher level of moral reasoning; with parents they were far more passive and less thoughtful.

In an essay on the value of play, Vygotsky (1933/1978) theorized that children learn through play how to control their own impulses and to abide by socially agreed-upon rules and roles—an ability that is crucial to social life. He pointed out that, contrary to common belief, play is not free and spontaneous but is always governed by rules that define the range of permissible actions for each participant. In real life, young children behave spontaneously—they cry when they are hurt, laugh when they are happy, and express their immediate desires. But in play they must suppress their spontaneous urges and behave in ways prescribed by the rules of the game or the role they have agreed to play. Consider, for example, children playing a game of “house,” in which one child is the mommy, another is the baby, and another is the dog. To play this game, each child must keep in mind a conscious conception of how a mommy, a baby, or a dog behaves and must govern his or her actions in accordance with that conception.

478

Play, then, according to Vygotsky, has this paradoxical quality: Children freely enter into it, but in doing so they give up some of their freedom. In Vygotsky’s view, play in humans evolved at least partly as a means of practicing self-discipline of the sort that is needed to follow social conventions and rules.

Consistent with Vygotsky’s view, researchers have found that young children put great effort into planning and enforcing rules in their social fantasy play (Furth, 1996; Garvey, 1990). Children who break the rules—who act like themselves rather than the roles they have agreed to play—are sharply reminded by the others of what they are supposed to do: “Dogs don’t sit at the table; you have to get under the table.” Also in line with Vygotsky’s view, researchers have found positive correlations between the amount of social fantasy play that children engage in and subsequent ratings of their social competence and self-control (Connolly & Doyle, 1984; Elias & Berk, 2002).

The Special Value of Age-Mixed Play

In age-graded school settings, such as recess, children play almost entirely with others who are about the same age as themselves. But in neighborhood settings in our culture, and even more so in cultures that don’t have age-graded schools (Whiting & Edwards, 1988), children often play in groups with age spans of several years. Indeed, as Konner (1975) has pointed out, the biological underpinnings of human play must have evolved under conditions in which age-mixed play predominated. Hunter-gatherer communities are small, and births within them are widely spaced, so a given child rarely has more than one or two potential playmates who are within a year of his or her own age.

20

What features of age-mixed play may make it particularly valuable to children’s development?

Psychologists have paid relatively little attention to age-mixed play, but the work that has been done suggests that such play is often qualitatively different from play among age mates (Gray, 2013). One difference is that it is less competitive; there is less concern about who is best (Feldman, 1997; Feldman & Gray, 1999). An 11-year-old has nothing to gain by proving him- or herself stronger, smarter, or more skilled than a 7-year-old, and the 7-year-old has no chance of proving the reverse. Konner (1972) noted that age-mixed rough-and-tumble play among the !Kung children whom he observed might better be called “gentle-and-tumble” because an implicit rule is that participants must control their movements so that they do not hurt a younger child.

I (Peter Gray) have studied age-mixed play at an alternative school in the United States, where children from age 4 to 18 intermingle freely. At this school, age mixing appears to be a primary vehicle of education (Greenberg, 1992). Young children acquire more advanced interests and skills by observing and interacting with older children, and older children develop skills at nurturing and consolidate some of their own knowledge by helping younger children. We observed this happening in a wide variety of forms of play, including rough-and-tumble, sports of various types, board games, computer play, constructive play (such as play with blocks or with art materials), and fantasy play (Gray & Feldman, 2004). In each of these contexts, to make the game more fun, older children helped younger children understand rules and strategies. Studies of play among siblings who differ by several years in age have yielded similar findings (Brody, 2004).

Unfortunately, our age-graded system of schooling, coupled with the decline in neighborhood play that has occurred in recent decades, deprives many children in our culture of a powerful natural source of education—the opportunity to interact closely, over prolonged periods, with other children who are substantially older or younger than themselves.

479

Gender Differences in Social Development

Life is not the same for girls and boys. That is true not just in our culture but in every culture that has been studied (Maccoby, 1998; Whiting & Edwards, 1988). To some degree, the differences are biological in origin, mediated by hormones (Else-Quest et al., 2006; also see Chapter 6). But, as the anthropologist Margaret Mead (1935) noted long ago, the differences also vary from culture to culture and over time within a given culture in ways that cannot be explained by biology alone.

Gender Differences in Interactions with Caregivers

Even in early infancy, boys and girls, on average, behave somewhat differently from each other. On average, newborn boys are more irritable and less responsive to caregivers’ voices and faces than are newborn girls (Hittelman & Dickes, 1979; Osofsky & O’Connell, 1977). By 6 months of age, boys squirm more and show more facial expressions of anger than do girls when confined in an infant seat, and girls show more facial expressions of interest and less fussing than do boys when interacting with their mothers (Weinberg et al., 1999). By 13 to 15 months of age, girls are more likely than are boys to comply with their mothers’ requests (Kochanska et al., 1998). By 17 months, boys show significantly more physical aggression than do girls (Baillargeon et al., 2007).

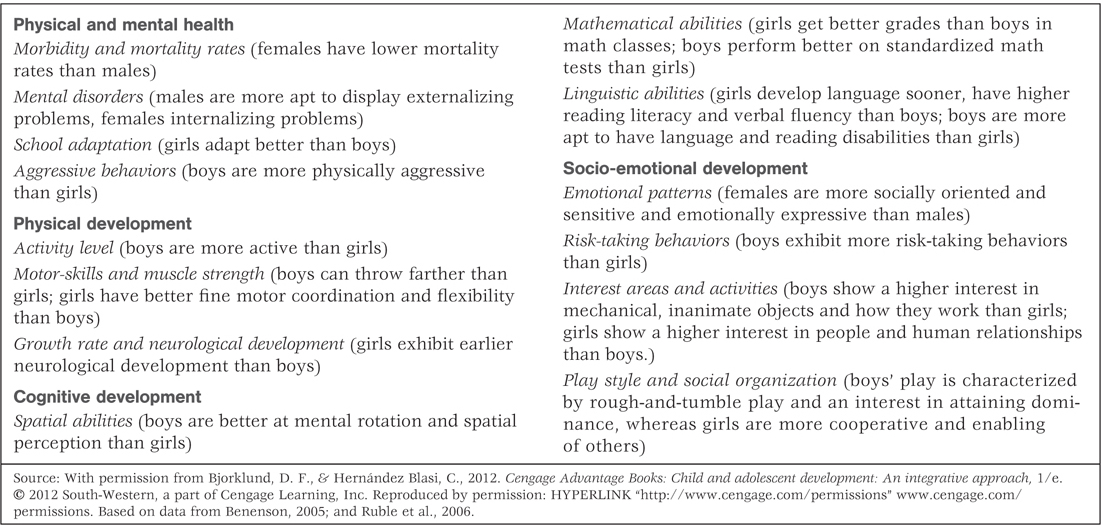

Table 12.2 presents a list of several frequently reported sex differences in each of four general areas: (a) physical and mental health; (b) physical development; (c) cognitive development; and (d) socioemotional development. In most of these cases, the differences between boys and girls are small, and there is much overlap (for example, many boys adapt better to school than the average girl, although on average girls have an advantage). The presence of reliable sex differences does not tell us the origin of the differences—that is, whether they are mainly biological or mainly cultural—only that they exist and are usually found across cultures.

Frequently reported sex differences

480

21

What are some of the ways that girls and boys are treated differently by adults in our culture, and how might such treatment promote different developmental consequences?

Parents and other caregivers behave differently toward girls and boys, beginning at birth. They are, on average, more gentle with girls than with boys; they are more likely to talk to girls and to jostle boys (Maccoby, 1998). Such differences in treatment may in part reflect caregivers’ sensitivity and responsiveness to actual differences in the behaviors and preferences of the infant girls and boys, but it also reflects adult expectations that are independent of the infants’ behaviors and preferences. In one study, mothers interacted more closely with, talked in a more conversational manner to, and gave fewer direct commands to their infant daughters than to their infant sons, even though the researchers could find no differences in the infants’ behavior (Clearfield & Nelson, 2006). In another study, mothers were asked to hold a 6-month-old female infant, who in some cases was dressed as a girl and introduced as Beth, and in other cases was dressed as a boy and introduced as Adam. The mothers talked to Beth more than to Adam, and gave Adam more direct gazes unaccompanied by talk (Culp et al., 1983).

Other research suggests that, regardless of the child’s age, adults offer help and comfort more often to girls than to boys and more often expect boys to solve problems on their own. In one experiment, college students were quicker to call for help for a crying infant if they thought it was a girl than if they thought it was a boy (Hron-Stewart, 1988). In another study, mothers of 2-year-old daughters helped their toddlers in problem-solving tasks more than did mothers of 2-year-old sons (Hron-Stewart, 1988). Theorists have speculated that the relatively warmer treatment of girls and greater expectations of self-reliance for boys may lead girls to become more affectionate and sociable and boys to become more self-reliant than they otherwise would (Dweck et al., 1978; MacDonald, 1992).

Adults’ assumptions about the different interests and abilities of girls and boys may play a role in the types of careers that the two sexes eventually choose. In particular, parents and teachers often express the belief that math and science are harder and less interesting for girls than for boys. A number of studies suggest that such different expectations influence the way that adults talk about science and math to boys and girls, even when measures of children’s abilities and self-reported interests show no such differences (Lindberg et al., 2008; Tenenbaum & Leaper, 2003).

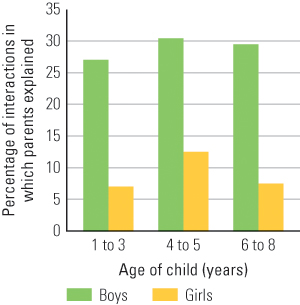

In one study, parents and their young children were observed at interactive exhibits at a science museum (Crowley et al., 2001). The main finding was that parents, both fathers and mothers, were far more likely to explain something about the workings of the exhibits, or the underlying principles being demonstrated, to their sons than to their daughters. This occurred regardless of the age of the child (see Figure 12.5) and despite the fact that the researchers could find no evidence, from analyzing the children’s behavior and questions, that the sons were more interested in the exhibits or in the principles being demonstrated than were the daughters. Perhaps such differential treatment helps explain why many more men than women choose careers in the physical sciences.

Gender Identity and Its Effects on Children’s Behavior

22

How do children mold themselves according to their understanding of gender differences?

Children’s gender development may be influenced by adults’ differential treatment, but children also actively mold themselves to behave according to their culture’s gender conceptions. By the age of 4 or 5, most children have learned quite clearly their culture’s stereotypes of male and female roles (Martin & Ruble, 2004; Williams & Best, 1990). They also recognize that they themselves are one gender or the other and always will be, an understanding referred to as gender identity (Kohlberg, 1966). Once they have this understanding, children in all cultures seem to become concerned about projecting themselves as clearly male or female. They attend more closely to people of their own gender and model their behavior accordingly, often in ways that exaggerate the male-female differences they see. When required to carry out a chore that they regard as gender inappropriate, they often do so in a style that clearly distinguishes them from the other gender. For example, in a culture where fetching water is considered women’s work, young boys who are asked to fetch water carry it in a very different manner from that used by women and girls (Whiting & Edwards, 1988).

481

From a biological perspective, gender is not an arbitrary concept but is linked to sex, which is linked to reproduction. A tendency toward gender identity may well have evolved as an active assertion of one’s sex as well as a means of acquiring culture-specific gender roles. By acting “girlish” and “boyish,” girls and boys clearly announce that they are on their way to becoming sexually viable women and men. Researchers have found that young children often create or overgeneralize gender differences, with this being more extreme in boys than in girls (Martin & Ruble, 2004). For example, when preschoolers were told that a particular boy liked a certain sofa and a particular girl liked a certain table, they generalized this to assume that all boys would like the sofa and all girls would like the table (Bauer & Coyne, 1997).

Children’s Self-Imposed Gender Segregation

23

What function might children’s self-segregation by gender serve? In our culture, why might boys avoid playing with girls more than the reverse?

In all cultures that have been studied, boys and girls play primarily with others of their own sex (Maccoby, 1998; Pellegrini et al., 2007), and, at least in our culture, such segregation is more common in activities structured by children themselves than in activities structured by adults (Berk & Lewis, 1977; Maccoby, 1990). Even 3-year-olds have been observed to prefer same-sex playmates to opposite-sex playmates (Maccoby & Jacklin, 1987), but the peak of gender segregation, observed in many different settings and cultures, occurs in the age range of 8 to 11 years (Gray & Feldman, 1997; Hartup, 1983; Whiting & Edwards, 1988). In their separate playgroups, boys practice what they perceive to be the masculine activities of their culture, and girls practice what they perceive to be the feminine activities of their culture.

In some settings, children reinforce gender segregation by ridiculing those who cross gender lines, but this ridicule is not symmetrical. Boys who play with girls are much more likely to be teased and taunted by both gender groups than are girls who play with boys (Petitpas & Champagne, 2000; Thorne, 1993). Indeed, girls who prefer to play with boys are often referred to with approval as “tomboys” and retain their popularity with both sexes. Boys who prefer to play with girls are not treated so benignly. Terms like “sissy” or “pansy” are never spoken with approval. Adults, too, express much more concern about boys who play with girls or adopt girlish traits than they do about girls who play with boys or adopt boyish traits (Martin, 1990). Perhaps the difference reflects the culture’s overall view that male roles are superior to female roles, which might also help explain why, over the past several decades, many women in our culture have moved into roles that were once regarded as exclusively masculine, while relatively fewer men have moved into roles traditionally considered feminine.

482

Gender Differences in Styles of Play

24

In what ways can girls’ and boys’ peer groups be thought of as separate subcultures? Why might differences in boys’ and girls’ play be greater in age-segregated settings than in age-mixed settings?

Girls and boys tend to play differently as well as separately, and the differences are in some ways consistent from culture to culture (Rose & Rudolph, 2006; Whiting & Edwards, 1988). Some social scientists consider boys’ and girls’ peer groups to be so distinct that they constitute separate subcultures, each with its own values, directing its members along different developmental lines (Maccoby, 1998, 2002; Maltz & Borker, 1982).

The world of boys has been characterized as consisting of relatively large, hierarchically organized groups in which individuals or coalitions attempt to prove their superiority through competitive games, teasing, and boasting. A prototypical boys’ game is “King of the Hill,” the goal of which is to stand on top and push everyone else down. The world of girls has been characterized as consisting of smaller, more intimate groups, in which cooperative forms of play predominate and competition, although not absent, is more subtle. A prototypical girls’ game is jump rope, the goal of which is to keep the action going as long as possible through the coordinated activities of the rope twirlers and the jumper.

The “two-worlds” concept may exaggerate somewhat the typical differences in the social experiences of boys and girls. Most research supporting the concept has been conducted in age-segregated settings, such as school playgrounds and summer camps. At home and in neighborhoods, children more often play in age-mixed groups. As noted earlier, age-mixed play generally centers less on winning and losing than does same-age play, so age mixing reduces the difference in competitiveness between boys’ and girls’ play. Moreover, several studies indicate that boys and girls play together more often in age-mixed groups than in age-segregated groups (Ellis et al., 1981; Gray & Feldman, 1997).

Whether or not they play together, boys and girls are certainly interested in each other. On school playgrounds, for example, the separate boys’ and girls’ groups interact frequently, usually in teasing ways (Thorne, 1993). That interest begins to peak, and interactions between the sexes take on a new dimension, as children enter adolescence.

Blue Magic Photography/E+/Getty Images

483

SECTION REVIEW

Play with other children, mixed by age and by gender, influences the child’s development.

Developing Through Play

- Children everywhere play in ways that promote the development of skills needed for their survival. These include culture-specific skills, acquired by observing adults.

- Contemporary research supports Piaget’s view that children learn about rules and become better moral reasoners through play, and Vygotsky’s view that children develop self-control through play.

- Age-mixed play appears to be less competitive and more conducive to teaching, learning, and development of nurturing skills than is play among age mates.

Gender and Social Development

- There are many reliable sex differences in mental and physical health, physical development, cognitive development, and social-emotional development, although the magnitude of these differences is often quite small.

- Adults treat girls and boys differently beginning at birth, at least partly on the basis of socially grounded beliefs about gender. This may help to create or widen some gender differences.

- Once gender identity is established, by age 4 or 5, children attend to and mimic the culturally appropriate behaviors for their gender. They also exaggerate gender stereotypes and play increasingly with same-sex peers.

- Boys’ and girls’ groups are in some ways different subcultures. Boys tend to play competitively, in relatively large, hierarchical groups. Girls play more cooperatively, in smaller, more intimate groups. These differences may be muted in age-mixed play.