12.6 Adulthood: Finding Satisfaction in Love and Work

In his life-span theory, Erikson (1963) proposed that establishing intimate, caring relationships and finding fulfillment in work are the main tasks of early and middle adulthood. In this respect he was following the lead of Sigmund Freud (1935/1960), who defined emotional maturity as the capacity to love and to work. Some psychologists believe that adult development follows a predictable sequence of crises or problems to be resolved (Erikson, 1963; Levinson, 1986), while others contend that the course of adulthood in our modern culture is extraordinarily variable and unpredictable (Neugarten, 1979, 1984). But in essentially every psychological theory of adult development, caring and working are the two threads that weave the fabric of adulthood.

Love

We are a romantic species. In every culture for which data are available, people describe themselves as falling in love (Fisher, 2004; Jankowiak & Fischer, 1992; see Chapter 6 for a discussion of the biology of love). We are also a marrying species. In every culture, adults of child-producing age enter into long-term unions sanctioned by law or social custom, in which the two members implicitly or explicitly promise to care for each other and the offspring they produce (Fisher, 1992; Rodseth et al., 1991), although cultures vary greatly in the degree to which people abide by those promises. Love and marriage do not necessarily go together, but they often do, and in most cultures their combination is considered ideal. In some cultures people fall in love and then get married; in others they get married—through an arrangement made by the couple’s parents—and then, if fate works as hoped for, fall in love. Researchers have attempted to understand the underlying psychological elements of romantic love and to learn why some marriages are happy and others are not.

Romantic Love Viewed as Adult Attachment

33

How is romantic love like infant attachment? What evidence suggests continuity in attachment quality between infancy and adulthood?

Romantic love is similar in form, and perhaps in underlying mechanism, to the attachment that infants develop with their parents (Diamond, 2004; Hazan & Shaver, 1994). Close physical contact, caressing, and gazing into each other’s eyes are crucial to the early formation of both types of relationships, and lovers’ communications often include cooing and baby talk. A sense of fusion with the other reigns when all is well, and a feeling of exclusivity—that the other person could not be replaced by anyone else—prevails. The partners feel most secure and confident when they are together and may show physiological evidence of distress when separated (Feeney & Kirkpatrick, 1996).

The emotional bond is not simply a by-product of shared pleasures. In long-married couples it may exist even when the two have few interests in common. Sometimes the bond reveals its full intensity only after separation or divorce or the death of one partner. The experience of losing one’s partner typically involves intense anxiety, depression, and feelings of loneliness or emptiness that are not relieved even by highly supportive friends and an active social life (Stroebe et al., 1996; Weiss, 1975).

As with infants’ attachments with their caregivers, the attachments that adults form with romantic partners can be classified as secure (characterized by comfort), anxious (characterized by excessive worry about love or lack of it from the partner), or avoidant (characterized by little expression of intimacy or by ambivalence about commitment) (Kirkpatrick, 2005). Studies using questionnaires and interviews have revealed continuity between people’s descriptions of their adult romantic attachments and their recollections of their childhood relationships with their parents (Fraley, 2002; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). People who recall their relationships with parents as warm and secure typically describe their romantic relationships in similar terms, and those who recall anxieties and ambiguities in their relationships with parents tend to describe analogous anxieties and ambiguities in their romances. Such continuity could stem from a number of possible causes, including a tendency for adult experiences to color the person’s memories of childhood. Most attachment researchers, however, interpret it as support for a theory developed by Bowlby (1980), who suggested that people form mental models of close relationships based on their early experiences with their primary caregivers and then carry those models into their adult relationships (Fraley & Brumbaugh, 2004).

495

Ingredients of Marital Success

In the sanitized version of the fairy tale (but not in the Grimm brothers’ original), love allows the frog prince and the child princess to transform each other into perfect human adults who marry and live happily ever after. Reality is not like that. Roughly half of new marriages in North America are predicted to end in divorce (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002), and even among couples who don’t divorce, many are unhappy in marriage. Why do some marriages work while others fail?

34

What are some characteristics of happily married couples? Why might marital happiness depend even more on the husband’s capacity to adjust than on the wife’s?

In interviews and on questionnaires, happily married partners consistently say that they like each other; they think of themselves not just as husband and wife but also as best friends and confidants (Buehlman et al., 1992; Lauer & Lauer, 1985). They use the term we more than I as they describe their activities, and they tend to value their interdependence more than their independence. They also talk about their individual commitment to the marriage, their willingness to go more than halfway to carry the relationship through difficult times.

Happily married couples apparently argue as often as unhappily married couples do, but they argue more constructively (Gottman, 1994; Gottman & Krokoff, 1989). They genuinely listen to each other, focus on solving the problem rather than “winning” or proving the other wrong, show respect rather than contempt for each other’s views, refrain from bringing up past hurts or grievances that are irrelevant to the current issue, and intersperse their arguments with positive comments and humor to reduce the tension. Disagreement or stress tends to draw them together, in an effort to resolve the problem and to comfort each other, rather than to drive them apart (Murray et al., 2003).

In happy marriages, both partners are sensitive to the unstated feelings and needs of the other (Gottman, 1998; Mirgain & Cordova, 2007). In contrast, in unhappy marriages, there is often a lack of symmetry in this regard; the wife perceives and responds to the husband’s unspoken needs, but the husband does not perceive and respond to hers (Gottman, 1994, 1998). Perhaps this helps explain why, in unhappy marriages, the wife typically feels more unhappy and manifests more physiological distress than does her partner (Gottman, 1994; Levenson et al., 1993). Such observations bring to mind the differing styles of interaction and communication shown by girls and boys in their separate playgroups. Researchers have found that in all sorts of relationships, not just marriages, women are on average better than men at attending to and understanding others’ unspoken emotions and needs (Thomas & Fletcher, 2003). Success in marriage may often depend on the husband’s willingness and ability to acquire some of the intimacy skills that he practiced less, as a child, than did his wife.

In their research at the University of Denver, Howard Markman and his colleagues (2004) identified several risk factors for unhappy marriages and divorce. Some of these factors are beyond the individual’s control, such as experiencing serious money problems or having divorced parents. Personality can also play a role; individuals who react defensively to problems and disappointments are at risk. Other risk factors include marrying someone from a different religious background, marrying very young, getting married after knowing each other for only a short time, and having unrealistic beliefs about marriage. Perhaps paradoxically, couples that live together before marriage also have a higher rate of marital conflict and divorce than those who wait until marriage to live together. If a partner has been divorced, this increases the risk of marital difficulties, especially if he or she also has children from the prior marriage.

496

However, Markman and colleagues also identified relationship patterns that can be changed for the better if the couple is willing to work on them. These include:

- Use a positive style of talking and resolving arguments (e.g., avoid putdowns, yelling, and name calling)

- Make an effort to communicate when you disagree (e.g., don’t sulk or give the “silent treatment”)

- Learn to handle disagreements as a team (e.g., capitalize on each other’s strengths to resolve conflicts)

- Be honest with yourself and your partner: Are you completely committed to each other for the long term?

Employment

Work, of course, is first and foremost a means of making a living, but it is more than that. It occupies an enormous portion of adult life. Work can be tedious and mind numbing or exciting and mind building. At its best, work is for adults what play is for children. It brings them into social contact with their peers outside the family, poses interesting problems to solve and challenges to meet, promotes development of physical and intellectual skills, and is fun.

The Value of Occupational Self-Direction

In surveys of workers, people most often say they enjoy their work if it is (a) complex rather than simple, (b) varied rather than routine, and (c) not closely supervised by someone else (Galinsky et al., 1993; Kohn, 1980). Sociologist Melvin Kohn refers to this much-desired constellation of job characteristics as occupational self-direction. A job high in occupational self-direction is one in which the worker makes many choices and decisions throughout the workday. Self-direction is a key characteristic of entrepreneurship (starting ones’ own business) and is also typical of jobs in small businesses, as well as top-level management positions in larger organizations. Research suggests that jobs of this sort, despite their high demands, are for most people less stressful—as measured by effects on workers’ mental and physical health—than are jobs in which workers make few choices and are closely supervised (Spector, 2002). Research also suggests that such jobs promote certain positive personality changes.

35

What evidence suggests that the type of job one has can alter one’s way of thinking and style of parenting and can influence the development of one’s children?

In a massive, long-term study, conducted in both the United States and Poland, Kohn and his colleague Kazimierz Slomczynski found that workers who moved into jobs that were high in self-direction, from jobs that were low in that quality, changed psychologically in certain ways, relative to other workers (Kohn & Slomczynski, 1990). Over their time in the job, they became more intellectually flexible, not just at work but in their approaches to all areas of life. They began to value self-direction more than they had before, in others as well as in themselves. They became less authoritarian and more democratic in their approaches to child rearing; that is, they became less concerned with obedience for its own sake and more concerned with their children’s abilities to make decisions. Kohn and Slomczynski also tested the children. They found that the children of workers in jobs with high self-direction were more self-directed and less conforming than children of workers whose jobs entailed less self-direction. Thus the job apparently affected the psychology not just of the workers but also of the workers’ children.

497

All these effects occurred regardless of the salary level or prestige level of the job. In general, blue-collar jobs were not as high in self-direction as white-collar jobs, but when they were as high, they had the same effects. Kohn and Slomczynski contend that the effects they observed on parenting may be adaptive for people whose social class determines the kinds of jobs available to them. In settings where people must make a living by obeying others, it may be sensible to raise children to obey and not question. In settings where people’s living depends on their own decision making, it makes more sense to raise children to question authority and think independently.

Balancing Out-of-Home and At-Home Work

Women, more often than men, hold two jobs—one outside the home and the other inside. Although men today spend much more time at housework and child care than they did in decades past, the average man is still less involved in these tasks than the average woman (although the gender difference becomes much smaller when home maintenance and repair is included) (Foster & Kreisler, 2012). Moreover, in dual-career families, women typically feel more conflict between the demands of family and those of work than do men (Bagger et al., 2008; McElwain et al., 2005).

36

What difference has been found between husbands’ and wives’ enjoyment of out-of-home and at-home work? How did the researchers explain that difference?

Despite the traditional stereotype of who “belongs” where—or maybe because of it—some research suggests that wives enjoy their out-of-home work more than their at-home work, while the opposite is true for husbands. Reed Larson and his colleagues (1994) asked 55 working-class and middle-class married parents of school-age children to wear pagers as they went about their daily activities. The pagers beeped at random times during the daytime and evening hours, and at each beep the person filled out a form to describe his or her activity and emotional state just prior to the beep. Over the whole set of reports, wives and husbands did not differ in their self-rated happiness, but wives rated themselves happier at work than at home and husbands rated themselves happier at home than at work. These results held even when the specific type of activity reported at work or at home was the same for the two. When men did laundry or vacuumed at home, they said they enjoyed it; when women did the same, they more often said they were bored or angry. Why this difference?

The men’s greater enjoyment of housework could stem simply from the fact that they did it less than their wives, but that explanation doesn’t hold for the women’s greater enjoyment of out-of-home work. Even the wives who worked away from home for as many hours as their husbands did, at comparable jobs, enjoyed that work more than their husbands did. Larson and his colleagues suggest that both differences derived from the men’s and women’s differing perceptions of their choices and obligations. Men enjoyed housework because they didn’t really consider it their responsibility; they did it by choice and as a gallant means of “helping out.” Women did housework because they felt that they had to; if they didn’t do it, nobody else would, and visitors might assume that a dirty house was the woman’s fault. Conversely, the men had a greater sense of obligation, and reduced sense of choice, concerning their out-of-home work. They felt that it was their duty to support their family in this way. Although the wives did not experience more actual on-the-job choice in Kohn’s sense of occupational self-direction than their husbands did, they apparently had a stronger global belief that their out-of-home work was optional. As Larson and his colleagues point out, the results do match a certain traditional stereotype: Men “slave” at work and come home to relax, and women “slave” at home and go out to relax. What’s interesting is that the very same activity can be slaving for one and relaxing for the other, depending apparently on the feeling of obligation or choice.

498

Growing Old

According to current projections of life expectancy, and taking into account the greater longevity of college graduates compared with the rest of the population, the majority of students reading this book will live past the age of 80. How will today’s young adults change as they grow into middle adulthood and, later, into old age?

Some young people fear old age. There is no denying that aging entails loss. We gradually lose our youthful looks and some of our physical strength, agility, sensory acuity, mental quickness, and memory (see Chapter 10). We lose some of our social roles (especially those related to employment) and some of our authority (as people take us less seriously). We lose loved ones who die before we do, and, of course, with the passing of each year we lose a year from our own life span.

Yet, if you ask older adults, old age is not as bad as it seems to the young. In one study, the ratings that younger adults gave for their expected life satisfaction in late adulthood were much lower than the actual life-satisfaction scores obtained from people who had reached old age (Borges & Dutton, 1976). Research studies, using a variety of methods, have revealed that older adults, on average, report greater current enjoyment of life than do middle-aged people, and middle-aged people report greater enjoyment than do young adults (Mroczek, 2001; Sheldon & Kasser, 2001). This finding has been called the “paradox of aging”: Objectively, life looks worse in old age—there are more pains and losses—but subjectively, it feels better. As we age, our priorities and expectations change to match realities, and along with losses there are gains. We become in some ways wiser, mellower, and more able to enjoy the present moment.

A Shift Toward Focus on the Present and the Positive

37

How does the socioemotional selectivity theory account for older adults’ generally high satisfaction with life?

Laura Carstensen (1992; Carstensen & Mikels, 2005) has developed a theory of aging—called the socioemotional selectivity theory—which helps explain why older adults commonly maintain or increase their satisfaction with life despite losses. According to Carstensen, as people grow older—or, more precisely, as they see that they have fewer years left—they become gradually more concerned with enjoying the present and less concerned with activities that function primarily to prepare for the future. Young people are motivated to explore new pathways and meet new people, despite the disruptions and fears associated with the unfamiliar. Such activities provide new skills, information, social contacts, and prestige that may prove useful in the future. But with fewer years left, the balance shifts. The older one is, the less sense it makes to sacrifice present comforts and pleasures for possible future gain. According to Carstensen, this idea helps us understand many of the specific changes observed in older adults.

As people grow older, they devote less attention and energy to casual acquaintances and strangers and more to people with whom they already have close emotional ties (Fung et al., 1999, 2001; Löckenhoff & Carstensen, 2004). Long-married couples grow closer. Husbands and wives become more interested in enjoying each other and less interested in trying to improve, impress, or dominate each other, and satisfaction with marriage becomes greater (Henry et al., 2007; Levenson et al., 1993). Older adults typically show less anger than do younger adults, in response to similar provocations, and become better at preserving valued relationships (Blanchard-Fields, 2007). Ties with children, grandchildren, and long-time friends grow stronger and more valued with age, while broader social networks become less valued and shrink in size. Such changes have been observed not just among older adults but also among younger people whose life expectancy is shortened by AIDS or other terminal illnesses (Carstensen & Fredrickson, 1998).

499

People who continue working into old age typically report that they enjoy their work more than they did when they were younger (Levinson, 1978; Rybash et al., 1995). They become, on average, less concerned with the rat race of advancement and impressing others and more concerned with the day-to-day work itself and the pleasant social relationships associated with it.

Selective Attention to and Memory for the Positive

38

How might selective attention and selective memory contribute to satisfaction in old age?

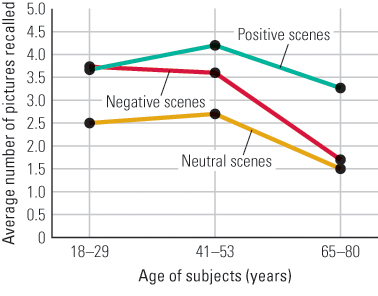

In several experiments, Carstensen and others have shown that older people, unlike younger people, attend more to emotionally positive stimuli than to emotionally negative stimuli and show better memory for the former than the latter (Kisley et al., 2007; Mather & Carstensen, 2003; St. Jacques et al., 2009). In one experiment (Charles et al., 2003), for example, young adults (age 18–29), middle-aged adults (41–53), and old adults (65–80) were shown pictures of positive scenes (such as happy children and puppies), negative scenes (such as a plane crash and garbage), and neutral scenes (such as a runner and a truck). Then they were asked to recall and briefly describe, from memory, as many of the pictures as they could. One predictable result was that older people recalled fewer of the scenes, overall, than did younger people; memory for all information declines as we age. The other, more interesting finding was that the decline in memory with age was much sharper for the negative scenes than for the positive scenes (see Figure 12.12). Apparently, selective attention and memory is one means by which older people regulate their emotions in a positive direction.

This positivity bias extends beyond memory. For instance, older adults are more likely than younger adults to direct their attention away from negative stimuli (Mather & Carstensen, 2003), have greater working memory for positive than for negative emotional images (Mikels et al., 2005), and evaluate events in their own lives more positively than younger adults (Schryer & Ross, 2012). In general, older adults are more emotionally positive than younger adults.

Approaching Death

The one certainty of life is that it ends in death. Surveys have shown that fear of death typically peaks in the person’s fifties, which is when people often begin to see some of their peers dying from such causes as heart attack and cancer (Karp, 1988; Riley, 1970). Older people have less fear of death (Cicirelli, 2001). They are more likely to accept it as inevitable; and death in old age, when a person has lived a full life, seems less unfair than it did earlier.

Various theories have been offered regarding the stages or mental tasks involved in preparing for death. On the basis of her experience with caring for dying patients, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1969) proposed that people go through five stages when they hear that they are incurably ill and will soon die: (1) denial—“The diagnosis can’t be right,” or “I’ll lick it”; (2) anger—“Why me?”; (3) bargaining—“If I do such and such, can I live longer?”; (4) depression—“All is lost”; and (5) acceptance—“I am prepared to die.” Another theory is that preparation for death consists of reviewing one’s life and trying to make sense of it (Butler, 1975).

As useful as such theories may be in understanding individual cases, research shows that there is no universal approach to death. Each person faces it differently. One person may review his or her life; another may not. One person may go through one or several of Kübler-Ross’s stages but not all of them, and others may go through them in a different order (Kastenbaum, 1985). The people whom I (Peter Gray) have seen die all did it in pretty much the way they did other things in life. When my mother discovered that she would soon die—at the too-young age of 62—it was important to her that her four sons be around her so that she could tell us some of the things she had learned about life that we might want to know. She spent her time talking about what, from her present perspective, seemed important and what did not. She reviewed her life, not to justify it but to tell us why some things she did worked out and others didn’t. She had been a teacher all her life, and she died one.

500

SECTION REVIEW

Love and work are the major themes of adulthood.

Love

- Romantic love has much in common with infant attachment to caregivers. The attachment style developed in infancy—secure, anxious, or avoidant—seems to carry forward into adult attachments.

- Happy marriages are generally characterized by mutual liking and respect, individual commitment to the marriage, and constructive means of arguing.

- Wives are generally better than husbands at perceiving and responding to their spouse’s unspoken needs, so marital happiness often depends on the husband’s developing those abilities.

Employment

- Jobs that permit considerable self-direction are enjoyed more than other jobs. Workers with such jobs become more self-directed in their overall approach to Life and may, through their parenting, pass this trait on to their children.

- When husbands and wives both work outside the home, wives generally enjoy the out-of-home work more, and husbands enjoy the at-home work more. Perhaps the nonstereotypical task seems more a matter of choice, which promotes greater enjoyment.

Growing Old

- Older adults generally report greater life satisfaction than do middle-aged and young adults, despite the objective losses that accompany aging.

- Older adults focus more on the present and less on the future than do younger people. They also attend to and remember emotionally positive stimuli more than negative ones.

- Though various theories make general statements about what people do as they approach death, it is really a highly individual matter.