14.3 Effects of Others’ Requests

One of the least subtle yet most potent forms of social influence is the direct request. If the request is small and made politely, we tend to comply automatically (Langer et al., 1978), and this tendency increases when our attention is otherwise occupied (Cialdini, 1993). But even if the request is onerous or offensive, people often find it hard to look a requester in the eye and say no. The tendency to comply usually serves us well. Most requests are reasonable, and we know that in the long run doing things for others pays off, as others in turn do things for us. But from time to time we are faced with situations that threaten to exploit our tendency to comply. It is useful to know the techniques that are often used in such situations so that, instead of succumbing to pressure, we give when we want to give and buy what we want to buy.

Sales Pressure: Some Principles of Compliance

Robert Cialdini (1987, 2001) is a social psychologist who has devoted more than lip service to the idea of combining real-world observations with laboratory studies. To learn about compliance from the real-world experts, he took training in how to sell encyclopedias, automobiles, and insurance; infiltrated advertising agencies and fund-raising organizations; and interviewed recruiters, public-relations specialists, and political lobbyists. He learned their techniques, extracted what seemed to be basic principles, and tested those principles in controlled experiments. The following paragraphs describe a sample of compliance principles taken largely from Cialdini’s work but also much studied by other social psychologists.

Cognitive Dissonance as a Force for Compliance

In Chapter 13 you read about the theory of cognitive dissonance. The basic idea of the theory, as you may recall, is that people are made uncomfortable by contradictions among their beliefs, or between their beliefs and their actions, and their discomfort motivates them to change their beliefs or actions to maintain consistency. According to Cialdini’s analysis, a number of standard sales tricks make use of cognitive dissonance to elicit compliance. Here are two of them.

554

17

How can the low-ball sales technique be explained in terms of cognitive dissonance? What evidence supports this explanation?

Throwing the Low Ball: Increasing the Price After Commitment to Buy One of the most underhanded sales tricks is the low-ball technique. The essence of this technique is that the customer first agrees to buy a product at a low price and then, after a delay, the salesperson “discovers” that the low price isn’t possible and the product must be sold for more. Experiments conducted by Cialdini and others (1978) suggest that the trick works because customers, after agreeing to the initial deal, are motivated to reduce cognitive dissonance by setting aside any lingering doubts they may have about the product. During the delay between the low-ball offer and the real offer, they mentally exaggerate the product’s value; they set their heart on the house, or car, or ice cream treat that they had agreed to purchase. Having done this, they are now primed to pay more than they would have initially.

Consistent with this interpretation, researchers have found that the low-ball technique works only if the customer makes a verbal commitment to the original, low-ball deal (Burger & Cornelius, 2003). If the initial offer is withdrawn and a worse offer is proposed before the person agrees verbally to the initial offer, the result is a reduction in compliance rather than an increase. With no verbal commitment, the customer has no need to reduce dissonance, no need to exaggerate mentally the value of the purchase, and in that case the low-ball offer just makes the final, real offer look bad by comparison.

18

How can the foot-in-the-door sales technique be explained in terms of cognitive dissonance?

Putting a Foot in the Door: Making a Small Request to Prepare the Ground for a Large One With some chagrin, I (Peter Gray) can introduce this topic with a true story in which I was outwitted by a clever gang of driveway sealers. While I was raking leaves in front of my house, these men pulled up in their truck and asked if they could have a drink of water. I, of course, said yes; how could I say no to a request like that? Then they got out of the truck and one said, “Oh, if you have some lemonade or soda, that would be even better; we’d really appreciate that.” Well, all right, I did have some lemonade. As I brought it to them, one of the men pointed to the cracks in my driveway and commented that they had just enough sealing material and time to do my driveway that afternoon, and they could give me a special deal. Normally, I would never have agreed to a bargain like that on the spot; but I found myself unable to say no. I ended up paying far more than I should have, and they did a very poor job. I had been taken in by what I now see to be a novel twist on the foot-in-the-door sales technique.

The basis of the foot-in-the-door technique is that people are more likely to agree to a large request if they have already agreed to a small one (Pascual & Guaguen, 2005). The driveway sealers got me twice on that: Their request for water primed me to agree to their request for lemonade, and their request for lemonade primed me to agree to their offer to seal my driveway. Cialdini (1987) has argued that the foot-in-the-door technique works largely through the principle of cognitive dissonance. Having agreed, apparently of my own free will, to give the men lemonade, I must have justified that action to myself by thinking, These are a pretty good bunch of guys, and that thought was dissonant with any temptation I might have had a few moments later, when they proposed the driveway deal, to think, They may be overcharging me. So I pushed the latter thought out of my mind before it fully registered.

In situations like my encounter with the driveway sealers, the foot-in-the-door technique may work because compliance with the first request induces a sense of trust, commitment, or compassion toward the person making that request. In other situations it may work by inducing a sense of commitment toward a particular product or cause (Burger, 1999). The technique has proved to be especially effective in soliciting donations for political causes and charities. People who first agree to make a small gesture of support, such as by signing a petition or giving a few minutes of their time, are subsequently more willing than they otherwise would be to make a much larger contribution (Cialdini, 2001; Freedman & Fraser, 1966). Apparently the small donation leads the person to develop a firmer sense of support for the cause—”I contributed to it, so I must believe in it”—which in turn promotes willingness to make a larger donation.

555

The Reciprocity Norm as a Force for Compliance

Anthropologists and sociologists have found that people all over the world abide by a reciprocity norm (Gouldner, 1960; Whatley et al., 1999)—that is, people everywhere feel obliged to return favors. This norm is so ingrained that people may even feel driven to reciprocate favors that they didn’t want in the first place. Cialdini (1993) suggests that this is why the technique known as pregiving—such as pinning a flower on the lapel of an unwary stranger before asking for a donation or giving a free bottle of furniture polish to a potential vacuum-cleaner customer—is effective. Having received the gift, the victim finds it hard to turn away without giving something in return.

19

Logically, why should the pregiving and foot-in-the-door techniques be ineffective if combined? What evidence supports this logic?

Notice that pregiving works through a means that is opposite to that proposed for the foot-in-the-door technique. The foot-in-the-door target is first led to make a small contribution, which induces a sense of commitment and thereafter a larger contribution. The reciprocity target, in contrast, is first presented with a gift, which leads to a felt need to give something back. If the two procedures were combined, they should tend to cancel each other out. The contribution would be seen as payment for the gift, reducing any further need to reciprocate, and the gift would be seen as justification for the contribution, reducing cognitive dissonance and thereby reducing the psychological drive to become more committed to the cause.

An experiment involving actual door-to-door solicitation of funds for a local AIDS foundation showed that in fact the two techniques do cancel each other out (Bell et al., 1994). Each person who was solicited first heard the same standard script about the foundation’s good work. Some were then immediately asked for a donation (control condition). Others were given an attractive brochure containing “life-saving information about AIDS” (pregiving condition), or were asked to sign a petition supporting AIDS education (foot-in-the-door condition), or both (combined condition), before they were asked for a donation. As shown in Figure 14.7, the pregiving and foot-in-the-door techniques markedly increased the frequency of giving when either was used alone, but had no effect beyond that of the control condition when the two were combined. This finding not only provides practical information for fund-raisers but also supports the proposed theories about the mechanisms of the two effects. If the two techniques operated simply by increasing the amount of interaction between the solicitor and the person being solicited, then the combined condition should have been most effective.

556

Shared Identity, or Friendship, as a Force for Compliance

20

What evidence suggests that even trivial connections between a sales person and potential customers can increase sales?

Great salespeople are skilled at identifying quickly the things they have in common with potential customers and at developing a sense of friendship or connectedness: “What a coincidence, my Aunt Millie lives in the same town where you were born!” We automatically tend to like and trust people who have something in common with us or with whom we have enjoyed some friendly conversation, and we are inclined to do business with those people. In one series of experiments, compliance to various requests increased greatly when the targets of the requests were led to believe that the requester had the same birthday as they or the same first name or even a similar-looking fingerprint (Burger, 2007; Burger et al., 2004). In other experiments, people were much more likely to comply with a request if they had spent a few minutes sitting quietly in the same room with the requester than if they had never seen that person before (Burger et al., 2001). Apparently, even a brief period of silent exposure makes the person seem familiar and therefore trustworthy.

Conditions That Promote Obedience: Milgram’s Experiments

Obedience refers to those cases of compliance in which the requester is perceived as an authority figure or leader and the request is perceived as an order. Obedience is often a good thing. Obedience to parents and teachers is part of nearly everyone’s social training. Running an army, an orchestra, a hospital, or any enterprise involving large numbers of people would be almost impossible if people did not routinely carry out the instructions given to them by their leaders or bosses. But obedience also has a dark side. Most tragic are the cases in which people obey a leader who is malevolent, unreasonable, or sadly mistaken. Cases in which people, in response to others’ orders, carry out unethical or illegal actions have been referred to as crimes of obedience (Hinrichs, 2007; Kelman & Hamilton, 1989).

Sometimes crimes of obedience occur because the order is backed up by threats; the subordinate’s job or life may be at stake. In other cases, they occur because the subordinate accepts the authority’s cause and doesn’t interpret the action as wrong. In still other cases, however, people follow orders that they believe are wrong, even when there would be no punishment for disobeying. Those are the cases that interest us here because they are the cases that must be understood in terms of psychological pressures. When social psychologists think of such cases, they relate them to a series of experiments performed by Stanley Milgram at Yale University in the early 1960s, which rank among the most famous of all experiments in social psychology. Milgram’s goal was to identify some of the psychological pressures that underlie a person’s willingness to follow a malevolent order.

Milgram’s Basic Procedure and Finding

21

How did Milgram demonstrate that a remarkably high percentage of people would follow a series of orders to hurt another person?

To understand Milgram’s experiments emotionally as well as intellectually, it is useful to imagine yourself as one of his subjects. You enter the laboratory and meet the experimenter and another person, who is introduced to you as a volunteer subject like yourself. The experimenter, a stern and expressionless man, explains that this is a study of the effects of punishment on learning and that one of you will serve as teacher and the other as learner. You draw slips of paper to see who will play which role and find that your slip says “teacher.” The other subject, a pleasant middle-aged man, will be the learner.

557

1993 by Alexandra Milgram, distributed by Alexander Street Press.

You watch while the learner’s arms are strapped to his chair and electrodes are taped to his wrist (see Figure 14.8). The experimenter explains that the straps will prevent excessive movement while the learner is shocked and that the electrode paste on the skin has been applied “to avoid blisters and burns.” While he is being strapped in, the learner expresses some apprehension, saying that he is concerned because he has a heart condition.

After observing this part of the procedure, you—the teacher—are taken to an adjoining room, from which you can communicate with the learner through an intercom. Your job is to read off the questions on a test of verbal memory and to give the learner an electric shock whenever he gives a wrong answer. The shock generator in front of you has 30 switches, labeled with voltage designations from 15 to 450 volts. Additional labels next to the switches describe the shocks as ranging from “Slight shock” to “Danger, severe shock,” followed by two switches labeled “XXX.”

As the experiment progresses, the learner makes frequent mistakes, and at each mistake you give him a stronger shock than you gave before. The learner receives the early shocks silently, but when you get to 75 volts, he responds with an audible “unghh,” and at stronger shocks his protests become more vehement. At 150 volts he cries out, “Experimenter, get me out of here! I won’t be in the experiment any more! I refuse to go on!” At 180 volts he hollers, “I can’t stand the pain!” By 270 volts his response to each shock is an agonized scream, and at 300 volts he shouts in desperation that he will no longer provide answers in the memory test. The experimenter instructs you to continue anyway and to treat each nonresponse as a wrong answer. At 315 and 330 volts the learner screams violently, and then, most frightening of all, from 345 volts on, the learner makes no sound at all. He does not respond to your questions, and he does not react to the shock.

At various points you look to the experimenter and ask if he should check on the learner or if the experiment should be terminated. You might even plead with the experimenter to let you quit giving shocks. At each of these junctures, the experimenter responds firmly with well-rehearsed prompts. First, he says, “Please continue.” If you still protest, he responds, “The experiment requires that you continue.” This is followed, if necessary, by “It is absolutely essential that you continue” and “You have no other choice; you must go on.” These prompts are always used in the sequence given. If you still refuse to go on after the last prompt, the experiment is discontinued.

In reality—as you, serenely reading this book, have probably figured out—the learner receives no shocks. He is a confederate of the experimenter, trained to play his role. But you, as a subject in the experiment, do not know that. You believe that the learner is suffering, and at some point you begin to think that his life may be in danger. What do you do? If you are like the majority of people, you will go on with the experiment to the very end and eventually give the learner the strongest shock on the board—450 volts, “XXX.” In a typical rendition of this experiment, 65 percent (26 out of 40) of the subjects continued to the very end of the series. They did not find this easy to do. Many pleaded with the experimenter to let them stop, and almost all of them showed signs of great tension, such as sweating and nervous tics, yet they went on.

Why didn’t they quit? There was no reason to fear retribution for halting the experiment. The experimenter, although stern, did not look physically aggressive. He did not make any threats. The $5 pay (worth about $50 in today’s money) for participating was so small as to be irrelevant, and all subjects had been told that the $5 was theirs just for showing up. So why didn’t they quit?

558

Explaining the Finding

22

Why does Milgram’s finding call for an explanation in terms of the social situation rather than in terms of unique characteristics of the subjects?

Upon first hearing about the results of Milgram’s experiment, people are tempted to suggest that the volunteers must have been in someway abnormal to give painful, perhaps deadly, shocks to a middle-aged man with a heart condition. But that explanation doesn’t hold up. The experiment was replicated dozens of times, using many different groups of subjects, and yielded essentially the same results each time. Milgram (1974) himself found the same results for women as for men and the same results for college students, professionals, and workers of a wide range of ages and backgrounds. Others repeated the experiment outside the United States, and the consistency from group to group was far more striking than the differences (Miller, 1986). It is tempting to believe that fewer people would obey today than in Milgram’s time, but a recent partial replication casts doubt on that belief (Burger, 2009). In the replication, the experiment stopped, for ethical reasons, right after the 150-volt point for each subject, but nearly as many went to that point as had in Milgram’s original experiments.

Another temptation is to interpret the results as evidence that people in general are sadistic. But nobody who has seen Milgram’s film of subjects actually giving the shocks would conclude that. The subjects showed no pleasure in what they were doing, and they were obviously upset by their belief that the learner was in pain. How, then, can the results be explained? By varying the conditions of the experiment, Milgram (1974) and other social psychologists (Miller, 1986) identified a number of factors that contributed, in these experiments, to the psychological pressure to obey:

23

How might the high rate of obedience in Milgram’s experiments be explained in terms of (a) the norm of obedience, (b) the experimenter’s acceptance of responsibility, (c) the proximity of the experimenter, (d) the lack of a model for rebellion, and (e) the incremental nature of the requests?

- The norm of obedience to legitimate authorities. The volunteer comes to the laboratory as a product of a social world that effectively, and usually for beneficent reasons, trains people to obey legitimate authorities and to play by the rules. Social psychologists refer to this as the norm of obedience (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). An experimenter, especially one at such a reputable institution as Yale University, must surely be a legitimate authority in the context of the laboratory, a context that the subject respects but doesn’t fully understand. Thus, the person enters the laboratory highly prepared to do what the experimenter asks. Consistent with the idea that the perceived legitimacy of the authority contributed to this obedience, Milgram found that when he moved the experiment from Yale to a downtown office building, under the auspices of a fictitious organization, Research Associates of Bridgeport, the percentage who were fully obedient dropped somewhat—from 65 to 48 percent. Presumably, it was easier to doubt the legitimacy of a researcher at this unknown office than that of a social scientist at Yale.

- The experimenter’s self-assurance and acceptance of responsibility. Obedience is predicated on the assumption that the person giving orders is in control and responsible and that your role is essentially that of a cog in a machine. The preexisting beliefs mentioned earlier helped prepare subjects to accept the cog’s role, but the experimenter’s unruffled self-confidence during what seemed to be a time of crisis no doubt helped subjects to continue accepting that role as the experiment progressed. To reassure themselves, they often asked the experimenter questions like “Who is responsible if that man is hurt?” and the experimenter routinely answered that he was responsible for anything that might happen. The importance of attributing responsibility to the experimenter was shown directly in an experiment conducted by another researcher (Tilker, 1970), patterned after Milgram’s. Obedience dropped sharply when subjects were told beforehand that they, the subjects, were responsible for the learner’s well-being.

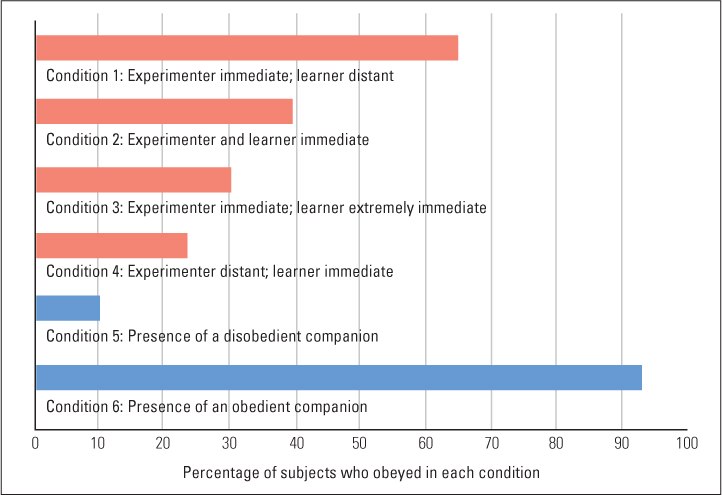

- The proximity of the experimenter and the distance of the learner. We can picture Milgram’s subjects as caught between two conflicting social forces. On one side was the experimenter demanding that the experiment be continued, and on the other was the learner pleading that it be stopped. Not only did the experimenter have the greater initial authority, but he was also physically closer and perceptually more prominent. He was standing in the same room with the subject, while the learner was in another room, out of sight. To test the importance of physical closeness, Milgram (1974) varied the placement of the experimenter or the learner.

559

In one variation, the experimenter left the room when the experiment began and communicated with the subject by telephone, using the same verbal prompts as in the original study; in this case, only 23 percent obeyed to the end, compared with 65 percent in the original condition. In another variation, the experimenter remained in the room with the subject, but the learner was also brought into that room; in this case, 40 percent obeyed to the end. In still another variation, the subject was required to hold the learner’s arm on the shock plate while the shock was administered (see Figure 14.9), with the result that 30 percent obeyed to the end. Thus, any change that moved the experimenter farther away from the subject, or the learner closer to the subject, tended to tip the balance away from obedience.

- The absence of an alternative model of how to behave. Milgram’s subjects were in a novel situation. Unlike the subjects in Asch’s experiments, those in most variations of Milgram’s experiment saw no other subjects who were in the same situation as they, so there were no examples of how to respond to the experimenter’s orders. In two variations, however, a model was provided in the form of another ostensible subject (actually a confederate of the experimenter) who shared with the real subject the task of giving shocks (Milgram, 1974). When the confederate refused to continue at a specific point and the experimenter asked the real subject to take over the whole job, only 10 percent of the real subjects obeyed to the end. When the confederate continued to the end, 93 percent of the real subjects did too. In an unfamiliar and stressful situation, having a model to follow has a potent effect. (For a summary of the results of the variations in Milgram’s experiments, see Figure 14.10.)

- The incremental nature of the requests. At the very beginning of the experiment, Milgram’s subjects had no compelling reason to quit. After all, the first few shocks were very weak, and subjects had no way of knowing how many errors the learner would make or how strong the shocks would become before the experiment ended. Although Milgram did not use the term, we might think of his method as a very effective version of the foot-in-the-door technique. Having complied with earlier, smaller requests (giving weaker shocks), subjects found it hard to refuse new, larger requests (giving stronger shocks). The technique was especially effective in this case because each shock was only a little stronger than the previous one. At no point were subjects asked to do something radically different from what they had already done. To refuse to give the next shock would be to admit that it was probably also wrong to have given the previous shocks—a thought that would be dissonant with subjects’ knowledge that they indeed had given those shocks.

560

Critiques of Milgram’s Experiments

24

How has Milgram’s research been criticized on grounds of ethics and real-world validity, and how has the research been defended?

Because of their dramatic results, Milgram’s experiments immediately attracted much attention and criticism from psychologists and other scholars.

The Ethical Critique Some of Milgram’s critics focused on ethics (Baumrind, 1964). They were disturbed by such statements as this one made in Milgram’s (1963) initial report: “I observed a mature and initially poised businessman enter the laboratory smiling and confident. Within 20 minutes he was reduced to a twitching, stuttering wreck, who was rapidly approaching a point of nervous collapse.” Was the study of sufficient scientific merit to warrant inflicting such stress on subjects, leading some to believe that they might have killed a man?

Milgram took great care to protect his subjects from psychological harm. Before leaving the lab, they were fully informed of the real nature and purpose of the experiment; they were informed that most people in this situation obey the orders to the end; they were reminded of how reluctant they had been to give shocks; and they were reintroduced to the learner, who offered further reassurance that he was fine and felt well disposed toward them. In a survey made a year after their participation, 84 percent of Milgram’s subjects said they were glad to have participated, and fewer than 2 percent said they were sorry (Milgram, 1964). Psychiatric interviews of 40 of the former subjects revealed no evidence of harm (Errera, 1972). Still, because of concern for possible harm, a full replication of Milgram’s experiments would not be approved today by the ethics review boards at any major research institution.

The Question of Generalizability to Real-World Crimes of Obedience Other critics have suggested that Milgram’s results may be unique to the artificial conditions of the laboratory and have little to tell us about crimes of obedience in the real world, such as the Nazi Holocaust (Miller, 2004). Some of these argued that Milgram’s subjects must have known, at some level of their consciousness, that they could not really be hurting the learner because no sane experimenter would allow that to happen (Orne & Holland, 1968). From that perspective, the subjects’ real conflict may have been between the belief that they weren’t hurting the learner and the possibility that they were. Unlike subjects in Milgram’s experiments, Nazis who were gassing people could have had no doubt about the effects of their actions. Another difference is that Milgram’s subjects had no opportunity, outside the stressful situation in which the orders were given, to reflect on what they were doing. In contrast, Nazis who were murdering people would go home at night and then return to the gas chambers and kill more people the next day. Historians have pointed to motives for obedience on the part of Hitler’s followers—including rampant anti-Semitism and nationalism (Goldhagen, 1996; Miller, 2004)—that are unlike any motives that Milgram’s subjects had.

Most social psychologists would agree that Milgram’s findings do not provide full explanations of real-world crimes of obedience, but do shed light on some general principles that apply, in varying degrees, to such crimes. Preexisting beliefs about the legitimacy of the endeavor, the authority’s confident manner, the immediacy of authority figures, the lack of alternative models of how to behave, and the incremental nature of the requests or orders may contribute to real crimes of obedience in much the same way that they contributed to obedience in Milgram’s studies, even when the motives are very different. This may be true for crimes ranging from acts of genocide on down to the illegal “cooking of books” by lower-level corporate executives responding to orders from higher-ups (Hinrichs, 2007).

561

SECTION REVIEW

Our tendency to comply can be exploited by others.

Sales Pressure and Compliance

- Salespersons can manipulate us into making purchases through the low-ball and foot-in-the-door techniques, both of which depend on our tendency to reduce cognitive dissonance.

- Pregiving—such as handing someone a free calendar before requesting a donation—takes advantage of the reciprocity norm, the universal tendency to return favors.

- A sense of having something in common with the salesperson—even something quite trivial—can make us more likely to comply with the sales pitch.

Conditions That Promote Obedience

- In his studies of obedience, Milgram found that most subjects obeyed commands to harm another person, even though it distressed them to do so and there was no real threat or reward involved.

- Factors that help to explain the high rate of obedience in Milgram’s experiments include the prevailing norm of obedience to legitimate authorities, the authority’s acceptance of responsibility, the proximity of the authority figure, the incremental nature of the requests, and the lack of a model for disobeying.

- Though Milgram took precautions to protect his subjects from psychological harm, some critics object to the studies on ethical grounds. Others question whether the results can be generalized to real crimes of obedience, such as the Nazi Holocaust.