16.1 Problems in Identifying Mental Disorders

Human psychological misery comes in an infinite set of shades and intensities. Before clinicians can diagnose a psychological disorder, they must evaluate the behavior in terms of four themes, sometimes referred to as the Four Ds: deviance, distress, dysfunction, and danger. Deviance refers to the degree to which the behaviors a person engages in or their ideas are considered unacceptable or uncommon in society. For example, being convinced you are being controlled by an alien force would be considered deviate in Western society today. Distress refers to the negative feelings a person has because of his or her disorder (for example, persistent sadness), or sometimes by the negative feelings of other people (for example, loss of money due to a spouse’s uncontrolled gambling). Dysfunction refers to the maladaptive behavior that interferes with a person being able to successfully carry out everyday functions, such being able to leave the house or to have social relationships with other people. Finally, danger refers to dangerous or violent behavior directed at other people or oneself (for example, suicidal thoughts, self-mutilation).

618

If you think a bit about the Four Ds you may realize that it is difficult to make a sharp distinction between “abnormal” misery and “normal” misery—that is, between mental disorders and normal, run-of-the-mill psychological disturbances. Yet, mental health professionals regularly do make judgments about the presence or absence of a mental disorder, and they regularly distinguish among and give names to different types of mental disorders. How do they do it?

In an effort to bring consistency to the language used to talk about mental disorders, the American Psychiatric Association has developed a manual, called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, abbreviated DSM. The manual is continuously a work in progress. At the time that we are writing this, its fifth edition, abbreviated DSM-5, has just been published. The manual specifies criteria for deciding what is officially a “disorder” and what it not, and it lists many categories and subcategories of disorders and criteria for identifying them. For better or worse, DSM-5 provides the current standard language for talking about mental disorders, so we use that language in this chapter.

What Is a Mental Disorder?

As we have already implied, mental disorder has no really satisfying definition. It’s a fuzzy concept. Everyone knows that, including the people who wrote DSM-5. Yet, to facilitate communication between and among researchers and clinicians, they had to come up with a definition. For one thing, insurance companies demand that patients be diagnosed as having a mental disorder if there is going to be reimbursement for treatment, so some sort of definition had to be laid out, no matter how fuzzy the concept.

1

How is mental disorder defined by the American Psychiatric Association? What ambiguities lie in that definition?

Let us provide the DSM-5’s definition of a mental disorder:

A mental disorder is a syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning. Mental disorders are usually associated with significant distress in social, occupational, or other important activities. An expectable or culturally approved response to a common stressor or loss, such as the death of a loved one, is not a mental disorder. Socially deviant behavior (e.g., political, religious, or sexual) and conflicts that are primarily between the individual and society are not mental disorders unless the deviance or conflict results from a dysfunction in the individual, as described above. (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 20)

Although this definition provides a useful guideline for thinking about and identifying mental disorders, it is by nature ambiguous, open to a wide range of interpretations; and in some cases it seems to be contradicted by the descriptions of particular disorders in DSM-5 (Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2007).

Just how much distress or dysfunction must a syndrome entail to be considered “clinically significant”? As all behavior involves an interaction between the person and the environment, how can we tell whether the impairment is really within the person, rather than just in the environment? For example, in the case of someone living in poverty or experiencing discrimination, how can we tell if the person’s actions are normal responses to those conditions or represent something more? When people claim that they are deliberately choosing to behave in a way that violates social norms and could behave normally if they wanted to, how do we know when to believe them? A person who starves to protest a government policy may not have a mental disorder, but what about a person who starves to protest the U.S. government’s secret dealings with space aliens who may be planning an invasion? Who has the right to decide whether a person does or does not have a mental disorder: a psychiatrist (a medical doctor specializing in the field of mental disorders) or psychologist—or perhaps a court of law, or a health insurance administrator who must approve or not approve payment for therapy? Or should the decision be made by the person’s family, or the person him- or herself?

619

These are tough questions that can never be answered strictly scientifically. The answers always represent human judgments, and they are always tinged by the social values and pragmatic concerns of those doing the judging.

Categorizing and Diagnosing Mental Disorders

The dividing lines among different mental disorders may be fuzzy, but in order to research and treat such disorders scientists and clinicians need a method for categorizing and labeling them. In keeping with the common Western practice of likening mental disorders to physical diseases, the process of assigning a label to a person’s mental disorder is referred to as diagnosis. To be of value, any system of diagnosis must be reliable and valid.

The Quest for Reliability

The reliability of a diagnostic system refers to the extent to which different diagnosticians, all trained in the use of the system, reach the same conclusion when they independently diagnose the same individuals. If you have ever gone to two different doctors with a physical complaint and been given two different, nonsynonymous labels for your disease, you know that diagnosis is by no means completely reliable, even in the realm of physical disorders. Throughout the first several decades after the discipline of psychology came into being, psychiatrists and clinical psychologists had no reliable, agreed-upon method for diagnosing mental disorders. As a consequence, the same troubled person might be given a diagnosis of schizophrenia by one clinician, depression by another, and neurocognitive disorder by a third.

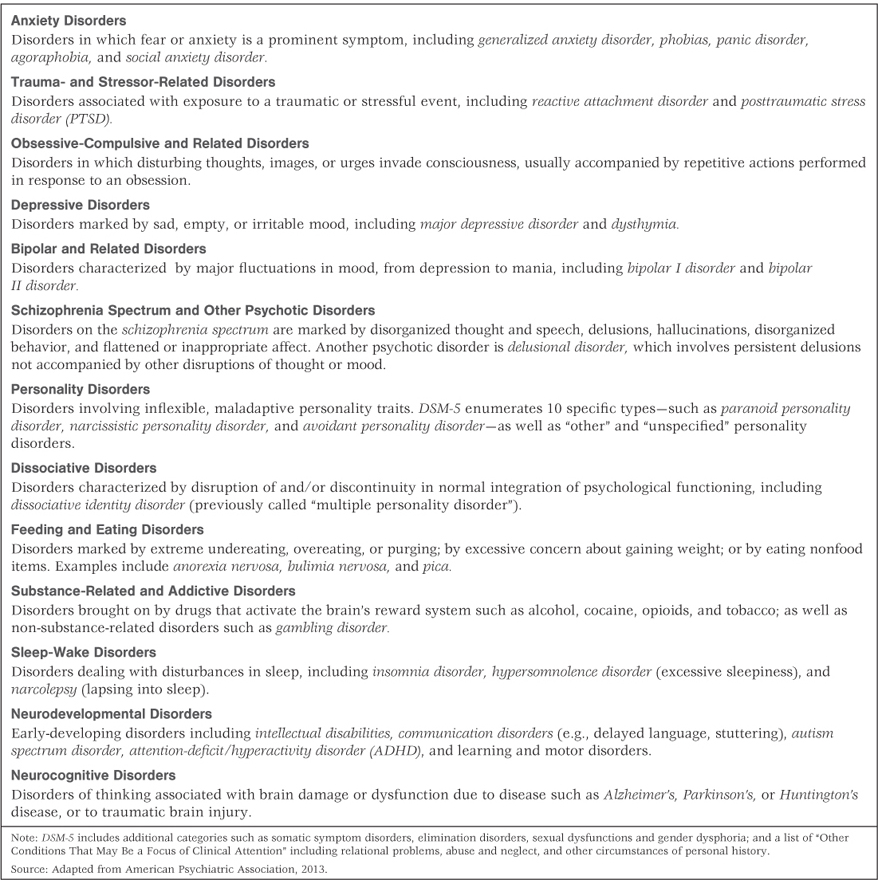

As a step toward remedying this problem, the American Psychiatric Association published the first edition of DSM, in 1952, as a standard system for labeling and diagnosing mental disorders. The DSM was revised in 1968, 1974, 2000, and most recently in 2013, with the goal of defining mental disorders as objectively as possible, in terms of symptoms that clinicians could observe or could assess by asking relatively simple, straightforward questions of the person being diagnosed or of family members or others who knew that person well. To test alternative ways of diagnosing each disorder, they conducted field studies in which people who might have a particular disorder were diagnosed independently by a number of clinicians or researchers using each of several alternative diagnostic systems. In general, the systems that produced the greatest reliability—that is, the greatest agreement among the diagnosticians as to who had or did not have a particular disorder—were retained. The main categories of disorders identified in DSM-5 are listed in Table 16.1. The first seven categories in the list are the ones that we shall discuss in subsequent sections of this chapter.

A sampling of DSM-5 categories of mental disorders

620

As an example of diagnostic criteria specified in DSM-5, consider those for anorexia nervosa, an eating disorder that can result in self-starvation. The person must (a) refuse to maintain body weight at or above a minimally normal weight for age and height; (b) express an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat; (c) manifest a disturbance in the experience of her or his own body weight or shape, show an undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or deny the seriousness of the current low body weight; and (d) if a postpubertal female, have missed at least three successive menstrual periods (a condition brought on by a lack of body fat). If any one of these criteria is not met, a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa would not be made. Notice that all these criteria are based on observable characteristics or self-descriptions by the person being diagnosed; none rely on inferences about underlying causes or unconscious symptoms that could easily result in disagreement among diagnosticians who have different perspectives.

621

The Question of Validity

2

How does validity differ from reliability? How can the validity of the DSM be improved through further research and revisions?

The validity of a diagnostic system is an index of the extent to which the categories it identifies are clinically meaningful. (See Chapter 2, p. 47, for a more general discussion of both validity and reliability.) In theory, a diagnostic system could be highly reliable without being valid. For example, a system that reliably categorizes a group of people as suffering from Disorder X, on the basis of certain superficial characteristics, would not be valid if further work failed to reveal any clinical usefulness in that diagnosis. Do people with the same diagnosis truly suffer in similar ways? Does their suffering stem from similar causes? Does the label help predict the future course of the disorder and help in deciding on a beneficial treatment? To the extent that questions like these can be answered in the affirmative, a diagnostic system is valid.

The question of validity is much more complicated than that of reliability and must be based on extensive research. In order to conduct the research needed to determine whether or not a diagnosis is valid, by the criteria listed earlier, one must first form a tentative, reliable diagnostic system. For example, the DSM-5 definition of anorexia nervosa can be used to identify a group of people whose disorder fits that definition, and then those people can be studied to see if their disorders have similar origins and courses of development and respond similarly to particular forms of treatment. The results of such studies may lead to new means of defining and diagnosing the disorder or to new subcategories of the disorder, leading to increased diagnostic validity.

The DSM is not the only system for classifying mental disorders. The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), which is used in much of the world to classify mental disorders. In addition, questions about the validity of the DSM-5 caused the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the largest source of funding for mental-health research in the United States, to announce plans to develop its own classification system, emphasizing the use of objective laboratory measures, with a focus on biology, genetics, and neuroscience (Insel, 2013). The criticism from the NIMH will not likely end the DSM’s authority, but it does underscore the point that there are vigorous controversies over the identification, definition, and classification of mental disorders, and that perhaps the DSM should be considered less of a Bible for the field of mental health and more of a dictionary.

Possible Dangers in Labeling

3

What are some negative consequences of labeling a person as having a mental disorder? What is recommended as a partial solution to this problem?

Diagnosing and labeling may be essential for the scientific study of mental disorders, but labels can be harmful. A label implying mental disorder has the potential to interfere with the person’s ability to cope with his or her environment through several means: it can stigmatize the person and thereby reduce the esteem accorded to the person by others, it can reduce the labeled person’s own self-esteem, and it may even blind clinicians and others to qualities of the person that are not captured by the label.

To reduce the likelihood of such effects, the American Psychiatric Association (2013) recommends that clinicians apply diagnostic labels only to people’s disorders, not to people themselves. For example, a client or patient might be referred to as a person who has schizophrenia or who suffers from alcoholism but should not be referred to as a schizophrenic or an alcoholic. The distinction might at first seem subtle, but if you think about it, you may agree that it is not so subtle in psychological impact. If we say, “John has schizophrenia,” we tend to be reminded that John is first and foremost a person, with qualities like those of other people, and that his having schizophrenia is just one of many things we could say about him. In contrast, the statement “John is a schizophrenic” tends to imply that everything about him is summed up by that label.

622

As we talk about specific disorders in the remainder of this chapter and the next, we will attempt to follow this advice even though it produces some awkward wording at times. We also urge you to add, in your mind, yet another step of linguistic complexity. When we refer to “a person who has schizophrenia,” you should read this statement as “a person who has been diagnosed by someone as having schizophrenia,” keeping in mind that diagnostic systems are never completely reliable.

Medical Students’ Disease

The power of suggestion, which underlies the ability of labels to cause psychological harm, also underlies what is sometimes called medical students’ disease. This disease, which could also be called introductory psychology students’ disease, is characterized by a strong tendency to relate personally to, and to find in oneself, the symptoms of any disease or disorder described in a textbook. Medical students’ disease was described by the nineteenth-century humorist Jerome K. Jerome (1889/1982) in an essay about his own discomfort upon reading a textbook of medical diagnoses. After explaining his discovery that he must have typhoid fever, St. Vitus’s dance, and a multitude of diseases he had never heard of before, he wrote, “The only malady I concluded I had not got was housemaid’s knee…. I had walked into that reading-room a happy, healthy man. I crawled out a decrepit wreck” (p. 6). As you read about specific disorders later in this chapter, brace yourself against medical students’ disease. Everyone has at least some of the symptoms, to some degree, of essentially every disorder that can be found in this chapter, in DSM-5, or in any other compendium.

Cultural Variations in Disorders and Diagnoses

Mental disorder is, to a considerable degree, a cultural construct. The kinds of distress that people experience, the ways in which they express that distress, and the ways in which other people respond to the distressed person vary from culture to culture and over time in any given culture. Moreover, cultural beliefs and values help determine whether particular syndromes are considered to be disorders or variations of normal behavior.

Culture-Bound Syndromes

The most striking evidence of cross-cultural variation in mental disorders can be found in culture-bound syndromes—expressions of mental distress that are almost completely limited to specific cultural groups (Tseng, 2006). In some cases, such syndromes represent exaggerated forms of behaviors that, in more moderate forms, are admired by the culture

Examples of culture-related syndromes are the eating disorders anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Anorexia nervosa, as noted earlier, is characterized by an extraordinary preoccupation with thinness and a refusal to eat, sometimes to the point of death by starvation. Bulimia nervosa is characterized by periods of extreme binge eating followed by self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives or other drugs, or other means to undo the effects of a binge (at least one binge/one purge per week). It is probably not a coincidence that these disorders began to appear with some frequency in the 1970s in North America and Western Europe, primarily among adolescent girls and young women of the middle and upper classes, and that their prevalence increased through the remainder of the twentieth century (Gordon, 1990; Hoek, 2002). During that period, Western culture became increasingly obsessed with dieting and an ideal of female thinness while, at the same time, weight control became more difficult because of the increased availability of high-calorie foods.

623

Until recently, these eating disorders were almost completely unknown in non-Western cultures. In the early twenty-first century, however, with the increased globalization of Western media and values, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa began to appear throughout the world. Studies in such places as the Pacific Islands and East Africa have shown that the incidence of these disorders correlates directly with the degree of Western media exposure (Becker et al., 2010; Caqueo-Urízar et al., 2011).

An example of a new culturally prepared psychological problem, appearing in various nations, is Internet addiction. This has been most fully documented in South Korea, where frighteningly large numbers of young people are dropping out of school or employment, and some are even starving, because of their compulsive game-playing and other uses of the Internet (Tao et al., 2010). To a lesser degree, Internet addiction appears to be a problem also in the United States, and although it did not find its way into the DSM-5, “Internet gaming disorder” was listed as recommended for further study.

Role of Cultural Values in Determining What Is a Disorder

4

How does the example of homosexuality illustrate the role of culture in determining what is or is not a “disorder”?

Culture does not affect just the types of behaviors and syndromes that people manifest; it also affects clinicians’ decisions about what to label as disorders. A prime example has to do with homosexuality. Until 1973, homosexuality was officially—according to the American Psychiatric Association—a mental disorder in the United States; in that year, the association voted to drop homosexuality from its list of disorders (Minton, 2002). The vote was based partly on research showing that the suffering and impairment associated with homosexuality derived not from the condition itself but from social prejudice directed against homosexuals. The vote was also prompted by an increasingly vocal gay and lesbian community that objected to their sexual orientation being referred to as a disorder, and by gradual changes in attitudes among many in the straight community, who were beginning to accept the normality of homosexuality.

Cultural Values and the Diagnosis of ADHD

The American Psychiatric Association has added many more disorders to DSM over the past three or four decades than it has subtracted. The additions have come partly from increased scientific understanding of mental disorders and partly from a general cultural shift toward seeing mental disorder where people previously saw normal human variation. An example that illustrates both of these trends is attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, which in recent years has been the single most frequently diagnosed disorder among children in the United States (CDC, 2011).

5

How is ADHD identified and treated? How do critics of the high rate of diagnosis of ADHD explain the high rates?

Most diagnoses of ADHD originate because of difficulties in school. Indeed, many of the DSM-5 symptoms of the disorder refer specifically to schoolwork (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The manual describes three varieties of the disorder. The predominantly inattentive type is characterized by lack of attention to instructions, failure to concentrate on schoolwork or other such tasks, and carelessness in completing assignments. The predominantly hyperactive impulsive type is characterized by such behaviors as fidgeting, leaving one’s seat without permission, talking excessively, interrupting others, and blurting out answers before the question is completed. The combined type, which is most common, is characterized by both sets of symptoms.

624

A prominent but still controversial theory of the neural basis of ADHD is that it involves deficits in, or a slower-than-average rate of maturation of, the prefrontal lobes of the cortex—a portion of the brain responsible for focusing attention on tasks and inhibiting spontaneous activities (Barkley, 2001; Shaw et al., 2007). By far the most common treatment is the drug methylphenidate, sold in various short- and long-acting forms under such trade names as Ritalin and Concerta. Methylphenidate increases the activity of the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain, and its effectiveness may derive from its ability to boost neural activity in the prefrontal cortex. This drug reduces the immediate symptoms of ADHD in most diagnosed children, but there are as yet no long-term studies showing that the drug improves children’s lives over the long run, or even for more than 1 year (Konrad et al., 2007). It is also unknown whether it causes long-term negative side effects (LeFever et al., 2003; Singh, 2008).

During the 1990s, the rate of diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in the United States increased eightfold (LeFever et al., 2003). Currently more than 8 percent of all U.S. children and adolescents, age 3 to 17, are diagnosed with the disorder (CDC, 2011; Merikangas et al., 2011). Since boys are diagnosed at rates that are at least three times those of girls, this means that the prevalence of ADHD diagnosis among boys is about 12 percent or more. European Americans, in general, are diagnosed with the disorder more frequently than are African Americans or Latinos, not because they are more disruptive in school but because they are more often referred to clinicians for diagnosis and treatment (LeFever et al., 2003).

Many sociologists and a few psychologists have argued that the explosion in diagnosis of ADHD in the United States and other Western nations derives at least partly from the increased concern about school performance (Rafalovich, 2004), which is manifested in high-stakes standardized testing and competitive admission to magnet schools, advanced-placement programs, and the like. Children everywhere, especially boys, get into trouble in school because of their need for vigorous activity, their impulsiveness, their carelessness about schoolwork, and their willingness to defy teachers and other authority figures. These characteristics vary in a continuous manner, showing the typical bell-shaped distribution of any normal personality dimension (Nigg et al., 2002). Even defenders of the high rate of ADHD diagnosis acknowledge that the characteristics of this disorder exist to some degree in all children, more so in boys than in girls, and that children classed as having the disorder are simply those who have these characteristics to a greater extent than do other children (Maddux et al., 2005; Stevenson et al., 2005). In recent decades, the requirements of schools have become increasingly uniform and have demanded increased levels of docility on the part of children. The ADHD diagnosis and medication of children seems to be the culture’s current preferred way of dealing with the lack of fit between the expectations of schooling and the natural activity level of many children. Consistent with this interpretation is the observation that many, if not most, diagnoses of ADHD originate with teachers’ recommendations (Graham, 2007; Mayes et al., 2009).

Some critics of the high rate of ADHD diagnosis—including a prominent neuroscientist who has conducted research on brain systems involved in this condition (Panksepp, 1998, 2007)—contend that American culture has made it increasingly difficult for children to engage in the sorts of vigorous free play needed by all young mammals, especially young males, for normal development. They contend that, as a culture, we have chosen to treat many children with strong drugs, whose long-term consequences are still unknown, rather than to develop systems of schooling that can accommodate a wider range of personalities and neighborhood spaces that can accommodate children’s needs for rough-and-tumble play.

625

SECTION REVIEW

Mental disorder presents numerous conceptual, diagnostic, and social challenges.

Categorizing and Diagnosing Mental Disorders

- To be considered a mental disorder by DSM-5 standards, a syndrome must be characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning. Though these guidelines are useful, “mental disorder” is still a fuzzy concept.

- Classification and diagnosis (assigning a label to a person’s mental disorder) are essential for clinical purposes and for scientific study of mental disorders.

- The developers of the DSM have increasingly worked on demonstrating reliability (the probability that independent diagnosticians would agree about a person’s diagnosis) by using objective symptoms. Validity is a more complex issue.

- Because labeling a person can have negative consequences (such as lowering self-esteem or the esteem of others), labels should be applied only to the disorder, not to the person.

- Beware of medical students’ disease.

Cultural Variations in Disorders and Diagnoses

- Culture-bound syndromes are expressions of mental distress limited to specific cultural groups. Examples are anorexia and bulimia nervosa (in cultures influenced by modern Western values).

- Culture also affects the types of behaviors or characteristics thought to warrant a diagnosis of mental disorder. Until 1973, homosexuality was officially classed as a mental disorder in the United States.

- The great increase in diagnosis of ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) in the United States may result not just from increased understanding but also from the culture’s increased emphasis on school performance and reduced opportunities for vigorous play.