16.2 Causes of Mental Disorders

Before moving on to discussions of major categories of mental disorders, it is worth spending a little time thinking about the general question of what causes mental disorders. In this section we look first at the brain, which is necessarily involved in all mental disorders. Then we consider a general framework for describing the ways that genes and environment can influence the incidence and onset of mental disorders. And finally we examine some possible reasons why some disorders occur more often in men than in women, or vice versa.

The Brain Is Involved in All Mental Disorders

As has been emphasized throughout this book, all thoughts, emotions, and actions—whether they are adaptive or maladaptive—are products of the brain. All the factors that contribute to the causation of mental disorders do so by acting, in one way or another, on the brain. These include genes that influence brain development; environmental assaults on the brain, such as those produced by a blow to the head, oxygen deprivation, viruses, or bacteria; and, more subtly, the effects of learning, which are consolidated in pathways in the brain.

The Brain’s Role in Irreversible Mental Disorders

The role of the brain is most obvious in certain chronic mental disorders—that is, in certain disorders that stay with a person for life once they appear. In these cases the brain deficits are irreversible—or at least cannot be reversed by any methods yet discovered. One example of such a disorder is autism, or autistic spectrum disorder. Although no definitive cause for autism has been identified, research has found a correlation between autism and a particular brain abnormality that may be caused in some cases primarily by genes and in other cases primarily by prenatal toxins or birth complications that disrupt normal brain development (Kabot et al., 2003). Two other examples are Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. We describe them briefly here because they are disorders linked to obvious brain deficits, for which the causes are reasonably well understood.

626

6

How are Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease characterized as brain diseases?

Down syndrome is a congenital (present at birth) disorder that appears in about 1 out of every 700 newborn babies in the United States (Parker et al., 2010). It is caused by an error in meiosis, which results in an extra chromosome 21 in the egg cell or (less often) the sperm cell (the numbering of chromosomes is depicted in Figure 3.3, p. 61). The extra chromosome is retained in all cells of the newly developing individual. Through a variety of means, it causes damage to many regions of the developing brain, such that the person goes through life with moderate to severe intellectual disability and with difficulties in physical coordination.

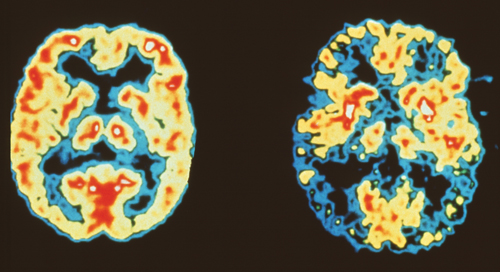

Alzheimer’s disease, found primarily in older adults, has become increasingly prevalent as ever more people live into old age. It occurs in about 1 percent of people who are in their 60s, 3 percent of those in their 70s, 12 percent of those in their 80s, and 40 percent of those in their 90s (Alzheimer’s Association, 2013). The disorder is characterized psychologically by a progressive deterioration, over the final years of the person’s life, in all cognitive abilities—including memory, reasoning, spatial perception, and language—followed by deterioration in the brain’s control of bodily functions.

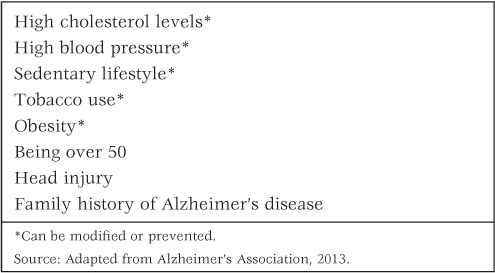

Neurologically, Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by certain physical disruptions in the brain, including the presence of amyloid plaques. The plaques are deposits of a particular protein, called beta amyloid, which form in the spaces between neurons and may disrupt neural communication (Clark et al., 2011; Nicoll et al., 2004). The disorder appears to be caused by a combination of genetic predisposition and the general debilitating effects of old age. Among the genes that may contribute are those that affect the rate of production and breakdown of beta amyloid (Bertram & Tanzi, 2008). Age may contribute partly through the deterioration of blood vessels, which become less effective in carrying excess beta amyloid out of the brain (Nicoll et al., 2004). Although old age is the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, there are others, which are listed in Table 16.2.

Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease

Role of the Brain in Episodic Mental Disorders

Many disorders, including all the disorders discussed in the remaining sections of this chapter, are episodic, meaning that they are reversible. They may come and go, in episodes. Episodes of a disorder may be brought on by stressful environmental experiences, but the predisposition for the disorder nevertheless resides in one way or another in the brain.

627

Most mental disorders, including those that are episodic, are to some degree heritable. The more closely related two people are genetically, the more likely it is that they share the same mental disorder or disorders, regardless of whether or not they were raised in the same home (Howland, 2005; Rutter, 2006). In most cases it is not known just which genes are involved or how they influence the likelihood of developing the disorder, but it is reasonable to assume that such effects occur primarily through the genes’ roles in altering the biology of the brain. Environmental assaults to the brain and the effects of learning can also contribute to the predisposition for episodic disorders.

A Framework for Thinking About Multiple Causes of Mental Disorders

7

How can the causes of mental disorders be categorized into three types—“the three Ps”?

Most mental disorders derive from the joint effects of more than one cause. Most disorders are not present at birth, but first appear at some point later in life, often in early adulthood. The subsequent course of a disorder—its persistence, its severity, its going and coming—is influenced by experiences that one has after the disorder first appears. It is useful, therefore, to distinguish among three categories of causes of mental disorders: predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating causes—the three Ps.

Predisposing causes of mental disorders are those that were in place well before the onset of the disorder and make the person susceptible to the disorder. Genetically inherited characteristics that affect the brain are most often mentioned in this category. Predispositions for mental disorders can also arise from damaging environmental effects on the brain, including effects that occur before or during birth. Such environmental assaults as poisons (including alcohol or other drugs consumed by the mother during pregnancy), birth difficulties (such as oxygen deprivation during birth), and viruses or bacteria that attack the brain can predispose a child for the subsequent development of one or more mental disorders.

Prolonged psychologically distressing situations—such as living with abusive parents or an abusive spouse—can also predispose a person for one or another mental disorder. Other predisposing causes include certain types of learned beliefs and maladaptive patterns of reacting to or thinking about stressful situations. A young woman reared in upper-class Western society is more likely to acquire beliefs and values that predispose her for an eating disorder than is a young woman from a rural community in China. Highly pessimistic habits of thought, in which one regularly anticipates the worst and fails to think about reasons for hope, predispose people for mood disorders (particularly depression) and anxiety disorders.

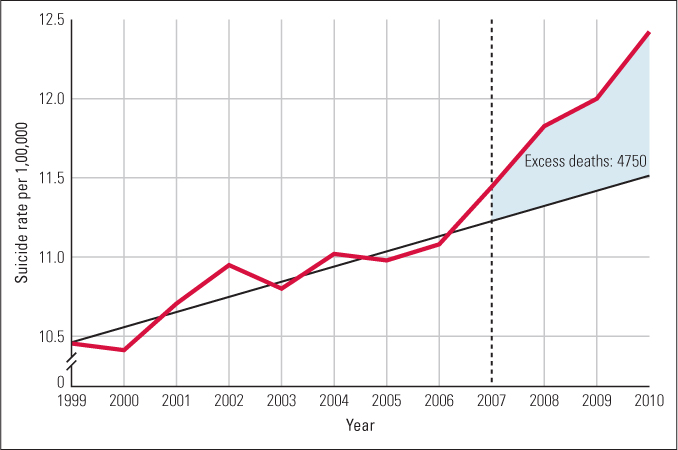

Precipitating causes are the immediate events in a person’s life that bring on the disorder. Any loss, such as the death of a loved one or the loss of a job; any real or perceived threat to one’s well-being, such as physical disease; any new responsibility, such as might occur as a result of marriage or job promotion; or any large change in the day-to-day course of life can, in the sufficiently predisposed person, bring on the mood or behavioral change that leads to diagnosis of a mental disorder. Figure 16.1 shows how the recent economic recession served as a precipitating event for an increase in suicides in the United States.

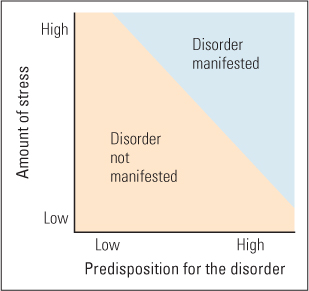

Precipitating causes are often talked about under the rubric of stress, a term that sometimes refers to the life event itself and sometimes to the worry, anxiety, hopelessness, or other negative experiences that accompany the life event (Lazarus, 1993). When the predisposition is very high, an event that seems trivial to others can be sufficiently stressful to bring on a mental disorder. When the predisposition is very low, even an extraordinarily high degree of loss, threat, or change may fail to bring on a mental disorder. Figure 16.2 depicts this inverse relationship.

628

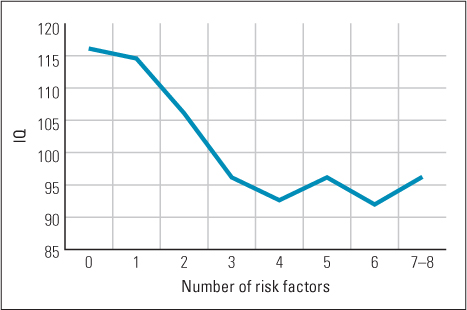

When looking at early environments as precipitating causes, the standard assumption is that positive environments—those that provide adequate resources and social and emotional support—produce “good” developmental outcomes such as educational success, emotional regulation, and mental health, whereas negative environments—characterized by high levels of stress and inadequate emotional and social support—produce “bad” developmental outcomes such as poor performance in school, poor self-regulation, and mental illness. The negative effects of an adverse environment are proposed to be especially harmful if an individual has a biological predisposition to respond especially strongly to stress. Essentially, early negative experience disturbs the typical course of development, leading to maladaptive behavior and poor mental health. The more risk factors an individual experiences, the greater the deficits in functional behavior (see Figure 16.3).

Although there is much research to support this contention (Cicchetti & Blender, 2004; Evans, 2003; Sameroff et al., 1993), it ignores the fact that, from an evolutionary developmental perspective, humans evolved to respond to different environmental contexts—good and bad—in an adaptive manner, and that some of the dysfunctional outcomes observed when some children grow up in high-stress environments may reflect their development being directed or regulated toward acquiring adaptive strategies to cope in these stressful environment (Ellis et al., 2012). For example, Jeffrey Simpson and his colleagues (2012) reported that children whose first 5 years of life could be described as highly unpredictable (for example, changes in residences, parental job changes, different adult males living in the household), had their first sexual intercourse sooner, more sex partners, and higher levels of aggression, risk-taking, and delinquent behaviors at 23 years of age than children growing up in more predictable homes. Although these are all signs of maladjustment in modern society, they reflect what has been called a “fast life history strategy,” in which people engage in more risky behaviors, which is adaptive (or would have been adaptive for our ancestors) in uncertain and stressful environments (Ellis et al., 2009).

Perpetuating causes are those consequences of a disorder that help keep it going once it begins. In some cases, a person who behaves maladaptively may gain rewards, such as extra attention, which helps perpetuate the behavior. More often, the negative consequences of the disorder help perpetuate it. For example, a sufferer of depression may withdraw from friends, and lack of friends can perpetuate the depression. Behavioral changes brought on by a disorder, such as poor diet, irregular sleep, and lack of exercise, may also contribute to prolonging the disorder. Expectations associated with a particular disorder may play a perpetuating role as well. In a culture that regards a particular disorder as incurable, a person diagnosed with that disorder may simply give up trying to change for the better.

629

Possible Causes of Sex Differences in the Prevalence of Specific Disorders

Little difference occurs between men and women in the prevalence of mental disorder when all disorders are combined, but large differences are found for specific disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Women are diagnosed with anxiety disorders and depression at rates that are nearly twice as great as those for men. Men are diagnosed with intermittent explosive disorder (characterized by relatively unprovoked violent outbursts of anger) and with antisocial personality disorder (characterized by a history of antisocial [harmful to others] acts with no sense of guilt) at rates that are three or four times those for women. Men are also diagnosed with substance-use disorders (including alcohol dependence and other drug dependence) at rates that are nearly twice as great as those for women. These sex differences may arise from a number of causes, including the following:

8

What are four possible ways of explaining sex differences in the prevalence of specific mental disorders?

© Stockbroker/MBI/Alamy

- Differences in reporting or suppressing psychological distress. Diagnoses of anxiety disorders and of depression necessarily depend to a great extent on self-reporting. Men, who are supposed to be the “stronger” sex, may be less inclined than women to admit to anxiety and despondency in interviews or questionnaires. Supporting this view, experiments have shown that when men and women are subjected to the same stressful situation, such as a school examination, men report less anxiety than do women even though they show physiological signs of distress that are as great as, or greater than, those shown by women (Polefrone & Manuck, 1987).

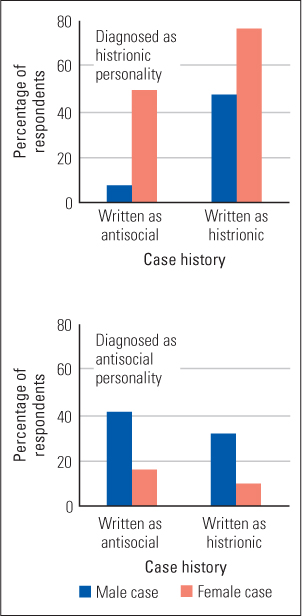

- Clinicians’ expectations. Diagnosticians may, to some degree, find a disorder more often in one sex than in the other because they expect to find it. In an experiment demonstrating such an expectancy bias, several hundred clinical psychologists in the United States were asked to make diagnoses on the bases of written case histories that were mailed to them (Ford & Widiger, 1989). For some, the case history was constructed to resemble the DSM-III criteria for antisocial personality disorder (characterized by disregard or violation of the rights of others; discussed later in the chapter), which is diagnosed more often in men than in women. For others it was constructed to resemble the DSM-III criteria for histrionic personality disorder (characterized by dramatic expressions of emotion to seek attention; discussed later in the chapter), which is diagnosed more often in women. Each of these case histories was written in duplicate forms, for different clinicians, differing only in the sex of the person being described. As you can see in Figure 16.4, the diagnoses were strongly affected by the supposed patient’s sex. Given the exact same case histories, the man was far more likely than the woman to receive a diagnosis of antisocial personality, and the woman was far more likely than the man to receive a diagnosis of histrionic personality.

Figure 16.4 Evidence of a gender bias in diagnosis In this study, case histories were more likely to be diagnosed as antisocial personality if they described a fictitious male patient and as histrionic personality if they described a fictitious female patient, regardless of which disorder the case history was designed to portray.(Based on data from Ford & Widiger, 1989.)

Figure 16.4 Evidence of a gender bias in diagnosis In this study, case histories were more likely to be diagnosed as antisocial personality if they described a fictitious male patient and as histrionic personality if they described a fictitious female patient, regardless of which disorder the case history was designed to portray.(Based on data from Ford & Widiger, 1989.) - Differences in stressful experiences. A number of well-controlled studies indicate that at least some sex differences in the prevalence of disorders are real—they cannot be explained by sex differences in reporting or by biased diagnoses (Klose & Jacobi, 2004). One way to explain such actual differences is to search for differences in the social experiences of men and women. Throughout the world, women are more likely than men to live in poverty, to experience discrimination, to have been sexually abused in childhood, and to be physically abused by their spouses—all of which can contribute to depression, anxiety, and various other disorders that occur more often in women than in men (Koss, 1990; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001; Olff et al., 2007). There is also evidence that the typical responsibilities that women assume in the family, such as caring for children, are more conducive to anxiety and depression than are the typical roles that men assume (Almeida & Kessler, 1998; Barnett & Baruch, 1987).

- Differences in ways of responding to stressful situations. The two sexes not only tend to experience different sorts of stressful situations, but also tend to respond differently to objectively similar situations (Kramer et al., 2008). Women tend to “internalize” their discomfort; they dwell mentally (ruminate) on their distress and seek causes within themselves. This manner of responding, in either sex, tends to promote both anxiety and depression (Kramer et al., 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001). Men, in contrast, more often “externalize” their discomfort; they tend to look for causes outside of themselves and to try to control those causes, sometimes in ways that involve aggression or violence. It is not clear what causes these differences in ways of responding, but it is reasonable to suppose that they are, in part, biologically predisposed. Such differences are observed throughout the world, and there is evidence that male and female hormones influence the typically male and female ways of reacting to stressful situations (Olff et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2000).

SECTION REVIEW

Though mental disorders have many possible causes, all exert their effects via the brain.

The Brain’s Role in Chronic and Episodic Mental Disorders

- Chronic mental disorders such as Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease arise from irreversible brain deficits.

- Down syndrome derives from an extra chromosome 21, and Alzheimer’s disease is correlated with disruptive effects of amyloid plaques in the brain.

- All the other disorders discussed in the chapter are episodic. Causes may include hereditary influences on the brain’s biology, environmental assaults on the brain, and effects of learning.

A Framework for Thinking About Multiple Causes

- Predisposing causes include genetic influences, early environmental effects on the brain, and learned beliefs.

- Precipitating causes are generally stressful life experiences or losses.

- Perpetuating causes include poor self-care, social withdrawal, and negative reactions from others.

Causes of Sex Differences in Prevalence of Specific Disorders

- Some diagnoses are much more prevalent in women, and some others are much more prevalent in men.

- Such differences may derive from (a) sex differences in the tendency to report or suppress psychological distress; (b) clinicians’ expectations of seeing certain disorders more often in one sex than in the other; (c) sex differences in stress associated with differing social roles; or (d) sex differences in ways of responding to stress.

631