16.3 Anxiety Disorders

The rabbit crouches, frozen in the grass, minimizing its chance of being detected. Its sensory systems are at maximum alertness, all attuned to the approaching dog. With muscles tense, the rabbit is poised to leap away at the first sign that it has been detected; its heart races, and its adrenal glands secrete hormones that help prepare the body for extended flight if necessary. Here we see fear operating adaptively, as it was designed to operate by natural selection.

We humans differ from the rabbit on two counts: Our biological evolution added a massive, thinking cerebral cortex atop the more primitive structures that organize fear, and our cultural evolution led us to develop a habitat far different from that of our ancestors. Our pattern of fear is not unlike the rabbit’s, but it can be triggered by an enormously greater variety of both real and imagined stimuli, and in many cases the fear is not adaptive. Fear is not adaptive when it causes a job candidate to freeze during an interview, or overwhelms a student’s mind during an examination, or constricts the life of a person who can vividly imagine the worst possible consequence of every action.

Anxiety disorders are those in which fear or anxiety is the most prominent disturbance. The major anxiety disorders recognized by DSM-5 are generalized anxiety disorder, phobias, and panic disorder. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder had been classified as anxiety disorders in the DSM-IV, but were reclassified in the DSM-5. Nevertheless, because some of the symptoms of these two disorders are similar to those of anxiety disorders, we discuss them in this section. Genetic differences play a considerable role in the predisposition for all these disorders. Research with twins indicates that roughly 30 to 50 percent of the individual variability in risk to develop any given anxiety disorder derives from genetic variability (Gelernter & Stein, 2009; Gordon & Hen, 2004). In what follows, we will describe the main diagnostic characteristics and precipitating causes of each of these common types of anxiety disorders.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Generalized anxiety is called generalized because it is not focused on any one specific threat; instead, it attaches itself to various threats, real or imagined. It manifests itself primarily as worry (Turk & Mennin, 2011). Sufferers of generalized anxiety disorder worry more or less continuously, about multiple issues, and they experience muscle tension, irritability, and difficulty in sleeping. They worry about the same kinds of issues that most of us worry about—family members, money, work, illness, daily hassles—but to a far greater extent and with much less provocation (Becker et al., 2003).

To receive a DSM-5 diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, such life-disrupting worry must occur on more days than not for at least 6 months and occur independently of other diagnosable mental disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Roughly 6 percent of people in North America could be diagnosed as having this disorder at some time in their lives (Kessler et al., 2005). In predisposed people, the disorder often first appears at a diagnosable level following a major life change in adulthood, such as getting a new job or having a baby; or after a disturbing event, such as a serious accident or illness (Blazer et al., 1987).

632

9

How can generalized anxiety disorder be understood in terms of hypervigilance, genes, early traumatic experiences, and cultural conditions?

Laboratory research shows that people diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder are particularly attuned to threatening stimuli. For example, they notice threatening words (such as “cancer” or “collapse”) more quickly, reliably, and automatically than do other people, whereas they show no such differences in recognition of nonthreatening words (Mogg & Bradley, 2005). Such automatic attention to potential threat is referred to as hypervigilance, and there is evidence that such vigilance begins early in life and precedes the development of generalized anxiety disorder (Eysenck, 1992). Thus, hypervigilance may be a predisposing cause of generalized anxiety disorder as well as a symptom of the disorder.

Hypervigilance may result, in part, from genetic influences on brain development. As noted in Chapter 6, the brain’s amygdala responds automatically to fearful stimuli, even when those stimuli don’t reach the level of conscious awareness. In most of us, connections from the prefrontal lobe of the cortex help to control the fear reactions, but neuroimaging studies suggest that these inhibitory connections are less effective in people who are predisposed for generalized anxiety (Bishop, 2009). A lifelong tendency toward hypervigilance is also found in many individuals who experienced unpredictable traumatic experiences in early childhood (Borkovec et al., 2004). In an environment where dangerous things can happen at any time, a high degree of vigilance is adaptive.

Surveys taken at various times, using comparable measures, indicate that the average level of generalized anxiety in Western cultures has increased sharply since the middle of the twentieth century (Twenge, 2000). From a cultural perspective, that increase may be attributable to the reduced stability of the typical person’s life. In a world of rapid technological change, we can’t be sure that today’s job skills will still be useful tomorrow. In a world of frequent divorce and high mobility, we can’t be sure that the people we are attached to now will be “there for us” in the future. In a world of rapidly changing values and expectations, we have difficulty judging right from wrong or safe from unsafe. Such threats may be felt only dimly and lead not to conscious articulation of specific fears but to generalized anxiety. And, unlike the predator that scares the rabbit one minute and is gone the next, these threats are with us always.

Phobias

In contrast to generalized anxiety, a phobia is an intense, irrational fear that is very clearly related to a particular category of object or event. The fear is of some specific, nonsocial category of object or situation. It may be of a particular type of animal (such as snakes), substance (such as blood), or situation (such as heights or being closed in). For a diagnosis to be given, the fear must be long-standing and sufficiently strong to disrupt everyday life in some way—such as causing one to leave a job or to refrain from leaving home in order to avoid encountering the feared object. Phobias are quite prevalent; surveys suggest that they are diagnosable, at some time in life, in somewhere between 7 and 13 percent of people in Western societies (Hofmann et al., 2009; Kessler et al., 2005).

Usually a phobia sufferer is aware that his or her fear is irrational but still cannot control it. The person knows well that the neighbor’s kitten won’t claw anyone to death, that common garter snakes aren’t venomous, or that the crowd of 10-year-olds at the corner won’t attack. People with phobias suffer doubly—from the fear itself and from knowing how irrational they are to have such a fear (Williams, 2005). Laboratory research shows that people with phobias are hypervigilant specifically for the category of object that they fear. For example, people with spider phobias can find spiders in photographs that contain many objects more quickly than can other people. Once they have spotted the object, however, they avert their eyes from it more quickly than do other people (Pflugshaupt et al., 2005).

633

The Relation of Phobias to Normal Fears

Probably everyone has some irrational fears, and, as in all other anxiety disorders, the difference between the normal condition and the disorder is one of degree, not kind. Phobias are usually of things that many people fear to some extent, such as snakes, spiders, blood, darkness, or heights (Marks, 1987); and social phobias may simply be extreme forms of shyness (Rapee & Spence, 2004).

Also consistent with the idea that phobias lie on a continuum with normal fears is the observation that phobias are much more often diagnosed in women than in men (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In the population as a whole, men and boys are much less likely than women and girls to report fears of such things as spiders and darkness. The sex difference in phobias could stem from the fact that boys are more strongly encouraged than are girls to overcome or to hide their childhood fears (Fodor, 1982).

Phobias Explained in Terms of Evolution and Learning

10

How might phobias be explained in terms of learning that has been prepared by evolution?

Relatively little is known about how phobias usually arise, but learning certainly plays some role in many, if not most, cases (Mineka & Zinbarg, 2006). Approximately 40 percent of people with phobias recall some specific traumatic situation in which they first acquired the fear (Hofmann et al., 2009). For example, people with dog phobias often recall an experience of being severely bitten by a dog. As described in Chapter 4, such experiences may be understood in terms of classical conditioning: The dog, in the example, is the conditioned stimulus for fear, and the bite is the unconditioned stimulus. After the conditioning experience, the dog elicits fear even without a bite. In such trauma-producing situations, just one pairing of conditioned and unconditioned stimuli may be sufficient for strong conditioning to occur.

Contrary to a straightforward learning theory of phobias, however, is the observation that people often develop phobias of objects that have never inflicted damage or been a true threat to them. For example, a survey conducted many years ago in Burlington, Vermont, where there are no dangerous snakes, revealed that the single most common phobia there was of snakes (Agras et al., 1969). If phobias are acquired through traumatic experiences with the feared object, then why aren’t phobias of such things as automobiles, electric outlets, or (in Vermont) icy sidewalks more common than phobias of harmless snakes?

11

Are phobias such as fear of snakes “innate”? Can an evolutionary perspective help us explain some phobias?

According to an evolutionary account of phobias, first proposed by Martin Seligman (1971), people are genetically prepared to be wary of—and to learn easily to fear—objects and situations that would have posed realistic dangers during most of our evolutionary history. This idea is helpful in understanding why phobias of snakes, spiders, darkness, and heights are more common than those of automobiles and electric outlets. Research has shown that people can acquire strong fears of such evolutionarily significant objects and situations more easily than they can acquire fears of other sorts of objects (Mineka & Zinbarg, 2006). Simply observing others respond fearfully to them, or reading or hearing fearful stories about them, can initiate or contribute to a phobia.

With respect to snakes, anyway, young children, although not innately fearful of snakes, more easily associate them with fearful responses than other animals. In one study, 7- to 9-month-old infants and 14- to 16-month-old toddlers watched videos of snakes and other animals (giraffes, rhinoceroses) and heard either a fearful or happy voice associated with each animal (DeLoache & LoBue, 2009). Although the children showed no fear of snakes when first watching the video, they looked longer at the snakes when they heard the fearful voice than when they heard the happy voice. There was no difference in their looking times to the two voices when they watched videos of other animals. These findings, along with others showing that monkeys more readily react fearfully after watching another monkey respond with freight to a snake than to a rabbit or a flower (Cook & Mineka, 1989), suggest that infants are prepared to acquire a fear of snakes. Neither children nor monkeys are born with this fear, but rather they seem to possess perceptual biases to attend to certain types of stimuli and to associate them with fearful voices or reactions. In some people, such fears can develop into phobias.

634

The fact that some people acquire phobias and others don’t in the face of similar experiences probably stems from a variety of predisposing factors, including genetic temperament and prior experiences (Craske, 1999). Suppose you have had a great deal of safe, prior experience with a type of object, such as snakes. In that case, if you are unfortunate enough to have a traumatic encounter with a snake, you are less likely to develop a snake phobia than are people whose first exposure to snakes was traumatic (Field, 2006). As discussed in Chapter 4, classical conditioning of fears is reduced or blocked if the conditioned stimulus is first presented many times in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus.

People with phobias have a strong tendency to avoid looking at or being anywhere near the objects they fear, and this behavior pattern tends to perpetuate the disorder. To understand why this is so, recall from Chapter 4 that operant conditioning occurs through reinforcement following a behavior. When confronted with the feared object, even in the form of a photograph or television show, the person experiences anxiety. By avoiding the object, the person experiences the negative reinforcement of reduced anxiety (“Ah! I feel better now!”) and thereby learns to avoid (for example) snakes, instead of learning that snakes found in Vermont are harmless. Without exposure to snakes, there is little opportunity to overcome a fear of them.

Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia

Panic is a feeling of helpless terror, such as one might experience if cornered by a predator. In some people, this sense of terror comes at unpredictable times, unprovoked by any specific threat in the environment. Because the panic is unrelated to any specific situation or thought, the panic victim, unlike the victim of a phobia or an obsessive compulsion, cannot avoid it by avoiding certain situations or relieve it by engaging in certain rituals. Panic attacks usually last several minutes and are accompanied by high physiological arousal (including rapid heart rate and shortness of breath) and a fear of losing control and behaving in some frantic, desperate way (Barlow, 2002). People who have suffered such attacks often describe them as the worst experiences they have ever had—worse than the most severe physical pain they have felt.

To be diagnosed with panic disorder, by DSM-5 criteria, a person must have experienced recurrent unexpected attacks, at least one of which is followed by at least 1 month of debilitating worry about having another attack or by life-constraining changes in behavior (such as quitting a job or refusing to travel) motivated by fear of another attack (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). By these criteria, roughly 2 percent of North Americans suffer from panic disorder at some time in their lives (Kessler et al., 2005).

12

What learned pattern of thought might be a perpetuating cause of panic disorder?

As is true with all other anxiety disorders, panic disorder often manifests itself shortly after some stressful event or life change (White & Barlow, 2002). Panic victims seem to be particularly attuned to, and afraid of, physiological changes that are similar to those involved in fearful arousal. In the laboratory or clinic, panic attacks can be brought on in people with the disorder by any of various procedures that increase heart rate and breathing rate—such as lactic acid injection, a high dose of caffeine, carbon dioxide inhalation, or intense physical exercise (Barlow, 2002). This has led to the view that a perpetuating cause, and possibly also predisposing cause, of the disorder is a learned tendency to interpret physiological arousal as catastrophic (Woody & Nosen, 2009). One treatment, used by cognitive therapists, is to help the person learn to interpret each attack as a temporary physiological condition rather than as a sign of mental derangement or impending doom.

635

Agoraphobia is a fear of public places. People with agoraphobia are commonly afraid that they will be trapped or unable to obtain help in a public setting. Agoraphobia develops at least partly because of the embarrassment and humiliation that might follow loss of control (panic) in front of others (Craske, 1999).

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

13

How does PTSD differ from other anxiety disorders?

Prior to the DSM-5, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was classified as an anxiety disorder. In DSM-5, however, it is classified under Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders. PTSD is necessarily brought on by stressful experiences. By definition, the symptoms of PTSD must be linked to one or more emotionally traumatic incidents that the affected person has experienced. The disorder is most common in torture victims, concentration camp survivors, people who have been raped or in other ways violently assaulted, soldiers who have experienced the horrors of battle, and, most commonly, people who have survived dreadful accidents, including car accidents.

PTSD is characterized by three major symptoms: uncontrollable re-experiencing, heightened arousal, and avoidance of trauma-related stimuli. Re-experiencing of the traumatic event often involves nightmares, “flashbacks” when awake, and distress when reminded about the traumatic event. The second set of symptoms, heightened arousal, involves sleeplessness, irritability, exaggerated startle responses, and difficulty concentrating. Finally, sufferers of PTSD attempt to actively avoid thoughts and situations that remind them of the trauma and often experience emotional numbing and social withdrawal (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Not surprisingly, the prevalence of this disorder depends very much on the population sampled. In the United States, approximately 60 percent of men and 50 percent women experience a least one traumatic event in their lives. Of these, about 8 percent of men and 20 percent of women will develop PTSD (National Center for PTSD, 2010). In contrast, in Algeria, where nearly everyone has been a victim of terrorist attacks, 40 percent of a random sample of adults were found to suffer from this disorder (Khaled, 2004). Similarly, rates of PTSD ranging from 15 to 30 percent have been found in war-torn regions of Cambodia, Ethiopia, and Palestine (de Jong et al., 2003).

PTSD is especially common in soldiers returning from war. The National Center for PTSD (2010) estimates that PTSD affects 10 percent of Gulf War veterans, 11 to 20 percent of Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans, and 30 percent of Vietnam War veterans. Moreover, the problems of veterans with PTSD are often compounded by other behaviors and conditions. Relative to other veterans, veterans with PTSD are more likely to abuse alcohol and other substances (Jacobsen et al., 2001; Tanielian & Jaycox, 2008), to be involved in domestic violence (Tanielian & Jaycox, 2008), and to experience depression and other anxiety disorders (Foa et al., 2013).

14

What conditions are particularly conducive to development of PTSD?

People who are exposed repeatedly, or over long periods of time, to distressing conditions are much more likely to develop PTSD than are those exposed to a single, short-term, highly traumatic incident. One study revealed that the incidence of PTSD among Vietnam War veterans correlated more strongly with long-term exposure to the daily stressors and dangers of the war—such as heat, insects, loss of sleep, sight of dead bodies, and risk of capture by the enemy—than with exposure to a single atrocity (King et al., 1995). Another study, of 3,000 war refugees, revealed that the percentage with PTSD rose in direct proportion to the number of traumatic events they had experienced (Neuner et al., 2004). Likewise, children exposed to repeated abuse in their homes are particularly prone to the disorder (Roesler & McKenzie, 1994). Most people can rebound reasonably well from a single horrific event, but the repeated experience of such events seems to wear that resilience down, perhaps partly through long-term debilitating effects of stress hormones on the brain (Kolassa & Elbert, 2007).

636

Not everyone exposed to repeated highly stressful conditions develops PTSD. Social support, both before and after the stressful experiences, seems to play a role in reducing the likelihood of the disorder (Ozer et al., 2003). Genes also play a role (Paris, 2000). One line of evidence for that comes from a study of twins who fought in Vietnam. Identical twins were considerably more similar to each other in the incidence of the disorder and in the types of symptoms they developed than were fraternal twins (True et al., 1993).

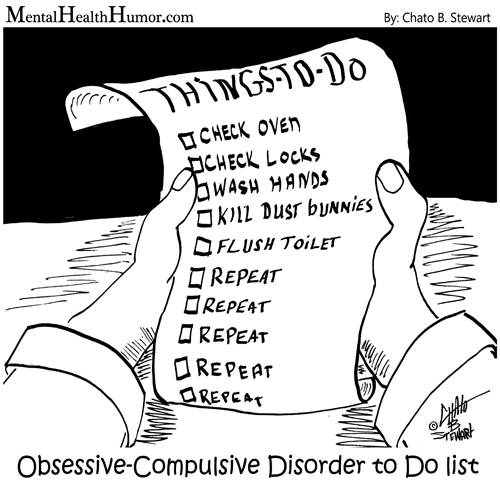

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

An obsession is a disturbing thought that intrudes repeatedly on a person’s consciousness even though the person recognizes it as irrational. A compulsion is a repetitive action that is usually performed in response to an obsession. Most people experience moderate forms of these, especially in childhood (Mathews, 2009). I (Peter Gray) remember a period in sixth grade when, while I was reading in school, the thought would repeatedly enter my mind that reading could make my eyes fall out. The only way I could banish this thought and go on reading was to close my eyelids down hard—a compulsive act that I fancied might push my eyes solidly back into their sockets. Of course, I knew that both the thought and the action were irrational, yet the thought kept intruding, and the only way I could abolish it for a while was to perform the action. Like most normal obsessions and compulsions, this one did not really disrupt my life, and it simply faded with time.

Characteristics of the Disorder

People who are diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are those for whom such thoughts and actions are severe, prolonged, and disruptive of normal life. To meet DSM-5 criteria for this disorder, the obsessions and compulsions must consume more than an hour per day of the person’s time and seriously interfere with work or social relationships (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). By these criteria, the disorder occurs in roughly 1 to 2 percent of people at some time in their lives (Kessler et al., 2005).

15

How is an obsessive-compulsive disorder similar to and different from a phobia? What kinds of obsessions and compulsions are most common?

Obsessive-compulsive disorder is similar to a phobia in that it involves a specific irrational fear. It is different from a phobia primarily in that the fear is of something that exists only as a thought and can be reduced only by performing some ritual. People with obsessive-compulsive disorder, like those with phobias, suffer also from their knowledge of the irrationality of their actions and often go to great lengths to hide them from other people.

The obsessions experienced by people diagnosed with this disorder are similar to, but stronger and more persistent than, the kinds of obsessions experienced by people in the general population (Mathews, 2009; Rachman & DeSilva, 1978). The most common obsessions concern disease, disfigurement, or death, and the most common compulsions involve checking or cleaning. People with checking compulsions may spend hours each day repeatedly checking doors to be sure they are locked, the gas stove to be sure it is turned off, automobile wheels to be sure they are on tight, and so on. People with cleaning compulsions may wash their hands every few minutes, scrub everything they eat, and sterilize their dishes and clothes in response to their obsessions about disease-producing germs and dirt. Some compulsions, however, bear no apparent logical relationship to the obsession that triggers them. For example, a woman obsessed by the thought that her husband would die in an automobile accident could in fantasy protect him by dressing and undressing herself in a specific pattern 20 times every day (Marks, 1987).

637

Brain Abnormalities Related to the Disorder

16

How might damage to certain areas of the brain result in obsessive-compulsive disorder?

Although all mental disorders are brain related, the role of the brain in obsessive-compulsive disorder has been relatively well documented. In some cases, the disorder first appears after known brain damage, from such causes as a blow to the head, poisons, or diseases (Berthier et al., 2001; Steketee & Barlow, 2002). Brain damage resulting from a difficult birth has also been shown to be a predisposing cause (Vasconcelos et al., 2007), and in many other cases, neural imaging has revealed brain abnormalities stemming from unknown causes (Szeszko et al., 2004).

The brain areas that seem to be particularly involved include portions of the frontal lobes of the cortex and parts of the underlying limbic system and basal ganglia (Britton & Rauch, 2009); these normally work together in a circuit to control voluntary actions, the kinds of actions that are controlled by conscious thoughts. One theory is that damage in these areas may produce obsessive-compulsive behavior by interfering with the brain’s ability to produce the psychological sense of closure or safety that normally occurs when a protective action is completed. Consistent with this theory, people with obsessive-compulsive disorder often report that they do not experience the normal sense of task completion that should come after they have washed their hands or inspected the gas stove, so they feel an overwhelming need to perform the same action again (Szechtman & Woody, 2004).

SECTION REVIEW

Anxiety disorders have fear or anxiety as their primary symptom.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- This disorder, characterized by excessive worry about real or imagined threats, may be predisposed by genes or childhood trauma and brought on by disturbing events in adulthood.

- Hypervigilance—automatic attention to possible threats—may stem from early trauma and may lead to generalized anxiety, which has become much more common in Western culture since the mid-twentieth century.

Phobias

- Phobias involve intense fear of specific nonsocial objects (such as spiders) or situations (such as heights).

- Phobia sufferers usually know that the fear is irrational but still cannot control it.

- The difference between a normal fear and a phobia is one of degree.

- Natural selection may have prepared us to fear some objects and situations more readily than others.

Panic Disorder

- People with this disorder experience bouts of helpless terror (panic attacks) unrelated to specific events in their environment.

- The disorder may be predisposed and perpetuated by a learned tendency to regard physiological arousal as catastrophic.

- Caffeine, exercise, or other ways of increasing heart and breathing rates can trigger panic attacks in susceptible people.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- This disorder is characterized by the re-experiencing—in nightmares, daytime thoughts, and flashbacks—of an emotionally traumatic event. Other symptoms include sleeplessness, irritability, guilt, and depression.

- Genetic predisposition, repeated exposures to traumatic events, and inadequate social support increase the risk for the disorder.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

- This disorder—involving repetitive, disturbing thoughts (obsessions) and repeated, ritualistic actions (compulsions)—is associated with abnormalities in an area of the brain that links conscious thought to action.

- Obsessions and compulsions are often extreme versions of normal safety concerns and protective actions, which the sufferer cannot shut off despite being aware of their irrationality.

638