16.6 Personality Disorders

30

What is a personality disorder? How is it similar to, and different from, more serious disorders such as schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder?

As we discussed in the previous chapter, personality refers to a person’s general style of interacting with the world, especially with other people. People have different personality traits, and psychologists have spent much time and effort describing these traits. But what happens when someone’s personality falls outside of the normal range, when a person’s daily style of interaction with other people is viewed as “odd” or extreme? The result is a personality disorder, defined as an enduring pattern of behavior, thoughts, and emotions that impairs a person’s sense of self, goals, and capacity for empathy and/or intimacy and is associated with significant stress and disability. It is sometimes difficult to differentiate personality disorders from somewhat extreme but “normal” personality traits on the one hand and serious forms of mental illness, such as schizophrenia, social anxiety disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder on the other hand.

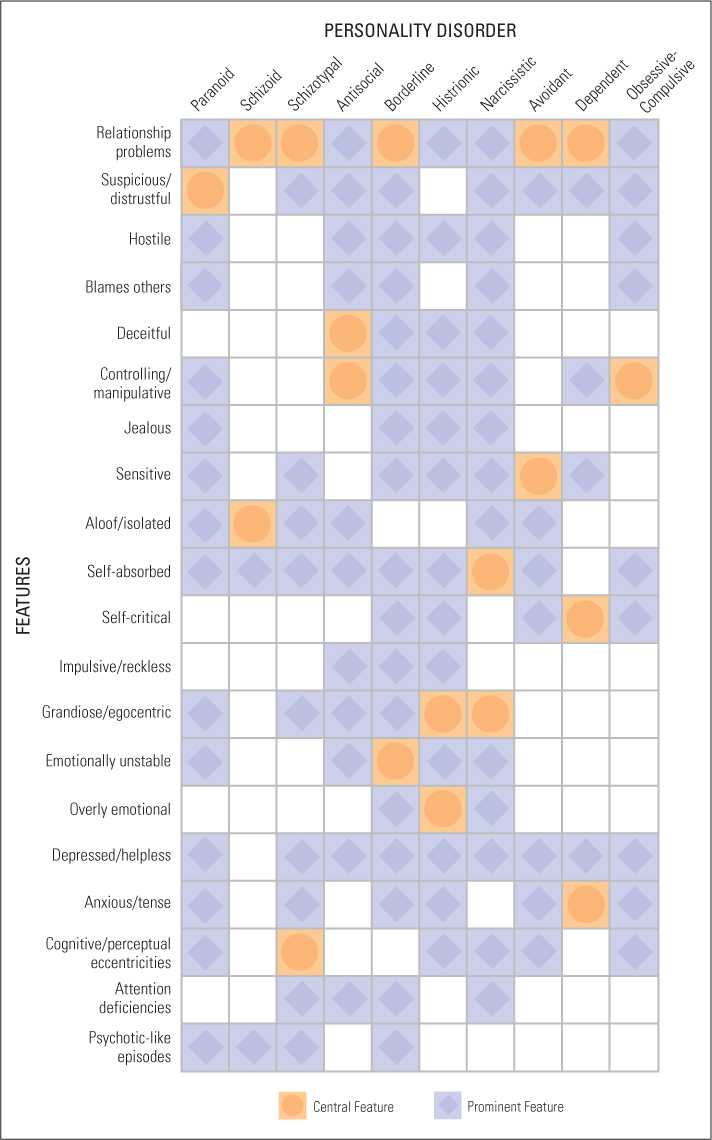

The DSM-5 identifies 10 personality disorders (see Figure 16.11), which are divided into three clusters: Cluster A (paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal); Cluster B (antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic); and Cluster C (avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive). We will examine each of these disorders briefly in the following sections. We should note that there are limitations and problems with this classification system. Many patients meet criteria for more than one personality disorder, many have personality disorders that do not fall neatly into one of the 10 categories, and personality dysfunction may reflect maladaptive extremes of normal personality trait dimensions.

Cluster A: “Odd” Personality Disorders

31

Describe the three clusters of personality disorders. Within each cluster, what means do clinicians use to differentiate the symptoms of one disorder from those of others?

This cluster of disorders has much in common with schizophrenia, especially its delusional component. In fact, people with a diagnosis of a Cluster A personality disorder often have close relatives with schizophrenia or are diagnosed themselves with schizophrenia (Chemerinski & Siever, 2011).

Paranoid Personality Disorder

As the name connotes, people with this disorder are deeply distrustful of other people and are suspicious of their motives. They frequently believe that people are “out to get them” and read hostile intentions into the actions of others (Turkat et al., 1990). Most of these attributions are inaccurate, but not so off base as to be considered delusional. They frequently blame others for their failures and tend to bear grudges (Rotter, 2011). Between .5 and 3 percent of adults display this disorder, and it appears to be more frequent in men than in women (Paris, 2010).

Mr. W. is a 53-year-old referred for psychiatric evaluation by his attorney to rule out a treatable psychiatric disorder. Mr. W. has entered into five lawsuits in the past 2½ years. His attorney believes that each suit is of questionable validity. Mr. W. has been described as an unemotional, highly controlled person who is now suing a local men’s clothing store “for conspiring to deprive me of my consumer rights.” He contends that the store manager consistently issued bad credit reports on him. The consulting psychiatrist elicited other examples of similar concerns. Mr. W. has long distrusted his neighbors across the street and regularly monitors their activity since one of his garbage cans disappeared 2 years ago. He took an early retirement from his accounting job a year ago because he could not get along with his supervisor, who he believed was faulting him about his accounts and paperwork. He contends he was faultless. On examination, Mr. W.’s mental status is unremarkable except for constriction of affect and for a certain hesitation and guardedness in his response to questions. (Sperry, 2003, pp. 200–201)

Schizoid Personality Disorder

People with this disorder display little in the way of emotion, either positive or negative, and tend to avoid social relationships. They do not avoid others because they fear or mistrust them, as people with paranoid personality disorders do, but rather because they genuinely prefer to be alone. Many are “loners” who make no effort to initiate or maintain friendships, often including sexual relations and interactions with their families. People with schizoid personality disorder tend to be self-centered and are not much influenced by either praise or criticism. This disorder is relatively rare, occurring in fewer than 1 percent of people in the population (Paris, 2010).

655

656

Schizotypal Personality Disorder

People with schizotypal personality disorder show extreme discomfort in social situations, often bizarre patterns of thinking and perceiving, and behavioral eccentricities, such as wearing odd clothing or repeatedly organizing their kitchen shelves. They tend to be anxious and distrustful of others and are often loners. They often see significance in unrelated events, especially as they relate to themselves, and some people with this disorder believe they have special abilities, such as extrasensory perception or magical control over other people. People with this disorder have poor attentional focus, making their conversations vague, often with loose associations (Millon, 2011). They find it difficult to get and keep jobs and often lead idle, unproductive lives. Schizotypal personality disorder occurs in about 2 to 4 percent of all people, and it is slightly more common in men than in women (Paris, 2010).

Cluster B: “Dramatic” Personality Disorders

This cluster includes four examples, the common link being that individuals with these disorders display highly emotional, dramatic, or erratic behavior that makes it difficult for them to have stable, satisfying relationships.

Antisocial Personality Disorder

People with this disorder consistently violate or disregard the rights of others and are sometimes referred to as sociopaths or psychopaths. They frequently lie, seem to lack a moral conscience, and behave impulsively, seemingly disregarding the consequences of their actions (Kantor, 2006; Millon, 2011). As a result of their reckless behavior and disregard for others, they frequently find themselves in trouble with the law. In fact, it is estimated that approximately 30 percent of people in the prison population meet the diagnosis criterion for antisocial personality disorder (O’Connor, 2008). In the broader population, it is estimated that between 3 and 3.5 percent of people in the United States have antisocial personality disorder, which is about four times more common in men than in women (Paris, 2010).

Juan G. is a 28-year-old Cuban male who presented late in the evening to the emergency room at a community hospital complaining of a headache. His description of the pain was vague and contradictory. At one point he said the pain had been present for 3 days, whereas at another point it was “many years.” He indicated that the pain led to violent behavior and described how, during a headache episode, he had brutally assaulted a medic while he was in the Air Force. He gave a long history of arrests for assault, burglary, and drug dealing. Neurological and mental status examinations were within normal limits except for some mild agitation. He insisted that only Darvon—a narcotic—would relieve his headache pain. The patient resisted a plan for further diagnostic tests or a follow-up clinic appointment, saying unless he was treated immediately “something really bad could happen.” (Sperry, 2003, p. 41)

Borderline Personality Disorder

The principal feature of borderline personality disorder is instability, including in emotions—swinging in and out of extreme moods—and self-image, often showing dramatic changes in identity, goals, friends, and even sexual orientation (Westen et al., 2011). Similar to people with antisocial personality disorder, they tend to be impulsive, often engaging in reckless behavior (reckless driving, unsafe sex, substance abuse), sometimes lashing out at others when things don’t go right, and other times turning their anger inward, engaging in self-injurious behavior (Chiesa et al., 2011; Coffey et al., 2011). Attempted suicide is common in people with borderline personality disorder, with, according to some estimates, about 75 percent of people with the disorder attempting suicide at least once in their lives and approximately 10 percent succeeding (Gunderson, 2011). The relationships of people with borderline personality disorder tend to be intense and stormy, and they often have fears of abandonment, resulting in frantic efforts to head off anticipated separations (Gunderson, 2011). It is estimated that between 1 and 2.5 percent of people in the population have borderline personality disorder, with most (about 75 percent) being women (Paris, 2010).

657

Histrionic Personality Disorder

People with histrionic personality disorder continually seek to be the center of attention—they behave as if they are always “on stage,” using theatrical gestures and mannerisms—and are often described as vain, self-centered, and “emotionally charged,” displaying exaggerated moods and emotions. As you can imagine, this can interfere with everyday living. People with this disorder constantly seek attention and approval from others and are concerned with how others will evaluate them, often wearing provocative clothing to attract attention. They have a difficult time delaying gratification and may overreact in order to get attention, sometimes to the point of feigning physical illness. Males and females are equally likely to be classified as having histrionic personality disorder, with between 2 and 3 percent of people in the population having the disorder (Paris, 2010).

Ms. P is a 20-year-old female undergraduate student who requested psychological counseling at the college health services for “boyfriend problems.” Actually, she had taken a nonlethal overdose of minor tranquilizers the day before coming to the health services. She said she took the overdose in an attempt to kill herself because “life wasn’t worth living” after her boyfriend had left the afternoon before. She is an attractive, well-dressed woman adorned with make-up and nail polish, which contrasts sharply with the very casual fashion of most coeds on campus. During the initial interview she was warm and charming, maintained good eye contact, yet was mildly seductive. At two points in the interview she was emotionally labile, shifting from smiling elation to tearful sadness. Her boyfriend had accompanied her to the evaluation session and asked to talk to the clinician. He stated the reason he had left the patient was because she made demands on him that he could not meet and that he “hadn’t been able to satisfy her emotionally or sexually.” Also, he noted that he could not afford to “take her out every night and party.” (Sperry, 2003, p. 134)

Narcissistic Personality Disorder

People with this disorder are even more self-centered than people with borderline personality disorder. They seek admiration from others, tend to lack empathy, and are grandiose and overconfident in their own exceptional talents or characteristics. They exaggerate their abilities and achievements and expect others to see the same exceptional qualities in them that they see in themselves. As a result, they are frequently perceived as arrogant. They often make good first impressions (their social skills tend to be relatively good), but these are rarely maintained (Campbell & Miller, 2011). This is due in part to their perceived arrogance, but also to their general lack of interest in other people (Ritter et al., 2011). It is estimated that approximately 1 percent of people in the population show narcissistic personally disorder, with 75 percent of them being men (Dhwan et al., 2010).

658

Cluster C: “Anxious” Personality Disorders

The common thread for this final cluster of personality disorders is fear and anxiety. People with anxious personality disorders have much in common with people who suffer from depression and anxiety disorder; the difference is one of degree.

Avoidant Personality Disorder

People with this disorder are excessively shy; they are uncomfortable and inhibited in social situations. They feel inadequate and are extremely sensitive to being evaluated, experiencing a dread of criticism. Their extreme fear of rejection causes them to be timid and fearful in social settings and often results in their avoiding social contact, making it impossible for them to be accepted. People with avoidant personality disorder rarely take risks or try out new activities, exaggerating the difficulty of tasks before them (Rodenbaugh et al., 2010). Avoidant personality disorder is similar to generalized anxiety disorder discussed earlier in this chapter (p. 631), and people are sometimes classified with both disorders (Cox et al., 2011). Approximately 1 to 2 percent of people in the population are afflicted with this disorder, men and women with comparable frequency (Paris, 2010).

Dependent Personality Disorder

People with dependent personality disorder show an extreme need to be cared for. They are clingy and fear separation from significant people in their lives, believing they cannot care for themselves. People with dependent personality disorder fear upsetting relationship partners (their partners may leave them if they do), and as a result tend to be obedient, rarely disagreeing with them and permitting them to make important decisions for them (Millon, 2011). They often feel lonely, sad, and distressed, putting them at high risk for anxiety, depression, and eating disorders (Bornstein, 2007). They are prone to suicidal thoughts, especially when a relationship is breaking up. It is estimated that between 2 and 3 percent of people in the population suffer from dependent personality disorder, with about the same number of men and women having the disorder (Paris, 2010).

Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder

Like people with obsessive-compulsive disorder, people with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder are preoccupied with order and control, and as a result are inflexible and resist change. They are so highly focused on the details of a task that they often fail to understand the point of an activity. They tend to set excessively high standards for themselves and others, exceeding any normal degree of conscientiousness (Samuel & Widiger, 2011). They often have difficulty expressing affection, and as a result their relations are frequently shallow and superficial. Approximately 1 to 2 percent of people in the population show obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, with about twice as many men having the disorder as women (Paris, 2010).

659

Origins of Personality Disorders

There is no lack of theorizing about the origins of personality disorders, but generally less research has been done investigating the causes of these disorders than many other disorders such as depression or schizophrenia (Bernstein & Useda, 2007). Biological explanations, such as possible genetic and neurotransmitter causes, have been proposed for some personality disorders. For example, some studies report a genetic connection for paranoid personality disorder (Kendler et al., 1987), abnormalities in neurotransmitters have been identified for schizotypal and antisocial personality disorders (Hazlett et al., 2011; Patrick, 2007), and abnormalities in brain structures have been found for schizotypal, antisocial, and borderline personality disorders (see Comer, 2014). Experiences in childhood have been shown to be related to schizotypal, antisocial, borderline, and dependent personality disorders (see Comer, 2014); and sociocultural explanations have been proposed for narcissistic (family values in Western societies promote narcissism; Campbell & Miller, 2011) and histrionic (some cultures are more accepting of extreme behavior than others; Patrick, 2007) personality disorders. As with other forms of mental disorders, it is almost certain that there are multiple causes of any single personality disorder, with genes, operating in interaction with the environment at all levels (for example, family, culture), influencing brain structure (formation of synapses, pruning of neurons, abundance of neurotransmitter receptors) and function (through presence of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate). Also, although according to the DMS-5 a person must be at least 18 years old to be diagnosed with a personality disorder, the roots of such disorders are in development, with features of all of these disorders being apparent to lesser degrees during childhood and adolescence.

SECTION REVIEW

Personality Disorders

- Personality disorders refer to stable patterns of behavior that impair a person’s sense of self, goals, and capacity for empathy and/or intimacy. They are often divided into three clusters.

- Cluster A (“odd”) personality disorders include paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal types, all characterized by some degree of delusions and erratic behavior.

- Cluster B (“dramatic”) personality disorders include antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic types and are characterized by highly emotional, dramatic, or erratic behavior.

- Cluster C (“anxious”) personality disorders include avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive types and are characterized by fear and anxiety.

- The origins of personality disorders have not received as much investigation as other forms of mental disorders, but are surely the result of gene–environment interaction affecting the brain over the course of development.