17.3 Psychotherapy I: Psychodynamic and Humanistic Therapies

While biological treatment for mental disorders aims to improve moods, thinking, and behavior through altering the chemistry and physiology of the brain, psychological treatment, referred to as psychotherapy, aims to improve the same through talk, reflection, learning, and practice.

The two approaches—biological and psychological—are not incompatible. Indeed, most clinicians believe that the best treatment for many people who suffer from serious mental disorders involves a combination of drug therapy and psychotherapy. In theory as well as in practice, the biological and the psychological are tightly entwined. Changes of any sort in the brain can alter the way a person feels, thinks, and behaves; and changes in feeling, thought, and behavior can alter the brain. The brain is not a “hard-wired” machine. It is a dynamic biological organ that is constantly growing new neural connections and losing old ones as it adapts to new experiences and thoughts.

Psychotherapy can be defined as any theory-based, systematic procedure, conducted by a trained therapist, for helping people to overcome or cope with mental problems through psychological rather than directly physiological means. Psychotherapy usually involves dialogue between the person in need and the therapist, and its aim is usually to restructure some aspect of the person’s way of feeling, thinking, or behaving. If you have ever helped a child overcome a fear, encouraged a friend to give up a bad habit, or cheered up a despondent roommate, you have informally engaged in a process akin to psychotherapy.

674

One count, made a number of years ago, identified more than 400 nominally different forms of psychotherapy (Corsini & Wedding, 2011). Psychotherapists may work with groups of people, or with couples or families, as well as with individuals. In this chapter, however, our discussion is limited to four classic varieties of individual therapy. We examine psychodynamic and humanistic therapies in this section, and cognitive and behavioral therapies in the next.

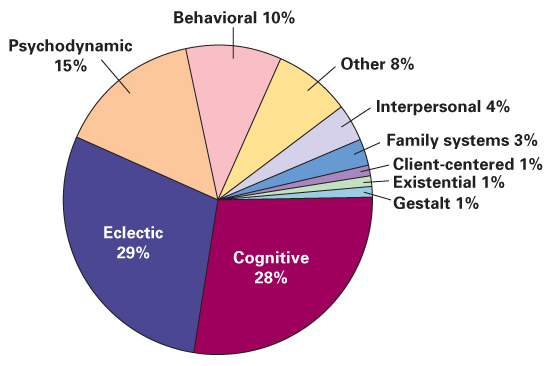

There was a time when many psychotherapists believed that their own approach was “right” and other approaches “wrong.” Today, however, most therapists recognize strengths and weaknesses in each of the classic schools of thought in psychotherapy. As shown in Figure 17.2, nearly 30 percent of contemporary psychotherapists consider themselves to be “eclectic” or “integrative” in orientation—that is, they do not identify with any one school of thought but use methods gleaned from various schools. Even among those who do identify with a particular school of thought, most borrow techniques and ideas from other schools.

As you will discover as you read about them, each major approach in psychotherapy draws on a set of psychological principles and ideas that apply to adaptive as well as to maladaptive behavior.

- The psychodynamic approach focuses on the idea that unconscious memories and emotions influence our conscious thoughts and actions.

- The humanistic approach focuses on the value of self-esteem and self-direction, and on the idea that people often need psychological support from others in order to pursue freely their own chosen goals.

- The cognitive approach focuses on the idea that people’s ingrained, habitual ways of thinking affect their moods and behavior.

- The behavioral approach focuses on the roles of basic learning processes in the development and maintenance of adaptive and maladaptive ways of responding to the environment.

Principles of Psychodynamic Therapies

Sigmund Freud, whose theory of personality was discussed in Chapter 15, was the primary founder of psychodynamic psychotherapy. As noted in Chapter 15, Freud used the term psychoanalysis to refer to both his theory of personality and his methods of therapy. Today the term psychoanalysis is generally used to refer to those forms of therapy that adhere most closely to the ideas set forth by Freud, and the broader term psychodynamic therapy is used to include psychoanalysis and therapies that are more loosely based on Freud’s ideas. In a 2001 survey, only 10 percent of those who categorized their therapy as psychodynamic identified their specific method as psychoanalysis (Bechtoldt et al., 2001). In what follows, we set forth some of the main principles and methods that are common to most, if not all, psychodynamic therapies.

675

The Idea That Unconscious Conflicts, Often Deriving from Early Childhood Experiences, Underlie Mental Disorders

10

According to psychodynamic therapists, what are the underlying sources of mental disorders?

The most central, uniting idea of all psychodynamic theories is that mental problems arise from unresolved mental conflicts, which themselves arise from the holding of contradictory motives and beliefs. The motives, beliefs, and conflicts may be unconscious, or partly so, but they nevertheless influence conscious thoughts and actions. The word dynamic refers to force, and psychodynamic refers to the forceful, generally unconscious influences that conflicting motives and beliefs can have on a person’s consciously experienced emotions, thoughts, and behavior.

Freud himself argued (such as Freud, 1933/1964) that the unconscious conflicts that cause trouble always originate in the first 5 or 6 years of life and have to do with infantile sexual and aggressive wishes, but few psychodynamic therapists today have retained that view. Most psychodynamic therapists today are concerned with conflicts that can originate at any time in life and have to do with any drives or needs that are important to the person. Still, however, most such therapists tend to see sexual and aggressive drives as particularly important, as these drives often conflict with learned beliefs and societal constraints. They also tend to see childhood as a particularly vulnerable period during which frightening or confusing experiences can produce lasting marks on a person’s ways of feeling, thinking, and behaving. Such experiences might derive from such sources as sexual or physical abuse, lack of security, or lack of consistent love from parents.

In general, psychodynamic theorists see their approach as tightly linked, theoretically, to the field of developmental psychology. In their view, growing up necessarily entails the facing and resolving of conflicts; conflicts that are not resolved can produce problems later in life (Thompson & Cotlove, 2005).

The Idea That Patients’ Observable Speech and Behavior Provide Clues to Their Unconscious Conflicts

11

According to psychodynamic therapists, what is the relationship between symptoms and disorders?

To a psychodynamic therapist, the symptoms that bring a person in for therapy and that are used to label a disorder, using DSM-5 or any other diagnostic guide, are just that—symptoms. They are surface manifestations of the disorder; the disorder itself is buried in the person’s unconscious mind and must be unearthed before it can be treated.

For example, consider a patient who is diagnosed as having anorexia nervosa (an eating disorder discussed in Chapter 16). To a psychodynamic therapist, the fundamental problem with the person is not the failure to eat but is something deeper and more hidden—some conflict that makes her want to starve herself. Two people who have similar symptoms and identical diagnoses of anorexia nervosa may suffer from quite different underlying conflicts. One might be starving herself because she fears sex, and starvation is a way of forestalling her sexual development; another might be starving herself because she feels unaccepted for who she is, so she is trying to disappear. To a psychodynamic therapist, the first step in treatment of either patient is finding out why she is starving herself; quite likely, she herself is not conscious of the real reason (Binder, 2004).

To learn about the content of a patient’s unconscious mind, the psychodynamic therapist must, in detective-like fashion, analyze clues found in the patient’s speech and other forms of observable behavior. This is where Freud’s term psychoanalysis comes from. The symptoms that brought the patient in for help, and the unique ways those symptoms are manifested, are one source of clues that the therapist considers. What other clues might be useful? Since the conscious mind usually attempts to act in ways that are consistent with conventional logic, Freud reasoned that the elements of thought and behavior that are least logical would provide the most useful clues. They would represent elements of the unconscious mind that leaked out relatively unmodified by consciousness. This insight led Freud to suggest that the most useful clues to a patient’s unconscious motives and beliefs are found in the patient’s free associations, dreams, and slips of the tongue or behavioral errors. These sources of clues are still widely used by psychodynamic therapists.

676

Free Associations as Clues to the Unconscious The technique of free association is one in which the patient is encouraged to sit back (or, in traditional psychoanalysis, to lie down on a couch), relax, free his or her mind, refrain from trying to be logical or “correct,” and report every image or idea that enters his or her awareness, usually in response to some word or picture that the therapist provides as an initial stimulus. You might try this exercise yourself: Relax, free your mind from what you have just been reading or thinking about, and write down the words or ideas that come immediately to your mind in response to each of the following: liquid, horse, soft, potato. Now, when you examine your set of responses to these words, do they make any sense that was not apparent when you produced them? Do you believe that they give you any clues to your unconscious mind?

12

How do psychodynamic therapists use patients’ free associations, dreams, and “mistakes” as routes to learn about their unconscious minds?

Dreams as Clues to the Unconscious Freud believed that dreams are the purest exercises of free association, so he asked patients to try to remember their dreams, or to write them down upon awakening, and to describe them to him. During sleep, conventional logic is largely absent, and the forces that normally hold down unconscious ideas are weakened. Still, even in dreams, according to Freud and other psychodynamic therapists, the unconscious is partially disguised. Freud distinguished the underlying, unconscious meaning of the dream (the latent content) from the dream as it is consciously experienced and remembered by the dreamer (the manifest content). The analyst’s task in interpreting a dream is the same as that in interpreting any other form of free association: to see through the disguises and uncover the latent content from the manifest content.

Psychodynamic therapists hold that the disguises in dreams come in various forms. Some are unique to a particular person, but some are common to many people. Freud himself looked especially for sexual themes in dreams, and the common disguises that he wrote about have become known as Freudian symbols, some of which he described as follows (from Freud, 1900/1953):

677

The Emperor and Empress (or King and Queen) as a rule really represent the dreamer’s parents; and a Prince or Princess represents the dreamer himself or herself…. All elongated objects, such as sticks, tree-trunks, and umbrellas (the opening of these last being comparable to an erection) may stand for the male organ—as well as all long, sharp weapons, such as knives, daggers, and pikes…. Boxes, cases, chests, cupboards, and ovens represent the uterus, and also hollow objects, ships, and vessels of all kinds. Rooms in dreams are usually women; if the various ways in and out of them are represented, this interpretation is scarcely open to doubt. In this connection interest in whether the room is open or locked is easily intelligible. There is no need to name explicitly the key that unlocks the room. (p. 353)

Mistakes and Slips of the Tongue as Clues to the Unconscious Still other clues to the unconscious mind, used by psychodynamic therapists, are found in the mistakes that patients make in their speech and actions. In Freud’s rather extreme view, mistakes are never simply random accidents but are always expressions of unconscious wishes or conflicts. In one of his most popular books, The Psychopathologie of Everyday Life, Freud (1901/1990) supported this claim with numerous, sometimes amusing examples of such errors, along with his interpretations.

The Roles of Resistance and Transference in the Therapeutic Process

13

In psychodynamic therapy, how do resistance and transference contribute to the therapeutic process?

From Freud’s time through today, psychodynamic therapists have found that patients often resist the therapist’s attempt to bring their unconscious memories or wishes into consciousness (Weiner & Bornstein, 2009). The resistance may manifest itself in such forms as refusing to talk about certain topics, “forgetting” to come to therapy sessions, or persistently arguing in a way that subverts the therapeutic process. Freud assumed that resistance stems from the general defensive processes by which people protect themselves from becoming conscious of anxiety-provoking thoughts. Resistance provides clues that therapy is going in the right direction, toward critical unconscious material; but it can also slow down the course of therapy or even bring it to a halt. To avoid triggering too much resistance, the therapist must present interpretations gradually, when the patient is ready to accept them.

Freud also observed that patients often express strong emotional feelings—sometimes love, sometimes anger—toward the therapist. Freud believed that the true object of such feelings is usually not the therapist but some other significant person in the patient’s life whom the therapist symbolizes. Thus, transference is the phenomenon by which the patient’s unconscious feelings about a significant person in his or her life are experienced consciously as feelings about the therapist. Psychodynamic therapists to this day consider transference to be especially useful in psychotherapy because it provides an opportunity for the patient to become aware of his or her strong emotions (Weiner & Bornstein, 2009). With help from the analyst, the patient can gradually become aware of the origin of those feelings and their true target.

The Relationship Between Insight and Cure

14

According to psychodynamic theories, how do insights into the patient’s unconscious conflicts bring about a cure?

Psychodynamic therapy is essentially a process in which the analyst makes inferences about the patient’s unconscious conflicts and helps the patient become conscious of those conflicts. How does such consciousness help? According to psychodynamic therapists from Freud on, it helps because, once conscious, the conflicting beliefs and wishes can be experienced directly and acted upon; or, if they are unrealistic, they can be modified by the conscious mind into healthier, more appropriate beliefs and pursuits (Thompson & Cotlove, 2005). At the same time, the patient is freed of the defenses that had kept that material repressed and has more psychic energy for other activities. But for all this to happen, the patient must truly accept the insights, viscerally as well as intellectually. The therapist cannot just tell the patient about the unconscious conflicts but must lead the patient gradually to actually experience the emotions and to arrive at the insights him- or herself.

678

Principles of Humanistic Therapy

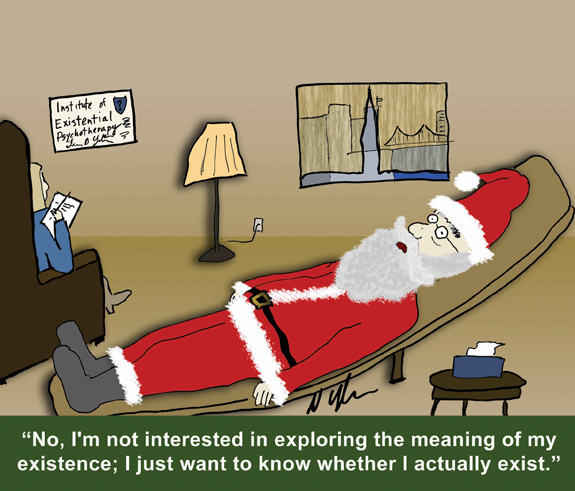

The humanistic movement in psychology originated in the mid-twentieth century. It grew partly out of existentialist philosophy, which focuses on the idea that human beings create their own life meanings (Hazler & Barwick, 2001), as well as a reaction against the psychodynamic approach, which puts control in the hands of the analyst rather than the patient. From an existentialist perspective, each person must decide for him- or herself what is true and worthwhile in order to live a full, meaningful life; meaning and purpose cannot be thrust upon a person from the outside.

Two fundamental psychological ideas that have been emphasized repeatedly in previous chapters of this book are these: (1) People have the capacity to make adaptive choices regarding their own behavior—choices that promote their survival and well-being. (2) In order to feel good about themselves and to feel motivated to move forward in life, people need to feel accepted and approved of by others. No approach to psychotherapy takes these two ideas more seriously than does the humanistic approach.

15

What is the primary goal of humanistic therapy? How does that goal relate to existentialist philosophy?

As described in Chapter 15, the humanistic view of the person emphasizes the inner potential for positive growth—the so-called actualizing potential. Recall that the highest level in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (refer back to page 603) is self-actualization. For this self-actualizing potential to exert its effects, people must be conscious of their feelings and desires, not deny or distort them. Denial and distortion occur when people perceive that others who are important to them consistently disapprove of their feelings and desires. The goal of humanistic therapy is to help people regain awareness of their own desires and control of their own lives.

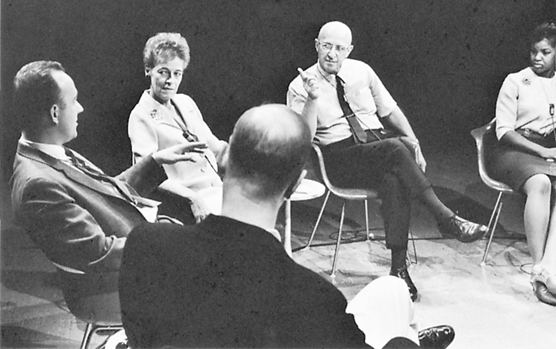

The primary founder of humanistic psychotherapy was Carl Rogers, whose theory of personality was introduced in Chapter 15. Rogers (1951) called his therapeutic approach client-centered therapy, a term deliberately chosen to distinguish it from psychodynamic therapies. Client-centered therapy focuses on the abilities and insights of the client rather than those of the therapist. Practitioners of this approach today, however, more often refer to it as person-centered therapy because they see the therapeutic process as involving a relationship between two unique persons—the client and the therapist (Mearns & Thorne, 2000; Wilkins, 2003). The therapist must attend to his or her own thoughts and feelings, as well as to those of the client, in order to respond in a supportive yet honest way to the client (Raskin et al., 2011).

The core principles of person-centered therapy all have to do with the relationship between the therapist and the client. The therapist lets the client take the lead in therapy, strives to understand and empathize with the client, and endeavors to think positively and genuinely of the client as a competent, valuable person. Through these means, the therapist tries to help the client regain the self-understanding and confidence necessary to control his or her own life.

Allowing the Client to Take the Lead

16

According to humanistic therapists, how do the therapist’s nondirective approach, empathic listening, and genuine positive regard contribute to the client’s recovery?

Humanistic psychotherapists usually refer to those who come to them for help as clients, not as patients, because the latter term implies passivity and lack of ability. In humanistic therapy, at least in theory, the client is in charge; it is the therapist who must be “patient” enough to follow the client’s lead. The therapist may take steps to encourage the client to start talking, to tell his or her story; but once the client has begun to talk it is the therapist’s task to understand, not to direct the discussion or interpret the client’s words in ways that the client does not. While psychodynamic theorists may strain their patients’ credulity with far-reaching interpretations, humanistic therapists more often just paraphrase what the client said, as a way of checking to be sure that they understood correctly.

679

Listening Carefully and Empathetically

The humanistic therapist tries to provide a context within which clients can become aware of and accept their own feelings and learn to trust their own decisionmaking abilities. To do so, the therapist must first and foremost truly listen to the client in an empathetic way (Raskin et al., 2011; Rogers, 1951). Empathy here refers to the therapist’s attempt to comprehend what the client is saying or feeling at any given moment from the client’s point of view rather than as an outsider. As part of the attempt to achieve and manifest such empathy, the therapist frequently reflects back the ideas and feelings that the client expresses. A typical exchange might go like this:

Client: My mother is a mean, horrible witch!

Therapist: I guess you’re feeling a lot of anger toward your mother right now.

To an outsider, the therapist’s response here might seem silly, a statement of the obvious. But to the client and therapist fully engaged in the process, the response serves several purposes. First, it shows the client that the therapist is listening and trying to understand. Second, it distills and reflects back to the client the feeling that seems to lie behind the client’s words—a feeling of which the client may or may not have been fully aware at the moment. Third, it offers the client a chance to correct the therapist’s understanding. By clarifying things to the therapist, the client clarifies them to him- or herself.

Providing Unconditional but Genuine Positive Regard

Unconditional positive regard implies a belief on the therapist’s part that the client is worthy and capable even when the client may not feel or act that way. By expressing positive feelings about the client regardless of what the client says or does, the therapist creates a safe, nonjudgmental environment for the client to explore and express all of his or her thoughts and feelings. Through experiencing the therapist’s positive regard, clients begin to feel more positive about themselves, an essential step if they are going to take charge of their lives. Unconditional positive regard does not imply agreement with everything the client says or approval of everything the client does, but it does imply faith in the client’s underlying capacity to make appropriate decisions. Consider the following hypothetical exchange:

Client: Last semester in college I cheated on every test.

Therapist: I guess what you’re saying is that last semester you did something against your values.

Notice that the therapist has said something positive about the client in relation to the misdeed without condoning the misdeed. The shift in focus from the negative act to the client’s positive values affirms the client’s inner worth and potential ability to make constructive decisions.

Humanistic therapists must work hard to be both positive and genuine in the feedback they supply to clients. They contend that it is impossible to fake empathy and positive regard, that the therapist must really experience them. If the therapist’s words and true feelings don’t match, the words will not be believable to the client. The capacity for genuine empathy and positive regard toward all clients might seem to be a rare quality, but Rogers suggests that it can be cultivated by deliberately trying to see things as the client sees them.

680

Although few psychotherapists identify themselves as practicing client-centered therapy today (see Figure 17.2), aspects of Roger’s approach can be seen in some modern forms of therapy. For example, emotionally focused therapy is a brief (8 to 20 sessions) form of therapy that adopts many of the practices of client-centered therapy but emphasizes the importance of emotion, particularly emotions related to attachment (Greenberg & Goldman, 2008; Palmer-Olsen et al., 2011). Emotionally focused therapy, which is often used for couples and family therapy, emphasizes that relationships are attachment bonds and that effective therapy must address the security of those bonds, with change involving new experiences of the self and others, and that emotion is the target of change. Consistent with client-centered therapy, the role of the therapist is to serve as a consultant for the individuals in therapy (Johnson, 2002).

SECTION REVIEW

Talk, reflection, learning, and practice are the tools psychotherapists use to help people.

Principles of Psychodynamic Therapies

- The psychodynamic approach assumes that mental disorders arise from unresolved mental conflicts that, though unconscious, strongly influence conscious thought and action.

- The psychodynamic therapist’s job is to identify the unconscious conflict from observable clues, such as dreams, free association, mistakes, and slips of the tongue. The goal is to help the patient become aware of the conflicting beliefs and wishes and thus be able to deal with them.

- The patient’s resistance to the uncovering of unconscious material suggests that the therapist is on the right track. Transference of feelings about significant persons in the patient’s life to the therapist helps the patient become aware of these strong emotions.

Principles of Humanistic Therapies

- Humanistic therapists strive to help clients accept their own feelings and desires, a prerequisite for self-actualization (positive, self-directed psychological growth).

- Clients may fail to accept (deny and distort) their feelings and desires because they perceive that these are disapproved of by valued others.

- The humanistic therapist lets clients take the lead, listens carefully and empathetically, and provides unconditional but genuine positive regard.