17.5 Evaluating Psychotherapies

28

Why is it important to rely on experiments rather than case studies to assess the effectiveness of psychotherapy?

You have just read about four major varieties of psychotherapy. Do they work? That might seem like an odd question at this point. After all, didn’t Beck and his associates cure the depressed young woman, and didn’t behavior therapy cure Miss Muffet’s phobia? But case studies—even thousands of them—showing that people are better off at the end of therapy than at the beginning—cannot tell us for sure that therapy works. Maybe those people would have improved anyway, without therapy.

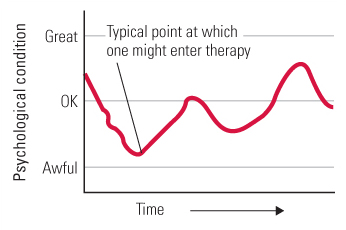

An adage about the common cold goes like this: “Treat a cold with the latest remedy, and you’ll get rid of it in 7 days; leave it untreated, and it’ll hang on for a week.” Maybe psychological problems or disorders are often like colds in this respect. Everyone has peaks and valleys in life, and people are most likely to start therapy while in one of the valleys (see Figure 17.5). Thus, even if therapy has no effect, most people will feel better at some time after entering it than they did when they began (a point that was made earlier in this chapter in the discussion of drug treatments). The natural tendency for both therapist and client is to attribute the improvement to the therapy, but that attribution may often be wrong.

Is Psychotherapy Helpful, and Are Some Types of It More Helpful Than Others?

The only way to know if psychotherapy really works is to perform controlled experiments, in which groups of people undergoing therapy are compared with otherwise-similar control groups who are not undergoing therapy. In fact, in the United States and the United Kingdom, there is a growing movement for evidence-based treatment, using only therapies that have been shown empirically to be effective (Carroll, 2012; Sharf, 2012).

A Classic Example of a Therapy-Outcome Experiment

29

How did an experiment in Philadelphia demonstrate the effectiveness of behavior therapy and psychodynamic therapy?

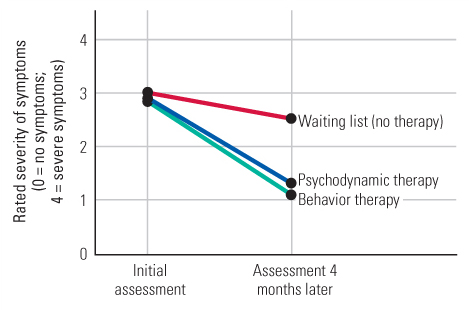

One of the earliest well-controlled experiments on therapy outcome was conducted at a psychiatric outpatient clinic in Philadelphia (Sloane et al., 1975). The subjects were 94 men and women, ages 18 to 45, who sought psychotherapy at the clinic. Most of them suffered from diffuse anxiety, the type that today would probably be diagnosed as generalized anxiety disorder. Each was assigned by a random procedure to one of three groups. Members of one group received once-a-week sessions of behavior therapy for 4 months (including such procedures as imaginal exposure to various feared situations and training in assertiveness) from one of three highly experienced behavior therapists. Members of the second group received the same amount of psychodynamic therapy (including such procedures as probing into childhood memories, dream analysis, and interpretation of resistance) from one of three highly experienced psychodynamic therapists. The members of the third group, the no-therapy group, were placed on a waiting list and given no treatment during the 4-month period but were called periodically to let them know that they would eventually be accepted for therapy.

689

To measure treatment effectiveness, all subjects, including those in the no-therapy group, were assessed both before and after the 4-month period by psychiatrists who were not informed of the groups to which the subjects had been assigned. As illustrated in Figure 17.6, all three groups improved during the 4-month period, but the treatment groups improved significantly more than did the no-treatment group. Moreover, the two treatment groups did not differ significantly from each other in degree of improvement.

This early study anticipated the result of hundreds of other psychotherapy-outcome experiments that have followed it. Overall, such research provides compelling evidence that psychotherapy works, but little if any evidence that one variety of therapy is regularly better than any other standard variety (Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Luborsky et al., 2006; Staines, 2008).

Evidence That Psychotherapy Helps

30

What is the evidence that psychotherapy works and that for some disorders it works as well as, or better than, standard drug treatments?

When hundreds of separate therapy-outcome experiments are combined, the results indicate, very clearly, that therapy helps. In fact, about 75 to 80 percent of people in the psychotherapy condition in such experiments improved more than did the average person in a nontherapy condition (Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Prochaska & Norcross, 2010). Experiments comparing the effectiveness of psychotherapy with standard drug therapies indicate, overall, that psychotherapy is at least as effective as drug therapy in treating depression and generalized anxiety disorder and is more effective than drug therapy in treating panic disorder (Imel et al., 2008; Gould et al., 1995; Mitte, 2005).

A note of caution should be added, however, for interpreting such findings. Psychotherapy-outcome experiments are usually carried out at clinics associated with major research centers. The therapists are normally highly experienced and, since they know that their work is being evaluated, they are presumably functioning at maximal capacity. It is quite possible that the outcomes in these experiments are more positive than are the average therapy outcomes, where therapists are not always so experienced or so motivated (Lambert & Ogles, 2004). Moreover, just as in the case of drug studies, there is a bias for researchers to publish results that show significant positive effects of psychotherapy and not to publish results that show no effects. This, too, would lead to an overestimation of therapy effectiveness, since the analyses are usually based only on the published findings (Staines, 2008).

Evidence That No Type of Therapy Is Clearly Better, Overall, Than Other Standard Types

31

What general conclusions have been drawn from research comparing different forms of psychotherapy?

There was a time when psychotherapists who adhered to one variety of therapy argued strongly that their variety was greatly superior to others. Such arguments have largely been quelled by the results of psychotherapy-outcome experiments. Taken as a whole, such experiments provide no convincing evidence that any of the major types of psychotherapy is superior to any other for treating the kinds of problems—such as depression and generalized anxiety—for which people most often seek treatment (Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Staines, 2008; Wampold, 2001). Most such experiments have pitted some form of cognitive or cognitive-behavioral therapy against some form of psychodynamic therapy. When the two forms of therapy are given in equal numbers of sessions, by therapists who are equally well trained and equally passionate about the value of the therapy they administer, the usual result is no difference in outcome; people treated by either therapy get better at about the same rate. Relatively few studies have compared humanistic forms of therapy with others, but the results of those few suggest that humanistic therapy works as well as the others (Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Smith et al., 1980), at least for the types of problems that were assessed.

690

Although research shows that most therapies have comparable benefits, that does not mean that every therapy is equally effective for every disorder. Some experts agree that behavioral exposure treatment is the most effective treatment for phobias (Antony & Barlow, 2002). There is also some reason to believe that cognitive and behavior therapies generally work best for clients who have rather specific problems—problems that can be zeroed in on by the specific techniques of those therapies—and that psychodynamic and humanistic therapies may be most effective for clients who have multiple or diffuse problems or problems related to their personalities (Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Siev & Chambless, 2007). And for posttraumatic stress disorder, therapies that focus on patients’ trauma memories or that encourage them to find meaning in the traumatic experience produce better results than therapies that do not (Ehler et al., 2010).

One reason for the general equivalence in effectiveness of different therapies may be that they are not as different in practice as they are in theory. Analyses of recorded therapy sessions have revealed that good therapists, regardless of the type of therapy they claim to practice, often use methods that overlap with other types of therapy. For example, effective cognitive and behavior therapists, who are normally quite directive, tend to become nondirective—more like humanistic therapists—when working with clients who seem unmotivated to follow their lead (Barlow, 2004; Beutler & Harwood, 2000). Similarly, psychodynamic therapists often use cognitive methods (such as correcting maladaptive automatic thoughts), and cognitive therapists often use psychodynamic methods (such as asking clients to talk about childhood experiences), to degrees that seem to depend on the client’s personality and the type of problem to be solved (Weston et al., 2004).

The Role of Common Factors in Therapy Outcome

Ostensibly different types of psychotherapy are similar to one another not just because the therapists borrow one another’s methods but also because all, or at least most, therapies, regardless of theoretical orientation, share certain common factors. These factors may be more important to the effectiveness of therapy than are the specific, theory-derived factors that differentiate therapies from one another (Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Sharf, 2012). Many common factors have been proposed, but we find it useful to distill them into three fundamental categories: support, hope, and motivation.

Support

32

How might support, hope, and motivation be provided within the framework of every standard type of psychotherapy? What evidence suggests that these common factors may be crucial to the therapy’s effectiveness?

Support includes acceptance, empathy, and encouragement. By devoting time to the client, listening warmly and respectfully, and not being shocked at the client’s statements or actions, any good psychotherapist communicates the attitude that the client is a worthwhile human being. This support may directly enhance the client’s self-esteem and indirectly lead to other improvements as well. Many therapy studies have demonstrated the value of such support. One long-term study, for example, revealed that psychodynamic therapists provide more support and less insight to their clients than would be expected from psychoanalytic theory (Wallerstein, 1989). The same study also showed that support, even without insight, seemed to produce stable therapeutic gains. Another study, of cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression, revealed that the bond of rapport that clients felt with their therapists early in treatment was a good predictor of their subsequent improvement (Klein et al., 2003). In yet another study, college professors with no training in psychology or methods of therapy, but with reputations for good rapport with students, proved able to help depressed college students in twice-a-week therapy sessions as effectively as did highly trained and experienced clinical psychologists (Strupp & Hadley, 1979).

691

Results such as these led one prominent psychodynamic therapist, Hans Strupp (1989), to the following conclusion: “The first and foremost task for the therapist is to create an accepting and empathic context, which in itself has great therapeutic value because for many people it is a novel and deeply gratifying experience to be accepted and listened to respectfully.”

Hope

Hope, for a suffering person, is the expectation that things will get better, that life will become more enjoyable. In psychotherapy, hope may come partly from the sense of support, but it may also come from faith in the therapy process.

Most psychotherapists believe in what they do. They speak with authority and confidence about their methods, and they offer scientific-sounding theories or even data to back up their confidence. Thus, clients also come to believe that their therapy will work. Many studies have shown that people who believe they will get better have an improved chance of getting better, even if the specific reason for the belief is false. As was discussed earlier in the chapter, patients who take an inactive placebo pill are likely to improve if they believe that they are taking a drug that will help them. Belief in the process is at least as important for improvement in psychotherapy as it is in drug therapy (Wampold et al., 2005). Hope derived from faith in the process is an element that all sought-after healing procedures have in common, whether provided by psychotherapists, medical doctors, faith healers, or folk healers.

Many researchers have designed psychotherapy-outcome experiments that compare accepted forms of psychotherapy with made-up, “false” forms of psychotherapy—forms that lack the specific ingredients that mark any well-accepted type of therapy. For example, in one such study, cognitive-behavioral therapy for problems of anxiety was compared with a made-up treatment called “systematic ventilation,” in which clients talked about their fears in a systematic manner (Kirsch et al., 1983). A general problem with such studies is that it is hard for therapists to present the “false” therapy to clients in a convincing manner, especially if the therapists themselves don’t believe it will work. Yet, analyses of many such studies indicate that when the “false” therapy is equivalent to the “real” therapy in credibility to the client, it is also generally equivalent in effectiveness (Ahn & Wampold, 2001; Baskin et al., 2003).

Motivation

Psychotherapy is not a passive process; it is not something “done to” the client by the therapist. The active agent of change in psychotherapy is the client him- or herself. This is an explicit tenet of humanistic therapy and an implicit tenet of other therapies (Hazler & Barwick, 2001). To change, the client must work at changing, and such work requires strong motivation. Motivation for change comes partly from the support and hope engendered by the therapist, which make change seem worthwhile and feasible, but it also comes from other common aspects of the psychotherapy process.

Every form of psychotherapy operates in part by providing options and keeping the client focused on working toward his or her goals, rather than telling the client what the goals should be or the right way to get there. Almost any caring therapist, regardless of theoretical orientation, will start sessions by asking the client how things have gone since the last meeting. The anticipation of such reporting may cause clients to go through life, between therapy sessions, with more conscious attention to their actions and feelings than they otherwise would so that they can give a full report. Such attention leads them to think more consciously, fully, and constructively about their problems, which enhances their motivation to improve and may also lead to new insights about how to improve. Such reporting may also make the client aware of progress, and progress engenders a desire for more progress.

692

A Final Comment

Through most of this book our main concern has been with normal, healthy, adaptive human behavior. It is perhaps fitting, though, and certainly humbling, to end on this note concerning psychotherapy:

We are social animals who need positive regard from other people in order to function well, but sometimes that regard is lacking. We are thinking animals, but sometimes our emotions and disappointments get in the way of our thinking. We are self-motivated and self-directed creatures, but sometimes we lose our motivation and direction. In these cases, a supportive, hope-inspiring, and motivating psychotherapist can help. The therapist helps not by solving our problems for us, but by providing a context in which we can solve them ourselves.

SECTION REVIEW

Psychotherapy’s effectiveness, and reasons for its effectiveness, have been widely researched.

Determining the Effectiveness of Psychotherapy

- Many controlled experiments, comparing patients in psychotherapy with comparable others not in psychotherapy, have shown that psychotherapy helps.

- Research also indicates that no form of therapy is more effective overall than any other, perhaps because different therapies are more similar in practice than in theory.

- Some therapies are better than others for particular situations, however. For example, behavioral exposure therapy is more effective than other treatments for specific phobias.

The Role of Common Factors in Therapy Outcome

- Common factors, shared by all standard psychotherapies, may account for much of the effectiveness of psychotherapy. These include support, hope, and motivation.

- Support (acceptance, empathy, and encouragement) helps to build the client’s confidence. Research suggests that support, in and of itself, has considerable therapeutic value.

- Hope comes in part from faith in the process, bolstered by the therapist’s own faith in it. People who believe they will get better have a greater chance of getting better.

- The support, hope, and regular reporting of experiences in therapy help to motivate clients toward self-improvement.