1.1 Three Fundamental Ideas for Psychology: A Historical Overview

The founding of psychology as a formal, recognized, scientific discipline is commonly dated to 1879, when Wilhelm Wundt opened the first university-based psychology laboratory in Leipzig, Germany. At about that same time, Wundt also authored the first psychology textbook and began mentoring psychology’s first official graduate students. The first people to earn Ph.D. degrees in psychology were Wundt’s students.

But the roots of psychology predate Wundt. They were developed by people who called themselves philosophers, physicists, physiologists, and naturalists. In this section, we examine three fundamental ideas of psychology, all of which were conceived of and debated before psychology was recognized as a scientific discipline. Briefly, the ideas are these:

5

- Behavior and mental experiences have physical causes that can be studied scientifically.

- The way people behave, think, and feel is modified over time by their experiences in their environment.

- The body’s machinery, which produces behavior and mental experiences, is a product of evolution by natural selection.

The Idea of Physical Causation of Behavior

Before a science of psychology could emerge, people had to conceive of and accept the idea that questions about human behavior and the mind can, in principle, be answered scientifically. Seeds for this idea can be found in some writings of the ancient Greeks, who speculated about the senses, human intellect, and the physical basis of the mind in ways that seem remarkably modern. But these seeds lay dormant through the Middle Ages and did not begin to sprout again until the fifteenth century (the Renaissance) or to take firm hold until the eighteenth century (the Enlightenment).

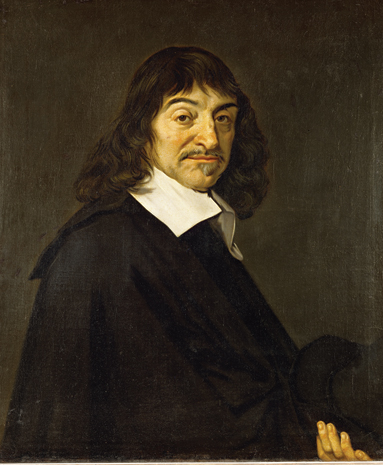

Until the eighteenth century, philosophy was tightly bound to and constrained by religion. The church maintained that each human being consists of two distinct but intimately conjoined entities, a material body and an immaterial soul—a view referred to today as dualism. The body is part of the natural world and can be studied scientifically, just as inanimate matter can be studied. The soul, in contrast, is a supernatural entity that operates according to its own free will, not natural law, and therefore cannot be studied scientifically. This was the accepted religious doctrine, which—at least in most of Europe—could not be challenged publicly without risk of a charge of heresy and possible death. Yet the doctrine left some room for play, and one who played dangerously near the limits was the great French mathematician, physiologist, and philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650).

Descartes’ Version of Dualism: Focus on the Body

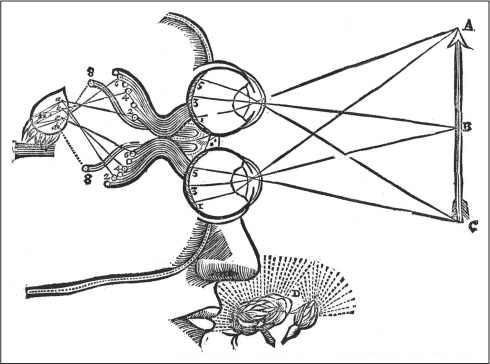

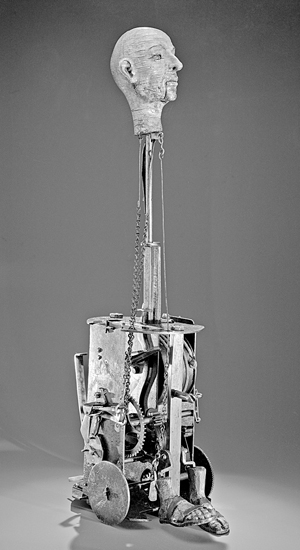

Before Descartes, most dualists assigned the interesting qualities of the human being to the soul. The soul was deemed responsible for the body’s heat, for its ability to move, for life itself. In Treatise of Man (1637/1972), and even more explicitly in The Passions of the Soul (1649/1985), Descartes challenged this view. He was familiar with research on the flow of blood and began to regard the body as an intricate, complex machine that generates its own heat and is capable of moving, even without the influence of the soul. Although little was known about the nervous system in his time, Descartes’ conception of the mechanical control of movement resembles our modern understanding of reflexes, which are involuntary responses to stimuli (see Figure 1.1).

2

What was Descartes’ version of dualism? How did it help pave the way for a science of psychology?

Descartes believed that even quite complex behaviors can occur through purely mechanical means, without involvement of the soul. Consistent with church doctrine, he contended that nonhuman animals do not have souls, and he pointed out a logical implication of this contention: Any activity performed by humans that is qualitatively no different from the behavior of a nonhuman animal can, in theory, occur without the soul. If my dog (who can do some wondrous things) is just a machine, then a good deal of what I do—such as eating, drinking, sleeping, running, panting, and occasionally going in circles—might occur purely mechanically as well.

6

In Descartes’ view, the one essential ability that we have but dogs do not is thought, which Descartes defined as conscious deliberation and judgment. Whereas previous philosophers ascribed many functions to the soul, Descartes ascribed just one—thought. But even in his discussion of thought, Descartes tended to focus on the body’s machinery. To be useful, thought must be responsive to the sensory input channeled into the body through the eyes, ears, and other sense organs, and it must be capable of directing the body’s movements by acting on the muscles.

How can the thinking soul interact with the physical machine—the sense organs, muscles, and other parts of the body? Descartes suggested that the soul, though not physical, acts on the body at a particular physical location. Its place of action is a small organ (now known as the pineal body) buried between the two hemispheres (halves) of the brain (see Figure 1.2).

Thread-like structures, which we now call nerves or neurons, bring sensory information by physical means into the brain, where the soul receives the information and, by nonphysical means, thinks about it. On the basis of those thoughts, the soul then wills movements to occur and executes its will by triggering physical actions in nerves that, in turn, act on muscles. Descartes’ dualism, with its heavy emphasis on the body, certainly helped open the door for a science of psychology.

3

What reasons can you think of for why Descartes’ theory, despite its intuitive appeal, was unsuitable for a complete psychology?

Descartes’ theory is popular among nonscientists even today because it acknowledges the roles of sense organs, nerves, and muscles in behavior without violating people’s religious beliefs or intuitive feelings that conscious thought occurs on a nonphysical plane. But it has serious limitations, both as a philosophy and as a foundation for a science of psychology. As a philosophy, it stumbles on the question of how a nonmaterial entity (the soul) can have a material effect (movement of the body), or how the body can follow natural law and yet be moved by a soul that does not (Campbell, 1970). As a foundation for psychology, the theory sets strict limits, which few psychologists would accept today, on what can and cannot be understood scientifically. The whole realm of thought, and all behaviors that are guided by thought, are out of bounds for scientific analysis if they are the products of a willful soul.

Thomas Hobbes and the Philosophy of Materialism

4

How did Hobbes’s materialism help lay the groundwork for a science of psychology?

At about the same time that Descartes was developing his machine-oriented version of dualism, an English philosopher named Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) was going much further. In his book Leviathan, and in a shorter work called Human Nature, Hobbes argued that spirit, or soul, is a meaningless concept and that nothing exists but matter and energy, a philosophy now known as materialism. In Hobbes’s view, all human behavior, including the seemingly voluntary choices we make, can in theory be understood in terms of physical processes in the body, especially the brain. Conscious thought, he maintained, is purely a product of the brain’s machinery and therefore subject to natural law. This philosophy places no theoretical limit on what psychologists might study scientifically. Most of Hobbes’s work was directed toward the implications of materialism for politics and government, but his ideas helped inspire, in England, a school of thought about the mind known as empiricism, which we will discuss below.

7

Nineteenth-Century Physiology: Learning About the Machine

The idea that the body, including the brain, is a machine, amenable to scientific study, helped to promote the science of physiology—the study of the body’s machinery. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, considerable progress had been made in this endeavor, and during that century discoveries were made about the nervous system that contributed significantly to the origins of scientific psychology.

Increased Understanding of Reflexes One especially important development for the later emergence of psychology was an increased understanding of reflexes. The basic arrangement of the nervous system—consisting of a central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and peripheral nerves that connect the central nervous system to sense organs and muscles—was well understood by the beginning of the nineteenth century. In 1822, the French physiologist François Magendie demonstrated that nerves entering the spinal cord contain two separate pathways: one for carrying messages into the central nervous system from the skin’s sensory receptors and one for carrying messages out to operate muscles. Through experiments with animals, scientists began to learn about the neural connections that underlie simple reflexes, such as the automatic withdrawal response to a pinprick. They also found that certain brain areas, when active, could either enhance or inhibit such reflexes.

5

How did the nineteenth-century understanding of the nervous system inspire a theory of behavior called reflexology?

Some of these physiologists began to suggest that all human behavior occurs through reflexes—that even so-called voluntary actions are actually complex reflexes involving higher parts of the brain. One of the most eloquent proponents of this view, known as reflexology, was the Russian physiologist I. M. Sechenov. In his monograph Reflexes of the Brain, Sechenov (1863/1935) argued that every human action, “[b]e it a child laughing at the sight of toys, or…Newton enunciating universal laws and writing them on paper,” can in theory be understood as a reflex. All human actions, he claimed, are initiated by stimuli in the environment. The stimuli act on a person’s sensory receptors, setting in motion a chain of events in the nervous system that culminates in the muscle movements that constitute the action. Sechenov’s work inspired another Russian physiologist, Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936), whose work on reflexes (discussed in Chapter 4) played a crucial role in the development of a scientific psychology.

6

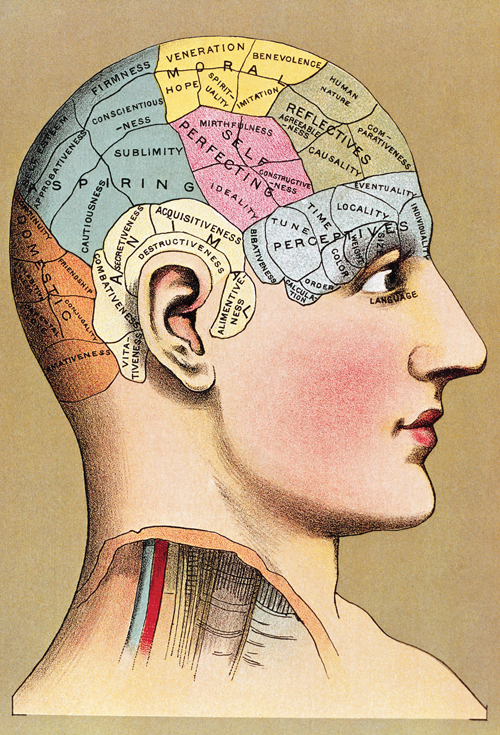

How did discoveries of localization of function in the brain help establish the idea that the mind can be studied scientifically?

The Concept of Localization of Function in the Brain Another important advance in nineteenth-century physiology was the concept of localization of function, the idea that specific parts of the brain serve specific functions in the production of mental experience and behavior. In Germany, Johannes Müller (1838/1965) proposed that the different qualities of sensory experience come about because the nerves from different sense organs excite different parts of the brain. Thus we experience vision when one part of the brain is active, hearing when another part is active, and so on. In France, Pierre Flourens (1824/1965) performed experiments with animals showing that damage to different parts of the brain produces different kinds of deficits in animals’ abilities to move. And Paul Broca (1861/1965), also in France, published evidence that people who suffer injury to a very specific area of the brain’s left hemisphere lose the ability to speak but do not lose other mental abilities. All such evidence about the relationships between mind and brain helped to lay the groundwork for a scientific psychology because it gave substance to the idea of a material basis for mental processes.

8

The Idea That the Mind and Behavior Are Shaped by Experience

Besides helping to inspire research in physiology, the materialist philosophy of seventeenth-century England led quite directly to a school of thought about the mind known as British empiricism, carried on by such British philosophers as John Locke (1632–1704), David Hartley (1705–1759), James Mill (1773–1836), and John Stuart Mill (1806–1873). Empiricism, in this context, refers to the idea that human knowledge and thought derive ultimately from sensory experience (vision, hearing, touch, and so forth). If we are machines, we are machines that learn. Our senses provide the input that allows us to acquire knowledge of the world around us, and this knowledge allows us to think about that world and behave adaptively within it. The essence of empiricist philosophy is poetically expressed in the following often-quoted passage from Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690/1975, p. 104):

9

Let us suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper, void of all characters, without any ideas; how comes it to be furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store, which the busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it, with an almost endless variety? Whence has it all the materials of reason and knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from experience. In that, all our knowledge is founded; and from that it ultimately derives itself.

Locke viewed a child’s mind as a tabula rasa, or blank slate, and believed that experience serves as the chalk that writes on and fills the slate. The human brain has limitations, of course—we can’t detect objects using echolocation as bats and dolphins can, for instance. But Locke argued that, outside of these extremes, children are born with no dispositions to make some types of learning easier than others, for example, or preferences to influence how they learn and develop. From this perspective, there is no “human nature” other than an ability to adapt one’s behavior to the demands of the environment.

The Empiricist Concept of Association by Contiguity

7

How would you explain the origin of complex ideas and thoughts according to British empiricism? What role did the law of association by contiguity play in this philosophy?

In keeping with materialist philosophy, Locke and the other British empiricists argued that thoughts are not products of free will but rather reflections of a person’s experiences in the physical and social environment. All the contents of the mind derive from the environment and bear direct relationship to that environment. According to the empiricists, the fundamental units of the mind are elementary ideas that derive directly from sensory experiences and become linked together, in lawful ways, to form complex ideas and thoughts.

The most basic operating principle of the mind’s machinery, according to the empiricists, is the law of association by contiguity, an idea originally proposed by Aristotle in the fourth century BCE. Contiguity refers to closeness in space or time, and the law of association by contiguity can be stated as follows: If a person experiences two environmental events (stimuli, or sensations) at the same time or one right after the other (contiguously), those two events will become associated (bound together) in the person’s mind such that the thought of one event will, in the future, tend to elicit the thought of the other.

As a simple illustration, consider a child’s experiences when seeing and biting into an apple. In doing so, the child receives a set of sensations that produce in her mind such elementary ideas as red color, spherical shape, and sweet, tart taste. The child may also, at the same time, hear the sound apple emanating from the vocal cords of a nearby adult. Because all these sensations are experienced together, they become associated in the child’s mind. Together, they form the complex idea “apple.” Because of association by contiguity, the thought of any of the sensory qualities of the apple will tend to call forth the thought of all the apple’s other sensory qualities. Thus, when the child hears apple, she will think of the red color, the spherical shape, and the sweet, tart taste. Or, when the child sees an apple, she will think of the sound apple and imagine the taste.

The empiricists contended that even their own most complex philosophical ponderings could, in theory, be understood as amalgams of elementary ideas that became linked together in their minds as a result of contiguities in their experiences. John Stuart Mill (1843/1875) referred to this sort of analysis of the mind as mental chemistry. Complex ideas and thoughts are formed from combinations of elementary ideas, much as chemical compounds are formed from combinations of chemical elements.

10

8

How would you describe the influence that empiricist philosophy has had on psychology?

As you will discover in Chapters 4 and 9, the law of association by contiguity is still regarded as a fundamental principle of learning and memory. More broadly, most of psychology—throughout its history—has been devoted to the study of the effects of people’s environmental experiences on their thoughts, feelings, and behavior. The impact of empiricist philosophy on psychology has been enormous.

The Nativist Response to Empiricism

9

Why is the ability to learn dependent on inborn knowledge? In Kant’s nativist philosophy, what is the distinction between a priori knowledge and a posteriori knowledge?

For every philosophy that contains part of the truth, there is an opposite philosophy that contains another part of it. The opposite of empiricism is nativism, the view that the most basic forms of human knowledge and the basic operating characteristics of the mind, which provide the foundation for human nature, are native to the human mind—that is, are inborn and do not have to be acquired from experience.

Take a sheet of white paper and present it with all the learning experiences that a normal human child might encounter (a suggestion made by Ornstein, 1991). The paper will learn nothing. Talk to it, sing to it, give it apples and oranges, take it for trips in the country, hug it and kiss it; it will learn nothing about language, music, fruit, nature, or love. To learn anything, any entity must contain some initial machinery already built into it. At a minimum, that machinery must include an ability to sense some aspects of the environment, some means of interpreting and recording those sensations, some rules for storing and combining those sensory records, and some rules for recalling them when needed. The mind, contrary to Locke’s poetic assertion, must come with some initial furnishings in order for it to be furnished further through experience.

While empiricist philosophy flourished in England, nativist philosophy took root in Germany, led by such thinkers as Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz (16461716) and Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1965), Kant distinguished between a priori knowledge, which is built into the human brain and does not have to be learned, and a posteriori knowledge, which one gains from experience in the environment. Without the first, argued the nativists, a person could not acquire the second. As an illustration, Kant referred to a child’s learning of language. The specific words and grammar that the child acquires are a posteriori knowledge, but the child’s ability to learn a language at all depends on a priori knowledge. The latter includes built-in rules about what to attend to and how to store and organize the linguistic sounds that are heard, in ways that allow the child eventually to make sense of the sounds. Kant also argued that to make any sense of the physical world, the child must already have certain fundamental physical concepts, such as the concepts of space and time, built into his or her mind. Without such built-in concepts, a child would have no capacity for seeing an apple as spherical or for detecting the temporal contiguity of two events.

The Idea That the Machinery of Behavior and Mind Evolved Through Natural Selection

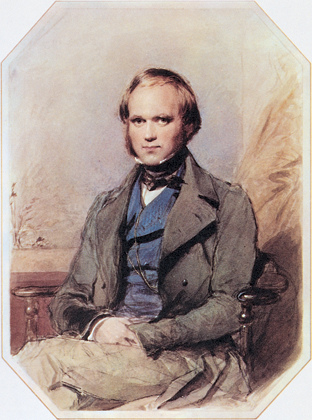

Kant understood that the human mind has some innate furnishings, but he had no scientific explanation of how those furnishings could have been built or why they function as they do. That understanding finally came in 1859 when the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) published The Origin of Species, a book that was destined to revolutionize biology, mark a new age in philosophy, and provide, along with the developments in physiology, a biological grounding for psychology.

11

Natural Selection and the Analysis of the Functions of Behavior

10

How did Darwin’s theory of natural selection offer a scientific foundation for explaining behavior by describing its functions? How did it provide a basis for understanding the origin of a priori knowledge?

Darwin’s fundamental idea (explained much more fully in Chapter 3) was that living things evolve gradually, over generations, by a process of natural selection. Those individuals whose inherited characteristics are well adapted to their local environment are more likely to survive and reproduce than are other, less well-adapted individuals. At each generation, random changes in the hereditary material produce variations in offspring, and those variations that improve the chance of survival and reproduction are passed from generation to generation in increasing numbers.

Because of natural selection, species of plants and animals change gradually over time in ways that allow them to meet the changing demands of their environments. Because of evolution, the innate characteristics of any given species of plant or animal can be examined for the functions they serve in helping the individuals to survive and reproduce. For example, to understand why finches have stout beaks and warblers have slender beaks, one must know what foods the birds eat and how they use their beaks to obtain those foods. The same principle that applies to anatomy applies to behavior. Through natural selection, living things have acquired tendencies to behave in ways that promote their survival and reproduction. A key word here is function. While physiologists were examining the neural mechanisms of behavior, and empiricist philosophers were analyzing lawful relationships between behavior and the environment, Darwin was studying the functions of behavior—the ways in which an organism’s behavior helps it to survive and reproduce.

Application of Darwin’s Ideas to Psychology

In The Origin of Species, Darwin discussed only plants and nonhuman animals, but in later writings he made it clear that he viewed humans as no exception. We humans also evolved through natural selection, and our anatomy and behavior can be analyzed in the same ways as those of other living things. In fact, Darwin can be thought of as the first evolutionary psychologist, writing in 1859,“In the distant future…psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation. Light will be thrown on the origins of man and his history” (p. 488).

In a book titled The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Darwin (1872/1965) illustrated how evolutionary thinking can contribute to a scientific understanding of human behavior. He argued that the basic forms of human emotional expressions (such as laughing and crying) are inherited, as are those of other animals, and may have evolved because the ability to communicate one’s emotions or intentions improves one’s chances of survival. Darwin’s work provided psychology with a scientific way of thinking about all the inborn universal tendencies that constitute human nature. The inherited mechanisms underlying human emotions, drives, perception, learning, and reasoning came about gradually because they promoted the survival and reproduction of our ancestors. One approach to understanding such characteristics is to analyze their evolutionary functions—the specific ways in which they promote survival and reproduction.

If Kant had been privy to Darwin’s insight, he would likely have said that the inherent furnishings of the mind, which make it possible for children to learn language, to learn about the physical world, to experience human drives and emotions, and, more generally, to behave as human beings and not as blank sheets of paper, came about through the process of natural selection, which gradually built all these capacities into the brain’s machinery. Darwin, perhaps more than anyone else, helped convince the intellectual world that we humans, despite our pretensions, are part of the natural world and can be understood through the methods of science. In this way he helped make the world ripe for psychology.

11

How can you use the section review at the end of each major section of each chapter to guide your thoughts and review before going on to the next section?

We have now reached the end of the first section of the chapter, and, before moving on, we want to point out a second feature of the book that is designed to help you study it. At the end of each major section of each chapter is a section review chart that summarizes the section’s main ideas. The chart is organized hierarchically: The main idea or topic of the section is at the top, the sub-ideas or subtopics are at the next level down, and specific facts and lines of evidence pertaining to each sub-idea or subtopic fill the lower parts. A good way to review, before going on, is to read each item in the chart and think about it. Start at the top and think about the main idea or purpose of the whole section. How would you explain it to another person? Then go down each column, one by one; think about how the idea or topic heading the column pertains to the larger idea or topic above it and how it is supported or elaborated upon by the more specific statements below it. If you are unsure of the meaning of any item in the chart, or can’t elaborate on that item in a meaningful way, you may want to read the relevant part of the chapter again before moving on. Another way to review is to look back at the focus questions in the margins and make sure you can answer each of them.

12

SECTION REVIEW

Psychology—the science of behavior and the mind—rests on prior intellectual developments.

Physical Causation of Behavior

- Descartes’ dualism placed more emphasis on the role of the body than had previous versions of dualism. Hobbes’s materialism held that behavior is completely a product of the body and thus physically caused.

- To the degree that behavior and the mind have a physical basis, they are open to study just like the rest of the natural world.

- Nineteenth-century physiological studies of reflexes and localization of function in the brain demonstrated the applicability of science to mental processes and behavior.

The Role of Experience

- The British empiricists claimed that all thought and knowledge are rooted in sensory experience.

- Empiricists used the law of association by contiguity to explain how sensory experiences can combine to form complex thoughts.

- In contrast to empiricism, nativism asserts that some knowledge is innate and that such knowledge provides the foundation for human nature, including the human abilities to learn.

The Evolutionary Basis of Mind and Behavior

- Darwin proposed that natural selection underlies the evolution of behavioral tendencies (along with anatomical characteristics) that promote survival and reproduction.

- Darwin’s thinking led to a focus on the functions of behavior.

- Natural selection also offered a scientific foundation for nativist views of the mind.