3.6 Evolutionary Analyses of Mating Patterns

From an evolutionary perspective, no class of behavior is more important than mating. Mating is the means by which all sexually reproducing animals get their genes into the next generation. Mating is also interesting because it is the most basic form of social behavior. Sex is the foundation of society. Were it not necessary for female and male to come together to reproduce, members of a species could, in theory, go through life completely oblivious to one another.

86

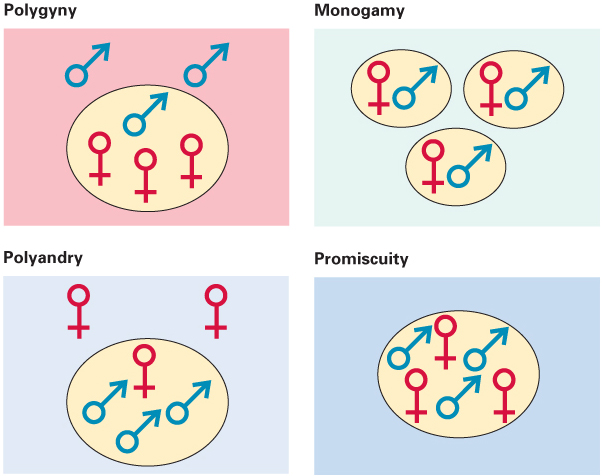

Countless varieties of male-female arrangements for sexual reproduction have evolved in different species of animals. One way to classify them is according to the number of partners a male or female typically mates with over a given period of time, such as a breeding season. Four broad classes are generally recognized: polygyny[pe-lĭj’-e-nē’], in which one male mates with more than one female; polyandry[pŏl’-ē-ăn’-drē], in which one female mates with more than one male; monogamy[mŏ-nŏg’-e-mē], in which one male mates with one female; and promiscuity[prŏm’-i-skyōō’-Ĭ-tē], in which members of a group consisting of more than one male and more than one female mate with one another (Shuster & Wade, 2009). (These terms are easy to remember if you know that poly- means “many”; mono-, “one”; -gyn, “female”; and -andr, “male.” Thus, for example, polyandry literally means “many males.”) As illustrated in Figure 3.19, a feature of both polygyny and polyandry is that some individuals are necessarily deprived of a mating opportunity—a state of affairs associated with considerable conflict.

A Theory Relating Mating Patterns to Parental Investment

33

What is Trivers’s theory of parental investment?

In a now-classic article, Robert Trivers (1972) outlined a theory relating courtship and mating patterns to sex differences in amount of parental investment. Parental investment can be defined roughly as the time, energy, and risk to survival that are involved in producing, feeding, and otherwise caring for each offspring. More precisely, Trivers defined it as the loss of future reproductive capacity that results from the adult’s production and nurturance of any given offspring. Every offspring in a sexually reproducing species has two parents, one of each sex, but the amount of parental investment from the two is usually not equal. The essence of Trivers’s theory is this: In general, for species in which parental investment is unequal, the more parentally invested sex will be (a) more vigorously competed for than the other and (b) more discriminating than the other when choosing mates.

To illustrate and elaborate on this theory—and to see how it is supported by cross-species comparisons focusing on analogies—let us apply it to each of the four general classes of mating patterns.

87

Polygyny Is Related to High Female and Low Male Parental Investment

34

Based on Trivers’s theory of parental investment, why does high investment by the female lead to (a) polygyny, (b) large size of males, and (c) high selectivity in the female’s choice of mate?

Most species of mammals are polygynous, and Trivers’s theory helps explain why. Mammalian reproductive physiology is such that the female necessarily invests a great deal in the offspring she bears. The young must first develop within her body and then must obtain nourishment from her in the form of milk. Because of the female’s high investment, the number of offspring she can produce in a breeding season or a lifetime is limited. A human female’s gestation and lactation periods are such that she can have, at most, approximately one infant per year. She can produce no more than that regardless of the number of different males with whom she mates.

Things are different for the male. His involvement with offspring is, at minimum, simply the production of sperm cells and the act of copulation. These require little time and energy, so his maximum reproductive potential is limited not by parental investment but by the number of fertile females with which he mates. A male who mates with 20 females can in theory produce 20 offspring a year. When the evolutionary advantage in mating with multiple partners is greater for males than for females, a pattern evolves in which males compete with one another to mate with as many females as they can.

Among mammals, males’ competition for females often involves one-on-one battles, which the larger and stronger combatant most often wins. This leads to a selective advantage for increased size and strength in males, up to some maximum beyond which the size advantage in obtaining mates is outweighed by disadvantages, such as difficulty in finding sufficient food to support the large size. In general, the more polygynous a species, the greater is the average size difference between males and females. An extreme example is the elephant seal. Males of this species fight one another, sometimes to the death, for mating rights to groups averaging about 50 females, and the males outweigh females several-fold (Hoelzel et al., 1999). In the evolution of elephant seals, those males whose genes made them large, strong, and ferocious enough to defeat other males sent many copies of their genes on to the next generation, while their weaker or less aggressive opponents sent few or none.

For the same reason that the female mammal usually has less evolutionary incentive than the male to mate with many individuals, she has more incentive to be discriminating in her choice of mate (Trivers, 1972). Because she invests so much, risking her life and decreasing her future reproductive potential whenever she becomes pregnant, her genetic interests lie in producing offspring that will have the highest possible chance to survive and reproduce. To the degree that the male affects the young, either through his genes or through other resources he provides, females would be expected to select males whose contribution will be most beneficial. In elephant seals, it is presumably to the female’s evolutionary advantage to mate with the winner of battles. The male victor’s genes increase the chance that the female’s sons will win battles in the future and produce many young themselves.

88

Polyandry Is Related to High Male and Low Female Parental Investment

35

What conditions promote the evolution of polyandry? How do sex differences within polyandrous species support Trivers’s theory?

Polyandry is not the primary mating pattern for any species of mammal, but it is for some species of fishes and birds (Andersson, 2005). Polyandry is more likely to evolve in egg-laying species than in mammals because a smaller proportion of an egg layer’s reproductive cycle is tied to the female’s body. Once the eggs are laid, they can be cared for by either parent, and, depending on other conditions, evolution can lead to greater male than female parental investment. Polyandry seems to come about in cases where the female can produce more eggs during a single breeding season than either she alone or she and one male can care for (Andersson, 2005). Her best strategy then becomes that of mating with multiple males and leaving each batch of fertilized eggs with the father, who becomes the main or sole caretaker.

Consistent with Trivers’s theory, females of polyandrous species are the more active and aggressive courters, and they have evolved to be larger, stronger, and in some cases more brightly colored than the males (Berglund & Rosenqvist, 2001). An example is the spotted sandpiper, a common fresh water shorebird. A female spotted sandpiper can lay up to three clutches of eggs in rapid succession, each cared for by a different male that has mated with her (Oring, 1995). At the beginning of the breeding season, the females—which outweigh the males by about 20 percent and have somewhat more conspicuous spots—stake out territories where they actively court males and drive out other females.

Monogamy Is Related to Equivalent Male and Female Parental Investment

36

What conditions promote the evolution of monogamy? Why are sex differences in size and strength generally lacking in monogamous species?

According to Trivers’s theory, when the two sexes make approximately equal investments in their young, their degree of competition for mates will also be approximately equal, and monogamy will prevail. Equal parental investment is most likely to come about when conditions make it impossible for a single adult to raise the young but quite possible for two to raise them. Under these circumstances, if either parent leaves, the young fail to survive, so natural selection favors genes that lead parents to stay together and care for the young together. Because neither sex is much more likely than the other to fight over mates, there is little or no natural selection for sex differences in size and strength, and, in general, males and females of monogamous species are nearly identical in these characteristics.

89

Consistent with the view that monogamy arises from the need for more than one adult to care for offspring, over 90 percent of bird species are predominantly monogamous (Cézilly & Zayan, 2000; Lack, 1968). Among most species of birds, unlike most mammals, a single parent would usually not be able to raise the young. Birds must incubate and protect their eggs until they hatch, then must guard the hatchlings and fetch food for them until they can fly. One parent alone cannot simultaneously guard the nest and leave it to get food, but two together can. Among mammals, monogamy has arisen in some species that are like birds in the sense that their young must be given food other than milk, of a type that the male can provide. The best-known examples are certain carnivores, including foxes and coyotes (Malcolm, 1985). Young carnivores must be fed meat until they have acquired the necessary strength, agility, and skills to hunt on their own, and two parents are much better than one at accomplishing this task. Monogamy also occurs in several species of rodents, where the male may play a crucial role in protecting the young from predators while the mother forages (Sommer, 2000), and some South American monkeys (that is, owl, Goeldi’s, and titi monkeys), where the father actually engages in more child care than the mother (Schradin et al., 2003).

37

For what evolutionary reasons might monogamously mated females and males sometimes copulate with partners other than their mates?

With modern DNA techniques to determine paternity, researchers have learned that social monogamy (the faithful pairing of female and male for raising young) does not necessarily imply sexual monogamy (fidelity in copulation between that female and male). Researchers commonly find that between 5 and 35 percent of offspring in socially monogamous birds are sired by a neighboring male rather than by the male at the nest (Birkhead & Moller, 1992); for one species, the superb fairy wren, that average is 75 percent (Mulder, 1994).

Why does such extra-mate copulation occur? From the female’s evolutionary perspective, copulation with a male that is genetically superior to her own mate (as manifested in song and feathers) results in genetically superior young, and copulation with any additional male increases the chance that all her eggs will be fertilized by viable sperm (Zeh & Zeh, 2001). For the male, evolutionary advantage rests in driving neighboring males away from his own mate whenever possible and in copulating with neighboring females whenever possible. Genes that build brain mechanisms that promote such behaviors are passed along to more offspring than are genes that do not.

Promiscuity Is Related to Investment in the Group

38

What appear to be the evolutionary advantages of promiscuity for chimpanzees and bonobos? In what ways is promiscuity more fully developed for bonobos than for chimpanzees?

Among the clearest examples of promiscuous species are chimpanzees and bonobos, which happen to be our two closest animal relatives (refer back to Figure 3.15). Bonobos are similar in appearance to chimpanzees but are rarer and have only recently been studied in the wild. The basic social structure of both species is the troop, which consists usually of two to three dozen adults of both sexes and their offspring. When the female is ovulating, she develops on her rump a prominent pink swelling, which she actively displays to advertise her condition. During the time of this swelling, which lasts about 1 week in chimps and 3 weeks in bonobos, she is likely to mate with most of the adult males of the colony, though she may actively choose to mate with some more often than with others, especially at the point in her cycle when she is most fertile (Goodall, 1986; Kano, 1992; Stumpf & Boesch, 2006).

Promiscuity has apparently evolved in these ape species because it permits a group of adult males and females to live together in relative harmony, without too much fighting over who mates with whom. A related advantage, from the female’s perspective, is paternity confusion (Hrdy, 1981, 2009). Among many species of primates, males kill young that are not their own, and such behavior has been observed in chimpanzees when a female migrates into a troop bringing with her an infant that was sired elsewhere (Wrangham, 1993). Because almost any chimp or bonobo male in the colony could be the father of any infant born within the troop, each male’s evolutionary interest lies not in attacking the young but in helping to protect and care for the group as a whole.

90

Promiscuity seems to be more fully developed in bonobos than in chimps. Male chimps sometimes use force to monopolize the sexual activity of a female throughout her ovulatory cycle or during the period of peak receptivity (Goodall, 1986; Wrangham, 1993), but this does not appear to occur among bonobos (Hohmann & Fruth, 2003; Wrangham, 1993). In fact, among bonobos sex appears to be more a reducer of aggression than a cause of it (Parish & de Waal, 2000; Wrangham, 1993). Unlike any other apes, female bonobos copulate at all times of their reproductive cycle, not just near the time of ovulation. In addition to their frequent heterosexual activity, bonobos of the same sex often rub their genitals together, and genital stimulation of all types occurs most often following conflict and in situations that could potentially elicit conflict, such as when a favorite food is discovered (Hohmann & Fruth, 2000; Parish, 1996). Field studies suggest that bonobos are the most peaceful of primates and that their frequent promiscuous sexual activity helps keep them that way (de Waal, 2005; Kano, 1992).

What About Human Mating Patterns?

A Largely Monogamous, Partly Polygynous Species

39

What evidence suggests that humans evolved as a partly monogamous, partly polygynous species? How is this consistent with Trivers’s parental investment theory?

When we apply the same criteria that are used to classify the mating systems of other species, we find that humans fall on the boundary between monogamy and polygyny (Dewsbury, 1988). In no culture are human beings as sexually promiscuous as are our closest ape relatives, the chimpanzees and bonobos. In every culture, people form long-term mating bonds, which are usually legitimized through some sort of culturally recognized marriage contract. Anthropologists have found that the great majority of non-Western cultures, where Western influence has not made polygyny illegal, practice a mixture of monogamy and polygyny (Marlowe, 2000; Murdock, 1981). In such cultures, a few men, who have sufficient wealth or status, have two or more wives, while the great majority of men have one wife and a few have none. Thus, even in cultures that permit and idealize polygyny, most marriages are monogamous.

91

Human children, more so than the young of any other primates, require an extended period of care before they can play full adult roles in activities such as food gathering. Cross-cultural research shows that in every culture mothers provide most of the direct physical care of children, but fathers contribute in various ways, which is rare among mammals. Humans are among the 5 percent of mammals in which the male provides some support to his offspring (Clutton-Brock, 1991). In many cultures—especially in hunter-gatherer cultures—fathers share to some degree in the physical care of their offspring (Marlowe, 2000), and in nearly all cultures fathers provide indirect care in the form of food and other material provisions. In fact, in 77 percent of the cultures for which data are available, fathers provide more of the provisions for young than do mothers (Marlowe, 2000). Taking both direct and indirect care into account, we are a species in which fathers typically lag somewhat behind mothers, but not greatly behind them, in degree of parental investment. This, in line with Trivers’s parental investment theory, is consistent with our being a primarily monogamous but moderately polygynous species.

The moderate size difference between men and women is also consistent with this conclusion (Dewsbury, 1988). The average size difference between males and females in humans is nowhere near that observed in highly polygynous species, such as elephant seals and gorillas, but is greater than that observed in monogamous species.

Another clue to Homo sapiens’ prehistorical mating patterns comes from a comparative analysis of the different types of white blood cells—which play an important role in the immune system—between humans and other primates with different types of mating systems (Nunn et al., 2000). Sexually transmitted diseases can be a problem not just for humans but for other species as well, and the more sex partners one has, the stronger one’s immune system needs to be to combat infection. Nunn and his colleagues found that sexually promiscuous species, such as chimpanzees and bonobos, had more types of white blood cells than monogamous species, such as owl monkeys. Humans’ immune system was between those of the polygymous, harem-based gorilla and the monogamous gibbon (a lesser ape). This suggests that the marginally monogamous/marginally polygymous relationships that characterize modern and historic humans also characterized our species’ prehistoric ancestors.

Roles of Emotions in Human Mating Systems

40

From an evolutionary perspective, what are the functions of romantic love and sexual jealousy, and how is this supported by cross-species comparisons? How is sexual unfaithfulness explained?

Our biological equipment that predisposes us for mating bonds includes brain mechanisms that promote the twin emotions of romantic love and sexual jealousy. These emotions are found in people of every culture that has been studied (Buss, 2000b; Fisher, 2004). People everywhere develop strong emotional ties to those toward whom they are sexually drawn. The predominant feeling is a need to be regularly near the other person. People everywhere also feel intensely jealous when “their” mates appear to be sexually drawn to others. While love tends to create mating bonds, jealousy tends to preserve such bonds by motivating each member of a mated pair to act in ways designed to prevent the other from having an affair with someone else.

Other animals that form long-term mating bonds show evidence of emotions that are functionally similar to human love and jealousy (for example, Lazarus et al., 2004). In this sense, we are more like monogamous birds than we are like our closest ape relatives. The similarities between humans and birds in sexual love and jealousy are clearly analogies, not homologies (Lorenz, 1974). These evolved separately in humans and birds as means to create and preserve mating bonds that are sufficiently strong and durable to enable biparental care of offspring. Chimpanzees and bonobos (especially the latter) can engage in open, promiscuous sex with little emotional consequence because they have not evolved strong emotions of sexual love and jealousy, but humans and monogamous birds cannot. The difference ultimately has to do with species differences in their offsprings’ need for care from both parents.

92

At the same time that love and jealousy tend to promote bonding, lust (another product of evolution) tends to motivate both men and women to engage surreptitiously in sex outside of such bonds. In this sense we are like those socially monogamous birds that are sexually unfaithful. A man who can inseminate women beyond his wife may send more copies of his genes into the next generation than a completely faithful man. A woman who has sex with men other than her husband may also benefit evolutionarily. Such escapades may (a) increase her chances of conception by serving as a hedge against the possibility that her husband’s sperm are not viable or are genetically incompatible with her eggs; (b) increase the evolutionary fitness of her offspring if she mates with a man whose genes are evolutionarily superior to those of her husband; and/or (c) result in provisions from more than one man (Hrdy, 2009). And so the human soap opera continues, much like that of the superb fairy wren, though not to such an extreme. Studies involving DNA testing, in cultures ranging from hunter-gatherer groups to modern Western societies, suggest that somewhere between 2 and 10 percent of children in socially monogamous families are sired by someone other than the mother’s husband (Marlowe, 2000).

What about polyandry—one woman and several men? Do humans ever engage in it? Not typically, but it is not unheard of. Polyandry occurs in some cultures when one man cannot secure enough resources to support a wife and her children. When it does happen, usually two brothers will share a wife. In this way, a man can be assured that any child the woman conceives shares at least some of his genes: 50 percent if he’s the father and 25 percent if his brother is the father. When one of the brothers acquires enough resources to support a wife on his own, he often does so, leaving the polyandrous family (Schmitt, 2005).

A special form of polyandry occurs in some South American hunter-gatherer groups, who believe that a child possesses some of the characteristics of any man the mother has sex with approximately 10 months before birth, termed partible paternity. Although a woman may have a husband and be in a monogamous relationship, a pregnant woman may initiate affairs with other, often high-status men. As a result, these men may protect or even provide resources to “their” child, resulting in a higher survival rate for children compared to those without “multiple fathers” (Beckerman & Valentine, 2002).

SECTION REVIEW

An evolutionary perspective offers functionalist explanations of mating patterns.

Relation of Mating Patterns to Parental Investment

- Trivers theorized that sex differences in parental investment (time, energy, risk involved in bearing and raising young) explain mating patterns and sex differences in size, aggressiveness, competition for mates, and selectivity in choosing mates.

- Consistent with Trivers’s theory, polygyny is associated with high female and low male parental investment; polyandry is associated with the opposite; monogamy is associated with approximately equal investment by the two sexes; and promiscuity, common to chimps and bonobos, seems to be associated with high investment in the group.

Human Mating Patterns

- Parental investment is somewhat lower for fathers than for mothers, consistent with the human mix of monogamy and polygyny.

- Romantic love and jealousy help promote and preserve bonding of mates, permitting two-parent care of offspring.

- Both sexual faithfulness and unfaithfulness can be evolutionarily adaptive, depending on conditions.

93