9.1 Overview: An Information-Processing Model of the Mind

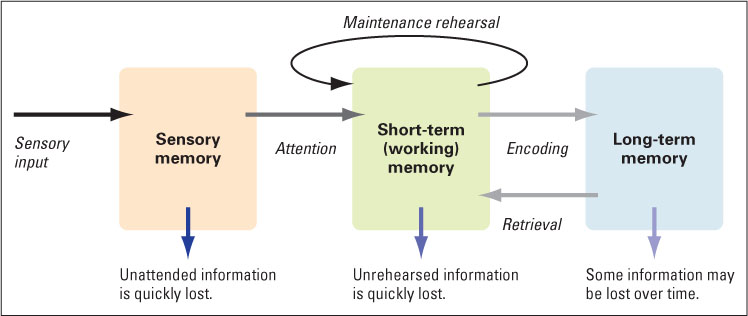

As we noted in Chapter 1, cognitive psychologists commonly look at the mind (or brain) as a processor of information, analogous to a computer. There is no single information-processing theory of cognition. Rather, information-processing theories are built on a set of assumptions concerning how humans acquire, store, and retrieve information. One core assumption of information-processing approaches is that an individual has limited mental resources in processing information. We only have so much mental energy, storage space, or time to devote to the processing of information. A second core assumption is that information moves through a system of stores, as depicted in Figure 9.1. Information is brought into the mind by way of the sensory systems, and then it can be manipulated in various ways, placed into long-term storage, and retrieved when needed to solve a problem.

1

What are the main components of the information-processing model of the mind presented here?

Versions of this information-processing model were first proposed in the 1960s (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968; Waugh & Norman, 1965), and it has served ever since as a general framework for thinking and talking about the mind. As you use this model throughout this chapter, keep in mind that it is only a model. It is simply a way of trying to make sense of the data from many behavioral studies. Like any model, it can place blinders on thought and research if taken literally rather than as a metaphor.

The model portrays the mind as containing three types of memory stores—sensory memory, short-term (or working) memory, and long-term memory—conceived of metaphorically as places (boxes in the diagram) where information is held and operated on. Each store type is characterized by its function (the role it plays in the overall workings of the mind), its capacity (the amount of information it can hold at any given instant), and its duration (the length of time it can hold an item of information). In addition to the stores, the model specifies a set of control processes, including attention, rehearsal, encoding, and retrieval, which govern the processing of information within stores and the movement of information from one store to another. As a prelude to the more detailed later discussions, here is a brief description of the three stores and the control processes.

323

Sensory Memory: The Brief Prolongation of Sensory Experience

When lightning flashes on a dark night, you can still see the flash and the objects it illuminated for a split second beyond its actual duration. Somewhat similarly, when a companion says, “You’re not listening to me,” you can still hear those words, and a few words of the previous sentence, for a brief time after they are spoken. Thus, you can answer (falsely), “I was listening. You said …”—and then you can repeat your annoyed companion’s last few words even though, in truth, you weren’t listening when the words were uttered. These observations demonstrate that some trace of sensory input stays in your information-processing system for a brief period—less than 1 second for sights and up to several seconds for sounds—even when you are not paying attention to the input. This trace and the ability to hold it are called sensory memory

2

What is the function of sensory memory?

A separate sensory-memory store is believed to exist for each sensory system (vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste), but only those for vision and hearing have been studied extensively. Each sensory store is presumed to hold, very briefly, all the sensory input that enters that sensory system, whether or not the person is paying attention to that input. The function of the store, presumably, is to hold on to sensory information, in its original sensory form, long enough for it to be analyzed by unconscious mental processes and for a decision to be made about whether or not to bring that information into the short-term store. Most of the information in our sensory stores does not enter into our consciousness. We become conscious only of those items that are transformed, by the selective process of attention, into working memory.

The Short-Term Store: Conscious Perception and Thought

3

What are the basic functions of the short-term store and how is this memory store equated with consciousness? In what way is the short-term store like the central processing unit of a computer?

Information in the sensory store that is attended to moves into the next compartment, which is called the short-term store (the central compartment in Figure 9.1), a term that calls attention to the relatively fleeting nature of information in this store; each item fades quickly and is lost within seconds when it is no longer actively attended to or thought about. This is conceived of as the major workplace of the mind, and thus sometimes referred to as working memory. More recently, working memory has been used to refer to the process of storing and transforming information being held in the short-term store, and we will examine working memory from this perspective later in this chapter. Short-term store is, among other things, the seat of conscious thought—the place where all conscious perceiving, feeling, comparing, computing, and reasoning take place.

324

As depicted by the arrows in Figure 9.1, information can enter the short-term store from both the sensory-memory store (representing the present environment) and the long-term-memory store (representing knowledge gained from previous experiences). In this sense, the short-term store is analogous to the central processing unit of a computer. Information can be transmitted into the computer’s central processing unit from a keyboard (comparable to input from the mind’s sensory store), or it can be entered from the computer’s hard drive (comparable to input from the mind’s long-term store). The real work of the computer—computation and manipulation of the information—occurs within its central processing unit.

The sensory store and long-term store both contribute to the continuous flow of conscious thought that constitutes the content of the short-term store. Flow is an apt metaphor here. The momentary capacity of the short-term store is very small—about seven plus or minus two items (Miller, 1956); only a few items of information can be perceived or thought about at once. Yet the total amount of information that moves through the short-term store over a period of minutes or hours can be enormous, just as a huge amount of water can flow through a narrow channel over time.

Long-Term Memory: The Mind’s Library of Information

Once an item has passed from sensory memory into the short-term store, it may or may not then be encoded into long-term memory (again, see Figure 9.1 on page 322). Long-term memory corresponds most closely to most people’s everyday notion of memory. It is the stored representation of all that a person knows. As such, its capacity must be enormous. Long-term memory contains the information that enables us to recognize or recall the taste of an almond, the sound of a banjo, the face of a grade-school friend, the names of the foods eaten at supper last night, the words of a favorite song, and the spelling of the word song. We are not conscious of the items of information in our long-term store except when they have been activated and moved into the short-term store. According to the model, the items lie dormant, or relatively so, like books on a library shelf or digital patterns on a computer disk, until they are called into the short-term store and put to use.

As you can see from our brief description, long-term memory and the short-term store are sharply differentiated. Long-term memory is passive (a repository of information), and the short-term store (working memory) is active (a place where information is thought about). Long-term memory is of long duration (some of its items last a lifetime), whereas the short-term store is of short duration (items disappear within seconds when no longer thought about). Long-term memory has essentially unlimited capacity (all your long-lasting knowledge is in it), and the short-term store has limited capacity (only those items of information that you are currently thinking about are in it).

Control Processes: The Mind’s Information Transportation Systems

4

In the information-processing model, what are the functions of attention, encoding, and retrieval?

According to the information-processing model presented in Figure 9.1, the movement of information from one memory store to another is regulated by the control processes of attention, encoding, and retrieval, all indicated in Figure 9.1 by arrows between the boxes. Control processes can be thought of as strategies for moving information through the system and enhancing performance.

Attention, as the term is used here, is the process that controls the flow of information from the sensory store into the short-term store. Because the capacity of sensory memory is large and that of the short-term store is small, attention must restrict the flow of information from the first into the second.

325

Encoding is the process that controls movement from the short-term store into the long-term store. When you deliberately memorize a poem or a list of names, you are consciously encoding it into long-term memory. Most encoding, however, is not deliberate; rather, it occurs incidentally, as a side effect of the special interest that you devote to certain items of information. If you become interested in, and think about, ideas in this book you will, as a side effect, encode many of those ideas and the new terms relating to them into long-term memory.

Retrieval is the process that controls the flow of information from the long-term store into the short-term store. Retrieval is what we commonly call remembering or recalling. Like attention and encoding, retrieval can be either deliberate or automatic. Sometimes we actively search our long-term store for a particular piece of information. More often, however, information seems to flow automatically into the working store from the long-term store. One image or thought in working memory seems to call forth the next in a stream that is sometimes logical, sometimes fanciful.

As we mentioned previously, the short-term store has a limited capacity. We can only encode, retrieve, or attend to so much information at any one time. Any control process can be viewed as requiring a certain proportion of the system’s limited capacity for its execution. One way of thinking about this is to ask how much mental energy any particular process takes. Although we can’t compute brain energy consumption like we can compute the number of miles per gallon our car uses, researchers can measure via neuroimaging techniques how much glucose is consumed executing a mental operation. Glucose is a source of energy for the brain, and the more that is used the more energy is required for an operation’s execution. Research has shown that glucose consumption in brain areas associated with cognitive processing is greater (that is, more resource consuming) when executing more difficult tasks relative to those that are easier (that is, less resource consuming) (Haier et al., 1992). This provides convincing evidence that the “energy” metaphor for the information-processing system’s limited capacity is an apt one.

Individual mental operations can also be placed on a continuum with respect to how much of one’s limited capacity each requires for its execution (Hasher & Zacks, 1979). At one extreme are effortful processes, which require the use of mental resources for their successful completion; at the other extreme are automatic processes, which require little or none of the short-term store’s limited capacity. In addition to not requiring any mental effort, truly automatic processes are hypothesized: (1) to occur without intention and without conscious awareness; (2) not to interfere with the execution of other processes; (3) not to improve with practice; and (4) not to be influenced by individual differences in intelligence, motivation, and education (Hasher & Zacks, 1979). In contrast, effortful processes are hypothesized to: (1) be available to consciousness; (2) interfere with the execution of other effortful processes; (3) improve with practice; and (4) be influenced by individual differences in intelligence, motivation, and education.

Processes closer to the automatic end of the continuum, such as keeping track of the approximate frequency of certain events or understanding sentences that are spoken to you, may develop without any explicit practice. Others, such as reading or driving a car, can develop with practice. These operations are at first very effortful and require your full attention, but with practice are done “effortlessly.” Of course, some mental effort is expended even on these well-learned tasks, as reading rate or driving performance will decline when there are distractions or the reader/driver engages in a secondary task (for example, texting while driving). Everyday cognition involves a constant combination of automatic (and unconscious) and effortful (and conscious) processes, some of which we will examine in this and the following chapter.

326

SECTION REVIEW

The standard information-processing model posits three memory stores and various control processes.

Sensory Memory

- A separate sensory store for each sensory system (vision, hearing, etc.) holds brief traces of all information registered by that system.

- Unconscious processes may operate on these traces to determine which information to pass on to working memory.

The Short-Term Store

- This store is where conscious mental work takes place on information brought in from sensory memory and long-term memory, and thus it is sometimes called working memory.

- It is called short-term memory because information in it that is no longer attended to quickly disappears.

Long-Term Memory

- This is the repository of all that a person knows.

- Information here is dormant, being actively processed only when it is brought into the short-term store.

Control Processes

- Attention brings information from sensory memory into the short-term store.

- Encoding brings information from the short-term store into long-term memory.

- Retrieval brings information from long-term memory into the short-term store.

- Cognitive processes can be placed on a continuum from effortful to automatic.