12.3 Situational Triggers of Aggression: The Context Made Me Do It

We have seen how our evolutionary inheritance and biological systems give each of us a capacity for hostile feelings and aggression, a capacity that we are most likely to engage when something or someone thwarts our needs and desires. It makes sense, then, that the study of situational factors that provoke affective aggression begins by focusing on frustration. Imagine a brutal school day. You start your morning missing seemingly every traffic light as you race to campus, already late for an exam. Finally you get to class. The day that follows is filled with similar frustrations. On getting home, you open the door and trip over the dog, prompting a profanity-

The Frustration-Aggression Hypothesis

In 1939 a group of psychologists at Yale University first proposed the frustration-

Frustration-aggression hypothesis

Originally the idea that aggression is always preceded by frustration and that frustration inevitably leads to aggression. Revised to suggest that frustration produces an emotional readiness to aggress.

During the first half of the 20th century Hovland and Sears (1940) reported that the number of lynchings of African Americans by Whites in the American South correlated negatively with the value of cotton, which at the time dominated the southern economy. The researchers presumed that as the price of cotton went down, southern Whites became more frustrated at their economic misfortunes. This frustration led to more aggression against African Americans. More contemporary findings show that, across diverse cultures, aggressive behaviors (e.g., homicide, road rage, child abuse) increase with the prevalence of various sources of frustration and stressors, including shrinking workforce, unemployment, increase in population density, low economic status, and economic hardship (Geen, 1998).

Displaced Aggression

In many cases, frustration-

Displaced aggression

Aggression directed to a target other than the source of one’s frustration.

436

Triggered displaced aggression occurs when someone does not respond to an initial frustration or provocation (i.e., the bad day at school) but later is faced with a second event that elicits a more aggressive response than would be warranted by only the relatively minor affront on its own (the dog stepping on your foot). Miller and colleagues (2003) suggest that the original provocation produces anger and aggressive thoughts. However, because the individual is prevented from retaliating, or decides not to retaliate, against the original provocation, the hostile feelings and thoughts remain. Then, when the individual is confronted with a second, actually minor, frustrating event, the preexisting hostility biases how he or she interprets and emotionally responds to that event. In the context of the bad day, your dog being in position to trip you seems more intentional and more painful, leading you to behave more aggressively than is warranted. The more the provoked person ruminates about the initial aversive event, the more likely triggered displaced aggression will occur (Bushman, Bonacci et al., 2005).

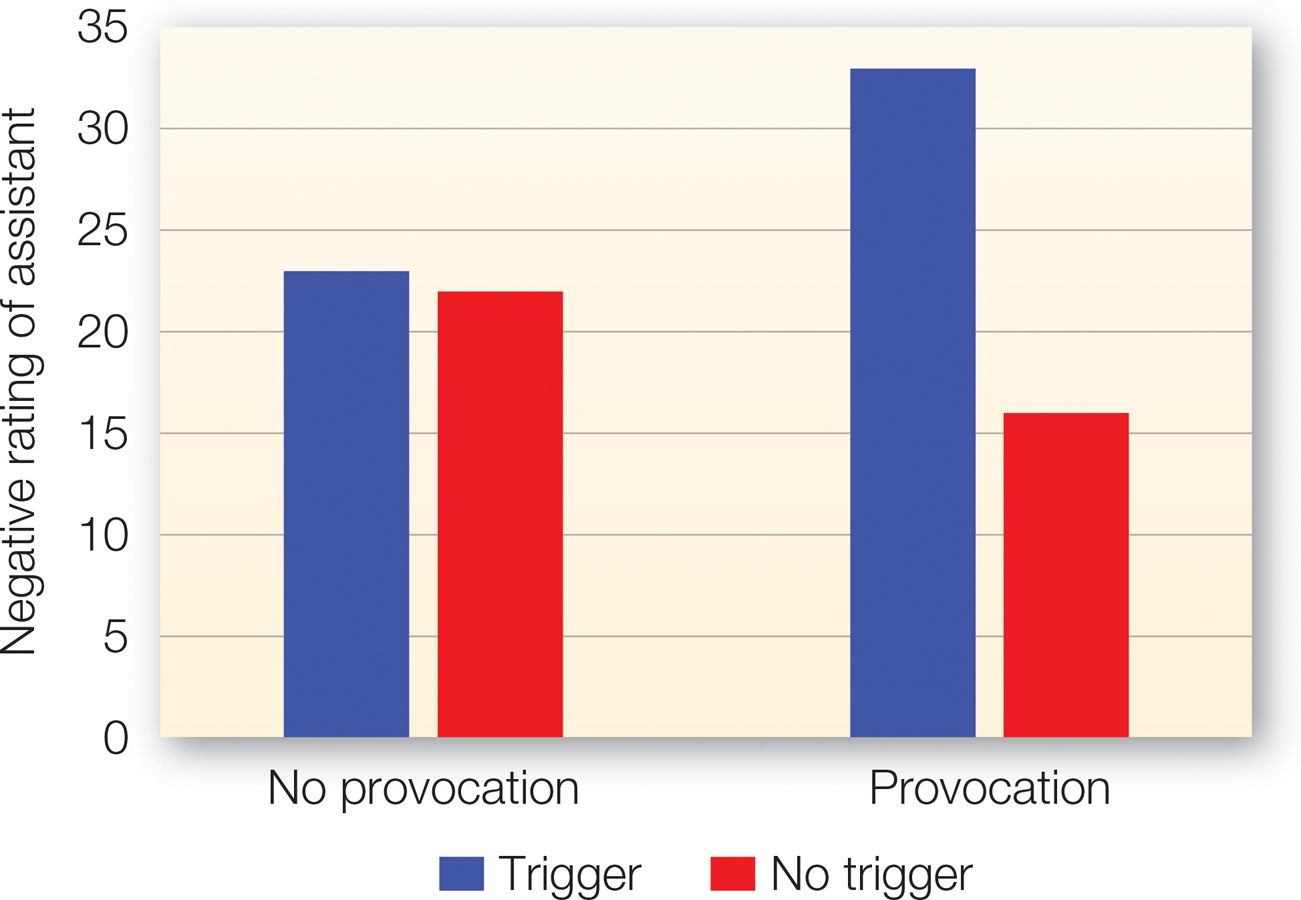

FIGURE 12.4

Triggered Displaced Aggression

When rating a somewhat bumbling assistant (in the trigger condition), participants made the harshest evaluations if they had been insulted earlier by someone else. This situation illustrates triggered displaced aggression because participants derogated the assistant only if he or she did something to trigger the aggressive response.

[Data source: Pedersen et al. (2000)]

A study by Pedersen and colleagues (2000) provides a good illustration of how this works. Participants were initially given either insulting feedback about their performance on a task or no such feedback. The initial, insulting feedback is a provocation. Later in the study, the participants were given another task by a different assistant. In one condition, the assistant was somewhat annoying and incompetent, whereas the other participants had no such minor trigger. Participants were then given the opportunity to rate the assistant’s qualifications for a job. As can be seen in FIGURE 12.4, in the absence of an initial provocation, participants were not especially critical of the bumbling assistant. However, when participants had initially been insulted and were then exposed to the annoying assistant, they subsequently gave her a much more negative evaluation.

What this and other studies reveal is that we don’t displace our aggression against just anyone. Rather, we are most likely to lash out at targets who do something mildly annoying, are dislikable, are relatively low in social status and power, or who resemble the person with whom we actually are angry (e.g., Marcus-

Arbitrariness of the Frustration

Think ABOUT

Although the studies we’ve reviewed so far support a role for frustration in aggression, other studies showed that the original hypothesis was too absolute. Although frustrated people sometimes aggress, they often do not. Can you think of times when frustration led you to aggress? What about times when you were frustrated but did not aggress? The questions for social psychologists become: When do frustrating circumstances lead to aggression? When do they not?

One factor that researchers discovered very quickly was whether the frustration seemed to be justified or arbitrary. Imagine stepping up to the refreshment counter at a movie theater and being denied a large container of buttered popcorn. If the snack-

437

Attacks, Insults, and Social Rejection

Perhaps the most reliable provocation of an aggressive response is the belief that one has or will be attacked intentionally, either physically or verbally (Geen, 2001). What could be more frustrating than being attacked or insulted? For example, in one study (Harmon-

Although it is not surprising that physical attack often leads to counterattack, if only for self-

Experimental research provides further support for the role of rejection. For example, in one study (Twenge et al., 2001), all participants had a 15-

Of course, people don’t always respond to rejection by becoming more aggressive. Sometimes, they become withdrawn and despondent. At other times, they seek acceptance (e.g., Leary et al., 2006). As with all conditions that arouse hostile feelings, other variables we will consider throughout this chapter help determine whether aggression or other responses to those feelings are more likely. But one factor particularly predictive of aggression in response to rejection is a personality trait called rejection sensitivity. People high in rejection sensitivity tend to expect, readily perceive, and overreact to rejection with aggressive responses (Ayduk et al., 2008).

438

When Do Hostile Feelings Lead to Aggression? The Cognitive Neoassociationism Model

After years of research, Berkowitz (1989) provided a particularly valuable additional answer to the “when” question in the form of his cognitive neoassociationism model. This model expands on the frustration-

Physical Pain and Discomfort

It turns out that when people are hurt physically as well as emotionally, they are more likely to lash out: Physical pain triggers aggression. In one study that made this point, Berkowitz and colleagues (1981) had participants immerse one hand either in a bucket of freezing-

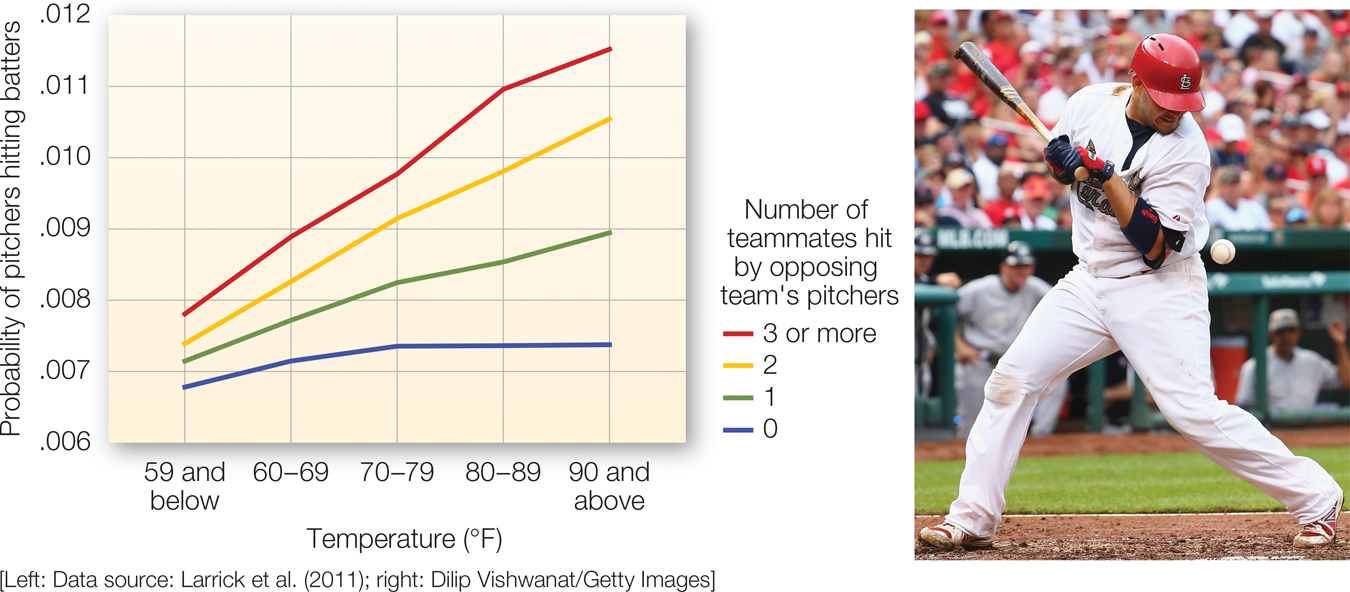

FIGURE 12.5

It’s Getting Hot in Here

When temperatures are especially hot, tempers also rise. Major League Baseball pitchers were more likely to hit batters the hotter the temperature, especially if their teammates were hit earlier in the game.

Excessive heat can also cause discomfort, and several studies show that heat-

The Role of Arousal in Aggression

As shown by Schachter’s two factor theory of emotions (see chapter 5), under some conditions, the more arousal individuals experience, the stronger their emotional reactions will be. So when anger seems to be the appropriate response to a situation, extra sources of arousal may intensify the anger and subsequent aggression. According to Zillmann’s (1971) excitation transfer theory (chapter 5), when people are still physiologically aroused by an initial event, but are no longer thinking about what made them aroused, this residual (or unexplained) excitation can be transferred and interpreted in the context of some new event. As a result, people who are already aroused are likely to overreact to subsequent provocations with intensified anger and aggression.

439

Consider the following demonstration (Zillmann & Bryant, 1974). Participants were told they would be playing a game with an opponent who was actually a confederate. Some participants were asked to ride an exercise bike, while others performed a less vigorous activity. Two minutes later a confederate either insulted them or treated them in a neutral manner. Then, about 6 minutes after the first activity when participants were still aroused by the exercise but no longer aware of it, they were given the opportunity to deliver a punishing noxious noise to the person who had previously angered them. Do you think you might be more or less aggressive after exercising? Though the idea of catharsis or “blowing off steam” might lead you to think the exercise would provide a release, purging you of aggressive inclinations, the results were quite the opposite. In accord with excitation transfer theory, those participants who engaged in exercise and were insulted actually delivered more of the noxious noise than the other participants. The excitation of exercise intensified their anger at the insulter, and thus intensified their aggressive behavior. A follow-

Priming Aggressive Cognitions

Taking the social cognitive perspective, Berkowitz’s cognitive neoassociationist model also proposes that hostile feelings will be especially likely to lead to aggression when hostile cognitions are primed by cues in the person’s situation. What are some of the most common environmental cues that prime violence and aggression? One big category that stands out is firearms. This leads us to a discussion of one of the seminal studies of aggression—

Weapons effect

The tendency for the presence of firearms to increase the likelihood of aggression, especially when people are frustrated.

440

Imagine that you show up to take part in a study as participants did in Berkowitz and LePage (1967). You are told the study is exploring the connection between physiology and stress. You’re informed that another participant (actually a confederate) will be grading ideas that you come up with for a task by administering electric shocks to you (1 shock = good answers, 7 shocks = bad answers). After generating your ideas, you get hit with 7 shocks (an outcome likely to anger most people). Other participants in the study are randomly assigned to receive just the minimal 1 shock, and likely feel less angry as a result. After this, you’re brought to the room with the shock generator and given the chance to retaliate by administering electric shocks to the person who just shocked you. The second manipulation is whether people administered these shocks with a neutral object (e.g., a badminton racquet) sitting on the desk next to the shock generator, with nothing else on the desk, or—

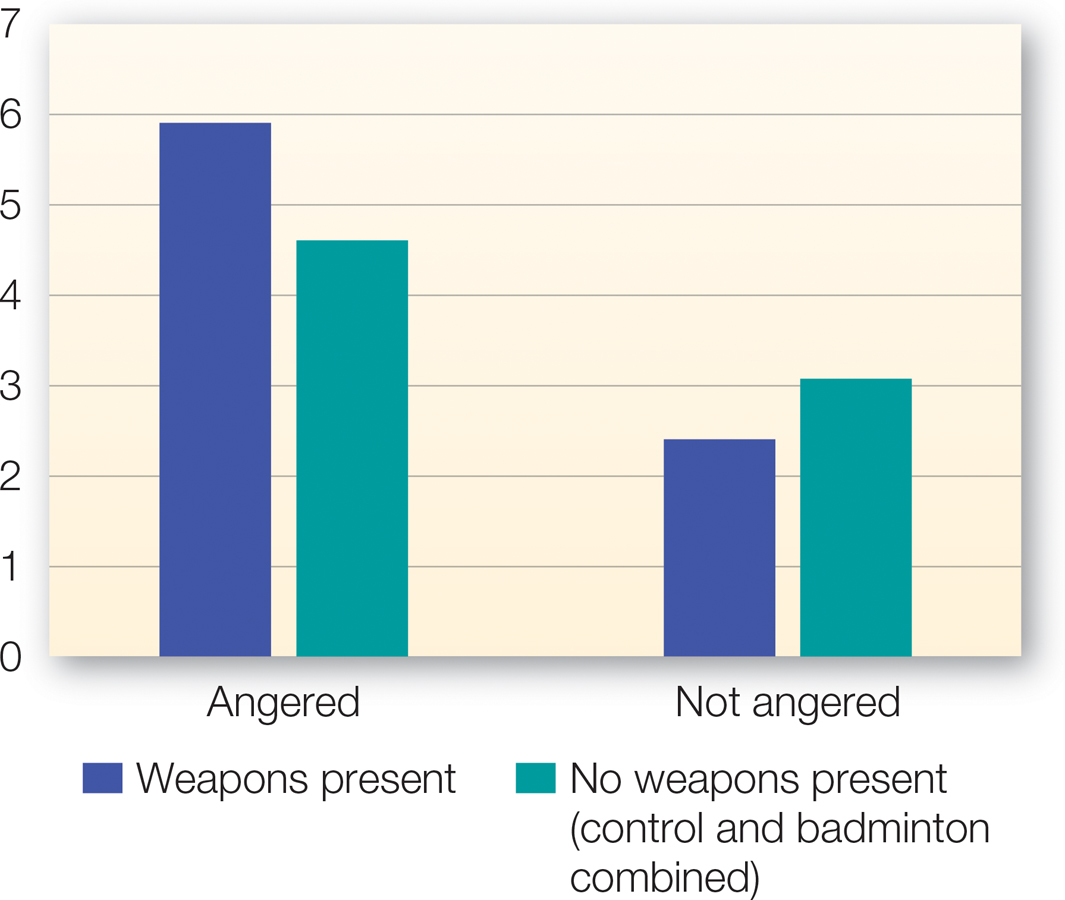

FIGURE 12.6

The Weapons Effect

Berkowitz and LePage’s (1967) classic weapons-

[Data source: Berkowitz & LePage (1967)]

Check out FIGURE 12.6. If participants were not previously made angry, the presence of weapons had no effect on their level of aggression. Similarly, if participants were angry but not in the presence of weapons, they were more aggressive, but not overly so. Yet a very different effect emerged when participants were both made angry and in the presence of weapons. In this condition, they administered the greatest number of intense electric shocks.

You might be wondering whether something like this could happen outside the laboratory. You bet it could. In one field study, researchers got a pickup truck with a gun rack and had it stall at a traffic light (Turner et al., 1975). In one condition, there were two cues associated with violence: a military rifle in the gun rack and a bumper sticker that read “VENGEANCE.” In another condition, there was one cue—

Why does the weapons effect occur? One reason is that weapons prime aggression-

Stimuli other than firearms also can become associated with violence and therefore can prime cognitions that encourage aggression. In one study, a violent film scene involving the actor Kirk Douglas led to more aggression against a provoking confederate if he was named Kirk instead of Bob (Berkowitz & Geen, 1967). In another study, Josephson (1987) showed seven-

441

So stimuli other than guns can become cues that encourage aggression, but will guns always do so? It largely depends on the associations that a person has with the object. Although for many people guns have an associative history with violence and aggression, this is not the case for everyone. People who hunt for sport may see guns in a different light. As a result they don’t tend to show activation of aggressive cognitions and are not more aggressive toward those who provoke them when exposed to pictures of guns; in contrast, nonhunters are (Bartholow et al., 2005). For hunters, pictures of guns actually arouse warm and pleasant cognitions (perhaps reflecting the enjoyable times with family and friends while they’ve hunted). But when hunters are shown pictures of assault rifles, which have no connection to recreational sport, they do show increased aggressive cognitions and behavior. Thus, the weapons effect critically depends on the person’s prior learning and experiences.

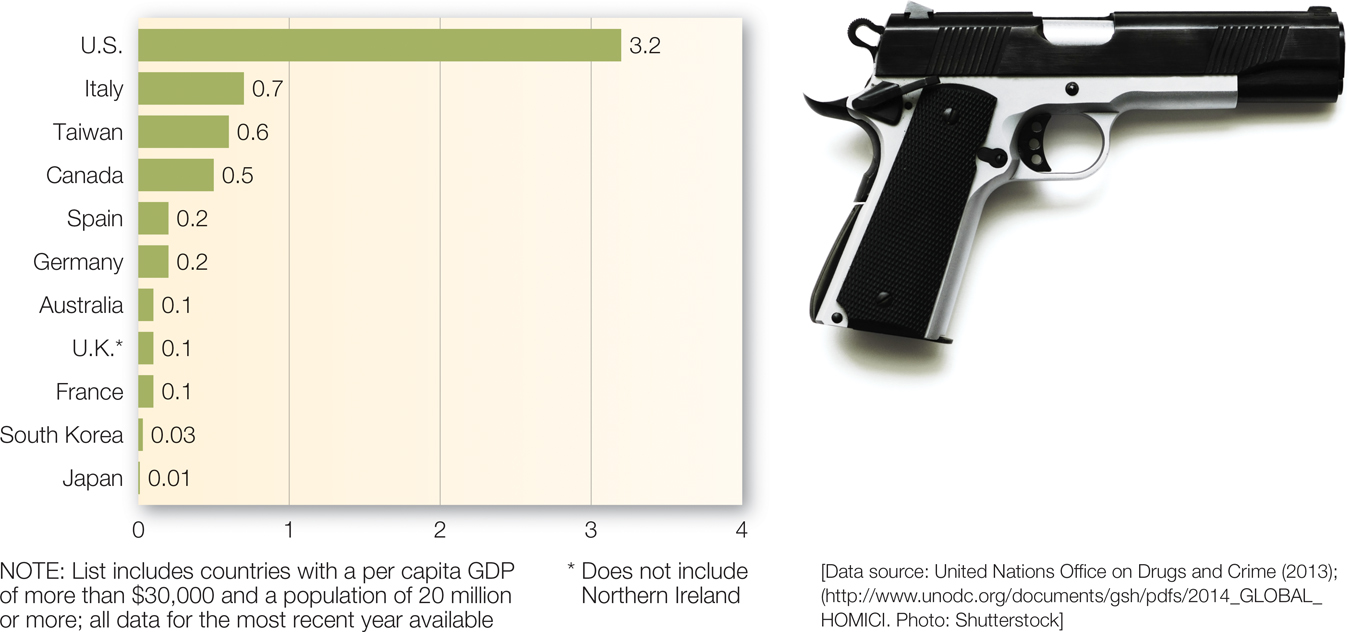

FIGURE 12.7

Gun-

Gun-

Of course, most Americans are not recreational hunters. Thus these weapons-

442

Inhibitors of Aggression

We’ve covered a lot of evidence on facilitators of hostile feelings and thoughts that lead to aggression, but can you think of times you were angry and thought about acting aggressively, but did not? What factors inhibit people from acting on their hostile feelings and thoughts? Moral values that forbid hurting others, feelings of empathy for others, and consideration of possible aversive consequences for oneself, such as prison or retaliation, all play a role in whether people choose aggression or other responses, particularly when the capacity for self-

|

Situational Factors in Aggression: The Context Made Me Do It |

|

Unpleasant, frustrating experiences arouse hostile affect, which makes us prone to aggression, particularly when situational cues prime aggressive cognitions. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Frustration- Frustration produces an emotional readiness to aggress. Conditions of the situation can then trigger an aggressive response. Displaced aggression is aggression directed at targets other than those that caused the frustration. Triggered displaced aggression is targeted against a secondary, even minor, source of frustration. |

Factors that increase aggressive responses Aggression is more likely: if the frustration is arbitrary. if there is an expectation of physical or verbal attack, insult, or social rejection. in response to physical pain, heat, and discomfort. if the individual has residual arousal from prior events. |

Facilitators and inhibitors of aggression Stimuli that arouse hostile feelings are most likely to lead to aggression if there is a situational cue, such as a nearby weapon, that primes aggressive cognitions. Morals, empathy, and consideration of consequences can mitigate the effects of hostile feelings and cognitions. |