12.4 Learning to Aggress

Sometimes the punishment for and media attention on violent actions can make them rewarding, as was the case with the bank robber John Dillinger, who was glamorized by newspapers in his day, and in the film Public Enemies, in which Johnny Depp played him.

One of the great adaptive features of our species is our capacity for learning, our ability to develop new responses to particular situations on the basis of our experiences in the world. But this capacity also means that much of our propensity for aggression is something that we learn. Some learning of aggression is based on operant conditioning. Beginning in early childhood, we all engage in some aggressive acts such as biting, hitting, shoving, kicking, verbal aggression, and so forth. The more these aggressive actions are reinforced in particular situations, the more frequently an individual will turn to additional aggression in similar contexts (e.g., Geen & Pigg, 1970; Geen & Stonner, 1971; Loew, 1967). In other words, if these actions garner desired attention or specific rewards, or if they alleviate negative feelings, they will become more likely (Dengerink & Covey, 1983; Geen, 2001). If Taylor hits Tim to get his lollipop, Taylor’s aggression will be reinforced if the consequence is successfully enjoying a tasty lollipop. If a child is hassled and made fun of by other kids, but finds that aggressive action alleviates the hassling, the child is likely to learn that physical aggression is a way to get relief from being bothered by others. And in gang subcultures, members may win admiration for engaging in violence (Wolfgang & Ferracuti, 1967).

443

On the other hand, if aggressive actions do not lead to rewarding experiences, or if they lead to unpleasant experiences, the likelihood of aggression should be reduced. However, punishment does not inhibit actions nearly so well as rewards encourage them. And in some cases, attempts at punishment may actually be reinforcing because they inadvertently bring desired attention to the child. This can occur with adults as well. Throughout history, outlaws such as the bank robber John Dillinger, depicted in the movie Public Enemies, gained attention, publicity, and even fame for their violent actions (Brown et al., 2009).

FIGURE 12.8

Does Killing Beget Killing?

When participants believed they were grinding up bugs in this modified coffee grinder, those who initially killed five bugs justified their aggression by killing even more later.

There is another reason one’s own aggressive actions tend to encourage more aggressive actions. When people act aggressively, they can feel dissonance or guilt, which leads them to shift their attitudes to justify their actions. Martens and colleagues (2007) showed that the more pill bugs participants were instructed to kill by dropping them into what they thought was a bug-

In addition to learning to aggress through their own actions, people also learn to aggress by watching the actions of others. Humans have a great capacity for imitation and observational learning (Bandura, 1973). Indeed, most children probably learn more about aggression from electronic media sources, from watching their parents and peers, and from their cultural upbringing than they do from their own actions. So let’s take a careful look at how the electronic media, family life, and culture contribute to aggression.

Electronic Media and Aggression

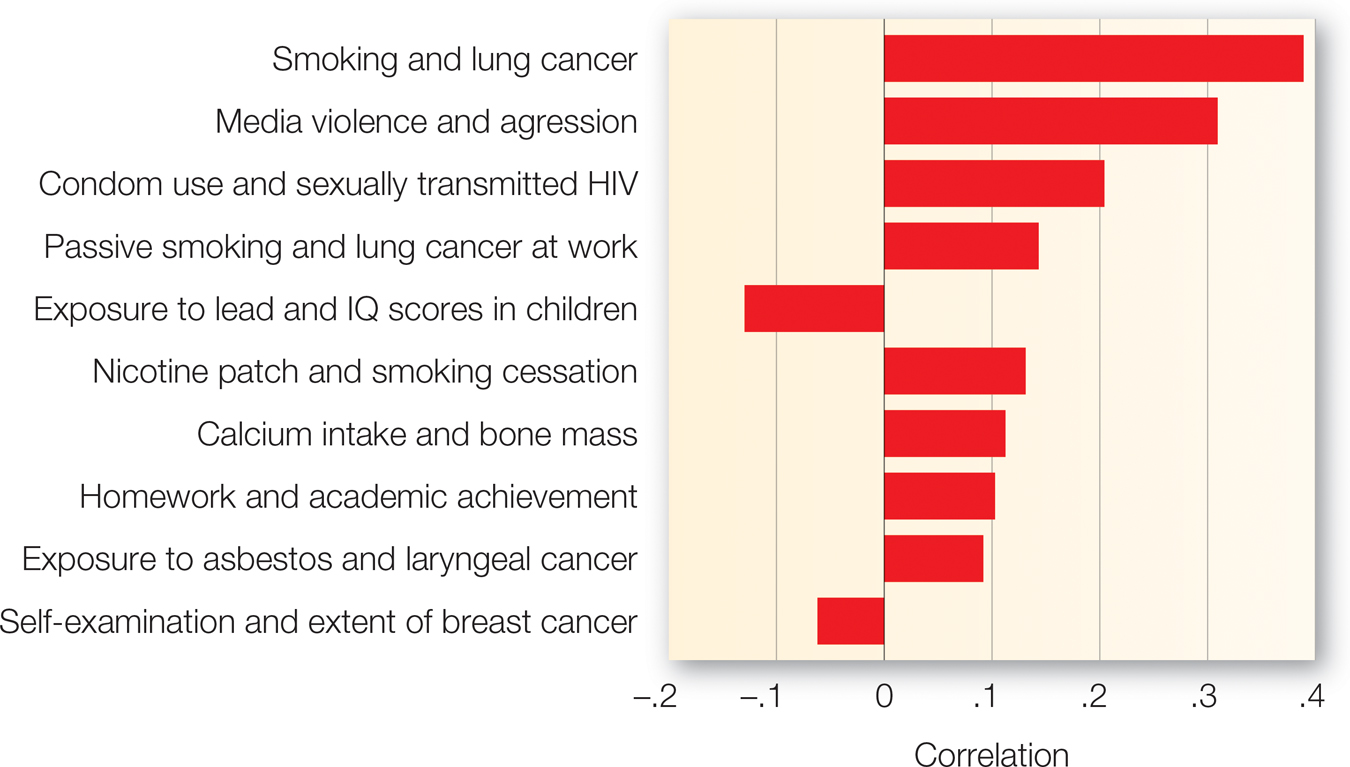

FIGURE 12.9

Does Media Violence Matter?

The effect of violence in the media on actual aggression seems to be just as strong as, and in many cases stronger than, a number of influences that go unquestioned in society.

[Data source: Bushman & Anderson (2001)]

A large body of research shows that exposure to violent media increases the prevalence of aggression in a society (e.g., Bushman & Huesmann, 2010). In fact, the relationship between exposure to media depictions of violence and aggressive behavior is stronger than many other relationships that are considered very well established, including, for example, the extent to which condom use predicts likelihood of contracting HIV and the extent to which calcium intake is related to bone mass (see FIGURE 12.9) (Bushman & Anderson, 2001). Despite this evidence, violent content is pervasive in modern television programming, films, and video games and on the Internet (Donnerstein, 2011).

Bushman and Anderson argued that one reason these research findings are largely ignored is that violent media are very popular and therefore profitable. Consequently, news media outlets, which often are connected to the businesses that gather these profits, tend to be biased in their reporting of the evidence. To illustrate the profitability of film violence, as this textbook goes to press, all of the top 10 highest-

444

What Is the Appeal of Media Violence?

Violence and smut are of course everywhere on the airwaves. You cannot turn on your television without seeing them, although sometimes you have to hunt around.

—Dave Barry (1966)

Why is violent entertainment so popular? From the evolutionary perspective, it’s likely been adaptive for humans to be innately vigilant to viewing, and physiologically aroused by, instances of violence (e.g., Beer, 1984). As the old journalism cliché goes, “If it bleeds, it leads.” If there is potential danger, we want to know what, where, how, and why. And well we should, so that we can prepare for fight or flight. The entertainment industry takes advantage of these innate tendencies. Although people don’t like it directed at themselves, they do enjoy seeing violence in movies on TV or enacting it in video games—

The other easy way to make viewers excited is with sexually appealing images, another feature of much popular entertainment, as Dave Barry noted. But in American culture, younger viewers are shielded much more strictly from sexual content than they are from violent content. For example, in movie ratings a single exposed penis or breast guarantees an R rating, whereas massive amounts of killing can now be found in many PG-

445

Another basis of the appeal of violent media is the portrayal of heroic victories over evil and injustice (e.g., Goldstein, 1998; Zillmann, 1998). One of the first violent American TV shows, The Adventures of Superman, expressed this very succinctly: Superman fights for “truth, justice and the American way.” For American children watching that show, what could be better than that? Identifying with such heroes may provide a boost in self-

The Basic Evidence for Violent Media’s Contributing to Aggression

You may be thinking to yourself, “Well, I watch a lot of violent entertainment and play video games, and I don’t go around hurting other people.” As we noted earlier, aggression is not caused by any one factor in isolation but results from particular combinations of coexistent causal factors. Let’s examine the evidence that exposure to media violence is one of those causal factors.

As first-

Research has shown clearly that the more violence an individual watches, the more aggressive that person is (e.g., Singer & Singer, 1981). Of course, this finding is merely a correlation and so could mean either that violent entertainment causally contributes to aggression or that viewers who like aggression are more likely to watch violent entertainment. Longitudinal evidence (i.e., studies that follow people over time) suggests that the former causal pathway provides the more likely explanation (e.g., Huesmann et al., 1984, 2003; Lefkowitz et al., 1977). The more violent programs an individual watches as a child, the more likely that individual is to be violent up to 22 years later as an adult. In contrast, level of aggressiveness as a child does not similarly predict interest in watching violent programs as an adult. Similar findings are emerging for violent video-

The best way to assess a causal effect of exposure to violence on aggression is to conduct field studies and experiments in which some participants are randomly assigned to watch violent or nonviolent content (e.g., Berkowitz, 1965; Geen & Berkowitz, 1966). The findings of many such studies show that exposure to media violence through watching videos or playing video games increases aggression (Bushman & Huesmann, 2010; Geen, 2001). Let’s consider two examples that illustrate these effects.

In a home for juvenile delinquent boys, Leyens and colleagues (1975) had boys in two of the cottages watch five nights of violent movies. Boys in two other cottages watched five nights of nonviolent movies. The boys were observed each night for frequency of hitting, slapping, choking, and kicking their cottage mates. The boys who watched the violent films engaged in more such aggressive behavior than those who watched the nonviolent films. In another study, Konijn and colleagues (2007) randomly assigned Dutch adolescent boys to play a violent or nonviolent video game for 20 minutes and then play a competitive game with another study participant. The winner got the privilege of blasting the loser with noise at a volume of their choosing, ranging from a tolerable 60 decibels to a potentially hearing-

446

It’s important to note that the majority of these laboratory experiments show these effects of violent media primarily when participants are frustrated or provoked (e.g., Geen & Stonner, 1973), and for viewers who are generally above average in aggressive tendencies (e.g., Anderson & Dill, 2000; Bushman, 1995). So your likely self-

How and Why Does Watching Violence Contribute to Aggression in Viewers?

The next questions concern how and why violent media have these effects. Social learning theory and research provide some important answers (Bandura, 1973). People tend to imitate the behaviors they observe in others and learn new behaviors from them. As the Bobo doll studies showed (chapter 7), frustrated children who observed an adult model attacking a Bobo doll became more aggressive toward the doll, often in the same specific way that they saw the adult aggress. They also aggressed more if they identified with the adult model and if they observed the model being rewarded for his or her aggression.

Many subsequent experiments, with both children and adults, further support the role of social learning in the effects of observed violence in general, and violence portrayed in films and video material in particular. The more study participants identify with the character they see engaging in filmed violence, the more they are likely to aggress (e.g., Perry & Perry, 1976; Turner & Berkowitz, 1972). In addition, filmed violence is more likely to be imitated if the violence is rewarded rather than punished, if it seems justified rather than unjustified, and if the harm caused by the aggression is deemphasized or sanitized (e.g., Donnerstein, 2011; Geen & Stonner, 1972, 1973). The common television and film scenario in which the hero uses weapons to defeat the villains fits these conditions perfectly: The likable protagonist, easy to identify with, engages in aggression that is justified and leads to a rewarding outcome. Bushman and Huesmann (2010) suggest that these conditions are even more common in violent video games in which the gamer’s character is him-

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

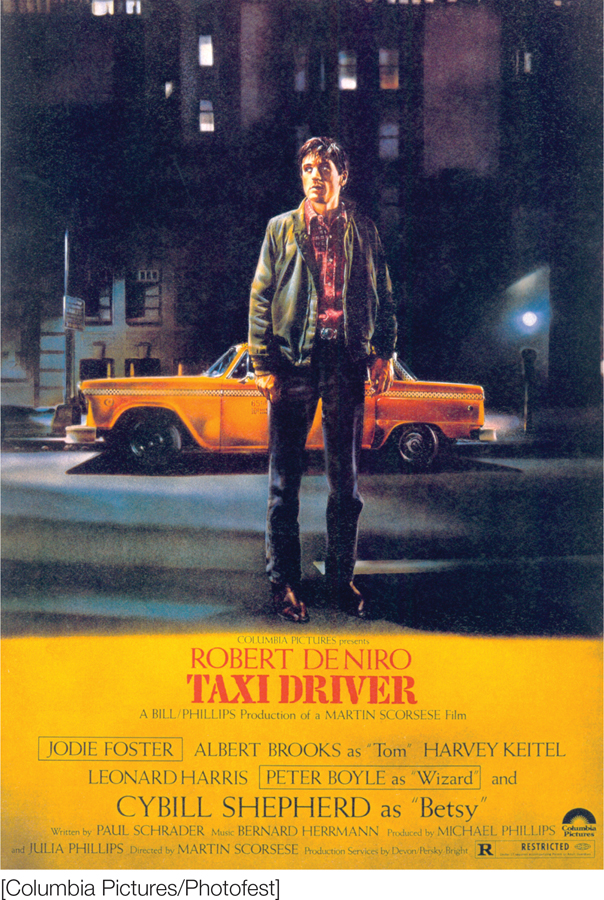

Violence on Film: Taxi Driver

Violence on Film: Taxi Driver

The 1976 classic Martin Scorsese film Taxi Driver (Phillips et al., 1976), starring Robert De Niro as the cabbie Travis Bickle and Jodie Foster as the underage prostitute Iris, was one of the most violent films of its time. It depicts much of what we know about the causes of aggression and the kind of explosive gun violence that has become much more common since the release of the film. Paul Schrader based his screenplay in part on the diary of Arthur Bremer, who had grievously wounded a presidential candidate in an assassination attempt in 1968.

As a former marine who served in Vietnam, Travis has had training in violence (social learning). He is stressed by insomnia, stomach pains, and a sense of alienation and loneliness. He drinks heavily (and therefore might be more disinhibited) and takes amphetamines (which might elevate his arousal). He drives the streets of New York in his cab, witnessing aggression and violent conflict on a nightly basis (violent cues and scripts). He is looking for some way to feel heroic, like a person of significance in the world (low self-

A few years after the film came out, a socially inhibited and lonely young man named John Hinckley, Jr., became obsessed with the film, watching it fifteen times and photographing himself in Travis Bickle poses. He eventually decided that he needed to save Jodie Foster, at the time an undergraduate at Yale University. He made contact with her and sent her flowers. Foster soon recognized Hinckley as an unstable stalker and cut off communication with him. He decided he needed to impress her and wrote her a letter explaining as much. His misguided effort resulted in his attempt to assassinate President Ronald Reagan in 1981. He got close enough to Reagan to wound him seriously with a pistol. He also wounded Reagan’s press secretary James Brady, who was paralyzed by the shooting.

Hinckley’s act of violence, inspired in part by Taxi Driver, caused great physical harm to major government officials but also eventually led to the Brady bill, which requires a three-

The other major long-

447

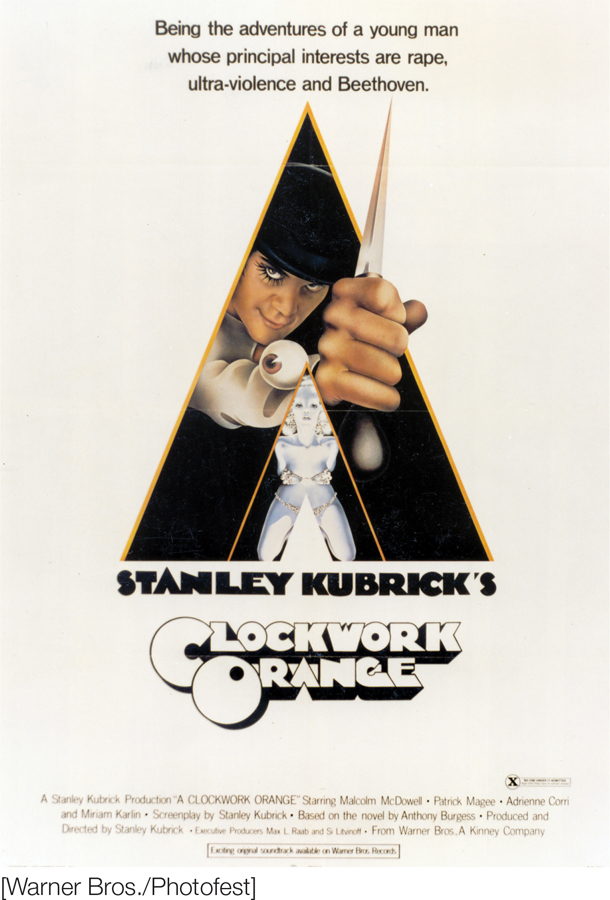

Further evidence of the effects of media violence is provided by instances in which very specific forms of violence depicted in films have been imitated in the real world. In just one of many examples, in 1971, Stanley Kubrick’s disturbing, ultraviolent, dystopian science-

Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film A Clockwork Orange is one of many examples in which media violence seems to have inspired real-

The sociologist David Phillips (1979, 1982) demonstrated a similar imitative tendency by examining frequencies of suicides and car accidents in communities following exposure to news coverage of real-

448

Another noteworthy effect of violent media is that the more violent television people watch, the more they believe that violence is common in the real world (Gerbner et al., 1980, 1982). This sense that the world is unsafe also may contribute to aggressive propensities by increasing a sense of threat and encouraging the idea that aggression is normative. Furthermore, the more children and adults watch media violence, the less they become disturbed by it and the more they become tolerant of it (Drabman & Thomas, 1974; Linz et al., 1989; Thomas et al., 1977). One recent study from the social neuroscience perspective showed that playing a violent video game leads to a reduced physiological reaction in the brain called the P3 response, which indicates a lack of surprise in response to viewing aggression. Furthermore, this neural desensitization helps explain why violent video games tend to increase aggression (Engelhardt et al., 2011). The lower participants’ P3 response to violent stimuli, the more aggressive they were when administering noise blasts to an opponent.

Of course, none of these findings implies that exposure to media violence always increases aggressive tendencies, but it causes such tendencies to be more likely in the short term by making hostile feelings, violent thoughts, and scripts temporarily more accessible (Anderson & Dill, 2000; Berkowitz, 1993; Bushman, 1998; Bushman & Geen, 1990; Bushman & Huesmann, 2006). As the line of work starting with Berkowitz and LePage (1967) showed, when people experience hostile feelings along with violent thoughts, they are more likely to choose aggressive as opposed to nonaggressive ways to deal with those feelings.

In sum, both theory and research suggest the following disturbing conclusion. If 10 million people watch a violent television show or movie, play a violent video game, or listen to violent music lyrics, the majority surely won’t be moved to engage in aggression. However, just as surely, a minority of them—

APPLICATION: Family Life and Aggression

|

APPLICATION: |

| Family Life and Aggression |

Mass-

How does domestic aggression affect children growing up in such circumstances? Just as people who are exposed to a great deal of media violence are more likely to aggress, so are children who are exposed to a great deal of physical aggression and conflict at home (Geen, 1998; Geen, 2001; Huesmann et al., 1984; Straus et al., 1980). A violent family atmosphere generates negative affect and disrupts the psychological security that a consistently loving upbringing would provide. Sibling rivalry, conflicts between parents, lack of affection, and inconsistent discipline by parents all can increase frustration and stress in both toddlers and older children (e.g., Cummings et al., 1981, 1985).

A stressful family life also reinforces and models aggression. Aggressive parents often give children approval for responding aggressively to perceived slights and provocations. Parents who employ corporal punishment to discipline their children also are implicitly teaching that physical aggression is an appropriate way to respond to those perceived as wrongdoers and portrays violence as normative to the child. These lessons communicate that the world is a dangerous place in which most people have negative intentions, which encourages children to see hostile intent in others’ actions (e.g., Dodge et al., 1990).

449

Stress and frustration, disrupted attachment and trust in other people, and training in and modeling of aggression in violent families have both short-

In the long term, children who are exposed to a violent family life are more prone to become aggressive adults (Eron et al., 1991; Hill & Nathan, 2008; McCord, 1983; Olweus, 1995; Straus, 2000). Longitudinal studies find that children subjected to witnessing domestic violence or victimized by abuse are more likely as adults to become spousal abusers and child abusers themselves, creating a vicious cycle perpetuated across generations (Azar & Rohrbeck, 1986; Hotaling & Sugarman, 1990; MacEwen & Barling, 1988; Peterson & Brown, 1994; Widom, 1989). Even though only 2 to 4% of the general population of parents is physically abusive, approximately 30% of abused children grow up to be abusive parents (Gelles, 2007; Kaufman & Zigler, 1987).

Culture and Aggression

As we’ve considered the cultural perspective throughout this book, we’ve seen how culture shapes our values, beliefs, and behavior. Aggression is no exception. As we grow up, we are socialized with particular expectations and into particular roles. Along the way, we also learn how, when, and to what extent aggressive behavior is an acceptable or normative response to certain situations. Some cultures, and subcultures, may socialize us to “turn the other cheek,” whereas others emphasize an “eye for an eye” or not backing down from a fight. Cultures further teach us what responses are appropriate in different situations of frustration or insult. Culture thus has a profound influence on not only the extent of aggression but also the form it can take. We see this influence when we compare national cultures as well as regions and cultural subgroups within a nation.

Comparing National Cultures

Across nations, we find striking differences in prevalence of serious acts of aggression. In the United States, for example, one murder occurs every 31 seconds. This dwarfs the murder rates in other industrialized nations such as Canada, Australia, and Great Britain and is approximately double the world average (Barber, 2006). Although some countries in Eastern Europe, Africa, and Asia have higher rates, much of the violence in those nations is between groups and results from political instability, whereas violent crimes in the United States tend to be committed by individuals against other individuals. Americans have a stronger tendency than people of many other nations to resort to aggressive solutions to interpersonal conflicts (Archer & McDaniel, 1995).

As we noted earlier, the high murder rate in the United States stems in part from the ready availability of firearms (e.g., Archer, 1994; Archer & Gartner, 1984). Firearms not only prime aggression-

450

In trying to understand how and why cultures differ in aggression, some researchers focus on individualism versus collectivism. As we first discussed in chapter 2, individualistic cultures place greater value on independence and self-

Comparing Subcultures Within Nations

Think ABOUT

Imagine that you are walking down a narrow hallway toward your psychology classroom as another student approaches you. As you pass by, you bump shoulders. Apparently prompted by this contact, he mutters “asshole” under his breath before stepping into another room. How would you react? Do you think you might react differently if you grew up in the northern United States as opposed to the South?

Cultures of Honor

Research on regional variations in a culture of honor suggests that the answer might be yes. In places that have a culture of honor, people (especially men) are highly motivated to protect their status or reputations. Daly and Wilson (1988, p. 128) describe it this way:

A seemingly minor affront…. must be understood within a larger social context of reputations, face, relative social status, and enduring relationships. Men are known by their fellows as “the sort who can be pushed around” or “the sort who won’t take any shit,” as people whose words mean action, or as people who are full of hot air, as guys whose girlfriends you can chat up with impunity or guys you don’t want to mess with.

Dov Cohen and Richard Nisbett (Cohen & Nisbett, 1994; Nisbett, 1993) have documented a strong culture of honor in the southern and western United States. For example, homicide rates among White men living in rural or small-

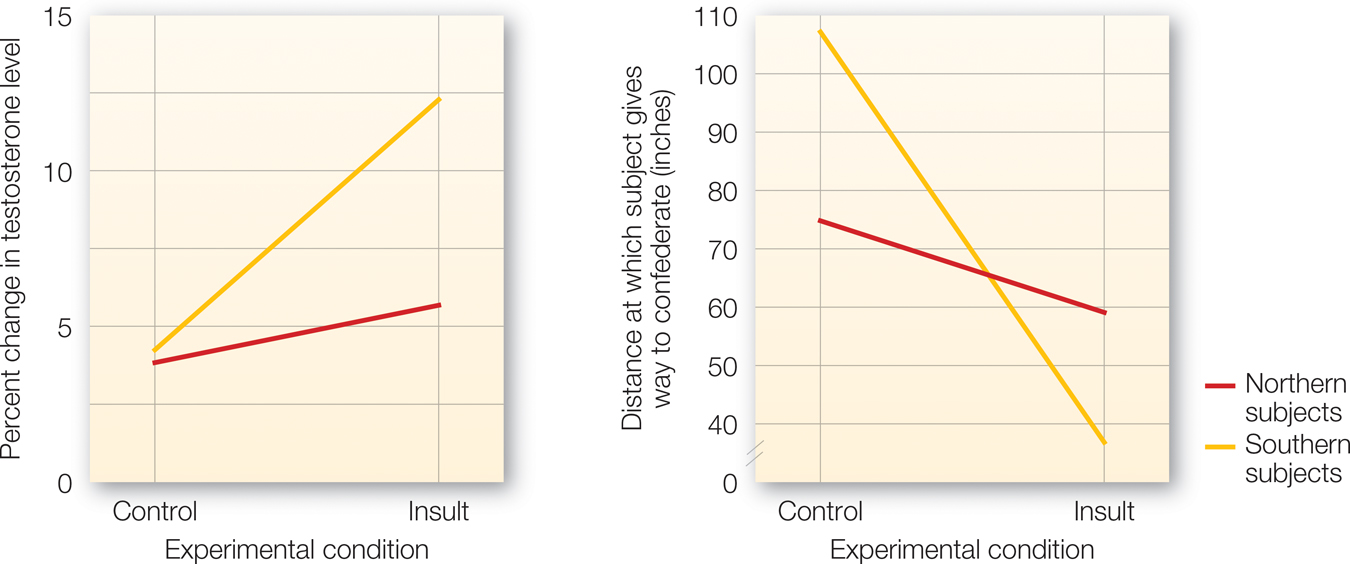

FIGURE 12.10

Culture of Honor

After being insulted, students from the South showed greater increases in testosterone than those from the North, and they were subsequently less likely to back down when approaching another confederate in a narrow hallway.

[Data source: Cohen et al. (1996)]

Recall the example of someone bumping into you in a hallway and then cursing at you for being in his way. Cohen and his colleagues (1996) put unsuspecting male college students from either the North or the South in that very situation. Students from the North did not have much of a reaction to the insult, but students from the South showed comparative increases in aggressive feelings, thoughts, and physiology. They were more likely to think their masculine reputations were threatened and were more upset and primed for an aggressive response, as indicated by higher levels of cortisol, testosterone, and aggressive cognitions. They were also more likely subsequently to engage in dominance-

451

Why did the culture of honor develop primarily in the South and West? Cohen and Nisbett (1994; Nisbett & Cohen, 1996) theorize that the answer goes back to the environmental and economic conditions in the places the American settlers came from and in the regions where they settled. Many southern settlers came from pastoral, herding societies, such as Scotland. Other settlers, who migrated to the arid western regions of the country, became economically more dependent on cattle ranching and sheepherding than on farming. In contrast, the North largely was settled by farmers and developed a more agricultural, as opposed to herding, economy. Because people from a herding-

Herding cultures are associated with cultures of honor.

In addition, because much of the South and West remained frontier land with widely scattered, less effective law enforcement, it became even more important to protect one’s own property. As a result, norms for retributive justice are thought to have developed in the South and West more vigorously than in the North. Similar perceptions and reactions have been observed among participants from Brazil and Chile (Vandello & Cohen, 2003; Vandello et al., 2009), whose cultures also emphasize honor and which have an economic history of herding, but not among Canadians, who are more neutral with respect to honor.

Although these economic and environmental conditions no longer apply, the culture of honor persists, reinforced by institutional norms and scripts of action that people learn through socialization processes and extending to their attitudes and behavior. People from the South have a more lenient attitude toward crimes—

452

Protecting One’s Status

Although cultures of honor might initially develop in societies focused on herding, low-

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

Race and Violence in Inner-

Race and Violence in Inner-

On July 4, 2009, a 16-

On the surface, Terrance Green’s murder seems like another statistic in a larger and disturbing pattern: In the United States, violence is more prevalent in inner-

When you think about gang violence, you probably think about killings between rival gangs over drugs or money. It’s true that Terrance was a gang member and that he was killed by a rival gang. But although these facts about Terrance’s death conform to the general beliefs people have about gang violence, many others do not. For example, children reared in fatherless homes tend to be more violent and aggressive than children in two-

Many social psychological processes lie beneath the cycle of violence (Anderson, 2000). In a place like Englewood, students often don’t join gangs by choice. Instead, the gang you end up in depends on the block you live on. By the time Terrance and his friends hit puberty, they were bullied by older kids for merely walking down a street in another gang’s territory. By default, Terrance was assumed to be part of the gang in his neighborhood, even though he’d never been recruited or agreed to be a member. He was an athlete and a natural leader, so he found himself having to defend his friends as well as himself.

Without knowing what else to do, Terrance and his teenage friends banded together to protect themselves, calling themselves Yung Lyfe (Young Unique Noble Gentlemen Live Youthful and Fulfilled Everyday) —not exactly a name designed to strike fear in the minds of others. Terrance’s father never realized that his son had been backed into being a gang member. And after Terrance was killed, he was shocked to learn that a 23-

Stories like Terrance’s reveal the bind that teens can find themselves in when they live within a gang culture in which many people have guns and aren’t afraid to use them to terrorize others and settle even the smallest of arguments. What would you do in this situation? Maybe you are thinking, Why not go to your parents, your teachers, or the police? Unfortunately, you’d be unlikely to tell them anything they don’t already know. It’s no secret that gang violence is a problem in these neighborhoods. What we are missing are effective solutions. A recent large-

Breaking the cycle of violence in places like Englewood means confronting and looking beyond the racial stereotypes that feed the cycle. Gangs often form in the first place to regulate a market of illegal activities, such as drugs and prostitution. Without ready access to a good education, job training, or job opportunities, illegal behavior can seem like the only choice for survival. As one young Englewood man said in the previously cited interview with Walter Jacobson, “We’ve got to eat. We want to. We want money…. In our neighborhood, I ain’t going to lie to you. [Selling drugs] …. that’s where the money comes from.”

Because neither the police nor the government can regulate these illegal activities, gangs rely on a culture of honor and code of the street to police each other and enforce norms. Once people outside this life start seeing an increased prevalence of gang behavior and violence among members of a specific ethnic or racial group, a stereotyped association of Black = violent begins to form (Dixon, 2008). African Americans are more prevalent in gangs than Euro-

From learning about schematic processing in chapter 4 and stereotyping in chapter 10, we know that once such stereotypes are established, they can bias our perceptions. In a study of prison inmates convicted of violent crimes, those inmates who looked more Black (e.g., darker skin tone and more Afrocentric features) were more likely to have been sentenced to death, even when the crime was as severe as one committed by a White inmate (Blair et al., 2004; Eberhardt et al., 2006). With such strong associations of “Black” with “violence,” self-

As we try to understand the disturbing cycles of violence that plague lower-

453

Gangs

454

The ideas of a culture of honor and the protection of tenuous self-

|

Learning to Aggress |

|

As a species, we excel at social learning, sometimes including how to aggress. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Electronic Media Experimental and longitudinal research shows that watching media violence contributes to aggression. This is especially true when the hero is easy to identify with and is triumphant. Aggressive and frustrated people are more susceptible to the influence of media violence than are others. |

Family Life A violent family life disrupts psychological security and models aggression. Rejected or abused children are more likely to become aggressive themselves. |

Culture Individualistic cultures tend to have higher levels of aggression than collectivistic ones. A culture of honor or code of the street may encourage aggression that is regarded as necessary to protect one’s livelihood or status. |