12.8 Reducing Aggression

It would be an overstatement to say that all types of aggression are bad for individuals and for society in general. The unfortunate truth is that people occasionally intend to block others’ goals or otherwise cause harm. Appropriate expressions of anger and aggression can help a person avoid being treated unjustly (DaGloria, 1984; Felson & Tedeschi, 1993). Also, in many cultures, people value a capacity for and willingness to engage in aggression in military and law-

When this question is put to psychologists and lay people alike, a frequent answer is catharsis, or allowing people to “blow off steam” or otherwise vent their aggressive impulses. These ideas are generally incorrect. Catharsis—

466

What does work? Because aggression has so many causes, there is no easy answer. Nonetheless, theory and research suggest a range of hopeful approaches that target societal, interpersonal, and individual factors.

Societal Interventions

Reduce frustration by improving the quality of life. One way that we can curb aggression is by reducing the prevalence and severity of aversive states that trigger frustration and hostility. We can do this by putting people in other, more uplifting emotional states of mind. In one study, insulted participants were less aggressive if they heard an uplifting song before being given the opportunity to aggress (Greitemeyer, 2011b). Of course, it’s difficult to imagine people listening to uplifting music all the time. There are so many sources of frustration and pain that reducing aversive emotions is a tough challenge. Obvious starting points would be improving the economy and providing healthier and more pleasant living conditions, especially in neighborhoods that are plagued by aggression. Another approach is to teach children prone to be aggressive better problemsolving, communication, and negotiating skills. If they learn these skills, they will experience less frustration in their lives and employ more constructive approaches to dealing with the frustrations that do arise (e.g., Goldstein, 1986).

Gun control. We know that the mere presence of firearms can prime aggressive thoughts and that interacting with guns can boost testosterone, further fueling aggressive behavior. We also know that firearms make aggression more lethal. Therefore, controlling the number and kinds of weapons that are available, and who can obtain them, may not only prevent people from causing unnecessary death and pain but also make it less likely that people’s thoughts turn to aggression in the first place.

Punishing aggression. In most societies, efforts to curb aggression involve punishing aggressive offenders. This can be effective. In one study (Fitz, 1976), participants were less likely to aggress against someone if they knew that they would suffer severe consequences as a result. However, many forms of punishment also model aggression and can increase the recipients’ frustration, thus having the opposite of the intended effect. For example, children who are physically punished at home are more aggressive outside the home later in life (e.g., Gershoff, 2002; Lefkowitz et al., 1978). Given these conflicting findings, researchers have investigated the specific conditions under which punishment is effective (Baron, 1977; Berkowitz, 1993). To be effective, punishment must be: (1) severe (without modeling aggression); (2) delivered promptly, before the aggressors benefit from or change their behavior; (3) perceived as justified; and (4) administered consistently. The American legal system rarely meets criteria (2) and (4) (Goldstein, 1986), thereby limiting the system’s deterrent value. A long process intervenes between arrest and sentencing. Laws and sentencing are often inconsistent within and between states. For example, activities such as gambling, prostitution, and marijuana consumption are legal in some states but can result in prison sentences in others.

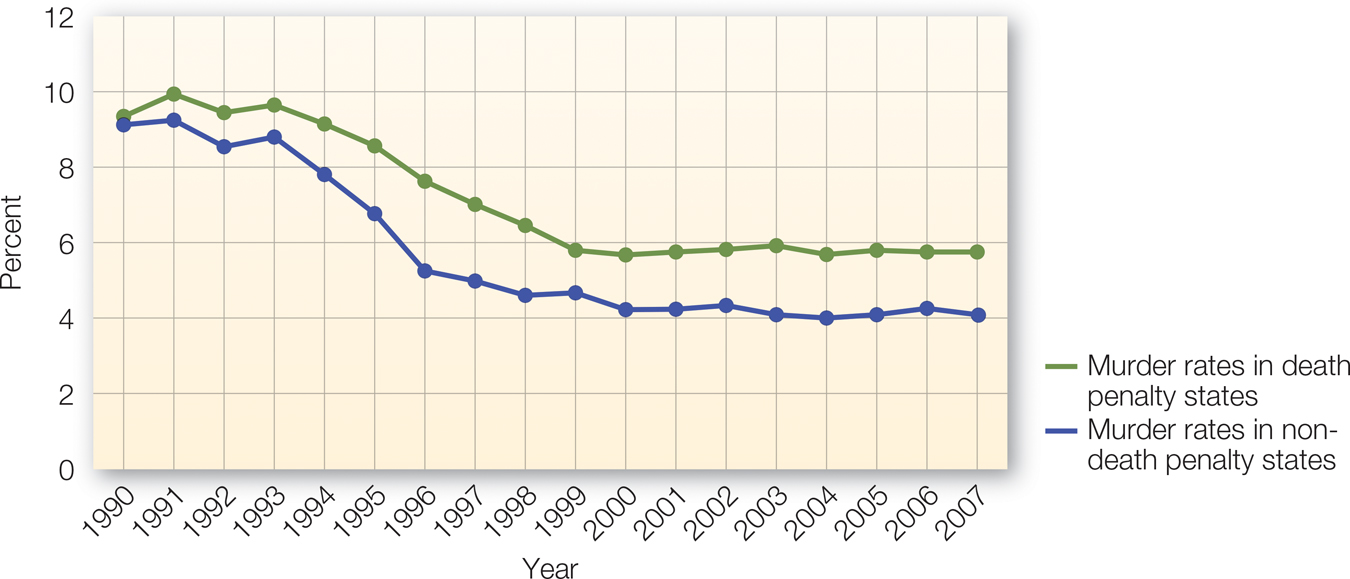

FIGURE 12.12

Murder Rates in States With and Without the Death Penalty

The death penalty is intended as both punishment and deterrent, but statistics show that murder rates are higher in those states with the death penalty than in those without it.

[Data source: Goldstein (1986)]These criteria also help explain why the death penalty has not been effective in deterring violent crime. In fact, as FIGURE 12.12 shows, murder rates tend to be higher in states with the death penalty than in those without it. When the death penalty is introduced, the murder rate actually tends to increase (Goldstein, 1986). Capital punishment makes aggression salient and communicates the idea that killing is sometimes justified. Executions tend to happen many years after the murder that they are intended to punish. Thus, the link between the actions and the punishment is temporally remote. In addition, most murders are committed in a fit of rage when people are unlikely to be thinking of consequences.

467

What forms of treatment would work to decrease violence in an individual? One promising alternative approach is multisystematic therapy (Borduin et al., 2009; Henggeler et al., 1998), which addresses what drives individuals to aggress in specific contexts in which they are embedded, such as school and neighborhood. Courses and other training programs that focus on rehabilitation, as opposed to deterrence or retribution, also hold greater promise. But American penal institutions spend very few of their resources on rehabilitation (Goldstein, 1986), a fact that probably contributes to the high recidivism rate. Half or more of inmates released from U.S. prisons in a given year end up returning for another stint (Goldstein, 1986; Bureau of Justice Statistics, n.d.).

Reduce or reframe media depictions of aggression. With all the evidence that exposure to violence in the media can prime and model violent thoughts and actions, we might reduce aggression by minimizing people’s exposure to such media depictions. Of course, censorship carries its own costs, but there is no question that American society can do a better job of limiting exposure of young children to violence in the media. Another approach is to direct people to media that model prosocial behavior or depict the negative consequences of aggression. The media frequently portray people as benefitting from aggressive behavior. Viewing such portrayals increases aggression. In contrast, exposure to scenes showing punishment of aggressive behavior inhibits viewers from aggressing (Betsch & Dickenberger, 1993). Just as playing violent video games can increase aggressive cognitions and behavior, playing prosocial video games decreases hostile attributions and aggressive cognitions (Greitemeyer & Osswald, 2009). The more children play prosocial video games, the more they also engage in prosocial behavior (Gentile et al., 2009). Thus, there is potential for reducing aggression in exposing people, and especially children, to different types of media depictions.

Another alternative approach is to educate people about how to interpret violent media depictions. Rosenkoetter and colleagues (2009) designed a 7-

month media literacy program in which children were encouraged to distinguish between “pretend” aggression and aggression in the real world, and to choose prosocial models to admire and imitate. Children who took part in this program were less willing to employ aggression after being exposed to media depictions of aggression (Byrne, 2009). Incorporating media- literacy courses into school curricula may help counteract aggression- promoting media influences.

468

Interpersonal Interventions

Improve parental care. People can learn to be better parents. Training parents in more effective methods of raising their children often leads to a reduction in aggressive and antisocial behavior in the children (Patterson et al., 1982). Training juvenile offenders and their parents to communicate better with each other helped to reduce violent activity among the aggressive youth (Goldstein et al., 1998). Given that most children will eventually become parents, why aren’t courses on appropriate parenting routinely included in school curricula?

Strengthen social connections. A greater sense of communal connection, more cooperation and less competition, and fewer experiences of social rejection would reduce aggression in society. Improving people’s social skills is likely to lead to more positive social interactions and has been shown to be effective in reducing aggression in children (Pepler et al., 1995). Connecting with others, even if only briefly, helps to reduce aggression that stems from feeling rejected. For example, Twenge and colleagues (2007) gave participants the opportunity to have a short, friendly interaction with the experimenter (as opposed to a neutral interaction) after being rejected socially and found that these participants subsequently showed lower levels of aggression. This friendly interaction helped to restore the rejected participant’s trust in others. The more participants trusted others, the less aggressive they were.

Enhance empathy. Aggressive behaviors such as threatening, attacking, and fighting with others seem to reflect a low awareness of or concern for the pain and suffering that other people experience. Empathy is the ability to take another person’s point of view and to experience vicariously the emotions that he or she is feeling. Results of many studies conducted with children and adults document an inverse relationship between empathy and aggression (Richardson et al., 1994). This is true both when empathy is assessed as an individual difference variable and when empathy is experimentally induced by instructing individuals to imagine how another person feels. Programs that teach juvenile delinquents how to take other people’s perspective also have been found to be beneficial (Goldstein, 1986).

Individual Interventions

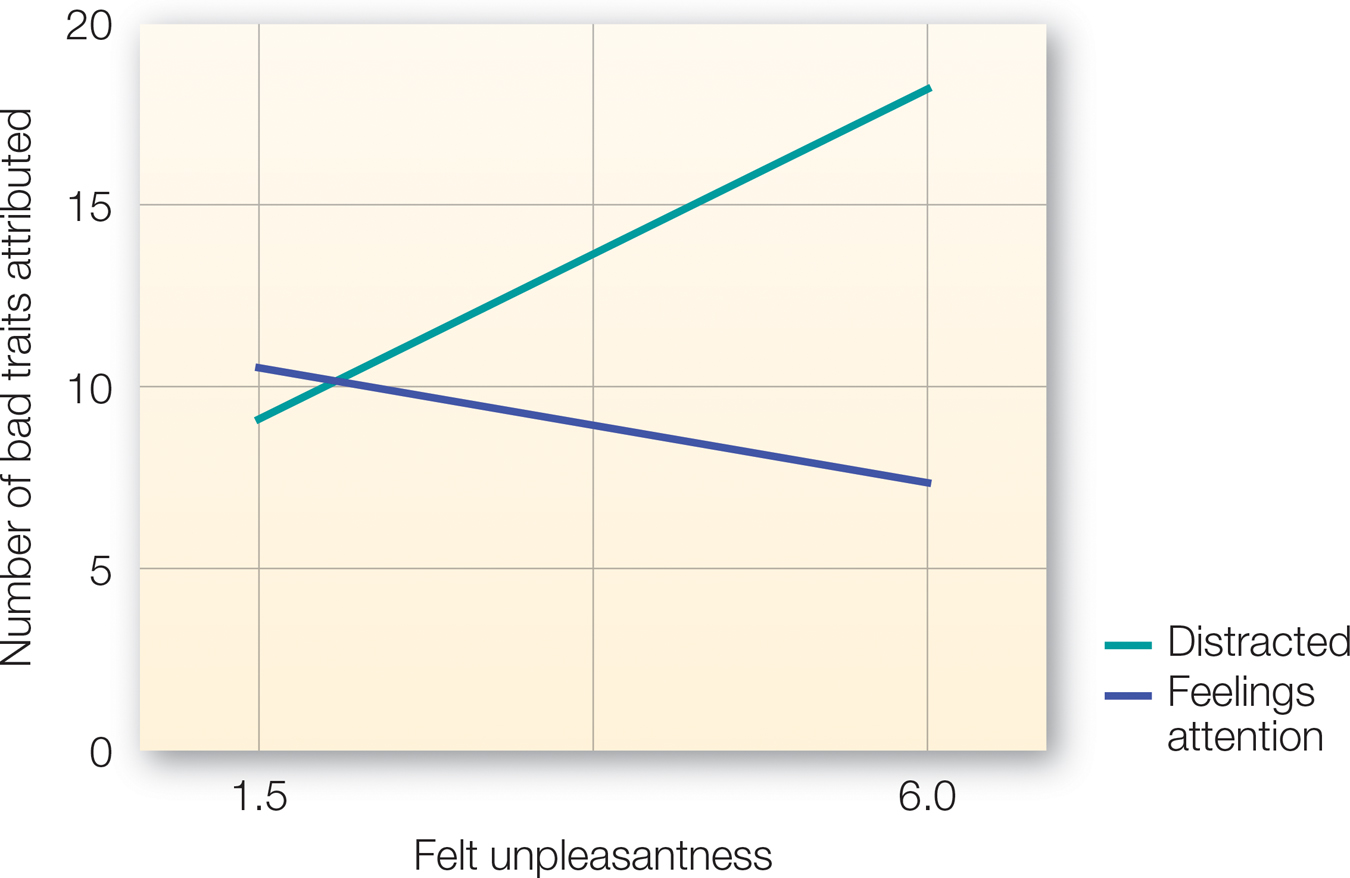

FIGURE 12.13

Self-

awareness of Feelings and Aggression

If people focus their awareness on their feelings, they are less likely to view others negatively. This is one promising avenue toward reducing aggression.

Data source: Berkowitz & Troccoli (1990)]Improve self-

awareness . Berkowitz proposed that people can become aware of what makes them feel unpleasant or stressed and that they can choose not to let that distress trigger aggressive behavior. In addition, self-awareness tends to bring internalized morals and standards to mind and increase their influence on behavior. The effectiveness of such self- awareness is demonstrated in a study by Berkowitz and Troccoli (1990). Participants were put through an uncomfortable physical activity or not. Half the participants in each of these conditions were then distracted with an irrelevant task, whereas the remaining participants were asked to attend to their inner feelings. Immediately afterward, all participants rated another student’s personality. As you can see from FIGURE 12.13, when participants were distracted, the more discomfort they felt, the more unfavorably they rated the target. In contrast, those participants prompted to attend to their emotional states did not verbally aggress, and even became more reluctant to say negative things about the target person (perhaps in an effort to be fair and correct for the possible distorting influence of their negative mood). Increase self-

regulatory strength . If we can improve people’s self-regulatory abilities, they will be better able to control their aggressive impulses. This can be facilitated by reducing the prevalence of factors that inhibit self- awareness and self- control, such as alcohol use, environmental stressors such as noise, and conditions that foster deindividuation (described in chapter 9). In addition, we can increase self-

regulatory strength by helping people to practice controlling their behavior. In one study (Finkel et al., 2009), participants who took part in a 2- week regimen designed to bolster self- regulatory strength (e.g., by brushing their teeth with the nondominant hand or by making sure that they did not begin sentences with “I”) reported a reduced likelihood of being physically aggressive toward their romantic partner. Teach how to minimize hostile attributions. Hudley and Graham (1993) developed a 12-

week program designed to prevent aggressive children from lashing out by reducing their tendency to attribute hostile intent to others. Through games, role- play exercises, and brainstorming sessions, they taught children about the basic concepts of intention in interpersonal interactions and helped them to decide when someone’s actions (e.g., spilling milk on them in the lunchroom) are deliberate or accidental. Compared with boys who went through an equally intensive program that did not focus on attributions of intent, boys who received the attribution training were less likely to presume that their peers’ actions (real and imagined) were hostile in intent, they were less likely to engage in verbally hostile behaviors, and they were rated as less aggressive by their teachers. Improve people’s sense of self-

worth and significance . When people have high, stable self-esteem, they respond to threats with lower levels of hostility and anger (e.g., Kernis et al., 1989). One source for such a foundation is a stable, secure attachment with a close other. Indeed, studies show that, among troubled and delinquent adolescents undergoing residential treatment programs, those who formed secure attachment bonds with staff members exhibited less aggressive and antisocial behavior (Born et al., 1997). More broadly, a society that provides a wide range of attainable ways of developing and maintaining self- esteem should foster less aggressive people.

|

Reducing Aggression |

|

Aggression has many causes, so there is no single, easy way to reduce its prevalence. However, some approaches do inspire hope. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Societal interventions Large- improve quality of life. better control access to weapons. punish aggression more effectively. better address media violence. |

Interpersonal approaches Improve parental care. Strengthen social connections. Promote empathy. |

Individual approaches Improve self- |

CONNECT ONLINE:

Check out our videos and additional resources located at: www.macmillanhighered.com/