13.1 The Basic Motives for Helping

Before we begin, let’s define what we mean by prosocial behavior. Prosocial behavior is action by an individual that is intended to benefit another individual or set of individuals. Defined in this way, many of the actions of artists such as Vincent van Gogh, actors such as Meryl Streep, entertainers such as Beyoncé, scientists such as Louis Pasteur, and political figures such as Martin Luther King, Jr. can be considered prosocial behavior. Many people have benefited from the artistic creations, scientific discoveries, and social changes initiated by such esteemed individuals whether they starred in our favorite movies, developed life-

Prosocial behavior

An action by an individual that is intended to benefit another individual or set of individuals.

Vincent van Gogh painted The Potato Eaters to draw attention to the struggles that ordinary people face in their daily lives.

[Art Resource, NY]

Although it is important to acknowledge these forms of prosocial behavior, theory and research on prosocial behavior generally have not focused on people with extraordinary talent. Instead, most of this work studies the factors that influence whether ordinary people choose to help or not help each other from day to day. Sometimes the kind of help people give is quite minor, such as stopping to help someone pick up a bag of groceries that has spilled. Other times, it can be much more dramatic, such as providing CPR to someone who has collapsed. Some instances of helping come at personal cost or physical risk. Other times, the person giving help benefits as much, if not more than, the person receiving help.

473

Psychologists often take it as an assumption that people’s actions are motivated primarily by some degree of self-

However, being social animals, we don’t care only about ourselves. We also genuinely care about those with whom we form emotional attachments—

Altruism

The desire to help another purely for the other person’s benefit, regardless of whether we derive any benefit.

Dramatic examples of altruism occur when people risk their lives to help unrelated others. During the Nazi occupation of Europe, a substantial number of non-

Human Nature and Prosocial Behavior

If you take an evolutionary perspective on human behavior, you might think that people who risk their lives to save others from the Nazis, or who throw themselves into raging rivers to save a stranger, are acting very strangely. After all, a core assumption of evolutionary theory is that species evolve new traits and behavioral tendencies when those attributes benefit the propagation of an organism’s genes to the next generation. We might therefore expect people to care only about their own well-

474

Kin Selection: Hey, Nice Genes!

A propensity for helping close relatives, or kin, may have been selected for over the course of hominid evolution. The idea that natural selection led to greater tendencies to help close kin as opposed to those who are less genetically related is known as kin selection (Hamilton, 1964). The principle underlying kin selection is that because close relatives share many genes with an individual, when the individual helps close kin, those shared genes are more likely to be passed on to offspring. In this way, genes promoting the propensity for helping close kin become more prevalent in future generations. In support of this idea, people report that they are more likely to help another person the closer their genetic relationship (Burnstein et al., 1994). Regardless of whether they are risking their lives or merely lending a hand, people report being more helpful to parents and siblings than to cousins, aunts, and uncles. Also, they are more likely to help distant relatives than acquaintances or strangers. What’s more, these findings hold up across very different cultures (Madsen et al., 2007).

Kin selection

The idea that natural selection led to greater tendencies to help close kin than to help those with whom we have little genetic relation.

Although the idea of kin selection is popular with evolutionary psychologists and some biologists, its role in human prosocial behavior is difficult to isolate. Cultures invariably teach people that they are obligated to help close relatives, so we don’t know how much of the preference for helping close kin is innate and how much culturally learned. In addition, it is important to acknowledge that many examples of human helping cannot be explained by kin selection. These include devoted parents who raise adopted children; people from developed countries who give to charities such as CARE and UNICEF; individuals who would more readily help a good friend than a disliked first cousin; and good Samaritans, who, at great personal risk, help complete strangers and unrelated friends.

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

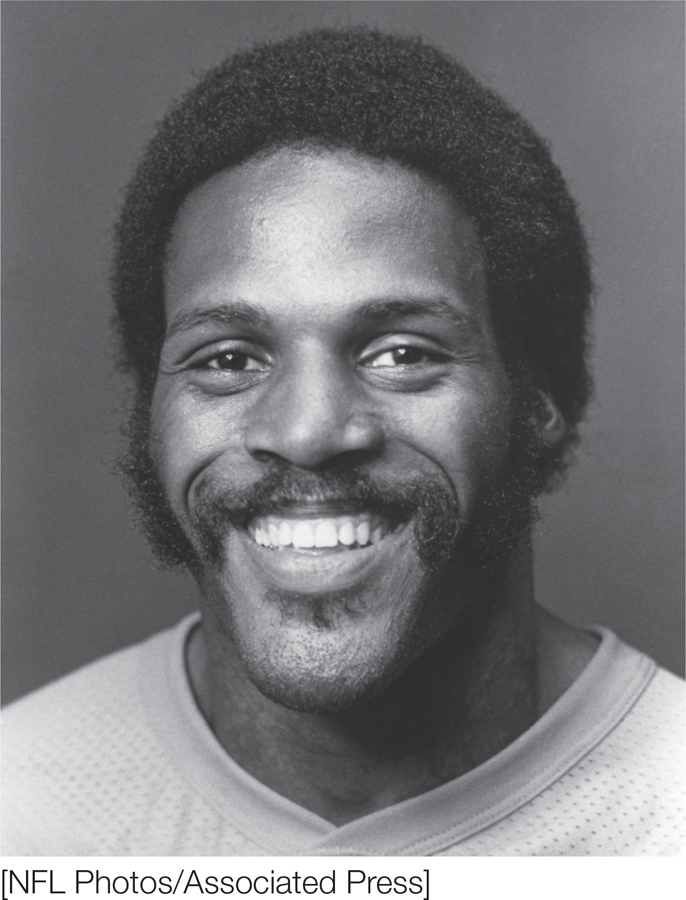

A Real Football Hero

A Real Football Hero

During the 1980s, Joe Delaney was a star running back, jersey no. 37 for the NFL’s Kansas City Chiefs. Many thought he was on his way to a Hall of Fame career. In 1983, he was the best young running back in the American Football conference. He was also happily married with three young daughters. However, his bright future was cut tragically short by his own heroic actions (Reilly, 2003; Chiefs Kingdom: Joe Delaney, Sept 28, 2013; http://www.kcchiefs.com/media-

On a hot and sunny afternoon on June 29, 1983, Joe Delaney was relaxing at a park in Monroe, Louisiana. After hearing cries for help from a nearby pond, he bounded into action. Three young boys had waded into the pond to cool off in the hot Louisiana sun. The boys included two brothers, Harry and LeMarkits Holland, and their cousin Lancer Perkins, all aged 10 or 11. None of them knew how to swim, but they had unexpectedly stepped into deep water and were struggling to stay above the surface. Joe did not stop to consider if someone else should be attempting this rescue. Although he knew that his own swimming skills were weak, Joe felt an immediate obligation to try to save these children. He managed to grab LeMarkits just as water began to enter the boy’s lungs, saving his life. But his attempt to save the other two failed, and the boys and Joe drowned.

The park was crowded that day with people enjoying the summer afternoon, but only this man celebrated for his speed and agility rushed into action. In a documentary on the event, Deron Cherry, Delaney’s teammate, described Joe’s heroic actions that day, “You ask yourself, what would you do in that situation? And if you have to think about it, then you know you are not going to do the right thing. But he never thought about it. The thing that was on his mind was, ‘I need to save these kids.’” (Chiefs Kingdom, September 28, 2013).

As you will learn in this chapter, crowds of people can often immobilize people from stepping up to help. But Joe Delaney’s story offers a powerful exception to the rule. People do sometimes help others at extraordinary costs to themselves. Joe even continued to help kids after his death. A foundation started in his honor, The 37 Forever Foundation, spent the next two decades offering free swimming lessons to children (Reilly, 2003).

Sociability, Attachment, and Helping

Why do people like Joe Delaney (see Social Psych Out in the World) help when it clearly doesn’t serve their interests to do so? One key answer is that our evolutionary history likely selected for a general proclivity to be helpful. This inherited propensity can lead to behaviors that sometimes will prevent the transmission of an individual’s genes, even though on average, across people and situations, they may have adaptive value. As we noted in chapter 2, our hominid ancestors lived in small groups in which members were successful by caring about others: emotionally attaching to them, caring for and cooperating with them, fitting in with the group, trying to be liked and to live up to internalized morals. These bonds with others are associated with an innate capacity to experience certain emotions that foster helping: sympathy, empathy, compassion, and guilt. Thus, prosocial behavior arises from our evolved proclivities for sociability and forming close attachments and the emotions these proclivities arouse. They are the bases for the human propensity to engage in prosocial behavior. We help because we care.

475

Reciprocal Helping

Evolutionary psychologists have suggested another explanation of why helping is such a prominent aspect of human behavior. Recall that we’ve already covered some of the surprising examples of what humans can achieve through cooperation (see chapter 9). In fact, cooperation itself can be viewed as a form of prosocial behavior. Cooperating with others for a common goal or to combat a common enemy means placing a certain amount of trust in someone else. If I help you today, you might be more likely to help me tomorrow, and that, my friends, could give me a genetic advantage over the grumpy lout who never does anything for anyone else. This pattern of you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours is referred to as the norm of reciprocity. Evolutionary theory suggests that patterns of reciprocity can provide individuals or even groups with an adaptive advantage (Trivers, 1971).

Norm of reciprocity

An explanation for why we give help: if I help you today, you might be more likely to help me tomorrow.

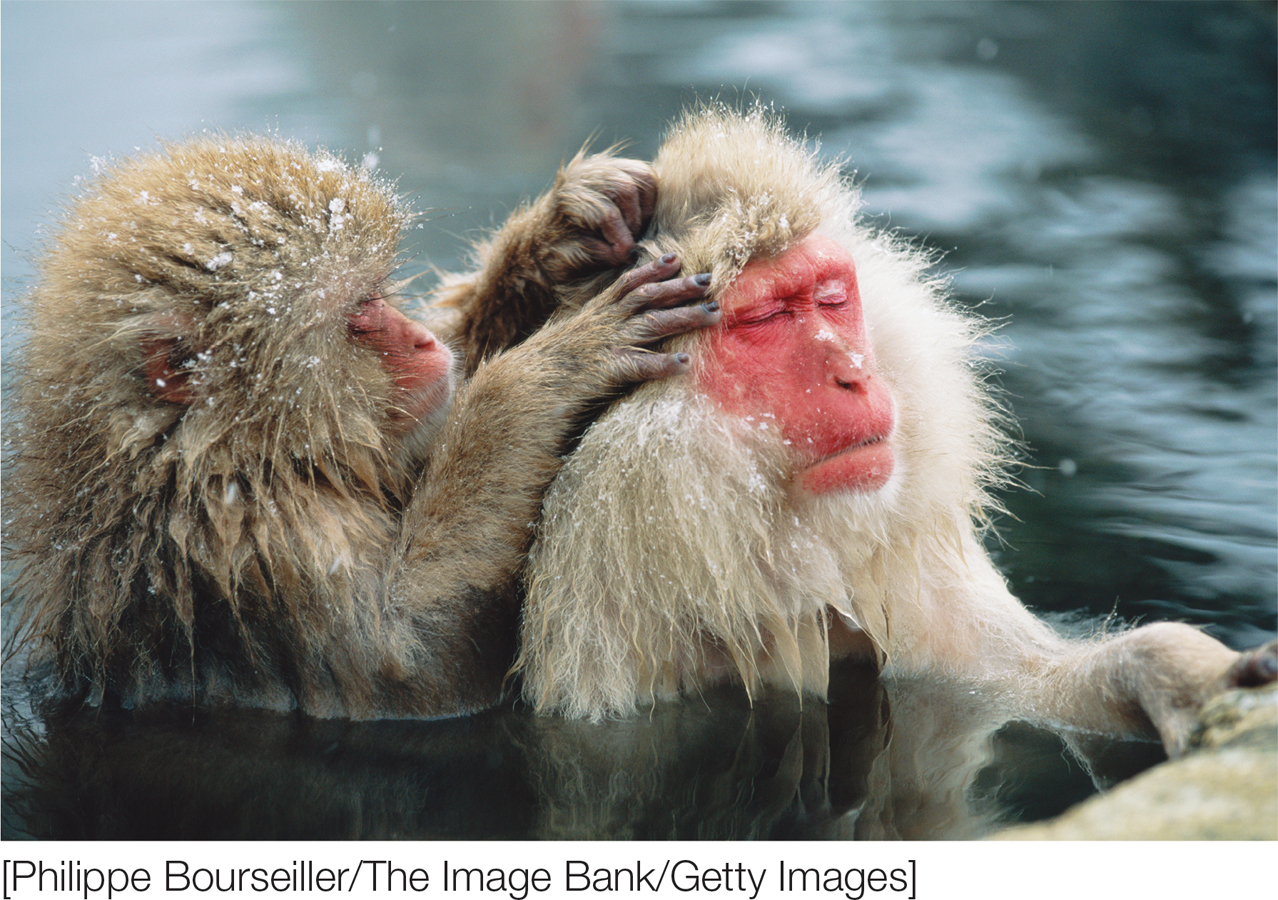

Reciprocal helping can be found in numerous animal species, including in (as we noted in chapter 7) vampire bats, impalas, capuchin monkeys, and chimps (Brosnan & de Waal, 2002). For example, if baboon A grooms baboon B, baboon B is more likely to share food later with baboon A. In humans, feeling obligated to return favors seems to be pretty automatic. We even feel the need to reciprocate and return favors to people we don’t like (Regan, 1971). Humans are also generous to others when the likelihood that they will reciprocate is low (Delton et al., 2011) and even without a tit-

476

Biological Bases of Helping

Many social species engage in reciprocal helping. If you pick the bugs out of my fur, I’ll pick the bugs out of yours.

[Philippe Bourseiller/The Image Bank/Getty Images]

If helpfulness does indeed have a genetic basis, there should be some evidence of gene-

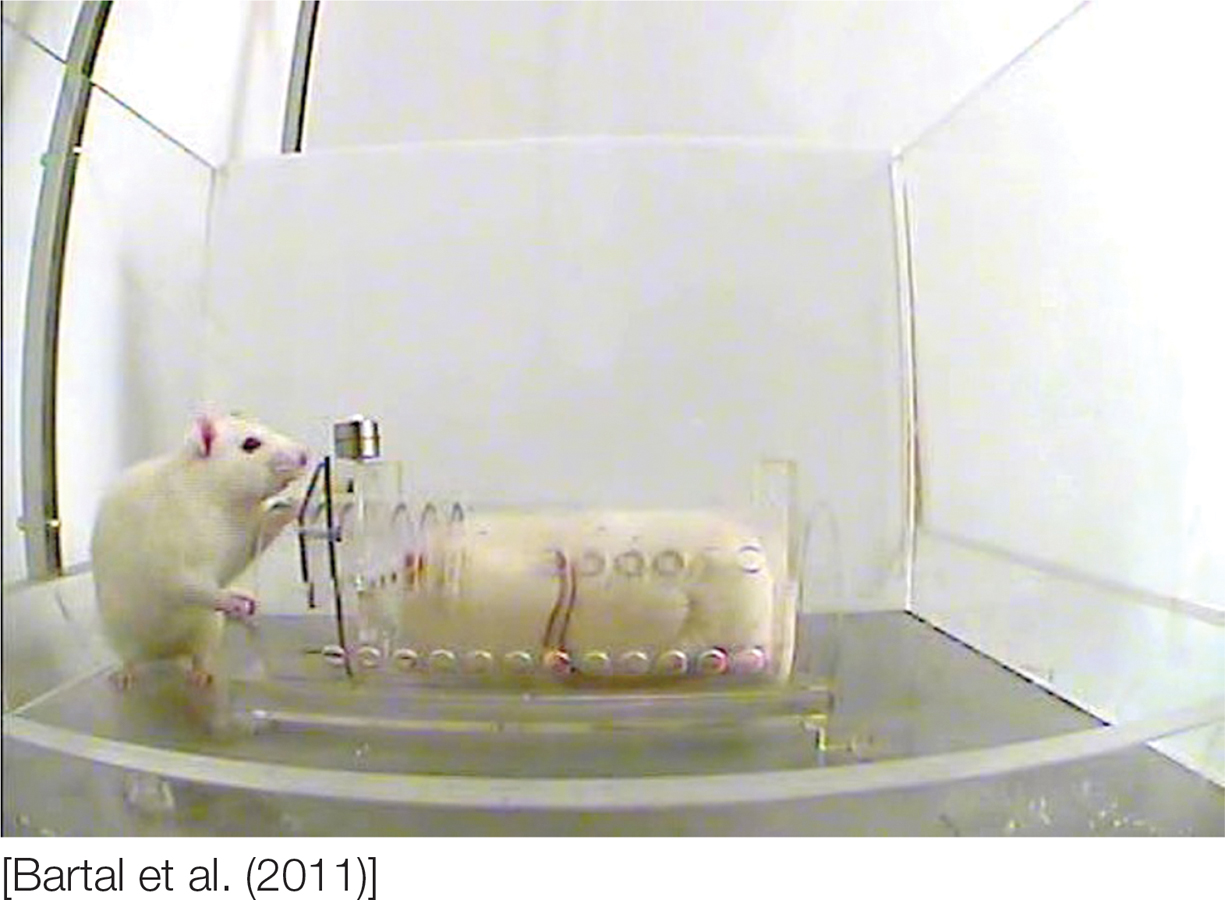

As shown in laboratory research by Bartal and colleagues (2011), even rats will work to free a trapped cage mate without prior learning or obvious reward.

[Bartal et al. (2011)]

Other evidence suggestive of a biological basis for helpfulness can be found in the study of other social animals. Chimpanzees will help out their human caretaker by getting something that she cannot reach (Warneken & Tomasello, 2006). They will also share food with other chimps and will help other chimps who have helped them in the past or with whom they have formed friendships or alliances (Brosnan & de Waal, 2002). Such examples of helping are not confined to primates. Scientists monitoring a group of killer whales near Patagonia observed that when an elderly female had damaged her jaw and could not eat properly, she was fed and kept alive by her companions (Mountain, 2012). Similarly, in an experiment, rats who first shared a cage with another rat for a couple of weeks worked to free their cage mate when they found he was trapped behind a closed door (Bartal et al., 2011). Without any prior learning about how to open the door or any clear reward for doing so, the rats figured out how to free their buddy. If a pile of delicious chocolate chips was placed behind a second closed door, the rats were as likely to free their cage mate as free the chocolate chips. And when both doors had been opened, the two rats tended to share the chocolate. Who knew rats could make such good roommates! Of course, nonhuman animals are occasionally stingy, keeping food for themselves even when another is visibly begging for a snack (Vonk et al., 2008), but a good deal of evidence shows that species other than humans can and do engage in prosocial behavior.

If prosocial behavior is an inherent part of our human nature, then we might see evidence of it at a very young age. In fact, babies have a pretty keen sense of who’s naughty and who’s nice. Infants as young as 3 months prefer others who are helpful rather than hurtful (Hamlin et al., 2007, 2010; Hamlin & Wynn, 2011). If we come into the world ready to evaluate people on the basis of their good or bad behavior, perhaps we come preequipped to carry out good behavior ourselves. Toddlers less than two years old will help an experimenter pick up something she has dropped (Warneken & Tomasello, 2006). What’s more, the toddlers did not help simply because they were interested in picking stuff up when it fell. They picked up the fallen item only if it seemed to have been dropped by accident, and not when the experimenter intentionally dropped it. Young kids do not help just anyone but selectively help those who have been helpful in the past (Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, 2010). These early examples of helping also might reflect a motive to affiliate with others. Even 18-

477

Learning to Be Good

When they are quite young, children show a desire to help others.

[Yuri Arcurs/Getty Images]

Humans are no doubt genetically predisposed toward helping, but we also are predisposed to learn and so develop helpful tendencies through the socialization process. Positive parenting practices, for example, predict greater prosocial behavior in children even after controlling for any shared genetic relationship (Knafo & Plomin, 2006). Although genes provide people with some basic inclinations, culture and learning shape when and for whom these inclinations are cued. Indeed, among the most important genetic inheritances we humans share is the enormously flexible capacity for learning and internalizing local morals and social norms (Becker, 1962; Hoffman, 1981). In this way, people’s prosocial behavior is jointly influenced by both genes and environment (Eisenberg & Mussen, 1989; Knafo et al., 2011).

A learning-

As cultural animals, people are saturated with information that can cue ways of being and behaving. These include parents, teachers, role models, and media. Some prosocial instruction is fairly explicit. At a young age, children are taught to share with siblings and playmates. They might be given chores to do around the house to teach them ways that they can help the family. In an effort to extend the prosocial orientation beyond close family and friends, many elementary and secondary schools offer programs to encourage community service or fund-

Just as children learn specific behaviors and acts of charity from the people around them, so too do these people influence children’s emotional responses to those in need. For example, parents who display more emotional warmth themselves tend to have children who are better able to empathize with others and who are seen by others as more socially competent (Zhou et al., 2002). These relationships are present even after researchers controlled for the empathy these children displayed during a study two years previously, underscoring the causal role that parents might be playing. Children also can learn to be more prosocial if they are encouraged to integrate helpfulness into their personal identities. In one study, second graders who were labeled helpful when they shared were more likely to be helpful later than those who shared but weren’t labeled helpful (Eisenberg et al., 1987).

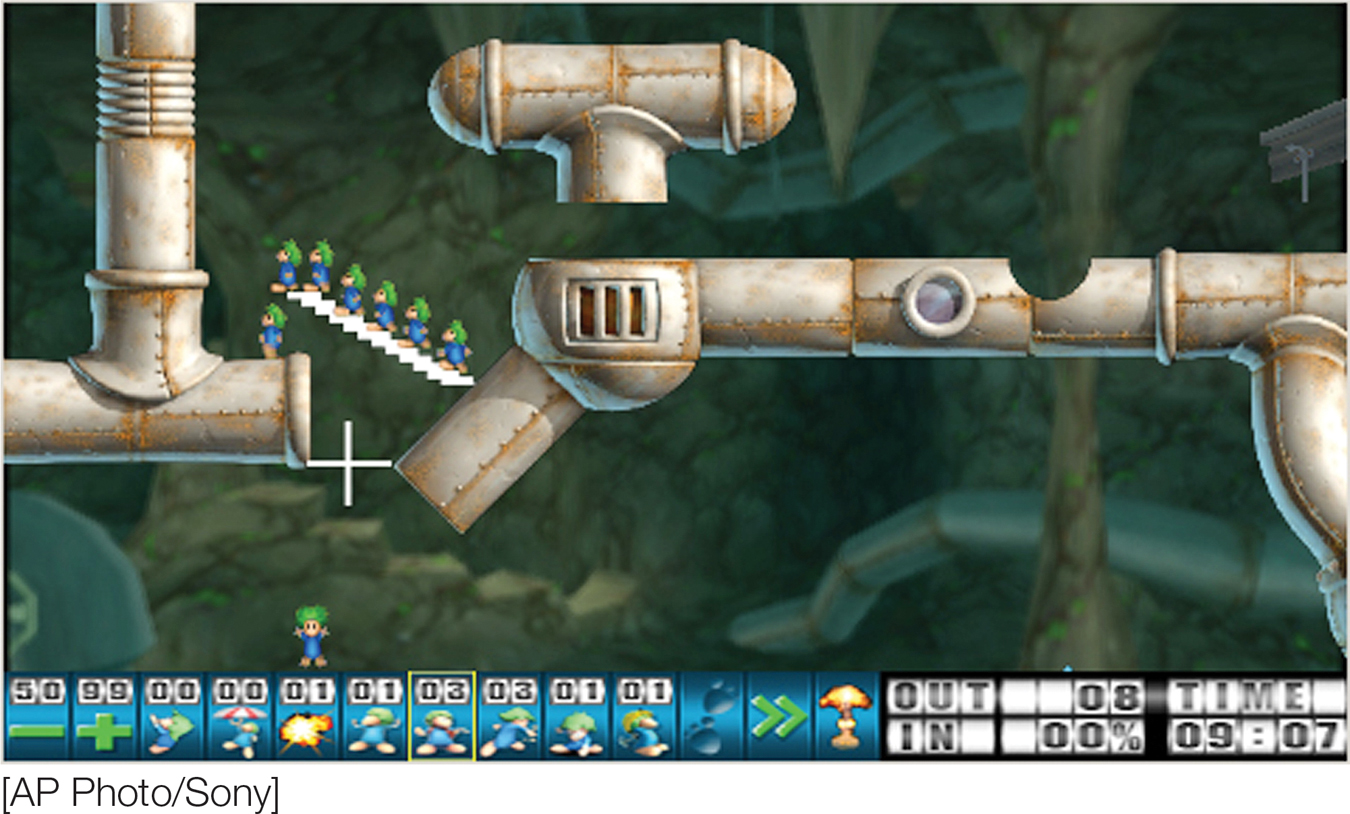

Practicing helping can make you more prosocial. Immediately after people play the video game Lemmings, which requires them to keep the little lemmings from leaping to their deaths, they are more helpful to other people.

[AP Photo/Sony]

478

People also learn prosocial tendencies from the media. Consider video games. In chapter 12 we saw that violent video games can encourage aggressive responses. Yet playing video games that reward prosocial behaviors increases prosocial behavior (Greitemeyer, 2011a). When study participants first played Lemmings, a video game whose primary goal is to keep your little group of lemmings alive, they were later almost three times more likely to help the experimenter pick up spilled pencils than were those who had played Tetris. Of course, picking up pencils poses no great sacrifice. But what about a more dangerous situation? When the experimenters constructed a scenario in which the participants witnessed the female experimenter being harassed by her hostile ex-

|

The Basic Motives for Helping |

|

Prosocial behavior is an action by an individual that benefits another. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Genetic influences People may be helpful because prosocial behavior might have been generally adaptive in the history of our species. Although the propensity for helping is especially strong among close kin, it is not restricted to them. Prosocial emotions contribute to helping. Norms of reciprocity contribute to prosocial behavior, even among strangers. Research with twins, toddlers, and nonhuman animals points to an inherited biological basis of prosocial behavior. |

Learned behavior Parents greatly influence prosocial behavior in children. Children learn prosocial behavior in stages: to get things (such as gold stars), for social rewards, and to satisfy internal moral values. Media can encourage prosocial behavior by making helping- |

|