13.5 Why Do People Fail to Help?

We like to think of ourselves as good, moral people, capable of empathy and compassion. Prosocial behavior benefits our relatives, friends, and groups; materially benefits victims; and psychologically benefits ourselves. At this point, we might expect that being helpful will always be the norm. But we can probably think of times when we passed by a panhandler without giving him money, closed the door on a solicitor seeking donations for a local charity, or made excuses to a friend looking for a ride to the airport. The fact of the matter is that we don’t always give or receive help. The flip side of looking at variables that elevate our helpful tendencies is to consider those that inhibit helping.

The Bystander Effect

Kitty Genovese was brutally murdered in 1964. News accounts claimed that witnesses heard the attack take place but did not help, spurring researchers to study the bystander effect.

[NY Daily News via Getty Images]

We began this chapter with dramatic examples of helping. But during the Nazi era, for every rescuer who helped Jews avoid persecution, there were many, many more people who did nothing—

In the early morning hours on a cold day in March, Kitty Genovese returned home after work. As she walked toward her apartment building in Queens, New York, she was attacked from behind and stabbed in the back. The perpetrator continued to assault and stab her in a brutal attack that lasted over 30 minutes. During this time, Genovese cried for help, screamed that she had been stabbed, and tried to fight off her assailant. A New York newspaper reported that 38 people had witnessed the attack from their apartment windows and yet no one called the police until after the attack had ended. Unfortunately, by then it was too late. Genovese died on the way to the hospital (Gansberg, 1964).

At the time, people took this horrific episode as evidence of the moral disintegration of New Yorkers—

Bystander effect

A phenomenon in which a person who witnesses another in need is less likely to help when there are other bystanders present to witness the event.

494

To see how this works, put yourself in the shoes of one of Darley and Latané’s (1968) participants. You think you are going to be having a conversation over an intercom system about the challenges of being at college. You learn that it will just be you and another student, or that you will be part of a group of either three or six. To protect everyone’s privacy, you are each in your own room, only able to hear the others over the intercom. As the discussion gets under way, one of the other participants discloses his history of having seizures and talks about how disruptive and stressful it can be. You are also asked to share something about your experience, as are the other participants if you are part of a group. After another round of sharing, the student who had complained of seizures seems to be having one. The transcript of what people actually heard included:

I-

Clearly, this person is having a hard time and is explicitly asking for help. If you were like the students who participated in this study over 40 years ago, you probably would get up to find the experimenter if you thought you had been having a private conversation with this person. Every single participant in that condition got up to help, and 85% of them did so within a minute and before the victim’s apparent seizure had ended. When participants believed instead that four other people were listening, only 31% tried to help by the time the seizure had ended.

In another study (Latané & Darley, 1968), participants completed questionnaires in a waiting room, either alone or with two others who were sometimes confederates of the study or sometimes other naive participants. As they dutifully answered surveys, smoke began to stream into the room through a wall vent. In the group condition, the two confederates both looked up at the smoke briefly and then went back to their questionnaires. If participants were alone, 75% of them got up and alerted the experimenters to the smoke. But this dropped to less than 40% when three naive participants were in the room, and only 10% if the participant sat alongside confederates who remained inactive.

A recent meta-

Steps to Helping—or Not!—in an Emergency

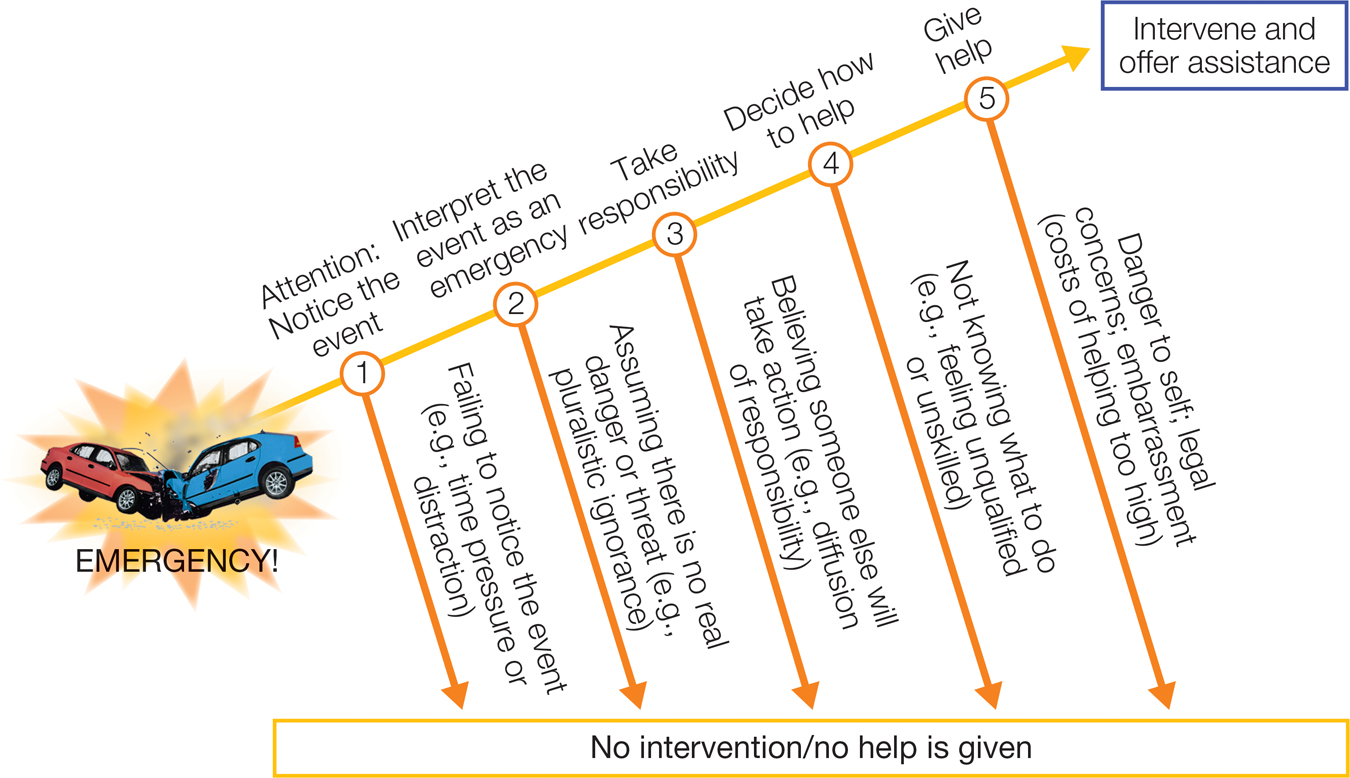

FIGURE 13.2

Steps to Helping . . . or Not

When encountering a potential emergency situation, people must take multiple steps in deciding whether to offer help. At each step, we can make a judgment about ourselves or the situation that prevents us from helping.

What is it about being in a group that immobilizes us? When we break down an event into its component parts, we can see that the decision to provide help in an emergency situation requires several steps. As a result, there are several places and several reasons that people don’t always get the help they need. FIGURE 13.2 presents several steps leading to helping behavior. At each step, something in the situation can waylay the process, causing us to keep walking and ignore others in need.

495

Step 1: Notice the situation. The first step on the path to helping is to notice that something is amiss and that help might be needed. Although the seizure study clearly was designed to make the victim’s plight quite obvious, in the real world we often go about our day immersed in our egocentric bubble and somewhat oblivious to the needs of those around us. We don’t like to think that something as simple as being rushed for time would prevent us from offering assistance to someone in need. But this is exactly what Darley and Batson (1973) found in one intriguing experiment that was designed to provide the strongest test that situational factors can prevent people from acting on their moral values. For their study, the researchers recruited people they thought surely would be the most compassionate folks around—

After rehearsing this story of goodwill and compassion, these practiced preachers were sent to another building where they would give their sermons. The experimenter explained either that they had plenty of time to get there or that they were running late. As these unwitting participants followed a map to the assigned location, they passed a person hunched over and moaning in a doorway. In other words, these ministers in training encountered a modern-

496

Step 2: Interpret the situation as an emergency. Assuming that you notice that something is not quite right, stepping in to provide help requires you to interpret the event as one in which help is needed. In the Kitty Genovese case, a dozen people reported hearing yelling, but most of them actually interpreted it as a lover’s quarrel rather than a murderous attack. Likewise, if you were in the study where smoke started wafting through an air vent, you would also probably feel uncertain of whether this was cause for alarm. So what does this have to do with the bystander effect? If you recall our discussion of informational social influence in chapter 7, you’ll remember that when situations are ambiguous, we take our cues from other people. If they aren’t taking any action, we take that to mean that there is no cause for alarm. So when two confederates look at the smoke and then turn back to their questionnaires, it is not too surprising that only 10% of people bother to go alert the experimenter to the growing haze in the room. Even when the situation includes other naive bystanders like yourself, if you are all glancing at each other trying to decide whether there is anything to be worried about, then no one is actually doing anything. What occurs in this situation is known as pluralistic ignorance. The inaction of all the members of the group can itself contribute to a collective ignorance that anything is wrong. In such situations, when bystanders are instead able and encouraged to communicate with one another, they are not paralyzed by pluralistic ignorance (Darley et al., 1973). So if you’re in a group and think something is wrong but are not sure, communicate with others about it!

Pluralistic ignorance

A situation in which individuals rely on others to identify a norm but falsely interpret others’ beliefs and feelings, resulting in inaction.

Step 3: Take responsibility. In some of our examples, bystanders should sail through these first two steps. When you hear someone tell you outright that they need help after just informing you of her tendency toward seizures, it is a bit hard to imagine that you wouldn’t notice or be aware that she was in trouble. Nevertheless, the presence of others can prevent us from helping. This is because of another powerful effect that groups can have on us, known as diffusion of responsibility. For a victim to receive help, someone needs to decide that it will be his or her responsibility to act. When you are responsible, the moral thing to do is to help. When you are the only witness, the burden clearly rests on your shoulders. But when others are present, it is easy to imagine that someone else should or has already taken action. In fact, even being primed to think about being part of a group can make people feel less personally accountable and less likely to donate money or stay to help out the experimenter (Garcia et al., 2002). If you ever need help and there are multiple witnesses, you can solve the problem of diffusion of responsibility by picking out—

Diffusion of responsibility

A situation in which the presence of others prevents any one person from taking responsibility (e.g., for helping).

Step 4: Decide how to help. In this day and age, many people can help by using their cellphones to call 911 instead of making a video of the emergency as it unfolds. But in some situations, a specific kind of help is needed. If you feel that you lack the expertise, it is particularly easy to imagine that someone else might be better qualified to give help. A student having a seizure might need someone with medical training, so a witness in the presence of others could hope that someone else is more knowledgeable than he or she would be. In the subway collapse study we talked about earlier, the researchers actually had to exclude two trials that they conducted when a nurse was on the train. In those cases, the nurse immediately rushed to help. When people are trained to handle emergency situations, they are more likely to burst the bubble of inaction and rush to the aid of a person in need even as others stand by and watch (Pantin & Carver, 1982).

Step 5: Decide whether to give help. You’ve noticed the event, interpreted it as an emergency, and taken responsibility, and you know what needs to be done. At this point, the only thing that might still prevent you from providing help is a quick calculation of the risks and other costs involved. When people witness a violent attack, they might be afraid to intervene for fear of getting hurt themselves. When someone has collapsed and needs CPR, witnesses might be worried that they could injure the person when performing chest compressions or otherwise make the situation worse and get sued. To counter these concerns, all 50 states and all the Canadian provinces have enacted “Good Samaritan” laws that protect people from liability for any harm they cause when they act in good faith to save another person.

497

Population Density

Think ABOUT

Social psychologists most often concern themselves with the effects of immediate situations on our behavior. But broader social contexts also can influence how we act. Think about where you live. Is it a small rural community, a large urban area, a suburban neighborhood? If you fall and break your leg, are you more likely to get help depending on the city where you take your tumble? We tend to assume that smaller communities are friendlier places and that large cities bring an inevitable sense of anonymity and indifference to others’ needs (Simmel, 1903/2005). But is that the case?

FIGURE 13.3

Where’s the Help?

Do many hands mean people are less likely to lend a hand? Studies of helping suggest that strangers receive more help in smaller cities than in larger ones.

[Data source: Levine et al. (2008)]

In a unique study, Levine and colleagues (2008) traveled to 24 different U.S. cities and staged the following three helping opportunities. In one situation, a research assistant dropped a pen and acted as though he or she did not notice. In a second, he or she appeared to have an injured leg and struggled to pick up a pile of dropped magazines. In a third situation, the assistant approached people and asked if they could provide change for a quarter. The cities they chose varied from small (Chattanooga, Tennessee, population 486,000), medium (Providence, Rhode Island, population 1,623,000), to large (New York, New York, population 18,641,000). Across the cities, the researchers consistently found that they received less help in larger, denser cities (FIGURE 13.3). For example, the correlation between the population density of the city and likelihood of receiving help was –0.55 when the assistant dropped the pen, –0.54 when the assistant needed help picking up magazines, and –0.47 when the assistant was trying to make change for a quarter. Notice that those correlations are negative, meaning that the bigger the city, the less likely people were to help. There is a kernel of truth to the stereotypical image of small-

498

One caveat, however, is that it is always a bit difficult to know what to make of correlations. Do these patterns tell us something about the personalities of the people living in these different parts of the country or about local cultural norms? Are New Yorkers unhelpful contrarians? Or does living in an urban environment like New York work against whatever help-

Milgram (1970) speculated that living in a dense urban area exposes people to greater stimulation, or noise pollution. Living in a city apartment, you get used to the sounds of sirens, crying babies, car alarms, late-

Urban overload hypothesis

The idea that city dwellers avoid being overwhelmed by stimulation by narrowing their attention, making it more likely that they overlook legitimate situations where help is needed.

|

Why Do People Fail to Help? |

|

Although people are capable of empathy and compassion, their current situation powerfully influences their decision whether to help or not. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

The bystander effect The greater the number of witnesses to a situation requiring help, the less likely any one of them will help. |

Helping— Helping behavior results from several steps in sequence: attending to and interpreting the situation as an emergency. taking responsibility for helping. deciding how to help. cost- At any step, some aspect of the situation (e.g., the presence of others) can short- |

Population density In bigger cities, despite a denser population, people tend to be less willing to help strangers. |