13.6 Who Is Most Likely to Help?

The study of human virtue is as old as history itself. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle stated, “We do not act rightly because we have virtue or excellence, but we rather have those because we have acted rightly.” On the other side of the globe, 200 years earlier, Confucius remarked, “The superior man thinks always of virtue; the common man thinks of comfort.” Both of these great thinkers were commenting on the variability among people in our tendency to be virtuous, moral, and prosocial. People have for centuries used these words of wisdom as touchstones for how to become more virtuous and compassionate. Fast forward well over two millennia. What has modern research taught us about the moral heroes who live among us? How do we identify those individuals who stop to help the person in need even though they are running late for a meeting, those who jump into the raging river to save a perfect stranger from drowning, or those who devote their lives to helping people with terminal illness despite how emotionally draining such hospice care can be? A fair amount of research illuminates the qualities of moral individuals.

499

An Altruistic Personality?

On the one hand, some of the social psychological factors that prevent us from helping seem to question the very notion of a moral character. If seminary students rush by a moaning person as they prepare a sermon on the Good Samaritan, what hope do any of the rest of us have in following the advice of Confucius and Aristotle? Other research, however, suggests that we can measure meaningful individual differences in what is known as the altruistic personality. For example, one such measure assesses the frequency with which people engage in helpful acts such as giving someone directions, donating blood, or offering a seat on the bus (Rushton et al., 1981). Others have emphasized more specific characteristics of the altruistic personality, such as the tendency to take another person’s perspective, a tendency to experience empathy, and a tendency to take personal responsibility for the welfare of others (Eisenberg et al., 1989). When it comes to pinpointing traits relevant to prosocial behavior, we do find evidence that the ability to empathize acts like a trait. Teenagers who score higher in empathy when they are 13 still view themselves as prosocially oriented a decade later, when they are young adults (Eisenberg et al., 2002). Even their moms agree: Those teens who later scored highest in prosociality in their early 20s tended to be seen as pretty helpful kids by their moms a decade earlier. Chances are that the college friend of yours most likely to volunteer for the local soup kitchen was out there raising money for a local charity before he even hit puberty.

Altruistic personality

A collection of personality traits, such as empathy, that render some people more helpful than others.

The ancient philosopher Aristotle (shown to the right of his mentor, Plato) stated, “We do not act rightly because we have virtue or excellence, but we rather have those because we have acted rightly.”

[APIC/Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

Furthermore, although strong situational forces can constrain people’s behavior, keeping them from acting in line with their underlying values and traits, personality characteristics shine through when situations are more ambiguous. Remember the “trading places” study we described earlier, in which participants decided whether to switch places with a confederate and receive mild shocks instead of watching the electricity-

Even relatively young children show evidence of helping that is predicted by personality. In one study with grade-

500

Individual Differences in Motivations for Helping

Some research has tackled the question of who is most likely to help by examining the motivations people generally have for helping. For example, people who score high on a measure of trait agreeableness are thought to be motivated by prosocial concerns (Graziano et al., 2007). They are sensitive to the needs of others and motivated to adapt their behavior to meet those needs. Graziano and colleagues (2007) have found that agreeableness is a good predictor of people’s general willingness to help out, but particularly in those contexts in which helping is not necessarily expected. When it comes to helping family or group members, our dispositional agreeableness doesn’t predict whether we help. But it is a useful predictor of who will help a stranger or a member of a social outgroup. The motivation to act prosocially seems to broaden our scope of social connection.

But saying that someone is motivated to act prosocially could itself be understood in different ways. When you see a child share a toy with a classmate who is feeling sad, is he being helpful because this is merely what he has been told to do, or because he knows he might be praised for being such a helpful little boy, or because he truly wants to make his friend feel better? Research inspired by self-

When you see a child share a toy with a classmate who is feeling sad, is he being helpful because this is merely what he has been told to do, or because he knows he might be praised for being such a helpful little boy, or because he truly wants to make his friend feel better? People have both internal and external reasons for being helpful.

[Dave Clark Digital Photo/Shutterstock]

All this talk of intrinsic motivations brings up the idea that those who are helpful are more likely to see themselves as helpful people. In other words, some people stake their sense of identity on being moral (Aquino & Reed II, 2002), a finding that fits research conclusions regarding the Nazi-

Being oriented toward others, and incorporating that role into one’s sense of identity, also bodes well for sustaining prosocial behavior over time. People who are more oriented toward others and better at taking their perspective tend to volunteer more and also are better able to sustain such volunteer activity over longer stretches of time. For example, in one study the best predictor of whether people volunteered for AIDS organizations was the extent to which they were motivated toward others, rather than toward the self (Omoto et al., 2010). Of course, they can’t do or sustain it alone, that is, only on the basis of their own motivation. Levels of social support for the volunteer experience, and the satisfaction they get from the experience itself, also contribute to whether they keep at it (Kiviniemi et al., 2002; Omoto & Snyder, 2002; Penner & Finkelstein, 1998). In fact, when these experiences are positive and rewarding, the role of volunteering is more likely to become incorporated into one’s identity. The more helping is part of one’s identity, the more likely one is to sustain an investment in these kinds of prosocial activities (Piliavin et al., 2002).

501

The Role of Political Values

We’ve seen that morality clearly plays a role in helping, but at least in the United States, different moral domains are important to people, depending on their political orientation. In American political culture, liberals are sometimes seen as “bleeding hearts,” but what is the evidence that people’s political leanings predict a more prosocial orientation? One way to answer this question is to look at how people’s ideologies relate to the kinds of policies they support. True to the “bleeding heart” label, when it comes to providing assistance to people who are poor, sick, homeless, or unemployed, liberals more than conservatives vote in favor of such social programs (Kluegel & Smith, 1986). Whereas conservatives are more likely to withhold public assistance to people whom they view as responsible for their own predicament, liberals tend to support providing assistance to people regardless of how they got there (Skitka & Tetlock, 1992; Skitka et al., 1991; Skitka, 1999; Weiner et al., 2011). But this liberal generosity only extends so far. If resources are scarce and belts need to be tightened, both liberals and conservatives choose to help those who are least to blame for being in a bind.

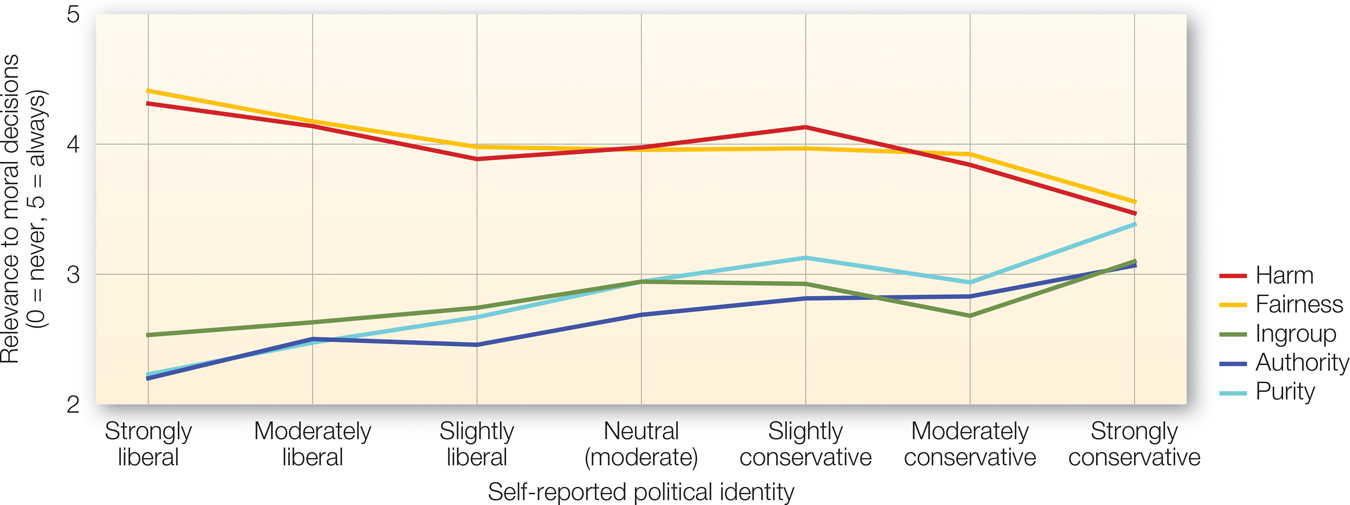

FIGURE 13.4

Political Differences in Moral Foundations

Although Americans generally place the highest value on being fair and doing no harm, conservatives also base their moral decisions on ingroup loyalty, respect for authority, and purity, whereas liberals want to help those who are suffering unnecessarily.

[Data source: Graham et al. (2009)]

What accounts for these differences in political proclivities of helpfulness? Are liberals more empathic and less inclined to make “us versus them” distinctions? Are conservatives simply savvier in making financial investments that pay off for society as a whole? Some evidence points to the different motivations of liberals and conservatives in making policy decisions (Skitka & Tetlock, 1993). Conservatives are more motivated to maintain traditional values and norms. When they see people violating those norms, there are more inclined to punish than to help them. Liberals, on the other hand, are more motivated by egalitarian values and don’t like to see a price tag put to anyone’s pain and suffering.

We can also gain insight into the role of political ideology in moral reasoning by turning to research on moral foundation theory, which we introduced back in chapter 2 (e.g., Graham et al., 2009). This work finds that people take into account five guiding principles when they prioritize whom and when to help or how to be virtuous: preventing harm to others, ensuring fair treatment to all, being loyal to one’s group, respecting authority, and maintaining purity in one’s actions (Haidt & Joseph, 2007).

In FIGURE 13.4, you can see that across the political spectrum, Americans generally make moral decisions with an eye toward avoiding harm and maintaining fairness (Graham et al., 2009). The graph also shows that conservatives prioritize respecting authority, maintaining purity, and protecting the ingroup—

502

The Role of Gender

What are little boys made of?

Snips and snails and puppy dogs tails,

That’s what little boys are made of.

What are little girls made of?

Sugar and spice and everything nice,

That’s what little girls are made of.

—Traditional nursery rhyme

We’ve all heard this nursery rhyme and its chipper little message about sex differences. This cultural clipping reflects an assumption that boys are rough and tumble, girls sweet and good. Although discussions of sex differences and stereotypes often turn on ways in which women are thought to be weaker, more submissive, and less competent than their male peers, prosocial behavior is one arena in which women usually are thought to reign victorious. For example, in 2012, women made up more than 70% of those working in professions such as counseling (70%), social work (81%), teaching (74%), nursing (91%), medical assistance (94%), legal assistance (86%), administrative support (73%), restaurant host-

First, we can ask whether any sex differences in personality traits are associated with a prosocial orientation. Women often score higher than men on measures of agreeableness (Feingold, 1994) and empathy (Baron-

One problem with focusing on gender differences in personality, however, is that personality is most often measured with surveys. This means that what we really learn is whether women think about themselves as being more helpful and prosocial compared with how men think of themselves. We might ask ourselves whether these gender differences in self-

503

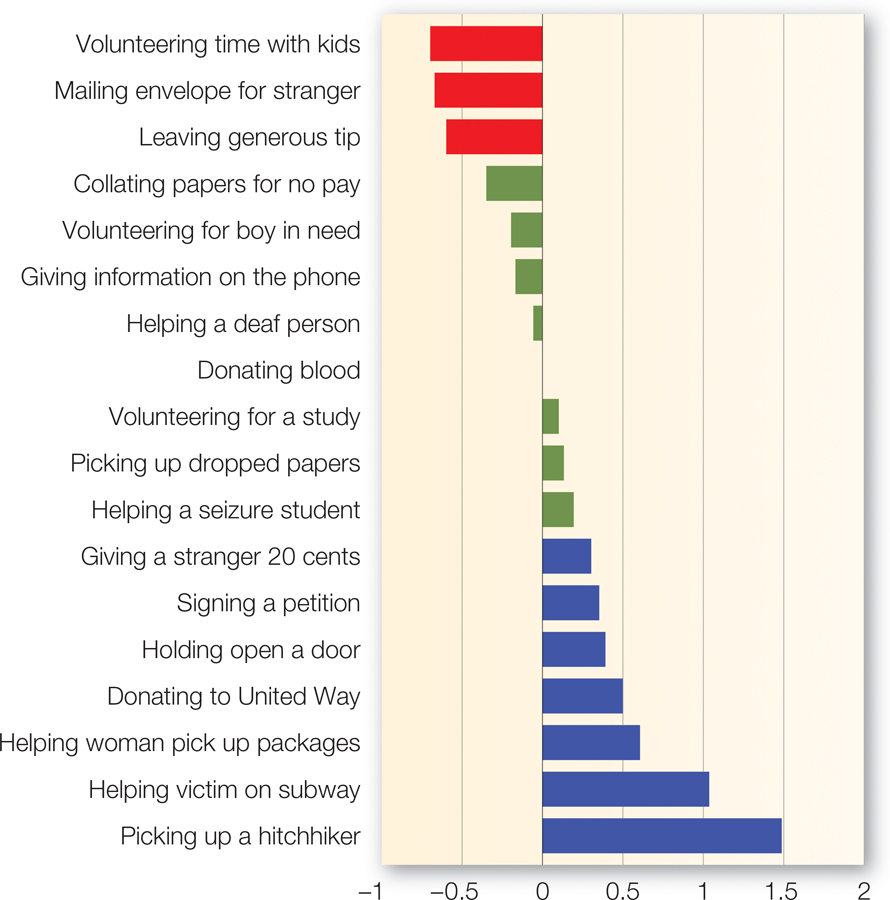

FIGURE 13.5

Gender Differences in How We Help

A review of studies on helping reveals that men and women help in different ways. Women are more likely to volunteer time, sometimes on an ongoing basis, to provide care for others (red bars), whereas men are more likely to help in potentially dangerous situations or when norms for chivalry are present (blue bars).

[Data source: Eagly & Crowley (1986)]

Before we draw broad conclusions about gender and prosocial tendencies on the basis of this result, let’s take a closer look at some of the studies reviewed in the meta-

Eagly and Crowley coded these studies for various characteristics and noted that men are more likely to help in those situations that call for chivalrous behavior or taking action in spite of possible danger. Men are more likely to help a woman with heavy packages, hold a door open (especially for a woman), or be willing to take the risk of picking up a hitchhiker or letting a stranger in to their home. Men are also more likely to help when others will know that they have helped, suggesting that men more than women might act prosocially as a way to boost their own social status. They might be smart to do this: It turns out that women report being more attracted to men who behave prosocially (Jensen-

Women, on the other hand, are more likely to volunteer their time for others or go out of their way to mail a letter that has been left behind. In other words, both men and women are prosocially oriented in some ways, but gender roles suggest who should help in which kinds of situations. Underscoring these conclusions from research, more men than women have received the Carnegie Hero Fund Award (given for heroic acts), whereas more women than men have received the Caring Canadian Award (which rewards volunteerism).

504

If there are some average differences in prosocial orientation between men and women, are these differences really a function of “what little boys and girls are made of,” as the poem would suggest? Or are they passed along from one generation to the next through such poetry? As in most nature versus nurture disputes, both elements likely factor in. On the side of biology, Shelly Taylor and her colleagues have argued that in addition to the typical fight-

Developmental and comparative studies also provide compelling evidence for sex differences. In babies who are less than a year old, boys look longer at a truck than at a doll, whereas girls look longer at a doll than a truck (Alexander et al., 2009; Ruble et al., 2006). Because these same sex-

Other perspectives layer on top of these initial differences the role of socialization and cultural influences in magnifying gendered behavior (Bussey & Bandura, 2004). From Eagly and Crowley’s perspective, because we so often see women in caregiving, communal roles, little girls grow up to be better able to envision themselves in those roles. Those communal personality traits might also be shaped partly by our environment. For example, grade-

Even among the most aggressive nonhuman primates, some evidence indicates that sex differences in more communal or affiliative behaviors can be reduced by cultural changes. For example, baboons are thought to be one of the most aggressive primate species. Like most female primates, female baboons are more affiliative than the males, spending more of their time grooming each other and caring for offspring. The male baboons are much more aggressive and combative, fighting with competing troops and establishing a hierarchy of dominance. In the 1980s, the primatologist Robert Sapolsky observed a troop of baboons in East Africa whose behavior changed entirely when the most dominant males in their hierarchy suddenly died of tuberculosis. Without these alpha males around, the remaining males in the troop began to engage in more affiliative grooming behavior—

Think ABOUT

Think about your own experiences. In what ways do you feel culture has influenced the ways that you help others?

505

|

Who Is Most Likely to Help? |

|

Although situations matter, there are meaningful individual differences in prosocial tendencies. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Altruism Personality traits such as moral reasoning, sense of social responsibility, and empathy predict altruism. |

Individual differences People who identify themselves as being moral and helpful generally are more prosocial. |

Political values Political conservatives and liberals endorse different moral foundations, making them more or less likely to help depending on their moral interpretation of the situation. |

Gender Women are generally seen as being more prosocial, but in some situations men are more willing to help. |

APPLICATION: Toward a More Prosocial Society

|

APPLICATION: |

| Toward a More Prosocial Society |

Our tour through the research on prosocial behavior has taught us that humans, along with many other social species, have an innate capacity for helping. It is important to note, however, that there is also variation in this tendency and the degree to which we act on it. It might not even be realistic to expect individuals to engage in prosocial behavior all the time. As a New York teenager, living in Queens and attending a high school in Manhattan, one of your authors had to take an hour subway ride to school every day. A thought he had numerous times during that commute was that if he had stopped to help every person in need he saw during that morning journey, he never would have made it to school on the average day. People have to take care of their own needs and responsibilities. Fortunately, their efforts to become secure and fully developed adults make it more likely that they will then be better able to contribute to society in small and sometimes big ways throughout their lives. As in the advice given during the safety instructions before a flight, you might have to put on your own oxygen mask before you can properly help someone else put on theirs.

Having acknowledged that, we also can acknowledge that there is undoubtedly room for most if not all of us, in one way or another, to be a little more giving and helpful to each other. This chapter offers a useful blueprint for creating a more prosocially oriented society. In a nutshell, it looks something like this: Raise our children to be adults who have a great capacity for empathy and a strong moral identity. Model how to show warmth and take the perspective of others, especially of those others who seem most different from ourselves. Teach children to view various forms of prosocial behavior as an important basis for being a good, valued person in the world; this can help them become adults who strongly value their identity as generous, helpful people. Parents, teachers, and peers all can enact these changes. Through television shows, movies, and video games, the mass media also can facilitate them by depicting more prosocial role models. It would help further if these media resources reinforced the rewarding nature of prosocial behavior. These changes will be more likely the more we foster a communal orientation in how we think about our families, friends, communities, culture, humanity, and even perhaps all living things.

CONNECT ONLINE:

Check out our videos and additional resources located at: www.macmillanhighered.com/