14.4 Gender Differences in Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors

We’ve seen how men and women sometimes differ in what they find attractive. It turns out they differ in attitudes and behavior regarding sex as well. Most of us are familiar with the common stereotypes: Men, it is often said, want sex all the time, whereas women typically play the role of gatekeeper, deciding if and when sex begins in a relationship. Is there some truth to these stereotypes? Although there is important variation within each gender, many findings support the idea that, compared with women, men have more permissive attitudes about sexuality in and out of relationships:

Men are much more likely than women to say that they would enjoy casual sex outside the context of a committed relationship, whereas women prefer to engage in sexual activities as part of an emotionally intimate relationship (Hendrick et al., 2006; Oliver & Hyde, 1993; Ostovich & Sabini, 2004).

If you ask teenagers how they feel about having sex for the first time, most of the young men cannot wait to lose their virginity, and only one third of them view the prospect with a mix of positive and negative feelings. Young women have a different view: Most are ambivalent about having sex, some are opposed, and only a third of them are looking forward to their first experience of sex (Abma et al., 2004).

If you went on a date with someone and didn’t have sex, would you regret it? Men report regretting not pursuing a sexual opportunity much more often than women do (Roese et al., 2006).

The following scene from the movie Annie Hall (Joffe et al., 1977) satirizes how men and women can view sex differently.

[Alvy and Annie are seeing their therapists at the same time on a split screen]

Alvy Singer’s Therapist: How often do you sleep together?

Annie Hall’s Therapist: Do you have sex often?

Alvy Singer [lamenting]: Hardly ever. Maybe three times a week.

Annie Hall [annoyed]: Constantly. I’d say three times a week.

[United Artists/Photofest]

Once in a romantic relationship, men want to begin having sex sooner than women do, they want sex more often, and they are more likely to express dissatisfaction with the amount of sex they have (Sprecher, 2002).

The differences between men and women go beyond what they say. When we look at what people are actually doing, men on average have higher sex drives than women do:

Men experience sexual desire more frequently and intensely than do women, and they are more motivated to seek out sexual activity (Vohs et al., 2004). Young men experience sexual desire on average 37 times per week, whereas women experience sexual desire only about 9 times per week (Regan & Atkins, 2006). Men also spend more time fantasizing about sex than women do: Sex crosses men’s minds about 60 times per week; for women, only about 15 times (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995; Regan & Atkins, 2006).

Men spend more money on sex. Not only do men spend a lot of money on sexual toys and pornography (Laumann et al., 2004), men are much more likely than women to pay for sex. One study found that, among Australians, 23 percent of men said that they paid for sex at least once, but almost none of the women had (Pitts et al., 2004).

Men masturbate more frequently than women do (Oliver & Hyde, 1993). Among people who have a regular sexual partner, about half of the men still masturbate more than once a week, whereas only 16 percent of women pleasure themselves as frequently (Klusmann, 2002).

Men are more likely to be sexually unfaithful to their romantic partners. Although most husbands and wives never have sex with someone other than their partner after they marry, about one out of every three husbands, compared with only one out of five wives, has an extramarital affair (Tafoya & Spitzberg, 2007).

Where polygamy is practiced, such as in some African cultures, it is almost always men who have the multiple spouses (Zeitzen, 2008).

These and other facts paint a pretty clear picture: On average, men are more sex driven than women, and are interested in more frequent sex with more partners. A big question, of course, is why these differences exist.

539

An Evolutionary Perspective

Evolutionary psychology gives us one way to understand these sex differences. Robert Trivers (1972) proposed that reproductive success means different things to men and women because the sexes differ in their inherent parental investment, that is, the time and effort that they necessarily have to invest in each child they produce. Men’s parental investment can be relatively low. If a man has sex with 100 different women in a year, he can, in theory, father as many as 100 children with little more time and effort than it takes to ejaculate. Women have a much higher level of parental investment. The number of children they can bear and raise in a lifetime is limited, and they have to commit enormous time and energy to each child lest it die before reaching maturity.

Parental investment

The time and effort that parents must invest in each child they produce.

Trivers argued that because men and women differ in the necessity of their parental investment, they evolved to have different mating strategies, or overall approaches to mating, that helped them to reproduce successfully (Buss, 2003; Geary, 2010). For men, there may be some benefit to a mating strategy of pursuing every available sexual opportunity and to focus more on a short-

Mating strategies

Approaches to mating that help people reproduce successfully. People prefer different mating strategies depending on whether they are thinking about a short-

Women, in contrast, would get no reproductive benefit from being highly promiscuous. If they flitted from partner to partner, mating indiscriminately, they would not be able to produce any more children than they would by having sex with only one fertile man for a lifetime. Instead, women would benefit from a mating strategy of choosing their mates carefully, seeking out partners with good genes who would contribute resources to protect and feed their offspring. In other words, women might prefer a long-

This evolutionary perspective could explain many of the systematic gender differences in sexual attitudes and behavior that we listed above. Given the evolutionary explanation, it is not surprising that men all over the world show a greater desire than women for brief affairs with a variety of partners, and that when they enter a new romantic relationship, they are more eager than women to jump in the sack (Schmitt, 2005). What’s more, women are indeed more careful and deliberate than men in their choice of sexual partners. They are less interested than men are in casual, uncommitted sex (Gangestad & Simpson, 1990). They will not have sex with a partner unless he meets a fairly high bar of intelligence, friendliness, prestige, and emotional security, whereas men set the bar much lower for the personal qualities they demand in a potential sexual partner (Kenrick et al., 1990).

It is important to note, however, that the evolutionary perspective does not imply that men and women employ a single mating strategy across all situations and periods in their lives, or, for that matter, that all men and women will employ the same strategy. For one thing, the mating strategies that men and women adopt depend on whether they are looking for a short-

It is also important to emphasize that any strategy has its costs and benefits. The social, cultural, and physical environment can alter the way these balance out (Geary, 2010). Some of these trade-

|

Costs |

Benefits |

|---|---|

| Women’s short- |

|

|

Risk of disease Risk of pregnancy Reduced value as a long- |

Some resources from mate Good genes from mate |

| Women’s long- |

|

|

Restricted sexual opportunity Sexual obligation to mate |

Significant resources from mate Paternal investment |

|

Men’s short- |

|

|

Risk of disease Some resource investment |

Potential to reproduce No parental investment |

|

Men’s long- |

|

|

Restricted sexual opportunity Heavy parental investment Heavy relationship investment |

Increased paternal certainty Higher- Sexual and social companionship |

|

[Research from: Geary (2010)] |

|

540

Thus, even if certain mating strategies were adaptive in our distant evolutionary past, they should not be viewed as natural or preferable ways to act. For example, although mating with as many women as possible brings a man some elements of advantage, it also brings potential costs: conflict with and violent reactions by other men in the man’s vicinity; development of a negative reputation among women in the vicinity; and lack of contribution to the survival of the children he does father. All of these factors would favor a more monogamous approach. In certain contexts, then—

Consider today’s modern world. Do you think these strategies would be advantageous in the contemporary mating landscape? In the modern environment we inhabit now, male promiscuity and female chastity might not necessarily help people reproduce more effectively. For one thing, many women now use birth control to prevent fertility. Also, many casual sexual encounters involve the use of prophylactics to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases (as well as pregnancy). In fact, in this environment, men might be able to reproduce more successfully if, instead of pursuing multiple partners, they consistently showed love and commitment to one partner and increased their parental investment. Geary (2010) notes, for example, that humans are quite different from nearly all other mammals in the relatively high degree of involvement that fathers have in child rearing. Furthermore, as women gain more equal footing with men in terms of economic and social power, and because technology has potentially reduced the burdens of infant care (e.g., formula as a substitute for breast milk, the ability to pump and store breast milk), women may benefit from a less selective approach (Schmitt, 2005). These are just a few of the cultural factors influencing people’s views of sex and their sexual behavior. Next we briefly consider additional factors that play a role in sexual attitudes and behavior.

541

Cultural Influences

It is important to recognize that although sex obviously serves the biological function of reproduction, many psychological motives influence people’s decisions to have sex. When college students were asked to list all of the reasons why they or someone they know had recently engaged in sexual intercourse, they mentioned 237 reasons (Meston & Buss, 2007). Most of these reasons had to do with seeking positive states such as pleasure, affection, love, emotional closeness, adventure, and excitement. Students also mentioned more calculating and callous reasons, albeit less frequently. Some used sex as a way to aggress against someone (“I was mad at my partner, so I had sex with someone else”), to gain some advantage (“I wanted a raise”), or to enhance their social status (“I wanted to impress my friends”).

Lynne Cooper and colleagues (1998) have shown that many of these reasons for sex boil down to five core motives. Specifically, she finds that the among both college-

Whether a person has sex is influenced by the prevailing cultural norms about what is and what is not permissible. Whether you are a man or a woman, you probably are more accepting of premarital sexual intercourse than your grandparents were. Sixty or so years ago, most Americans disapproved of sex before marriage; these days, fewer than a third of Americans think that premarital sex is wrong (Wells & Twenge, 2005; Willetts et al., 2004). At the same time, most people generally disapprove of sex between unmarried partners who are not emotionally committed to each other, and they look more favorably on sexually active partners who are in a “serious” rather than a “casual” relationship (Bettor et al., 1995; Willetts et al., 2004). In short, although people today generally are not expected to “save themselves for marriage” in the same way that your grandparents were expected to do, most of us still believe that sex outside of marriage is more acceptable if it occurs in the context of a committed, affectionate relationship (Sprecher et al., 2006).

These changes in norms over the past few decades are also reflected in people’s sexual behavior. In today’s United States, by the age of 44, almost everyone—

Cultural norms influence not only whether people engage in sex, but how comfortable they feel about reporting permissive sexual attitudes and behavior. Consider this puzzle: The average middle-

542

But another explanation is that men tend to exaggerate the number of partners they’ve been with, whereas women tend to minimize that number (Willetts et al., 2004). When men are asked about their number of partners, they tend to estimate the number rather than counting diligently, and when in doubt, they round up. As a result, they almost always report round numbers, such as 10 or 30, and almost never provide seemingly exact counts such as 14 or 27 (Brown & Sinclair, 1999). Women, on the other hand, respond to researchers’ inquiries into their sex lives by counting their partners more accurately and then fudging by subtracting a partner or two from their reported total (Wiederman, 2004).

How do we know that norms play a role in men’s and women’s biased reporting? You might expect that if, for impression-

More generally, cultures vary in the permissiveness of their attitudes regarding sex, presumably as a result of particular historical, political, and religious influences. Americans have more conservative sexual attitudes than people in many other technologically advanced countries (Widmer et al., 1998). For example, when asked about their attitudes about sex before marriage, sex before age 16, extramarital sex, and same-

|

|

Percentage of Respondents Who Felt This Type of Sex Was Always Wrong |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Countries |

Sex before marriage |

Sex before Age 16 |

Extramarital sex |

Same- |

|

Australia |

13% |

61% |

59% |

55% |

|

Canada |

12 |

55 |

68 |

39 |

|

Germany |

5 |

34 |

55 |

42 |

|

Great Britain |

12 |

67 |

67 |

58 |

|

Israel |

19 |

67 |

73 |

57 |

|

Japan |

19 |

60 |

58 |

65 |

|

Netherlands |

7 |

45 |

63 |

19 |

|

Russia |

13 |

45 |

36 |

57 |

|

Spain |

20 |

59 |

76 |

45 |

|

Sweden |

4 |

32 |

68 |

56 |

|

USA |

29 |

71 |

80 |

70 |

|

[Data source: Widmer et al. (1998)] |

||||

One general point to take from all this is that although some of the reasons people pursue sex certainly involve biological tendencies toward pleasure seeking and reproduction, many others reflect how a person is shaped by, and interacts with, his or her social and cultural environment.

Your Cheating Heart: Reactions to Infidelity

Let’s do a little thought experiment, shall we? Imagine you are in a committed relationship with someone whom you love very deeply. If you are lucky, maybe you already are there, and not much imagination is required. Now imagine that you learn that your partner has been carrying on secretly with another person. In one version of this dark scenario, you learn that the affair is about wild, passionate sex. In an alternative version, it is about a deep emotional attachment. If you were forced to choose between these two tragic turns in your relationship, which would seem to be the lesser of two evils?

Early Research

When researchers first examined how people react to infidelity, they found evidence of a significant difference between men and women. In an early set of studies, 49% of men but only 19% of women said they would be more upset if they caught their partner sleeping around than if their partner had fallen for another person (Buss et al., 1992). Of course, this means that 81% of women, compared with only 51% of men, said they would be more bothered by learning that their partner had fallen in love with someone else. Do men and women really have such different views of disloyalty? If so, why? The next two decades of research sought to answer these two questions.

543

Despite humans’ monogamous tendencies, cases of infidelity in committed couples do occur with some frequency, as previously noted (Tafoya & Spitzberg, 2007). From an evolutionary standpoint, people have a lot to lose from their partner’s extrarelational affairs. The emotion of jealousy might have evolved to be an affective warning light signaling our partner’s real or imagined indiscretions. Jealousy might cue us to be alert to possible rivals who could catch our partner’s eye and woo him or her away (Buss, 2000). But an evolutionary perspective claims that infidelity carries different meanings for men and women because it differentially affected their ability to reproduce.

Of course, marriages do happen and men stay around to change diapers, attend dance recitals, and coach little Susie’s soccer league. These monogamous tendencies are thought to have evolved, and led to cultural rituals that sanction them, because there was an adaptive advantage to having the proud papa available to provide resources, protection, and a role model for developing kids (Geary, 2010). Romantic attachments provide the emotional glue to bond couples together. From this theory of evolved cost-

Mate guarding

The process of preventing others from mating with one’s partner in order to avoid the costs of rearing offspring that do not help to propagate one’s genes.

544

Modern Perspectives

This evolutionary argument for gender differences in jealousy fits the findings of those early studies, but theorists soon raised questions both about the data themselves as well as the conclusions that might be drawn from them. Some research fits the original view. Some does not.

First, following up on Buss’s original research, studies have replicated his pattern of sex differences. Men’s greater worry over sexual infidelity and women’s greater concern with emotional infidelity have been found across cultures (Buss et al., 1999; Buunk et al., 1996; Geary et al., 1995) and also show up when people consider online relationships (Groothof et al., 2009). A meta-

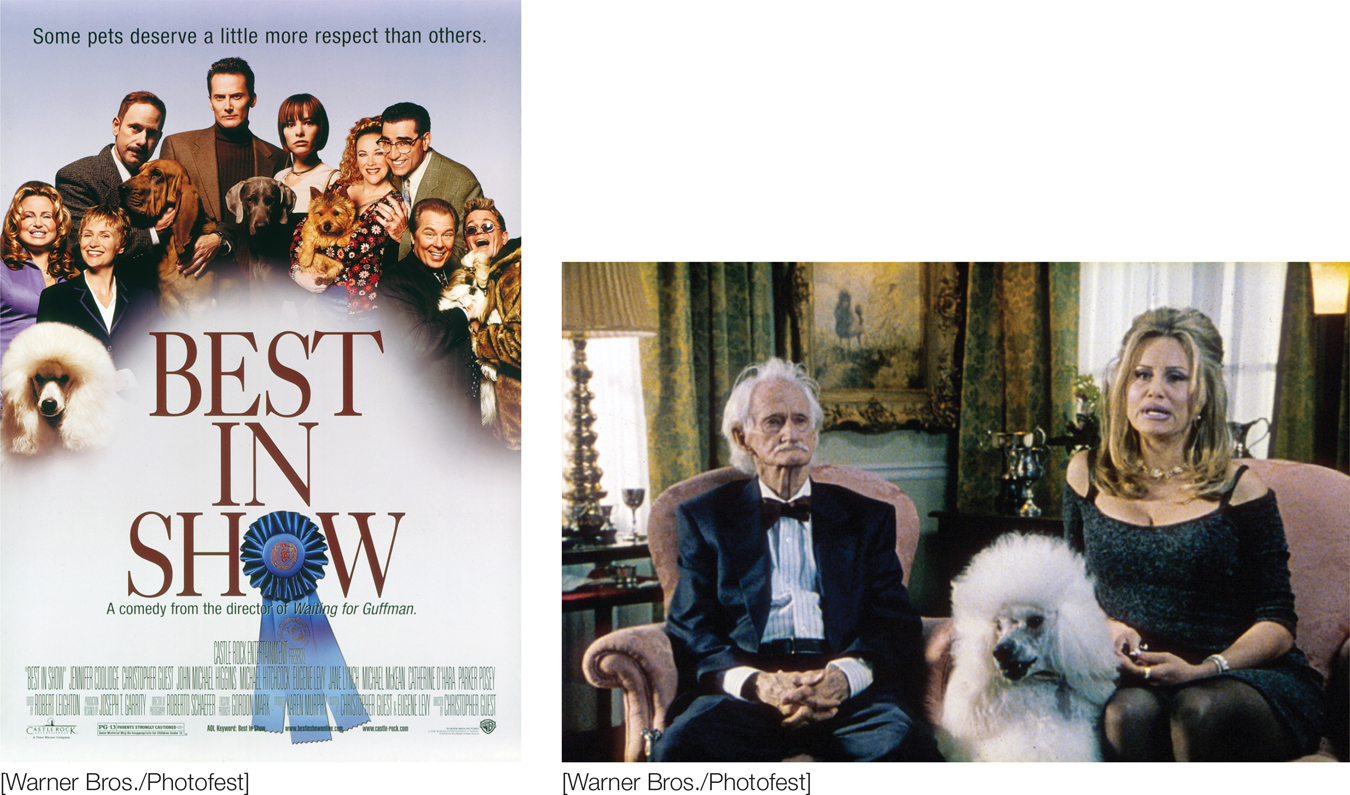

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

Human Attraction in Best in Show

Human Attraction in Best in Show

At first glance, the movie Best in Show (2000) might seem like an odd choice for a discussion of human attraction. What does a mockumentary about a dog show have to do with how people partner up? But on closer inspection, it provides the perfect satirical account of the various factors that attract people to one another. The movie (directed by Christopher Guest) follows the trials and tribulations of several dogs on their journey toward the title Best in Show at the annual Mayflower Kennel Club Dog Show. But the movie really centers around the owners of these dogs and their quirky personalities and relationships.

As the movie begins, we get to know each set of dog owners in an interview-

One couple’s story shows the importance of propinquity. Hamilton and Meg Swan met at Starbucks. Not at the same Starbucks, mind you, but at two different Starbucks that were just across the street from each other. After noticing each other, they soon realized that their shared yuppie interests extended far beyond soy chai lattes to Apple computers and J. Crew. Clearly these two thirtysomethings are meant for each other! Or at least, they have similar attitudes. Unfortunately, as we get to know Hamilton and Meg a bit more, we learn that they also share a tendency to crack under pressure. One gets the sense that this shared disposition for being hot tempered is bound to do this couple in eventually. When their Weimeraner’s favorite squeaky toy goes missing, their frantic search for it leads to an early disqualification from the competition.

Another couple, Leslie and Sherri Ann Cabot, pushes evolutionary theorizing on sex differences in mating strategies to its limits. Leslie is ancient but very wealthy. Sherri Ann is much younger and obviously spends a lot of time on her appearance. But in their interview (during which he merely blankly gums his dentureless mouth), she insists that what really makes their relationship work is his very high sex drive and all the interests they have in common: “We both love soup. We love the outdoors. We love snow peas. And, uh, talking and not talking. We could not talk or talk forever and still find things to not talk about.”

But as the movie continues, it’s clear that their relationship contains no true attraction. Instead, Sherri Ann is having an affair with her dog’s handler, Christy. When Sherri Ann and Christy discuss their relationship to each other and to their poodle, Rhapsody in White, we see that they are attracted by complementary characteristics—

The one couple whose source of attraction to each other is the most difficult to identify is Jerry and Cookie Fleck. Cookie is an energetic and not unattractive middle-

It’s unclear whether Christopher Guest and Eugene Levy, who cowrote the screenplay, intended to convey any broad messages about human attraction. But somehow each of these couples found each other, partnered up, and have remained together through various hardships. One does get the sense, however, that it might be the shared love of dogs and the dog-

545

The story might have ended here, with the field concluding that we have an evolved tendency to feel jealous and that these mental modules of jealousy are distinct for men and women. However, other researchers have had problems with this interpretation and the data on which it has relied. One argument is that the existence of these sex differences actually has been overstated (Harris, 2003). Forcing people to choose between a love affair and a lustful liaison is a rather contrived scenario, a bit like asking whether someone would prefer a kick in the head or a punch in the stomach. Neither is particularly desirable, and by focusing on sex differences in preferring one choice over the other, we might be ignoring a rather obvious but important point: that both sexes would experience jealousy in either case. When people are asked about each kind of infidelity independently rather than being forced to choose between one or the other, the normally observed sex difference seems to disappear (DeSteno & Salovey, 1996; Harris, 2003; Sagarin et al., 2003).

546

Other methodological aspects of the original studies have been questioned. For example, studies of actual infidelity rather than imagined infidelity sometimes replicate the sex difference, but not always (Edlund et al., 2006; Harris, 2002). It also might be difficult to draw conclusions about the greater sympathetic activation when men imagine sexual versus emotional infidelity. It turns out that men generally show greater sympathetic activation when imagining their partner having sex instead of becoming emotionally attached, regardless of whether this imagined relationship is actually with themselves instead of with someone else (Harris, 2000). These critiques of the methods used in the original studies have led some researchers to question how large or meaningful this purported sex difference really is.

If we do accept that men tend to bristle at a wife’s one-

Another culturally based argument is that men derive more self-

A third critique is that certain aspects of the data just don’t seem to fit with an evolutionary account. For example, if differences in jealous reactions truly are sex linked, then gay men should show the same patterns of response found in straight men—

547

Final Thoughts

In sum, the evolutionary account offers a provocative explanation of gender differences in jealousy, but different studies point to other explanations for when and why men and women feel jealous. As scientists continue to examine these processes, we think it is important to get some perspective on these debates. On the one hand, there is general agreement that our current psychology is influenced by our evolutionary past, but that rarely if ever means any particular propensity is rigidly determined by it. If you think about the differences between men and women as a pie, one slice of that pie is our evolved tendencies. Another slice might be cultural upbringing. Yet other slices might be gender differences in other relevant personality traits or the person’s experiences in the immediate social context. The argument about men’s and women’s jealousies might be framed better as what kinds of explanations are the bigger pieces of the pie, not whether the entire pie belongs to evolution or to culture. Maybe the biggest lesson we learn from this line of research is that even scientists get jealous if they worry that a single explanation is getting more than its fair share of attention.

Regarding the sex-

|

Gender Differences in Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors |

|

Men and women differ in behavior and attitudes toward sex. Explaining those differences requires a diversity of perspectives. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

The evolutionary perspective Men’s attitudes reflect the reproductive advantages of mating with multiple women, while women’s attitudes reflect the need to find one mate to help support child rearing. |

Cultural influences Cultural norms also affect attitudes, as evidenced by the change in acceptance of premarital sex across generations as well as among cultures. |

Men, women, and infidelity There is some evidence that men and women view infidelity from different perspectives. Researchers debate the relative role of evolution and culture in creating these differences. |

CONNECT ONLINE:

Check out our videos and additional resources located at: www.macmillanhighered.com/