15.2 This Thing Called Love

To this crib I always took my doll; human beings must love something, and, in the dearth of worthier objects of affection, I contrived to find a pleasure in loving and cherishing a faded graven image, shabby as a miniature scarecrow.

–Charlotte Bronte, Jane Eyre (1847/1992, p. 27)

The British novelist Charlotte Bronte captured a basic truth not only about humans but about other primates as well. Over a hundred years later, the comparative psychologist Harry Harlow discovered that when he separated infant monkeys from their moms and put them in cages by themselves, they became intensely attached to cheesecloth baby blankets he included in their cages; when the blankets were removed for laundering, the poor little monkeys became distressed (Harlow, 1959).

552

In its most general sense, love is a strong, positive feeling we have toward someone or some thing we care deeply about (e.g., Berscheid, 2006). The object of our love is of great value to us. We feel possessive toward it, and if it is a living being, we usually want the love object to love us back. Indeed, in the romantic context, unrequited love causes damage to self-

Romantic Love

Attesting to the importance of romantic love, studies have found that when asked to name the person they felt closest to, the most popular choice was one’s romantic partner (e.g., Berscheid et al., 1989). Many people have made valuable observations about love, including ancient philosophers, poets, and storytellers; Renaissance writers such as Shakespeare; 19th-

I am torn by your love for me

Pain and more pain

Where are you going with my love?

I’m told you will go from here

I am told you will leave me here

My body is numb with grief

Remember what I’ve said, my love

Goodbye, my love, goodbye.

And indeed, when love is unrequited or romantic relationships don’t work out, it can lead to stalking, abuse, murder, and suicide (e.g., Daly & Wilson, 1988; Fisher, 2004).

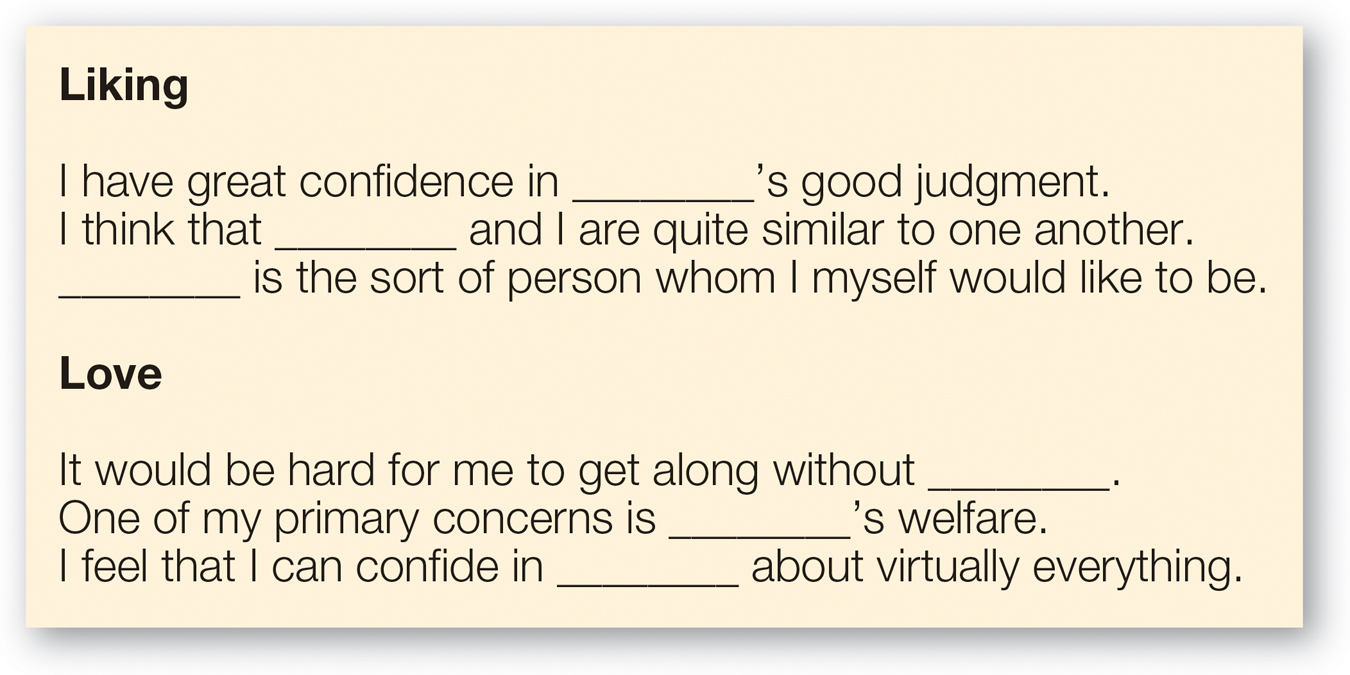

FIGURE 15.1

Sample Items from Rubin’s Liking and Love Scales

Rubin’s liking and love scales were among the first to assess two different kinds of attraction: romantic love and liking.

[Research from: Rubin (1973)]

Social psychologists began focusing on love with Zick Rubin’s seminal 1973 book Liking and Loving. Rubin developed scales to distinguish feelings of liking, which characterize many types of relationships, from feelings of love, which characterize romantic relationships. As the sample questionnaire items in FIGURE 15.1 show, Rubin assessed positive evaluations of, and perceived similarity to, another person as the core of liking, but attachment, caring, and intimacy as the key aspects of romantic love. In support of the validity of his love scale, Rubin found that the higher people scored on love, the more they thought marriage to their partner was likely, the more eye contact they made when with their romantic partner, and the more the relationship had progressed in intensity six months later (Rubin, 1973). Since the development of Rubin’s scale, researchers have developed a variety of other love scales, often tapping particular types or aspects of romantic love (e.g., Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986; Hendrick & Hendrick, 1986).

553

The culture theorist Kenneth Pope (1980, p. 4) described the subjective experience of romantic love this way, consistent with Rubin’s scale:

A preoccupation with another person. A deeply felt desire to be with the loved one. A feeling of incompleteness without him or her. Thinking of the loved one often, whether together or apart. Separation frequently provokes feelings of genuine despair or else tantalizing anticipation of reuniting. Reunion is seen as bringing feelings of euphoric ecstasy or peace and fulfillment.

This description captures what researchers have found out about people who are in the throes of love. After conducting a survey of people’s thoughts about romantic love that she administered in the United States and Japan, the anthropologist Helen Fisher (2004) noted some recurring themes:

The beloved is idealized and becomes a center of attention, intrusive thoughts, emotion, energy, sexual desire, and a special source of meaning and value. The feeling is associated with mood swings from ecstasy to despair, and proneness to feelings of jealousy.

Consistent with the energy, desire, and ecstasy that accompanies love, when people in love contemplate their beloved, there is increased activation of the dopamine-

Of course, love may not be experienced in this way (or at all) by all people or in all cultures. Some people and cultures may see this kind of love as too dramatic or reflecting codependency, but evidence suggests both that when one falls in love and when one is in a love relationship for a decade or more, emotional dependence is pretty likely. This is why people sometimes resort to violence when they perceive a threat to their relationship, or if it is ended (e.g., Fisher, 2004), and why people mourn, often to the point of depressive symptoms, when they lose a romantic partner (e.g., Bowlby, 1980).

We can consider such a high level of emotional investment healthy or unhealthy, but evidence suggests it occurs in many, if not the majority of, committed romantic relationships. From this perspective, love is a leap, a risk, with the individual investing his or her happiness partly on the partner and the relationship. If you love someone—

Culture and Love

Romantic love is partly a cultural creation. The culture we are raised in tells us what love is like, whom we should love and when, and what we should do about love (e.g., Hatfield & Rapson, 1996; Landis & O’Shea, 2000; Rubin, 1973). To gain insight into how the nature of love is articulated, researchers examined the use of words and songs to express love in the United States and China. Although they found similar levels of passion expressed, the Chinese were more likely to incorporate suffering and sadness as part of the love experience (Rothbaum & Tsang, 1998; Shaver et al., 1992). Regarding what to do about love, many contemporary cultures, such as the United States and Japan, consider love a primary basis for deciding whom to marry. But in some cultures, such as those prevalent in many parts of India and Pakistan, marriages are arranged; in fact, basing a marriage on love is considered inappropriate and foolhardy (Levine et al., 1995). Even in European cultures, until well into the 19th century, love generally was not considered a basis for marriage (e.g., Coontz, 2005; Finkel et al., 2014). Rather, marriage was a pragmatic arrangement that served social and economic goals of the bride’s and groom’s families. Rubin (1973) noted that many Western ideas about romantic love developed out of medieval concepts of courtly love. This kind of love was considered likely only between people who weren’t married, often between a man and a woman who became his mistress.

This painting by Eduard Ille, based on a medieval poem called “Underneath the Linden Tree,” is one of many depicting conceptions of romantic love during the Middle Ages.

[Alfredo Dagli Orti/Art Resource, NY]

554

In many stories, such as Romeo and Juliet, love emerges in opposition to cultural forces that control who marries whom. The very well-

Research shows that although specific conceptions of love vary somewhat from culture to culture, love seems to exist in the vast majority of cultures, and perhaps all of them. In a survey of cultures around the globe, anthropologists found clear evidence of romantic love in 147 out of 166 cultures (Jankowiak & Fischer, 1992). What about the 19 cultures without evidence of romantic love? In these cultures, this aspect of people’s lives was not necessarily absent but had not been studied (Fisher, 2006).

Theories of Romantic Love

We’ve seen that culture shapes some features of romantic love, but what explains the widespread existence of the phenomenon and the power it often holds over people? Let’s consider three broad theoretical perspectives that help clarify the nature and importance of romantic love and relationships.

Attachment Theory: Love’s Foundation

From an evolutionary perspective, love may be advantageous because it generally helps us focus on courting and mating with a single individual at a time. This focus conserves energy and motivates lengthy pair bonding, which aids a couple’s effective raising of their offspring (e.g., Fisher, 2004). However, evolutionary adaptations don’t spring out of nowhere; they build on preexisting tendencies and structures. Any compelling theory of love must combine insights from human evolution, human development, and adult psychological functioning. Attachment theory provides just such an integrative perspective on love.

The Basics of Attachment: Infancy and Childhood

Attachment theory is rooted in the ideas of psychologists such as Otto Rank, Karen Horney, and Melanie Klein, but was formally developed by the British psychoanalyst John Bowlby in his three-

555

Infants lack the physical and cognitive abilities to survive in the world on their own. But they have a number of characteristics that we adults seem to find irresistible. These characteristics help to ensure that grown-

[Anneka/Shutterstock]

The importance of this bond is rooted in our primate heritage. But it is particularly essential for humans, whose newborns are the most helpless and dependent of all mammalian species and need the longest period of care before reaching adulthood. Human newborns lack the capacity to roll over, let alone move on their own, find food, feed themselves, or defend themselves against predators. How do they survive long enough to reach some degree of independence? They rely on close attachments to parental figures who can provide care and protection. In fact, infants come into the world with a number of evolved techniques for assuring proximity to attachment figures. For one, their cries guarantee that no one (their parents or anyone else!) can ignore them in times of need. Add those heart-

When infants feel close to an available and responsive attachment figure, they feel comfort and reassurance. Bowlby proposed that when parents are responsive and supportive, they provide a safe haven when the child is fearful and a secure base from which the child can venture forth, explore, and grow.

The developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth studied attachment before and independent of Bowlby. However, after working with Bowlby, she became the primary researcher to study infant attachment systematically. Along with naturalistic observation of infants and their mothers in their homes, she developed a set of strange situation tests to examine the early attachment bond between mothers and their children (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970). Through this research, Ainsworth and colleagues were able to demonstrate the role of attachment in providing young children with psychological security. They were also able to establish three major forms of attachment that are associated with particular patterns of child-

Secure attachment style. In the initial version of the strange situation test, a mother and her nearly one-

The other 40% of the children were split about evenly between two insecure attachment styles.

Anxious-

556

Avoidant attachment style. Children who exhibit the avoidant attachment style are not very affectionate with the mom there. They play with the toys but not very enthusiastically. When the mother leaves, they show little distress, and when she returns, they often turn away or avoid her. Parents of avoidant children tend to reject or deflect the child’s bids for comfort and closeness.

Subsequent research has confirmed this general distribution of what now are known as attachment styles. For example, Campos and colleagues (1983) found that among American samples, 62% of infants were secure, 23% were avoidant, and 15% were anxious-

The Enduring Influence of Attachment: Adult Romantic Relationships

So what does attachment have to do with adult romantic relationships? The nature of this initial love relationship influences the close relationships individuals have over the course of their lives, including adult love relationships. Just as attachment to the parents is central to a child’s psychological security, attachment to the romantic partner is central to psychological security for most adults (e.g., Mikulincer, 2006; Simpson et al., 1992). Attachment theorists explain that these childhood experiences result in working models of relationships—that is, global feelings about the nature and worth of close relationships and other people’s trustworthiness and ability to provide warmth and security (Baldwin et al., 1996; Collins & Read, 1994; Pietromonaco & Barrett, 2000). These working models of relationships, which originate early in life, become our style of attachment, stable patterns in the way we think about and behave in our adult relationships (Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Shaver & Hazan, 1993).

Working models of relationships

Global feelings about the nature and worth of close relationships and other people’s trustworthiness.

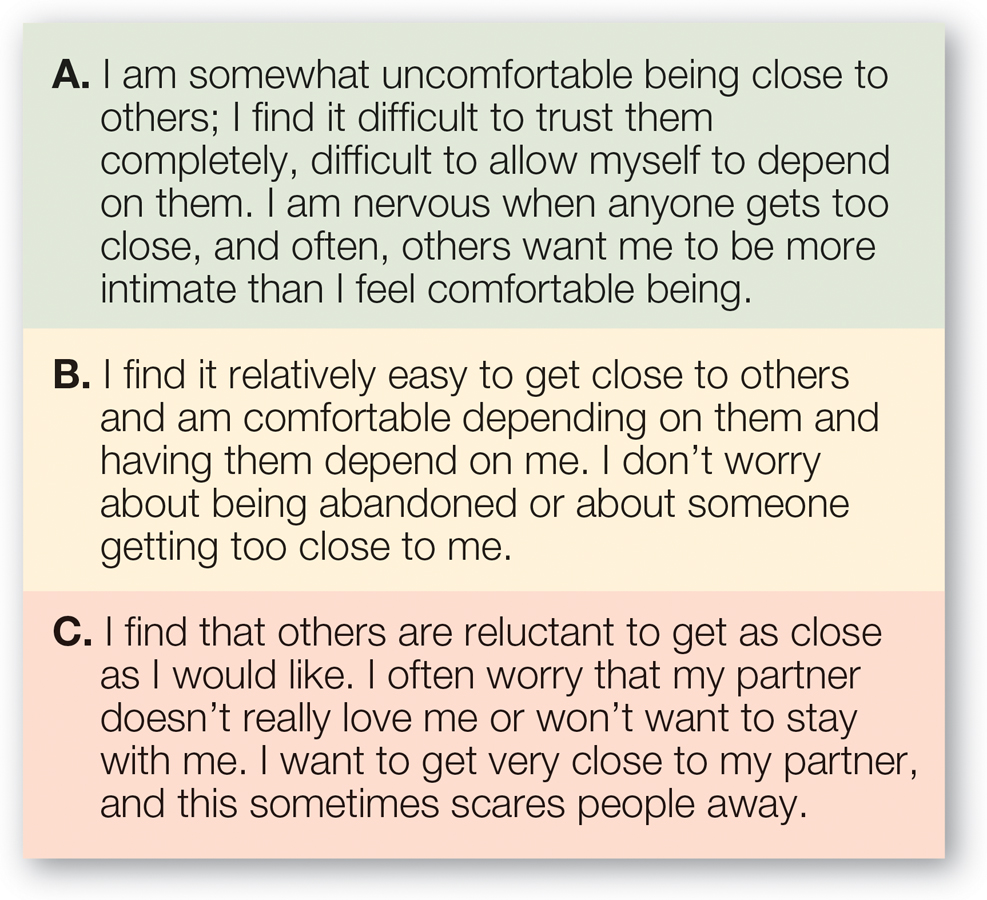

FIGURE 15.2

Attachment Style Questionnaire

Hazan and Shaver developed these descriptions to capture three basic attachment styles. Which one best fits your view of close relationships?

[Research from: Hazan & Shaver (1987)]

Cindy Hazan and Phil Shaver (1987) conducted the first studies providing evidence that these attachment styles relate to adult romantic relationships. They recruited community participants of various ages in their first study and college students in their second study. They created three descriptions of how people think and feel about getting close to others that corresponded to the secure, anxious-

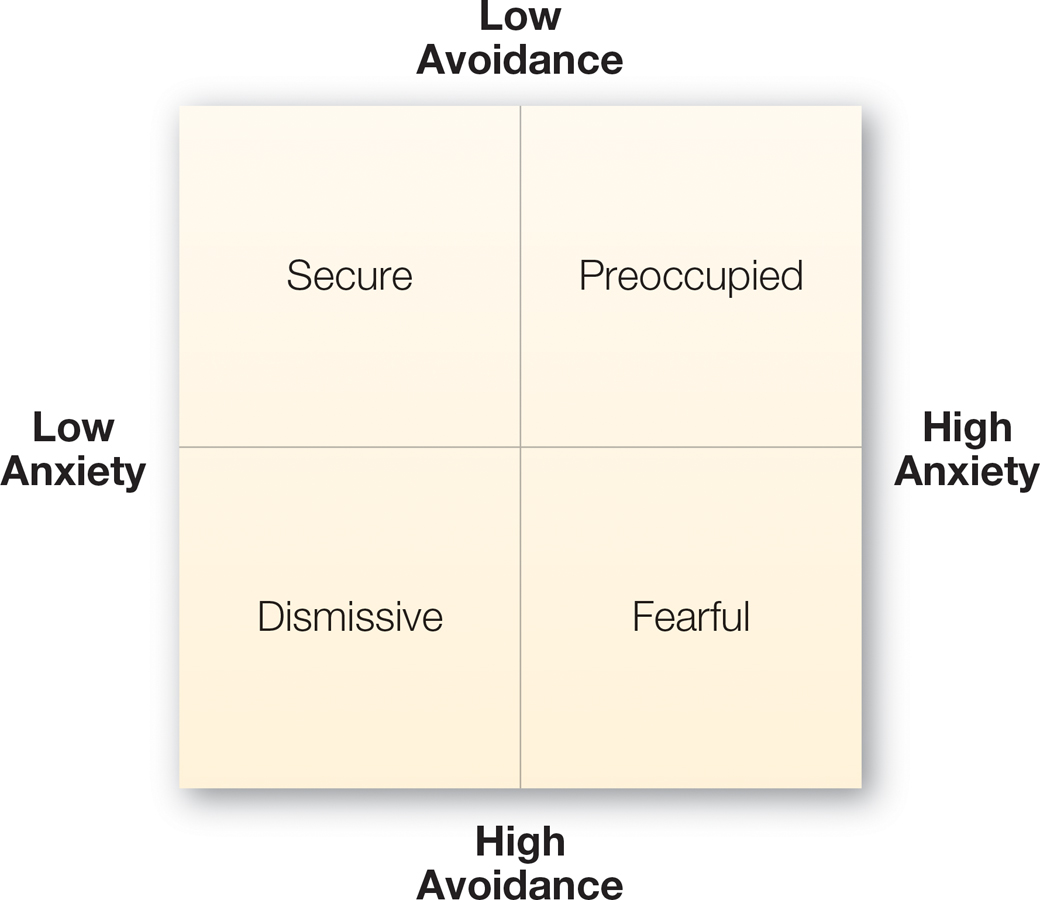

FIGURE 15.3

Attachment Dimensions

Expanding on the categorical approach of distinct attachment styles, research uncovered two attachment dimensions. People can be high or low on attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety, which when crossed yield four attachment styles.

[Research from: Brennan et al. (1998)]

Over the years researchers have specified two dimensions of attachment feelings that underlie these styles of attachment (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Brennan et al., 1998). One dimension is referred to as attachment-

557

Low Avoidance/Low Anxiety: Securely Attached Adults

Participants who are securely attached are low in both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance. They tend to report the longest-

Securely attached

An attachment style characterized by a positive view of the self and others, low anxiety and avoidance, and satisfying, stable relationships.

Those with a more secure attachment style are also more comfortable with their sexuality and generally enjoy sex (Tracy et al., 2003). But this does not mean they will jump into the sack with anybody and at any opportunity. They are also more likely to have sex within a committed relationship (Feeney et al., 1993) and to see sex as a way to enhance intimacy in the relationship and express their love for their partners (Cooper et al., 2006).

Low Avoidance/High Anxiety: Anxious-ambivalent Adults

Anxious-

Anxious-ambivalent

An attachment style characterized by a negative view of the self but a positive view of others, high anxiety, low avoidance, and intense but unstable relationships.

Not surprisingly, they also use and see sex differently. Like many aspects of relationships for these individuals, sex can become riddled with anxiety. The more attachment anxiety men have, the older they are when they first have sex, and they have less frequent intercourse and fewer partners (Feeney et al., 1993; Gentzler & Kerns, 2004). But among anxious-

High Avoidance/High or Low Anxiety: Avoidantly Attached Adults

Participants who report higher levels of avoidance tend to have shorter relationships that lack intimacy (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). They don’t believe love endures, are fearful of closeness, and lack trust in romantic partners. They seem not to want to get much from their romantic relationships, are emotionally distant, and tend to ignore their partners’ needs for care and intimacy (e.g., Collins & Feeney, 2000). They recall their mothers as being cold and rejecting.

People who are high in attachment avoidance show yet another profile of sexual behavior. They are more likely to delay having sex, and when they do, they do so in contexts that limit intimacy, such as having more casual as well as solitary sex (Cooper et al., 1998). This is partly because avoidant people tend to use sex to affirm their desirability and to cope with negative emotions, rather than to seek pleasure or enhance intimacy.

Avoidant styles can come in one of two forms (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1990). High levels of avoidance can be paired with high levels of anxiety (i.e., a fearful avoidant style) and reflect negative views of both self and of others. So the fearfully avoidant person doesn’t feel worthy, doesn’t trust others, and fears rejection. High levels of avoidance can also be paired with low levels of anxiety. Those with this dismissive avoidant attachment style tend to show a positive view of the self but a negative view of others. Dismissive avoidant people are more self-

Fearfully avoidant

An avoidant attachment style characterized by a negative view of both self and others, high anxiety and avoidance, and distant relationships, in which the person doesn’t feel worthy, doesn’t trust others, and fears rejection.

Dismissive avoidant

An avoidant attachment style characterized by a negative view of others but a positive view of the self, high anxiety and avoidance, and distant relationships.

558

Combinations of Attachment Styles and Long-term Relationships

Clearly the best bet for a stable and satisfying long-

Attachment Style, Genes, and Parental Caregiving

Research on attachment theory raises a number of questions. One issue concerns the extent to which a child’s temperament and genetic inheritance contribute to the attachment style he or she develops (Kagan, 1994). Research findings on this issue are mixed. Some studies have found that genes have a negligible influence (e.g., Bokhorst et al., 2003). Other research suggests that DNA associated with low dopamine levels is linked to high levels of attachment anxiety, and DNA associated with low serotonin levels is linked to high levels of attachment avoidance (Gillath et al., 2008). This latter work suggests that about 20% of variability in attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance may result from genetic factors.

Clearly, though, as attachment theory proposes, the primary determinant of attachment style is how attachment figures interact with the child (e.g., Fraley, 2002; Main, 1995; Waller & Shaver, 1994). In one particularly ambitious study, Dymphna van den Boom (1994) showed that when a random half of mothers of temperamentally difficult 6-

Stability of Attachment Style

Another issue concerns stability of attachment style over time. Although the Hazan and Shaver study suggested that early childhood attachment style relates to adult attachment style, the best way to test this stability is with a longitudinal study in which parent-

However, early attachment style is not set in stone. As Bowlby (1980) proposed, experiences with attachment figures throughout one’s life can alter one’s predominant working model of attachment. A horrible relationship, full of betrayal, could make a securely attached person insecure; a happy, stable relationship might shift an insecure person toward a secure style. Indeed, in a four-

559

Love, the Ultimate Security Blanket

As we wrap up our discussion of attachment theory and research, we want to close by reiterating this theory’s central insight regarding love. From the perspective of attachment theory, we seek and maintain love for significant others to garner a sense of support, comfort, relief, trust, and security, particularly when we are confronted with threats from the outside world or distressing thoughts and emotions (e.g., Mikulincer et al., 2001). The sense of warmth and physical protection that we experience as infants when we are close to a responsive caregiver lays the foundation for the comforting experience we have as adults when we feel a secure bond with our romantic partners.

Love and Death

Unable are the Loved to die

For Love is Immortality

–Emily Dickinson (1864/1960, p. 394)

In the weeks following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Americans showed an increased tendency to solidify their close relationships, express more commitment, spend more time with family and friends, and seek more intimate sexual encounters with their romantic partners (e.g., Ai et al., 2009). Various newspapers and magazines such as Newsweek also reported similar trends in the wake of the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 and Hurricane Katrina in 2005, as well as among military units facing more combat and higher levels of violence (e.g., Mitchell, 2009). Why?

One answer comes from the existential perspective offered by terror management theory. Terror management theory is highly compatible with attachment theory in its focus on how children develop security and how that sets the stage for adults’ bases of psychological security. From this theoretical perspective, romantic partners help each other manage the threat of mortality by giving life meaning and reinforcing self-

According to Otto Rank (1936a), as Western societies became more secular during the 20th century, romantic relationships largely replaced religion as the primary source of meaning and value, which in turn provide a sense of transcendence of death. Rank suggested that as this occurred in Western cultures, the romantic relationship became viewed increasingly as a magical, eternal bond of love with a cosmically designated soul mate. Thus, romantic relationships became a central basis of feeling that one’s life is meaningful and enduringly significant. You know you are valued because you are loved. A life partner knows your life story and cares about the minute details of your life, thus bearing witness to and validating your existence and its value. Though perhaps particularly prevalent in modern Western societies, this idea has been around for many centuries and has been expressed in many cultures. A Hindu song put it this way: “My lover is like God: if he accepts me my existence is utilized” (Becker, 1973, p. 161). Eli Finkel and colleagues (2014) have recently made similar observations, suggesting that people in North America increasingly view romantic relationships as a way to meet the needs for self-

560

Studies have supported the idea that romantic partners enhance people’s self-

Further support for the role of romantic relationships in terror management has been provided by a series of studies conducted in Israel by Mario Mikulincer and colleagues, who noted that such relationships may be especially important for managing fear of death because they provide the same type of physical and emotional closeness we all relied on as children when scared (see Mikulincer et al., 2003). They have found that for people in committed relationships, threats to the relationship or thoughts of being away from their partners increase the accessibility of death-

Terror management theory also contributes to understanding the desire for and love of one’s children, as children can be one way to feel that a part of the self lives on beyond one’s own death. In line with this account, research shows that death reminders increase desire for offspring among Dutch, German, and Chinese individuals (Fritsche et al., 2007; Wisman & Goldenberg, 2005; Zhou et al., 2008). Furthermore, for young married adults without children, death reminders increase positive thoughts of parenthood, and thinking about becoming parents reduces the accessibility of death-

The Self-expansion Model: Love as a Basis of Growth

So far we’ve been focusing on theories that portray love primarily as a basis for feeling safe and secure in the world. But this is undoubtedly an incomplete picture of why we pursue love relationships. You’ll remember from chapter 6 that humanistic psychology and self-

According to Art Aron’s self-

Self-expansion model of relationships

The idea that romantic relationships serve the desire to expand the self and grow.

561

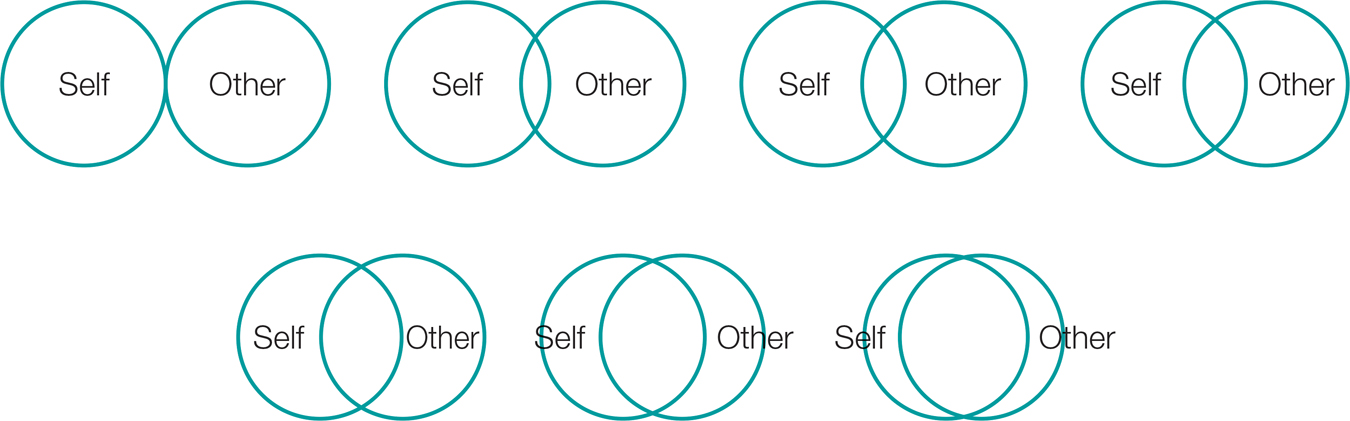

FIGURE 15.4

The Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale

How much mutuality do people feel in a relationship? Asking people to choose the pair of overlapping circles that best portrays their relationship with their partner provides a measure of the closeness they feel.

[Research from: Aron et al. (1992)]

To assess the idea that people incorporate their partners partly into the self, Aron and colleagues (1992) developed the Inclusion of Other in the Self (IOS) Scale. As depicted in FIGURE 15.4, the scale consists of seven pairs of circles that represent varying degrees of overlap between self and partner. Individuals are asked to select the pair that best describes their relationship with their partners. This simple, one-

People who chose more overlapping circles have more satisfying relationships and use more plural pronouns in describing their relationship. They are also more likely to blur the line between their sense of who they are and who their partner is. After rating some traits for self and other traits for their partners, they were more likely to mistake traits they rated for self for those they rated for others (Aron & Fraley, 1999).

The self-

Models of the Nature of Love

Attachment theory, terror management theory, and the self-

Schachter’s Two Factor Theory: Love as an Emotion

Love is often a lasting feeling toward another person, but people also have intense feelings of falling in love and being in love. Where do these feelings come from? Berscheid and Walster (1974) applied Schachter’s (1964) two factor theory of emotion to understanding love as a felt emotion. As you’ll recall from chapter 5, Schachter’s theory proposed that emotions partly consist of physiological arousal and a label for that arousal based on cues present when the arousal is being felt. As applied to love (and lust), this theory suggests that when an individual is aroused, in the presence of a member of the appropriate sex, and in a context that cultural learning suggests is romantic, the individual may very well label that arousal as love. One interesting implication of the two factor theory is that cultures direct when and with whom the label love is most likely to be applied to arousal that occurs in the presence of another person.

562

Don’t look down! But if you do, do you think the emotions you experience might influence your affection for an attractive person you meet on the bridge? When Dutton and Aron (1974) interviewed people on this bridge over the Capilano River in British Columbia, they found that the answer is yes.

[Bob Stelko/Getty Images]

A second interesting implication of this approach is that the real source of the arousal doesn’t always matter, as long as it is labeled attraction or love. One set of studies supporting this idea was conducted by Dutton and Aron (1974). In one of their studies, adult males were interviewed on one of two bridges over the Capilano River in British Columbia by an attractive female interviewer or a male interviewer. One bridge was a very wide, safe bridge, only 10 feet over a small rivulet. The other bridge was a wobbly, narrow 450-

Dutton and Aron used two clever dependent variables to test this idea. First, while on the bridge, the interviewer showed the interviewees an ambiguous picture of a young woman covering her face with one hand and reaching out with the other and asked them to write a brief story about it. Dutton and Aron had the stories coded for sexual content. They expected more sexual content in the stories by the men who were interviewed by the female over the scary bridge. Second, they had the interviewer give the interviewees her phone number in case they wanted to learn more about the study. Dutton and Aron figured that if the scary bridge interviewees were more attracted to the female interviewer, they would be more likely to call her. Both hypotheses were supported. The scary bridge interviewees made more calls and wrote more sexual stories. For example, 50% of these interviewees called, whereas only about 20% called in the other three conditions (male interviewer, safe bridge).

The idea that love and attraction can be fueled by extraneous sources of arousal has been supported in other ways as well (e.g., Valins, 1966; White et al., 1981; White & Kight, 1984). For example, working with the excitation transfer paradigm developed by Zillmann (1971) and described in chapter 5, White and colleagues (1981) showed that arousal from both exercise and funny or disturbing audiotapes subsequently increased male romantic attraction to a physically attractive female confederate. In a study conducted at an amusement park, individuals found a photographed member of the opposite sex more desirable as a date after exiting a roller coaster than before getting on the roller coaster—

How much of our attraction to, and even love for, a romantic partner may have been fueled or intensified by extrapersonal sources of arousal? It is hard to say in any specific case. But the research supporting the two factor theory suggests that initial attraction to or feelings of love for a romantic partner may indeed be affected by extrapersonal sources of arousal. And if you think of what people do when they date others they are interested in, they often do exciting, physiologically arousing things: They go dancing, watch exciting or scary movies, go on amusement-

563

Sternberg’s Triangular Model of Love

There are a variety of models that describe different types of romantic love. Perhaps the most basic distinction is between passionate love and companionate love (e.g., Hatfield, 1988). Passionate love involves an emotionally intense and erotic desire to be absorbed in another person. Companionate love is believed to better characterize older couples who have been together a long time. There is still great affection, trust, and a sense that the relationship is important, but passion is much diminished or absent.

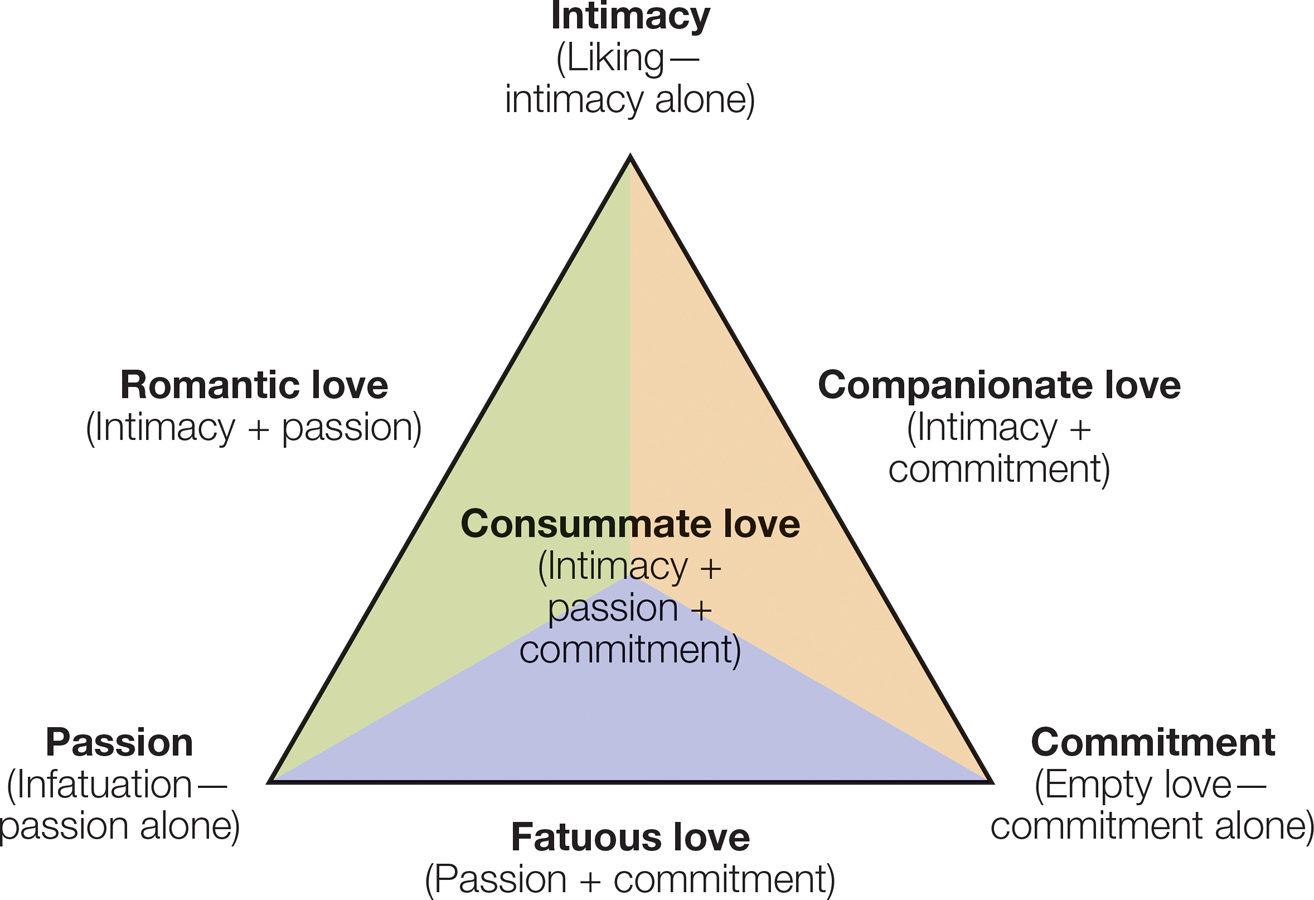

FIGURE 15.5

Triangular Model of Love Relationship

Robert Sternberg proposes that we can break love down into three main facets, which when combined with one another yield seven different types of love. Think about where some of the most important close relationships in your life fit within this triangle.

[Research from: Sternberg (1997) © 1997 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Reprinted by permission.]

Robert Sternberg’s triangular model of love relationships (depicted in FIGURE 15.5) rather elegantly captures not only these two kinds of love but five others as well. The model posits three basic components of love relationships that in different combinations describe different kinds of relationships. The components are passion, intimacy, and commitment. Passion is the excitement about, sexual attraction to, and longing for the partner. Intimacy involves liking, sharing, knowing, and emotional support of the partner. Commitment is the extent to which the individual is invested in maintaining the relationship. Sternberg proposes that the ideal romantic relationship has a high level of all three components. He refers to this as consummate love. Research supports his model by showing that almost all aspects of relationships seem to fit under one of the three factors (Aron & Westbay, 1996) and that people view the ideal lover as someone high in all three factors (Sternberg, 1997).

Many other kinds of relationships lack one or more component, but can still be meaningfully experienced as love. A relationship with only passion is an infatuation; there is strong attraction and arousal, but the partner is not well known and there is no commitment to a relationship. Intimacy alone can characterize a close acquaintanceship or friendship. Commitment alone is labeled by Sternberg as empty love. There is investment in maintaining the relationship, but there is no sharing and no passion. This sometimes occurs in older couples for whom the passion and even the sense of liking for the partner is no longer there, but out of habit, familiarity, or fear of being alone, commitment persists. The relationship still helps the individual feel secure, but there is no growth or stimulation.

The combination of passion and intimacy is labeled romantic, or passionate, love. People are in love and share knowledge of each other but haven’t made a real commitment to sustaining the relationship over time. Romantic love often is a step toward consummate love, but in some cases that commitment is never made. The combination of passion and commitment is called fatuous love and is exemplified by young adults who have developed a strong infatuation and jump to the commitment of marriage before they really know each other well. These kinds of relationships often don’t turn out well because, lacking intimacy, partners don’t know what they are getting into. Each partner will tend to idealize the other, but over time they may encounter less-

Finally, the combination of intimacy and commitment without passion is compan-

564

|

This Thing Called Love |

|

Social scientists have focused research primarily on romantic love. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Romantic love Early research distinguished between liking and loving. Loving typically involves intense caring, intimacy, and a deep emotional investment. |

Culture and love The experience of romantic love is partly shaped by culture. But it is a basic, likely universal aspect of human experience. |

Theories of why love exists Attachment theory proposes that most people seek security from their romantic relationships much as they once did from their parents. The nature of that original child- Terror management theory suggests that love and close relationships help us to buffer the dread of being aware of our mortality. The self- |

Models define the experience of love The two factor theory posits that love is partly a label we apply to feelings of arousal on the basis of contextual cues. The triangular model of love suggests that love is based on combinations of three basic components: passion, intimacy, and commitment. |