15.4 Cultural and Historical Perspectives on Relationships

Think ABOUT

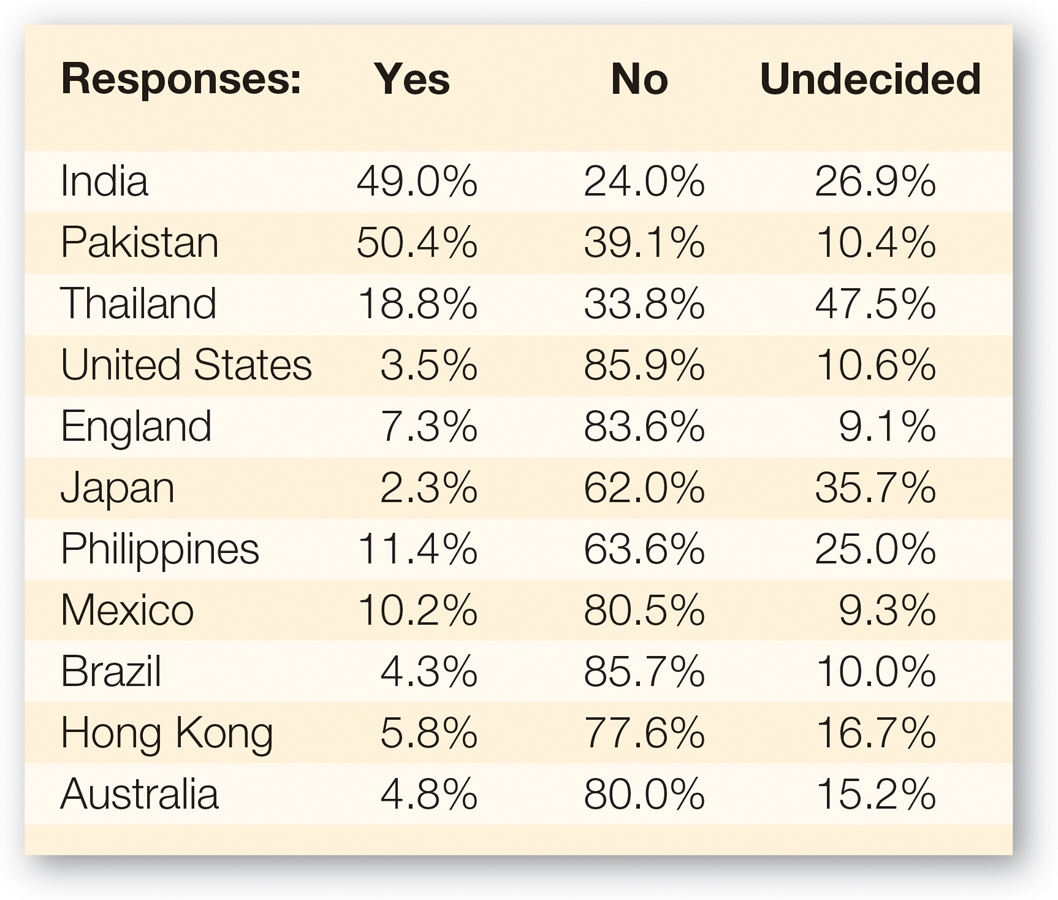

Suppose that a man (woman) had all the qualities you desired in a partner. Think about it. Would you marry this person if you were not in love with him (her)? Chances are that you answered “no.” In today’s Western world, love typically is viewed as the raison d’être for getting hitched and for staying committed to the relationship. We’re bombarded with stories and songs that exalt love as the glue that binds people together and lead us into the happily ever after (Jackson et al., 2006). It is part of our cultural fabric. In fact, when American students were asked this question in 1995, only 3.5% of men and women said “yes” to the prospect of a loveless but otherwise satisfying marriage (Levine et al., 1995). But it’s not just Americans who are romantics. As FIGURE 15.6 shows, respondents from only two of 11 countries were fine with choosing to marry without love—

FIGURE 15.6

Love and Marriage in Different Countries

Responses to the question, If a man (woman) had all the other qualities you desired, would you marry this person if you were not in love with him (her)?

[Data source: Levine et al. (1995) © 1995 SAGE. Reprinted by permission.]

Cross-cultural Differences in Romantic Commitment

Differences between individualistic and collectivistic cultures shape the way people view intimate commitments. In collectivistic cultures, family considerations and opinion have a much stronger influence than they do in individualistic cultures in determining whom people decide to marry, as well as whether or not they stay in the relationship (Dion & Dion, 1996).

Take China as an example. In Chinese culture, two fundamental values are xiao (loosely translated as filial piety—

Different cultures, different customs. Marriage and weddings are often construed very differently in different cultures. The relatively collectivistic culture of China prescribes different norms and expectations for both entering into and staying committed to a close relationship.

[Oliver Strewe/Lonely Planet Images/Getty Images]

568

The fairy-

Does this mean that people are more happily married in India or other countries where arranged marriages are prevalent? Not necessarily: Evidence suggests it can go either way. In China and Turkey, for example, partner-

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

Historical Differences in Long-

Historical Differences in Long-

Like the study of cross-

People hook up more frequently without any expectation of a long-

Thus, what was once viewed as deviant and illegitimate is now becoming more commonplace and turning into a cultural norm. These changes are important because we rely on cultural norms to interpret what is normal and how we should conduct a relationship. But some of the changing norms can lead to erroneous expectations about relationships. For example, high school seniors now believe that it is a good idea for a couple to cohabit for a while before marriage. Yet research shows that cohabitation does not make it more likely that a subsequent marriage will be successful. If anything, cohabitation prior to marriage is associated with a greater likelihood of divorce, although the reasons for this remain unclear (Dush et al., 2003; McGinnis, 2003).

Of course, cultural change does not occur in isolation but in the context of, and in part because of, changes in the economic, technological, and population landscape. For example, whereas marriage traditionally was fueled in part by economic concerns, this is now less the case. Women’s role in the workplace is changing the relationship context, with women becoming less reliant on a husband’s financial contributions. Indeed, nations tend to tolerate more divorces as those countries become more industrialized and there are fewer gender disparities in the workplace. For example, as China has moved toward a market economy, the divorce rate has steadily risen (Wang, 2001).

Cultural, economic, and technological changes have contributed to what Finkel and colleagues (2014) characterize as three dominant models of marriage. They argue that from the late 1700s to the mid-

569

570

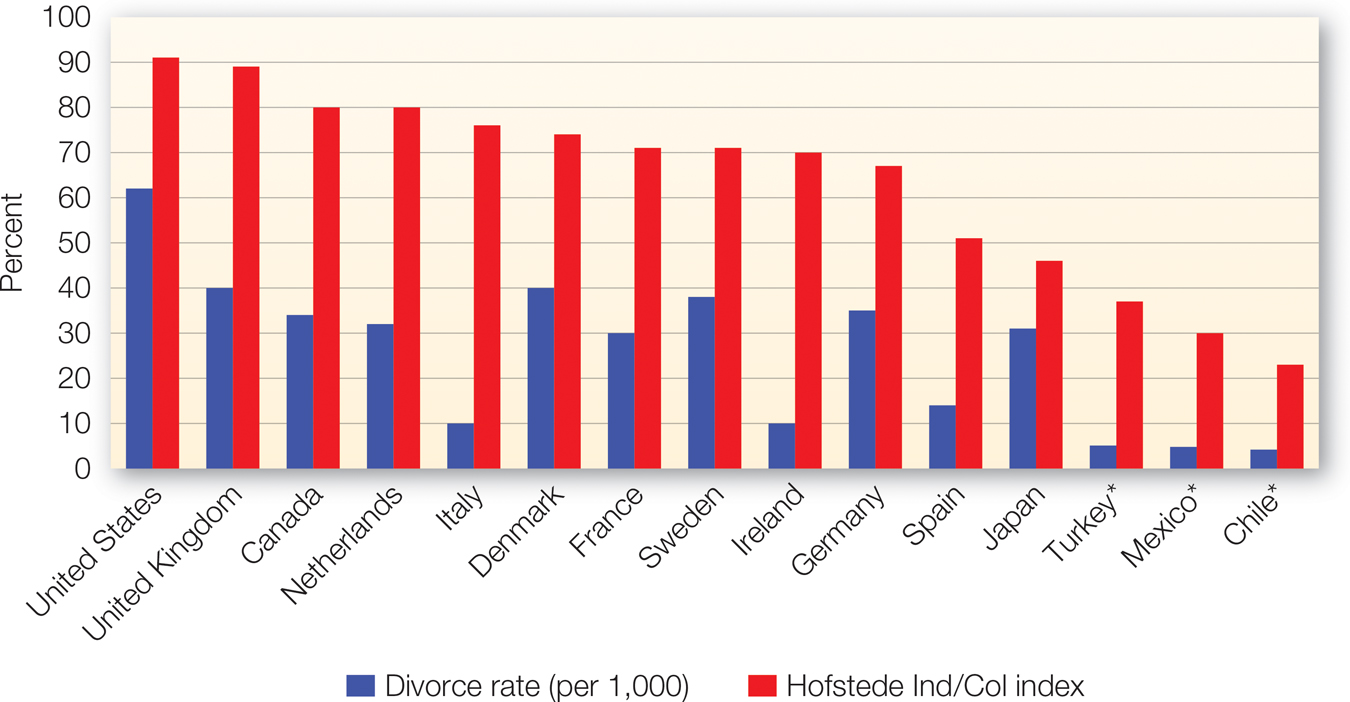

FIGURE 15.7

Divorce Rates in Different Countries

Why do different countries have different rates of divorce? Some research suggests that a critical factor is the level of individualism or collectivism of a culture. Individualistic cultures, such as the United States, tend to have higher divorce rates than more collectivistic cultures, such as Mexico. Note: Divorce rate is per 1,000. In the Hofstede Individualism/ Collectivism Index, higher numbers indicate more individualistic countries.

[Data sources: Divorce rate: Data from U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2011, International Statistics, Table 1336, Marriage and Divorce Rates by Country: 1980 to 2008, U.S. Census Bureau (2012), retrieved from http:/

Culture and Similarity in Friendship

Think ABOUT

Think about what it is to be friends with someone. Do you prefer your friends to be similar to you, sharing your religious beliefs, political views, and lifestyle? As you’ll remember, individuals are attracted to others with similar attributes to their own. To be sure, people from cultures all over the world are more attracted to similar than to dissimilar others. It is interesting to note, however, that the degree of similarity between friendship partners tends to be lower in East Asian societies, such as Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, than it is in North American settings (Igarashi et al., 2008; Kashima et al., 1995; Uleman et al., 2000). This is true of both actual levels of similarity and perceptions of similarity. What’s more, whereas similarity plays a major role in determining relationship quality in the United States, it is much less tied to relationship quality in East Asian countries (Heine & Renshaw, 2002; Lee & Bond, 1998).

The distinction between individualist and collectivist cultures helps explain these differing views on the importance of similarity. If you view yourself as independent and thus free to make friends with whomever you want, then why not pursue others who like what you like, validate your beliefs, and share your lifestyle? If you find that they are not quite similar enough, that’s no problem: You have hundreds of other people to choose from. In contrast, individuals in collectivist cultures experience the self as constrained by norms and obligations imposed by family and society as a whole. They do not feel so free to create friendships and are less likely to enter into friendships that are based solely on similarity. As a result, friends in these cultures may be more dissimilar.

|

Cultural and Historical Perspectives on Relationships |

|

Differences in romantic commitment Historical differences in the United States and cultural differences across the world suggest that love is not always the central basis of marriage. In collectivist cultures, family considerations have more influence on choice of marriage partners than in individualist cultures. |

Culture and similarity in friendship Differences in individualist and collectivist cultures affect whether or not similarity is important in a friendship. People in collectivist cultures may be constrained by norms and obligations, feeling less free to form friendships, and so are less likely to rely on similarity. |

|---|