15.5 The Time Course of Romantic Relationships

Although romantic relationships progress in a variety of ways, some theories and research programs illuminate certain commonalities in how relationships change over time. As we have done throughout this chapter, we will generally discuss these issues without focusing on the sexual orientation of the partners in the relationship. To be sure, the vast majority of relationship research has been conducted with heterosexual couples, and this can be an important factor to keep in mind. At the same time, however, the factors that influence relational commitment and satisfaction have generally been found to be similar among same-

571

Self-disclosure

FIGURE 15.8

Self-

Murstein’s stimulus-

[Data source: Murstein (1987) © 1987 Blackwell Publishing Inc. Reprinted by permission.]

Imagine two people meeting for the first time. During this initial stage of a relationship, people engage in varying degrees of self-

Self-disclosure

The sharing of information about oneself.

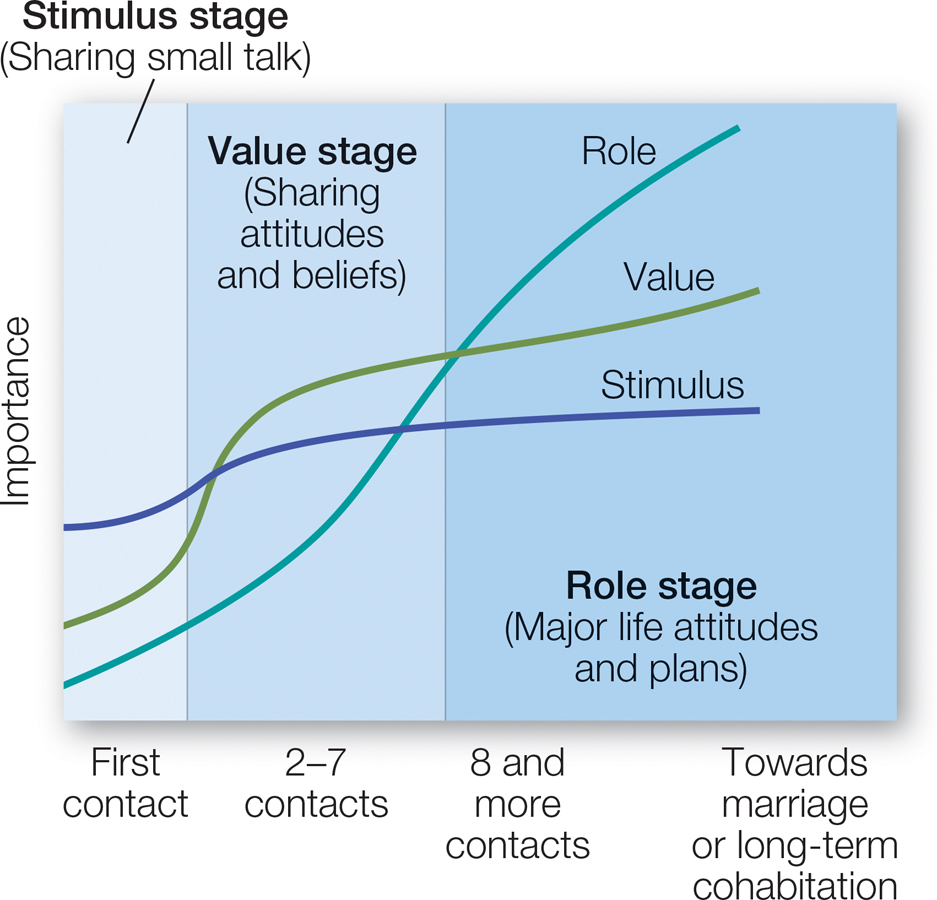

It turns out that relationship partners share different types of information about themselves at different stages of the relationship. According to Bernard Murstein’s (1987) stimulus-

If the relationship progresses beyond these first impressions, partners enter the value stage, in which they share their attitudes and beliefs (about religion and sex, for example). This stage helps them to decide whether they are sufficiently compatible to continue the relationship. It is generally only later, after partners have been committed to each other for a while, that they begin communicating about their roles, meaning their attitudes and plans when it comes to major life tasks such as parenting and establishing a career.

Research suggests that these stages are not really that discrete or orderly (e.g., Brehm, 1992). Some couples get into values and roles early in the relationship; some may discuss roles before getting to know their values. However, Murstein’s model is useful when we think about how relationships progress and the types of shared knowledge that matter. One consequence of sharing different types of information at different stages of the relationship is that partners may not be aware of differences that can create problems down the road. In the budding stages of a new relationship, during the value stage, people learn about each other’s likes and dislikes. Having found someone who shares their interests in cuisine, entertainment, and politics, they may believe that they have finally found the one. It may not be until they are together for a long time that they learn of incompatibilities in, for example, role expectations. Of course, for some couples this can be a time when partners discover how truly compatible they are and that they share a foundation from which their relationship can grow.

Rose-colored Lenses?

Another reason that people in a new romantic relationship often believe that they have found the perfect partner is that they perceive their new partner through rose-

572

In a similar manner, people show a powerful tendency—

Positive illusions

Idealized perceptions of romantic partners that highlight their positive qualities and downplay their faults.

To illustrate, in one line of studies people wrote about their partner’s greatest fault (Murray & Holmes, 1993, 1999). People judged their partner’s faults to be less important than outside observers judged them to be. Also, they focused on the bright side of their partner’s faults. For example, a woman might write that although her boyfriend got upset easily, that behavior reflected his exceptionally passionate and vivacious personality. Similarly, people offered “yes, but” interpretations of their partner’s faults—

You might be asking yourself, Is it really such a good idea to put our lovers up on a pedestal? Aren’t we setting ourselves up for crushing disappointment when our partners inevitably fail to live up to our idealized perceptions of them? The answer hinges on just how removed from reality people’s positive illusions are (Neff & Karney, 2005). If people are projecting positive qualities onto their partners that they simply don’t have, then they likely are setting themselves up for disappointment (Miller, 1997).

On the other hand, if people are aware of their partner’s positive and negative qualities but interpret them positively, such illusions can benefit the relationship. Sandra Murray and her colleagues have shown that people who idealize their romantic partners are more satisfied and feel stronger love and trust (Murray & Holmes, 1993, 1997; Murray et al., 2000; Neff & Karney, 2002). In one study ( Murray et al., 1996), married couples and dating partners were asked to rate themselves and their partners on their positive and negative qualities. They also were asked to indicate how satisfied they were in the relationship. Idealization was measured by the participants’ tendency to overestimate their partner’s positive qualities and underestimate their faults, compared with the partner’s ratings of him-

By idealizing our partner, we are likely to view his or her qualities and behaviors as all the more rewarding—

573

Furthermore, these positive perceptions also can motivate people to reach for the ideal with which they are perceived, and thus grow and develop in ways that are appreciated by their partners. When Murray and colleagues (1996) followed couples over time, they found that in more satisfied relationships, the partners came to perceive themselves more as they initially were idealized to be. This may partly reflect the operation of self-

Adjusting to Interdependency

FIGURE 15.9

Relationship Satisfaction Changes With Level of Involvement

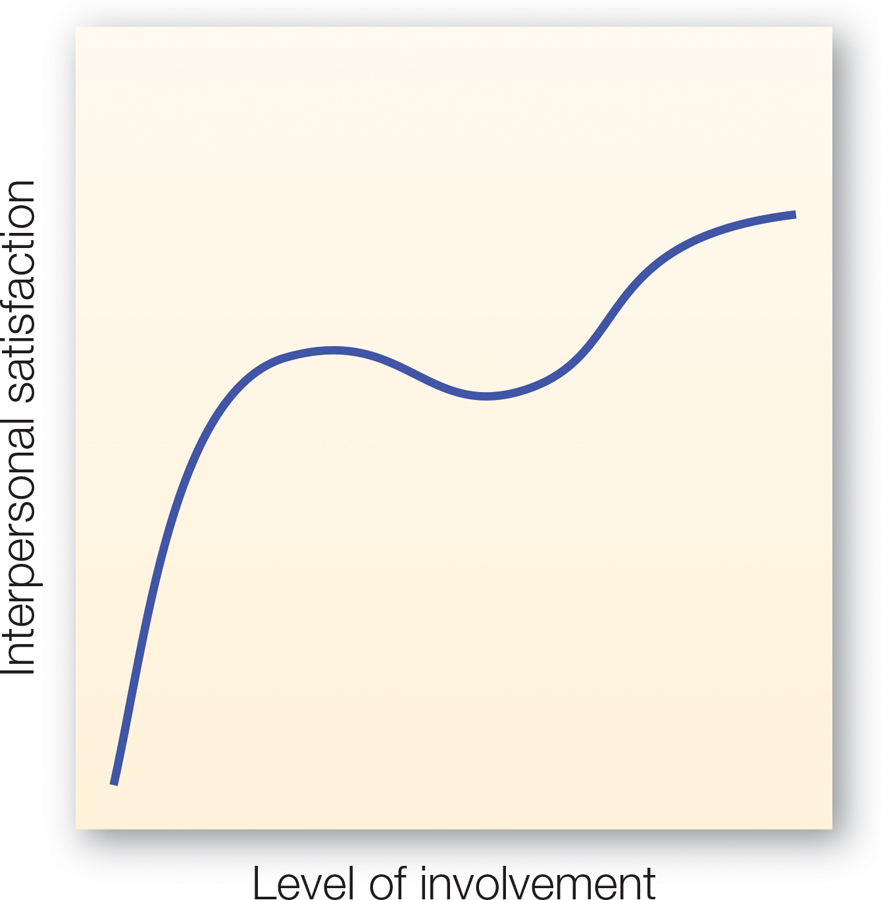

The beginning of a romantic relationship typically is marked by a rapid rise in satisfaction. Soon after, though, satisfaction levels off, most likely because the partners are adjusting to their increasing interdependence. If the relationship survives this turbulent period and the partners accommodate to each other’s needs and lives, the couple enjoys even more satisfaction, albeit at a more gradual rate.

[Data source: Eidelson (1980)]

So far, we have seen that early in the relationship, partners disclose in a way that obscures potential incompatibilities, and they view each other through the rose-

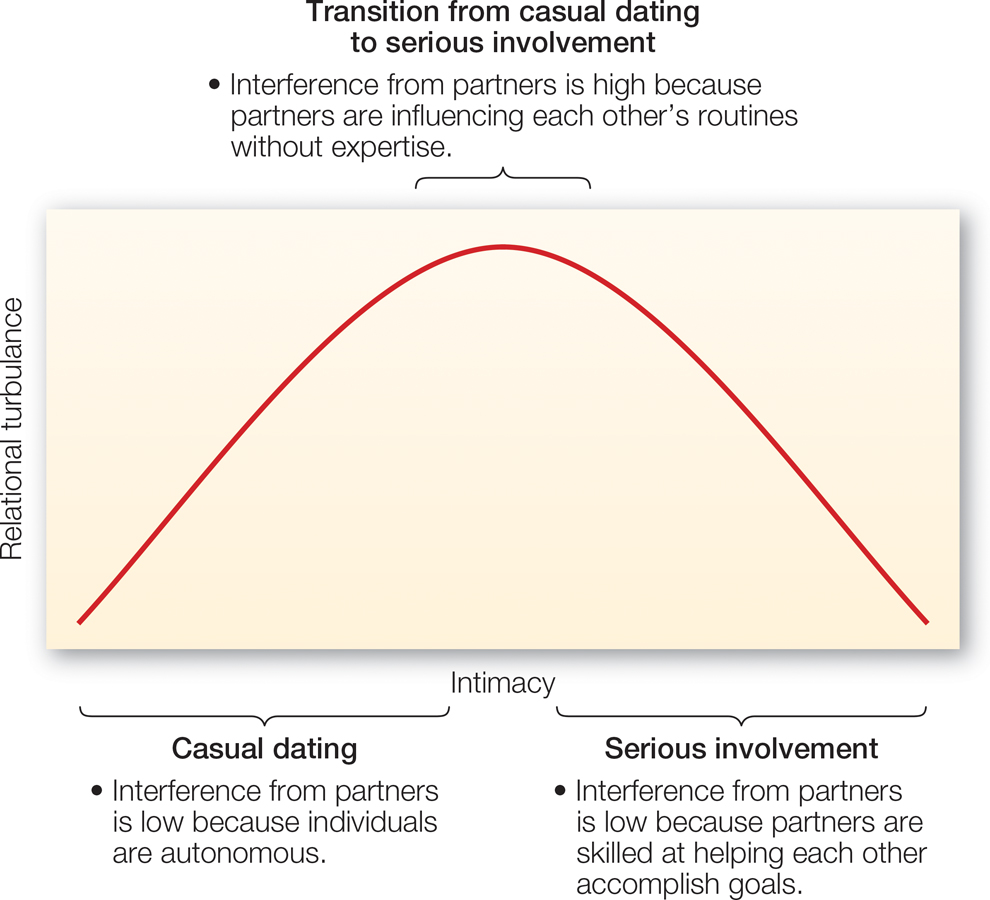

Why? According to the model of relational turbulence proposed by Solomon and Knobloch (2004) (FIGURE 15.10), in the early stage of a relationship there is little conflict, largely because partners are relatively independent and thus do not interfere with each other’s routines or goals. But as partners make the transition from casual dating to more serious involvement in the relationship, they go through a turbulent period of adjustment and turmoil (Knobloch & Donovan-

Model of relational turbulence

The idea that as partners make the transition from casual dating to more serious involvement in the relationship, they go through a turbulent period of adjustment.

FIGURE 15.10

The Relational Turbulence Model

The level of turbulence in a new relationship increases as the partners become more interdependent, spending more time together and interfering with each other’s routines. If the partners stay together and negotiate how to facilitate each other’s goals, then turbulence declines.

[Data source: Knobloch & Donovan-

574

If the partners stay together and learn how to adjust to their increasing inter-

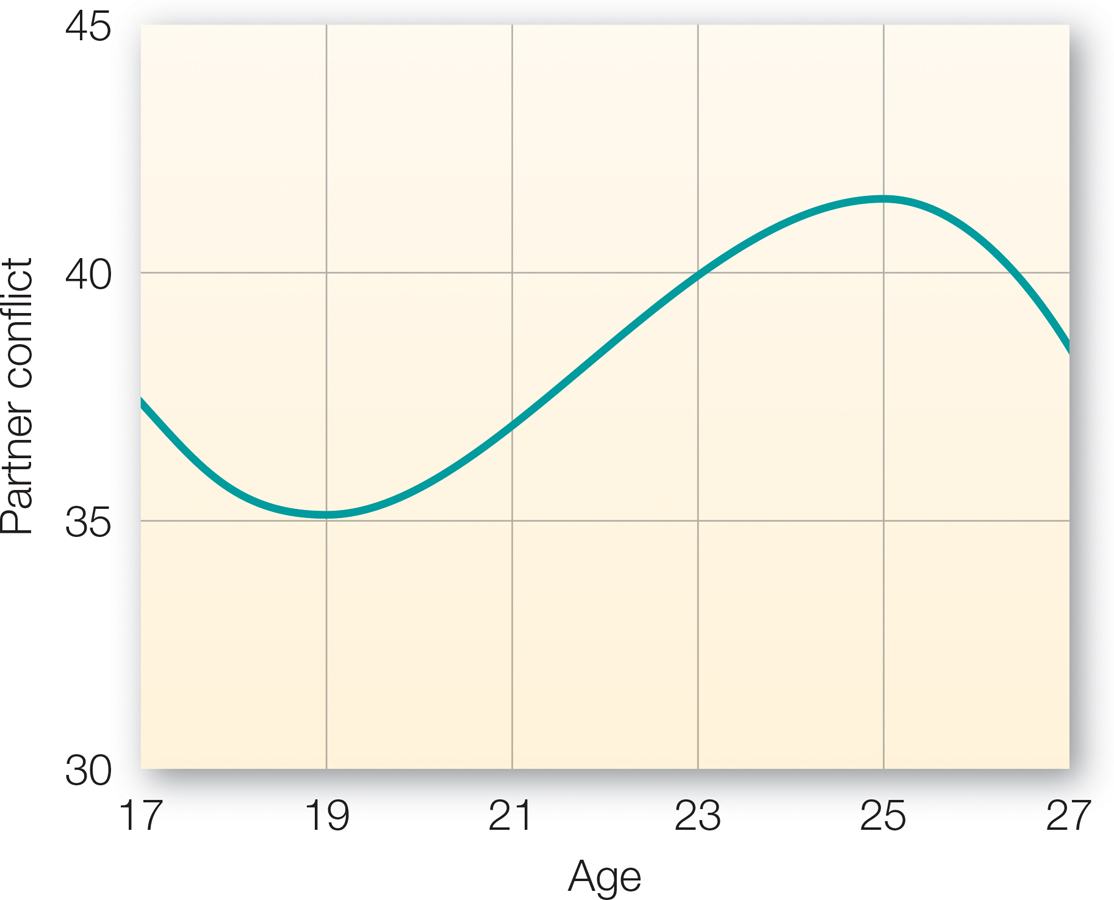

FIGURE 15.11

Romantic Conflict in Young Adulthood

Many people begin romantic relationships in their mid-

[Data source: Chen et al. (2006) © 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Reprinted by permission.]

This model helps to explain why conflict in romantic relationships is particularly high during the period of young adulthood. As you can see in FIGURE 15.11, the frequency of conflict increases as people go from their late teens to their mid-

This pattern occurs most likely due to the fact that, during their mid-

Let’s say a couple has made it through the turbulence caused by adjusting to interdependency, and they have struck a workable balance between their motives for independence and belonging. They decide to get married, pledging to spend the rest of their lives together. We can now expect that they will live happily ever after, enjoying the same or even higher levels of satisfaction. Right?

Marital Satisfaction?

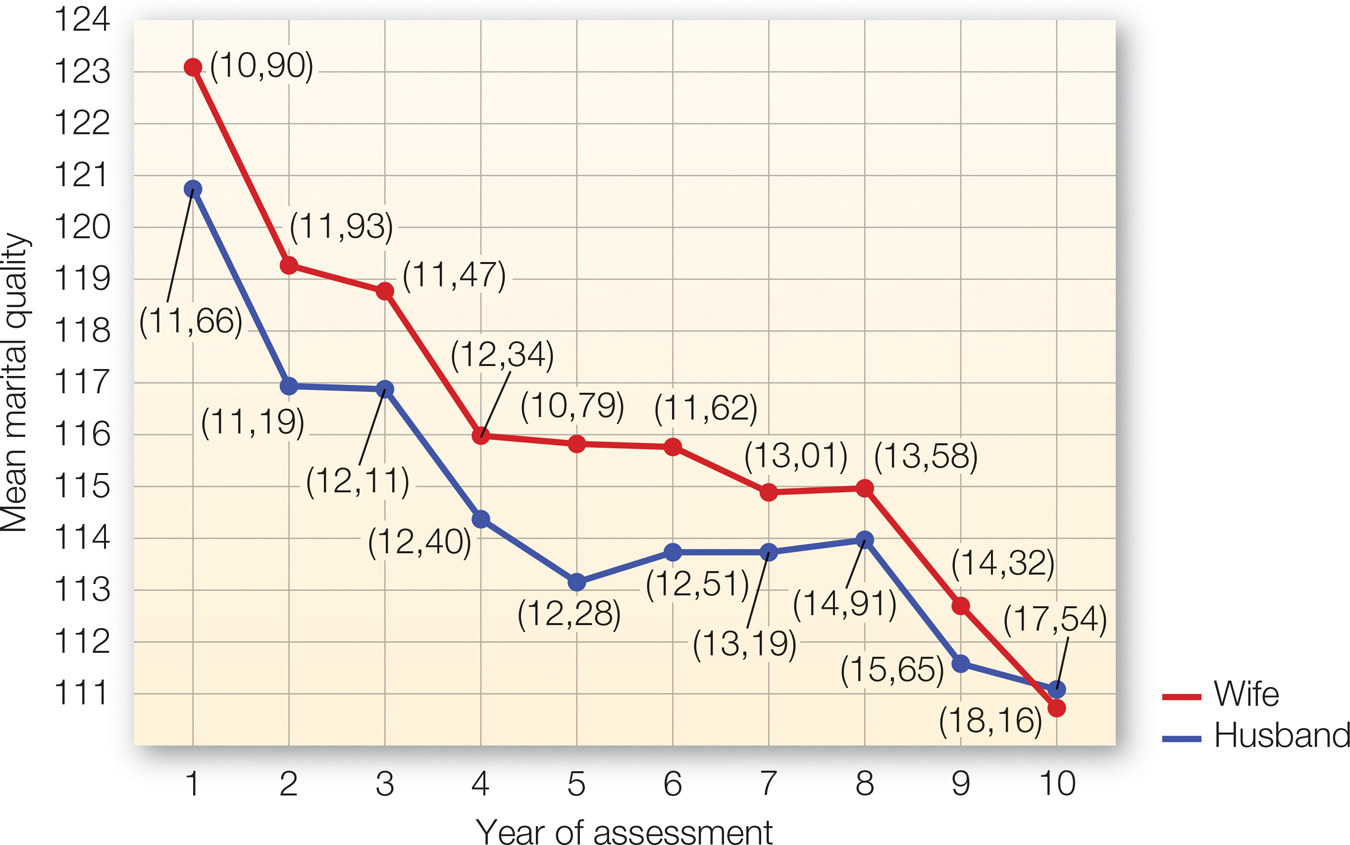

Unfortunately, research shows that, in most cases and even despite the partners’ good intentions, the prognosis for the course of the marital relationship is not so blissful as most couples expect it will be when they tie the knot. In one of the more comprehensive studies of marital satisfaction, Huston and colleagues (2001) followed dozens of spouses who married in 1981. Relationship satisfaction steadily declined for both husbands and wives as the years ticked by (see FIGURE 15.12). It’s unlikely that the married couples in this study were particularly hard to please: Other studies show a similar overall decline in ratings of marital quality (Karney & Bradbury, 2000; Kurdek, 1999). Of course, not all couples experience the same rate of decline, but most do (Kurdek, 2005).

FIGURE 15.12

The Trajectory of Marital Satisfaction

Most newlyweds presume that their marriages will become more and more satisfying over time, but statistics suggest that on average, satisfaction actually tends to decline over time.

[Data source: Kurdek (1999)]

Marital satisfaction tends to take a particularly steep dive at two points (Kurdek, 1999). The first drop occurs within the first year of marriage; the second occurs at about the eighth year of marriage (Kovacs, 1983). The big question, of course, is what causes the decline in marital satisfaction once the honeymoon is over. Although many important factors are involved, let’s focus on six important ones.

575

Slacking Off

When two people start dating, they go to a lot of trouble to be—

Small Issues Get Magnified

Interdependency acts like a magnifying glass, exaggerating conflicts that do not exist in more casual relationships. Why? Because we spend so much time with our romantic partners and depend so heavily on them for unique and valuable rewards, they have the power to cause us more pain and frustration than anyone else can. Indeed, spouses can stress each other out even if they do not intend to do so. For example, people are more negatively affected by their intimate partner’s cranky moods (Caughlin et al., 2000) and work-

Sore Spots are Revealed

As we mentioned, increasing levels of intimacy are closely associated with self-

576

Unwelcome Surprises Appear

Although couples might recognize their incompatibilities when they choose to get married, it’s often the surprises down the road that dampen marital satisfaction. These surprises tend to fall into two general categories. First, we can be surprised to learn the truth about things we thought we knew. One clear example of this is what are called fatal attractions (Felmlee, 2001). Qualities that we initially found attractive in the other person gradually become irritating or disappointing. Although, as we mentioned, newlyweds initially idealize each other (Murray et al., 1996), positive illusions usually wear off over time. For instance, at first you liked the fact that your partner was spontaneous and fun, but now he seems irresponsible, flaky, and childish. Or perhaps you initially celebrated your partner’s high level of attention and devotion, but after a couple years you come to resent the same behavior when it seems overly possessive and clingy. It’s not that partners are unaware of each other’s fatal qualities when they choose to marry. Rather, they fail to appreciate how their attitudes toward those qualities will change after a few years. Needless to say, these unexpected shifts in attitudes can take a bite out of marital satisfaction (Watson & Humrichouse, 2006).

A second category of unwelcome surprises occurs when married couples discover things that they did not know or expect at all. A good example is offered by the realities of parenthood, which, along with money, is the biggest source of marital conflict (Stanley et al., 2002). Most newlyweds, if they plan to have children, presume that parenthood will be enjoyable and bring them closer to each other. But most soon discover that parenthood, though wonderful at times, takes a significant toll on their marital satisfaction. Parents often underestimate how much time their children will demand, and therefore how little time they will have to enjoy each other’s company (Claxton & Perry-

How do we know that this decline in satisfaction is related to the stress of having and raising children? For one, cohabitating couples without children do not show the same dip in satisfaction as their heterosexual, child-

Partners Have Unrealistic Expectations

Good relationships demand a great deal more work and sacrifice than is typically portrayed in movies and on greeting cards. If a couple weds with unrealistically high expectations about the magic of marriage, they can feel cheated and disappointed later on, even if their relationship is healthy according to objective criteria (Amato et al., 2007). As we mentioned when discussing social exchange, satisfaction in close relationships depends on how well the partners’ current outcomes match their comparison level—

Passionate Love Loses Steam

A final reason satisfaction declines during the first years of marriage is that passionate love—

577

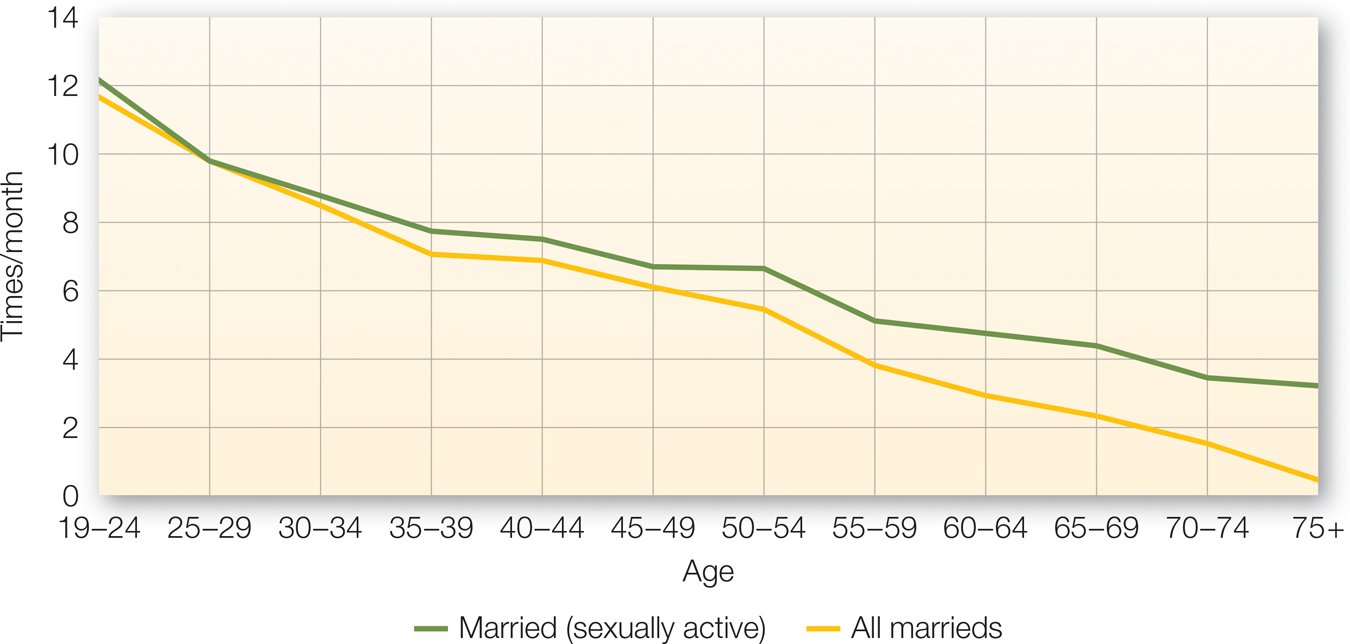

FIGURE 15.13

Frequency of Sexual Intercourse Over the Course of Marriages in the United States

As the years tick by in a marriage, the frequency with which the partners have sex tends to decline.

[Data source: Call et al. (1995) © 1995 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Reprinted by permission.]

Part of the reason for this dwindling of romance is that, over time, what was novel becomes less so. The sheer novelty of new love makes the partners especially arousing and exciting (Foster et al., 1998). Partners may continue to view each other with affection and sexual interest but the intensity of the arousal—

Here we see that the average couple has intercourse less and less frequently over the course of their marriage. In fact, some married couples have so little sex after age 50 that the researchers made a separate line just for married couples who have sex at least once a month (Call et al., 1995). Couldn’t this decline occur simply because the spouses are getting older? Although advancing age is indeed a factor, evidence also shows that people who remarry (and thus experience the novelty of a new partner) increase their frequency of intercourse, at least for a while (Call et al., 1995).

When the Party’s Over…The Breakup

For these and many other reasons, relationships often do end. As we will see later in this chapter, some estimates place the U.S. divorce rate near 50%. A much higher percentage of even serious dating relationships will ultimately come to a close. What are some of the consequences of the breakup for the individual? Even for the “dumper” as opposed to the “dumpee,” a breakup often exacts a severe toll on overall well-

The two major emotions that people experience in the face of a breakup are anger and sadness. Anger typically is pretty strong at first but diminishes somewhat quickly, whereas sadness may not be so severe initially but will diminish more slowly. Of course, the strength of these emotions depends on the importance of the relationship, the circumstances of the breakup, and how quickly the individual can accept it. Those who maintain love for the partner and are unable to accept the dissolution of the relationship recover much more slowly from these negative emotions (Sbarra, 2006). Recall our discussion of self-

578

Who is best able to come to terms with the dissolution of a relationship? A person’s level of attachment security plays a pivotal role. Those who are higher in attachment anxiety cling more tightly to the relationship. The hope of rekindling the extinguished flame allows the negative emotions to persist. In contrast, more securely attached people generally are better able to accept the breakup and so recover from sadness more quickly (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

Perhaps when getting dumped by an ex, you’ve heard the line that your now ex-

In addition to causing an emotional upheaval, a breakup can also jar our sense of who we are, blurring our sense of self and ultimately instigating a redefinition of our self-

So what can you do to facilitate the recovery process? We previously mentioned that recurring contact with the ex probably is not a good idea, but that engaging in alternative activities and investments is. In addition, research suggests that you also should strive to have compassion for yourself, that is, to love and appreciate yourself and be aware of your place in a shared humanity. When Dave Sbarra and colleagues (2012) studied divorcing couples, they audiotaped the participants talking about the divorce for four minutes, and later had judges rate the participants’ level of self-

Are We All Doomed, Then?

All of this can seem depressing, but it shouldn’t be. The processes we’ve described—

579

Of course, some committed romantic relationships end in a few years, some last but become less and less satisfying, and others remain satisfying and passionate for a lifetime. Even in marriages where the passion has dwindled, older couples sometimes continue to express deep companionate love for each other that can keep them genuinely happy (Hecht et al., 1994; Lauer & Lauer, 1985). Next, we’ll take a close look at factors that contribute to romantic relationships that dissolve and those that thrive.

|

The Time Course of Romantic Relationships |

|

Relationships change over time in common ways. |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Self– Partners share information about themselves gradually, so it may take a long time for some fundamental differences to emerge. |

Rose- Early on, the romantic partner may be idealized. This may lead to disappointment unless one is aware of— |

Adjusting to interdependency As independence evolves into interdependence, conflict may arise. Adjusting to interdependence creates a firmer footing for the relationship. |

Marital satisfaction? On average, marital satisfaction tends to decrease over time, especially after the first year and after the eighth year of marriage. |

The breakup Breakups result in anger and sadness, best healed by alternative investments and self- |

Doomed or not? The happiest couples start out with realistic outlooks about married life. |