1.3 Cultural Knowledge: The Intuitive Encyclopedia

How do we know what we know? According to Heider’s (1958) attribution theory, people are intuitive scientists. Like scientists, ordinary people have a strong desire to understand what causes other peoples’ actions. Heider suggested that we act as intuitive scientists when we observe other people’s behavior and apply logical rules to figure out why they acted the way they did. Heider labeled these explanations causal attributions. These attributions are based largely on cultural knowledge, a vast store of information accumulated within a culture that explains how the world works and why things happen as they do. This process of observing and explaining is such an integral part of our daily lives that we usually don’t even notice that we are doing it.

Think ABOUT

Think about the last time you caught a cold. What explanations of how you caught it did you consider? You probably tried to remember whether any of your recent contacts showed any signs of sneezes or sniffles, because our culture, informed by medical science, tells us that colds are transmitted by viruses or germs carried by other people suffering from colds. But the explanations provided by cultures vary over time, and different cultures explain things in different ways. Your grandparents probably would have thought back to instances in which they were caught in the rain or experienced a draft or a rapid change in temperature. Someone living in ancient Greece might have wondered about whether the various humors of her body were out of balance. And members of many traditional cultures would consider the possibility that they had offended the spirits.

Attribution theory

The view that people act as intuitive scientists when they observe other people’s behavior and infer explanations as to why those people acted the way they did.

Causal attributions

Explanations of why an individual engaged in a particular action.

Cultural knowledge

A vast store of information, accumulated within a culture, that explains how the world works and why things happen as they do.

Such cultural wisdom is passed down across generations and shared by individuals within cultures. Sometimes, when the answers we seek aren’t part of our readily available cultural cupboard of knowledge, we consult experts: wise men, priestesses, or shamans in ancient times; physicians, ministers, psychotherapists, or online bloggers in modern times. In other words, a good deal of our understanding of the world comes from widely shared cultural belief systems and the words of authority figures who interpret that knowledge for us.

Asking Questions About Behavior

When trying to explain the specific actions of specific people, expert opinions are not always helpful. In these circumstances, you might think that the best way to explain a person’s behavior is simply to ask them for their motives. How many times have you asked someone, “Why did you do that?” or, “What were you thinking?” How many times have you fielded similar questions from others? We’ve all acquired valuable insights about people’s behavior by asking them to explain themselves. After all, people can reveal things about themselves that no one else can know. Similarly, we can ask ourselves about the causes of our own behavior and draw on sources of information to which only we have access. We all have rich memories of our personal histories and awareness of our thoughts, feelings, and other private experiences to which no one else is privy. Unfortunately, people’s explanations for their own behavior can be misleading. Here are a couple of reasons why.

11

People Don’t Always Tell the Truth

When are you not honest with yourself? For many weight-

[Bodrov Kirill/Shutterstock]

We do not deal much in fact when we are contemplating ourselves.

— Mark Twain, “Does the Race of Man Love a Lord?” (1902)

Often, people are not honest about why they acted a certain way. Because we depend on other people for so many of the things we need in life, we care a great deal about the impressions they form of us. So although people may be forthright when asked to report their hometown or college major, they may be less candid when answering questions about their weight, age, GPA, or sexual proclivities. As we’ll see in later chapters on the self and interpersonal relations, people have a variety of motives for not telling the truth.

People Often Don’t Really Know What They Think They Know

Our accounts of our own behavior are often inaccurate, even when we believe we are telling the truth. Sometimes, powerful psychological forces may block awareness of our motives. Erich Fromm (1941) described a clinical example of such repression in the case of a young medical student who seemed to have lost interest in his classes. When Fromm suggested that the student’s interest in medicine seemed to be wavering, the student protested that he had always wanted to be a doctor. Several months later, however, the student recalled an incident from childhood when he was playing with building blocks and happily announced to his physician father that he wanted to be a great architect when he grew up. Upset that his son didn’t want to follow in his own footsteps, his father ridiculed architecture as a childish profession and insisted that his son would grow up to be a doctor as he was. So the future medical student repressed his desire to practice architecture, and decades later sincerely believed he was in medical school because he wanted to be there.

The prevalence of this kind of repression continues to be debated, but social psychological research has shown that even without repression, people often can’t explain their own actions and feelings because they simply do not know why they do what they do or feel the way they feel. People are routinely inaccurate even when explaining their most mundane and innocuous activities. In a classic paper published in 1977, Richard Nisbett and Tim Wilson proposed that when people are asked why they have certain preferences or are in the mood they are in, they usually generate answers quite readily, but such explanations are often based either on a priori (i.e., preexisting) causal theories acquired from their culture or on factors that are particularly prominent in their conscious attention at that moment. These sources of information often lead us to inaccurate explanations.

A priori causal theories

Preexisting theories, acquired from culture or factors that are particularly prominent in conscious attention at the moment.

To test these ideas, Nisbett and Wilson designed a series of studies that revealed participants’ reasons for their preferences, then compared them with participants’ own accounts of their behavior. We’ll go over more of these studies in chapter 5, but here is one example, conducted in the lingerie section of a large American department store. Individual female shoppers were shown four pairs of stockings arrayed in a row across a table, asked to select their favorite, and then explain why they preferred it over the others. In fact, the stockings were identical except for slight differences in scent. After each individual participated in the study, the stockings were shuffled and put back on the table so that the particular position of each pair of stockings varied randomly. As it turned out, the only factor that had any impact on the shoppers’ choices was where they were placed on the table. As marketing experts know, all other things being equal, people are likely to pick products that are placed at the end of a table (or an aisle in a grocery store). In this study, 71% of the participants chose the stockings on the right side of the table, regardless of which pair of stockings was in that position (presumably because people looked at the stockings from left to right, just as when they are reading in English). The women in the study were quite confident in the explanations they provided to justify their choices, such as perceived differences in color or texture, but not a single one of them suggested that her choice was determined primarily by where the stockings were positioned on the table. Yet this was clearly the most influential determinant of most of the women’s choices!

12

Research with both men and women has shown similar inaccuracies regarding what factors do and do not affect them in a variety of domains. For instance, people are inaccurate even in judging what determines their day-

Why are people so likely to give inaccurate explanations of their preferences and feelings? Nisbett and Wilson argued that the human capacity for introspection—

Think ABOUT

To get an intuitive sense of this, think of a time you had a craving for some food, say a burrito from your favorite Mexican take-

Explaining Others’ Behavior

If people often don’t even know why they do and feel things, it’s not surprising they are also limited in their knowledge of why other people do and feel things. Indeed, we generally don’t go through all that much effort in thinking about why people behave the way they do. For the most part, we tend to be a bit lazy when it comes to thinking and reasoning, a tendency that has led some social psychologists to suggest that people are cognitive misers who avoid expending effort and cognitive resources when thinking and prefer to seize on quick and easy answers to the questions they ask. If we think an explanation makes sense, we tend to accept it without much thought or analysis.

Cognitive misers

A term that conveys the human tendency to avoid expending effort and cognitive resources when thinking and to prefer seizing on quick and easy answers to questions.

However, when events are important to us or occur unexpectedly, we more carefully scrutinize our environment and the people in it to make inferences about how the world works and why the people around us are behaving the way they are. We might even go to the trouble of verifying our inferences with other people. Having decided what caused an event or another person’s actions, we then use these causal attributions to direct our own behavior. But even when we put the effort in, some major pitfalls in intuitively observing and reasoning can lead us to accept faulty conclusions about ourselves, other people, and reality in general.

13

Our Observations Come From Our Own Unique and Limited Perspective

One problem occurs when we make inferences based on observation of only part of an event or of an event viewed from a limited perspective. Imagine that you are a clinical psychologist doing a psychological assessment of a new client. You drive up to your client’s house to meet him for the first time and observe him in a rather ferocious verbal dispute with a man in his front yard. From this observation you infer that your client is a hostile and aggressive man. However, suppose that minutes before you arrived, the normally docile and peaceful client happened to discover this man running from the house with the client’s laptop under his arm. Seeing a broader range of your client’s behavior would almost certainly alter your judgment of his personality.

Thus, sometimes our judgments are based on incomplete observations, and we would make very different inferences if we could observe the entire event in question. For a historical example, consider the 6th-

Our Reasoning Processes May Be Biased to Confirm What We Set Out to Assess

A more fundamental problem is that we rarely are objective observers and interpreters of the world around us. One of the great lessons of social psychology is that everything we observe, through all of our senses, is influenced by our desires, prior knowledge and beliefs, and current expectations. This is confirmation bias, and put simply, it means our views of events and people in the world are biased by how we want and expect them to be.

Confirmation bias

The tendency to view events and people in ways that fit how we want and expect them to be.

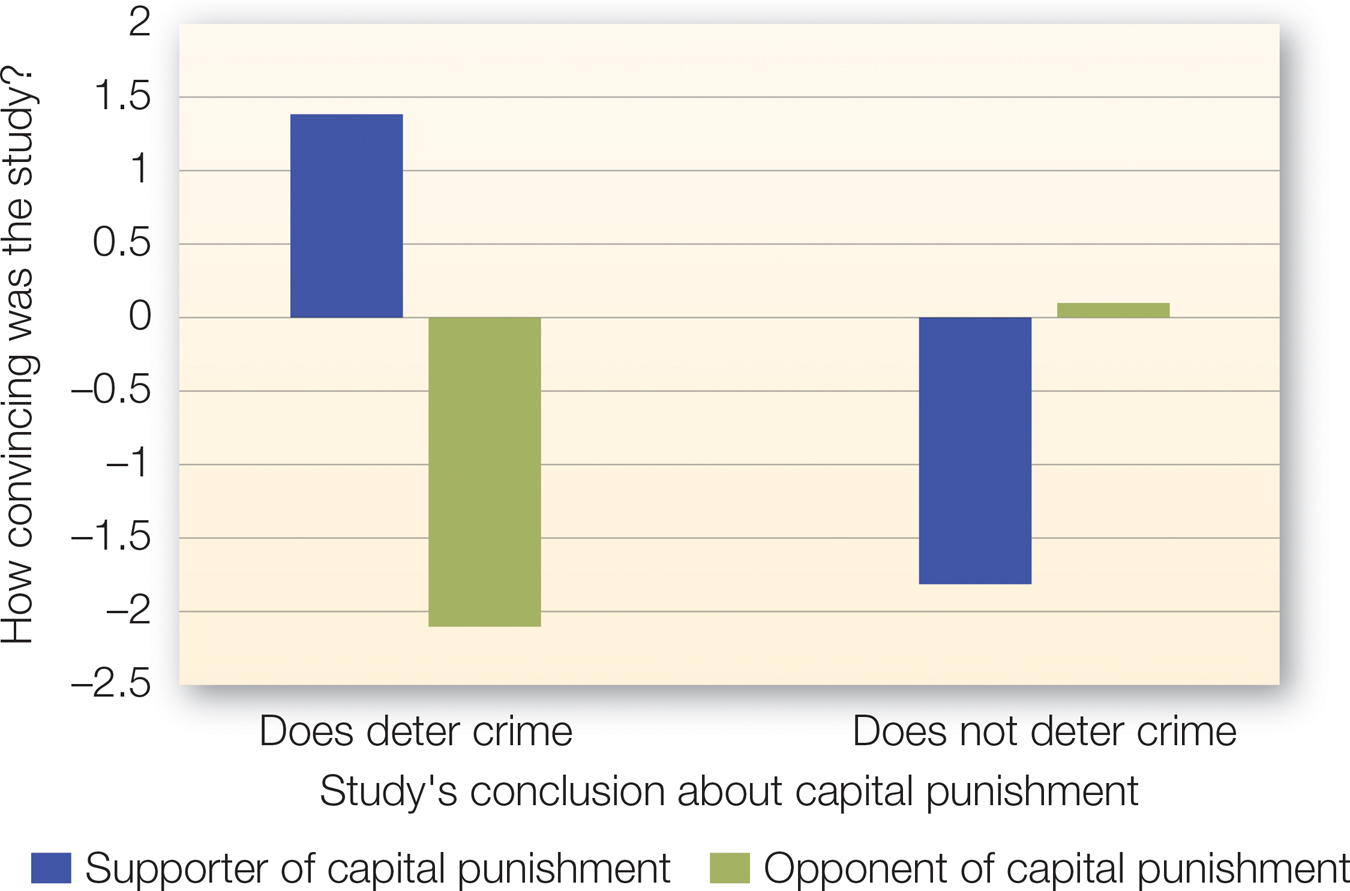

FIGURE 1.1

Confirmation Bias

When presented with evidence for and against capital punishment, people were more convinced by the evidence that supported their initial attitude.

[Data source: Lord et al. (1979)]

The tendency to reach conclusions that are consistent with our expectations and desires was demonstrated by Charles Lord and colleagues in 1979. They asked introductory psychology students to report their attitudes about some important issues so they could identify a subset who had strong feelings either in favor of, or opposed to, capital punishment. A few weeks later, this subset of students was recruited to participate in a laboratory study of how people evaluate factual information, although they were unaware of being selected because of their extreme feelings about capital punishment. The students then read summaries of two studies on capital punishment as a crime deterrent, one of which concluded that capital punishment reduced crime and the other that capital punishment is ineffective as a deterrent to crime. After reading the two studies, the students were asked to evaluate how well or poorly each study had been conducted and how convincing the studies’ conclusions were. Finally, everyone in the study reported his or her current attitude about capital punishment.

If perception is a direct reflection of reality, then all the students in the study should have pretty much agreed about the quality of the research they read, because they all were exposed to exactly the same materials. But this was not the case. Students originally in favor of capital punishment found the study demonstrating its effectiveness for reducing crime more convincing, whereas opponents of capital punishment were much more convinced by the research showing the ineffectiveness of capital punishment (see FIGURE 1.1). Regardless of their position on the issue, they found the study that confirmed their belief to be of higher scientific quality. In addition, students who favored capital punishment became even more favorable toward capital punishment after reading both studies, whereas those who opposed capital punishment became even more opposed to it after reading the same two studies. In other words, the students’ judgments of the same “reality” (the two studies) were dependent on their initial attitudes (for or against capital punishment), and the same “reality” caused them to change their attitudes in different directions (becoming more supportive of or opposed to capital punishment).

14

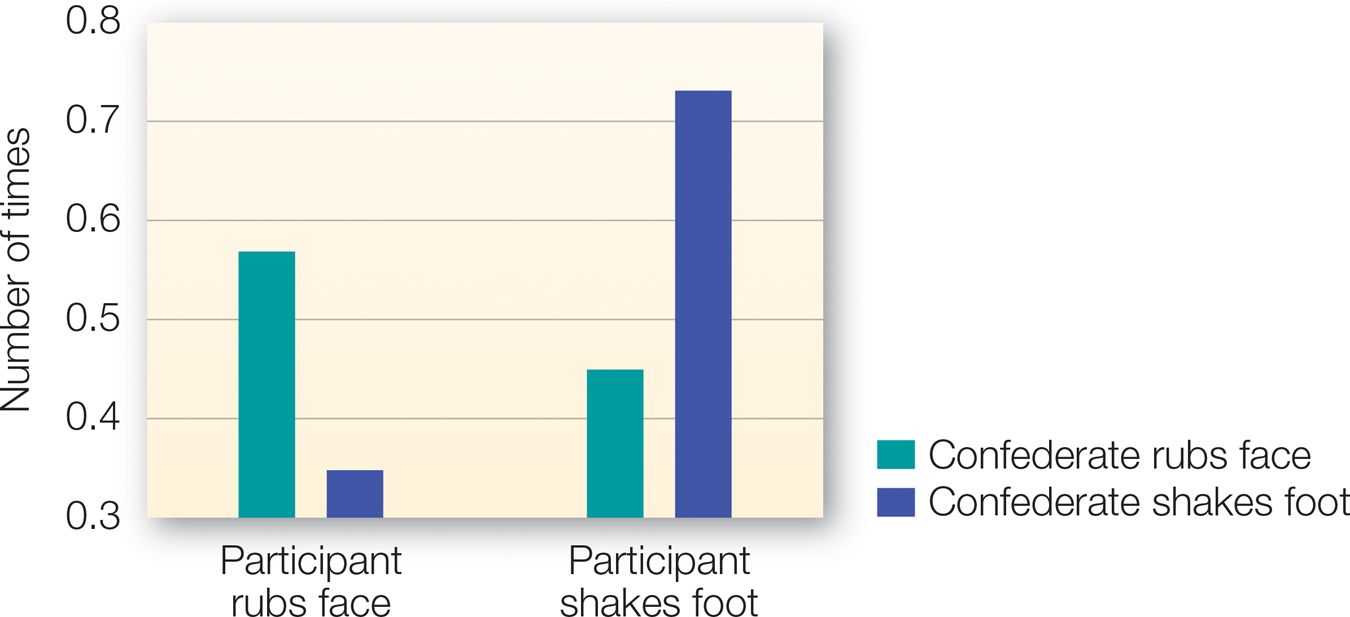

The Act of Observing May Change the Behavior We Seek to Explain

One final problem is that when people are being observed, the presence of the observer causes them to alter their behavior, sometimes knowingly but often unconsciously. What is observed, then, is the result, to some extent, of the presence of the observer. Consider a personnel manager for a large company who is reluctant to hire a job candidate who appeared fidgety at her interview. Examining a clever study by Tanya Chartrand and John Bargh (1999), we might question whether the personnel officer’s own inability to sit still actually made the job candidate seem so jittery. People in this study were asked to spend 10 minutes in two different sessions with one other participant. During each session, the pair looked at a picture and discussed whether it should be included in a psychological test. However, the supposed other participant in each session, unknown to the real participants, was a confederate, someone working with the experimenters. One confederate rubbed his or her head throughout the session; the other confederate tapped his or her foot repeatedly during the other session. Videotapes of the naive participants during the sessions were then shown to impartial judges with no foreknowledge of the study. The impartial judges found that the real participants tapped their feet more when they were in the room with the confederate with the happy feet, and rubbed their heads more when they were with the confederate with the itchy scalp (FIGURE 1.2). No one in the study realized that the person in the room with them during the sessions was influencing his or her behavior. This is just one example of many studies that have shown how observers unwittingly can be directly responsible for eliciting what they observe in others.

Confederate

A supposed participant in a research study who actually is working with experimenters, unknown to the real participants.

FIGURE 1.2

The Subtle Influence of Others

Number of times participants rubbed their heads and shook their foot per minute when with a confederate who engaged in one or the other behavior.

[Data source: Chartrand & Bargh (1999) © 1999 American Psychological Association. Reprinted by permission]

People often imitate each other without even realizing it.

[Getty Images/Flickr RF]

15

This all boils down to a simple conclusion: Basing psychological inferences on one’s own observations is a tenuous proposition. Sometimes we have a limited perspective and don’t see enough of an event to make a complete judgment. Sometimes our desires, prior beliefs, and expectations bias our perception. Sometimes our observations match reality reasonably well, but we’re partly responsible for what we’ve observed. Does this mean we should abandon observation as a way to learn about ourselves and the world around us? Quite the contrary: Careful observation is an essential aspect of scientific inquiry. We should take great pains to focus on what is happening in the world around us, but we can become better observers by understanding when and how our observations might be suspect and by using the scientific methods that have been developed to minimize the influence of these biases.

|

Cultural Knowledge: The Intuitive Encyclopedia |

|

People’s intuitive understanding of much of what happens in the world is derived from cultural knowledge. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Asking questions has limitations. People don’t always tell the truth. People often don’t know the truth. |

The intuitive mode of observing and reasoning is faulty. We often prefer quick and easy answers. Our inferences often are based on our own limited perspective and preexisting expectations. We may be biased to confirm what we prefer to believe. Observation itself may change a person’s behavior. |

|