2.1 Evolution: How Living Things Change Over Time

Probably all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from some one primordial form, into which life was first breathed. . . . [W]hen we regard every production of nature as one which has had a history . . . every complex structure and instinct as the summing up of many contrivances, each useful to the possessor . . . how far more interesting . . . will the study of nature become! . . .

In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation.

—Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species

To get to the roots of human nature, let’s begin, well, at the beginning. Planet Earth arrived on the galactic scene roughly 4.6 billion years ago. Within a billion years after that, conditions were ripe for the appearance of a completely unique and unprecedented form of matter—

Evolution

The concept that different species are descended from common ancestors but have evolved over time, acquiring different genetic characteristics as a function of different environmental demands.

Natural selection

The process by which certain attributes are more successful in a particular environment and therefore become more represented in future generations.

Natural Selection

Perfectly self-

Mutation: Random mistakes in DNA replication that caused variations. Most were maladaptive, leading to an almost immediate end to the organism’s life. However, some were adaptive, which means that they actually improved the resulting organism’s chances of surviving and reproducing.

Sexual recombination: When a new creature is produced, it does not have the exact same genetic makeup as the creatures that produced it but has a combination of its parents’ genes.

The second key ingredient for evolution by natural selection is competition. In a world of limited food, mating partners, and other resources, even infinitesimally small variations might help an individual compete more effectively, at first with other “primal creatures” and eventually with other species vying for the same resources in the same environments.

39

Variability and competition in particular environments determine which genes are passed along to subsequent generations through reproduction. These genes influence each individual organism’s physical and behavioral attributes. Those creatures that possess attributes that improve their prospects for survival, reproduction, and survival of their offspring are more successful in passing along their genes, which, in turn, leads to the widespread representation of those attributes in future generations. These attributes are known as adaptations. Over time, individuals with the most successful adaptations outnumber and eventually replace less well-

Adaptations

Attributes that improve an individual’s prospects for survival and reproduction.

Survival of the Fittest: Yes, but What Is Fittest?

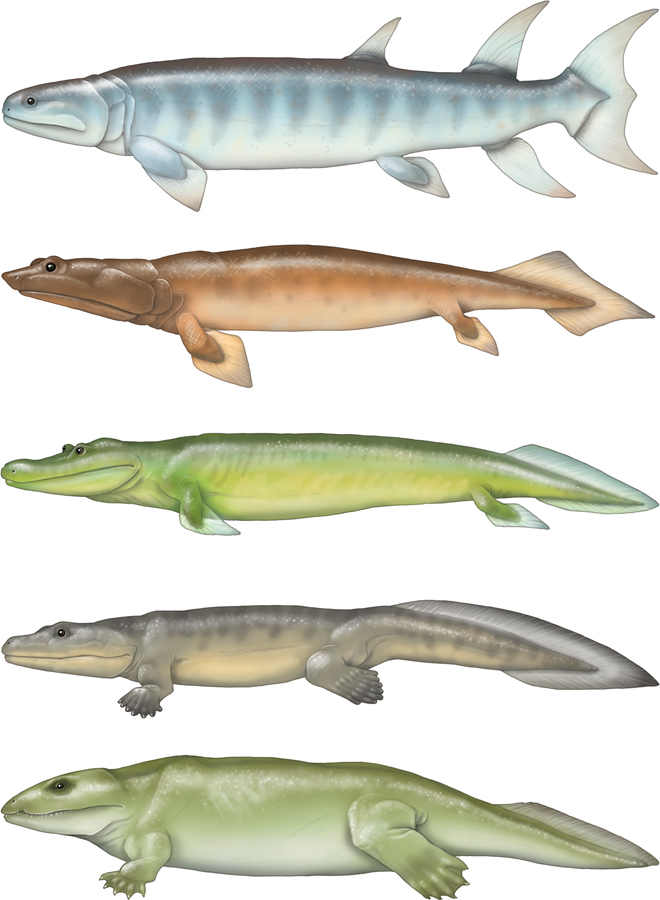

New species of amphibians evolved from fish as random mutations allowed for movement and survival out of the water.

The process of evolution by natural selection has often been characterized as the survival of the fittest. (Darwin himself never used this term; it was coined by Darwin’s contemporary Herbert Spencer in 1864.) However, “fittest” does not mean strongest or most aggressive. If it did, Tyrannosaurus rex would still be roaming the planet instead of merely posing in fossilized form for museum patrons. What is “fittest” depends entirely on the natural environments in which particular organisms reside. Creatures adapted for warmth would not be fit in cold environments, and vice versa, which is why you don’t find alligators and iguanas in Alaska or polar bears and penguins in Panama (except in zoos!).

Once new variants on a life form emerge, with new ways of exploiting an environmental niche for survival and reproduction, attributes that were once adaptive may become less adaptive. If these less useful attributes aren’t harmful, they may remain as harmless vestiges of early ancestors. Other attributes that might have been utterly useless to past generations may now acquire tremendous adaptive value. For example, if mutations cause individuals of an aquatic species to develop new ways of obtaining oxygen so that they can survive on dry land, what was functional for their ancestors (e.g., gills) may become utterly worthless. However, new variations—

Depictions of evolution in popular culture often describe “Mother Nature” as calling the shots, encouraging one species to realize its full potential while neglecting or punishing another species. But this is false. The process of natural selection just happens—

Naturalistic fallacy

A bias toward believing that biological adaptations are inherently good or desirable.

|

Evolution: How Living Things Change Over Time |

|

Evolution occurs through the process of natural selection, which is a consequence of variability and competition. |

The process of evolution leads to adaptations that improve the organism’s prospects for survival and reproduction in its current environment. |

What is adaptive depends on the interaction between the physical environment and the attributes of the organism. |

Adaptations are trade- |

|---|

40