2.3 Culture: The Uniquely Human Adaptation

Culture and history and religion and science [are] different from anything else we know of in the universe. That is fact. It is as if all life evolved to a certain point, and then in ourselves turned at a right angle and simply exploded in a different direction.

—Julian Jaynes (1920-

Our depiction of human beings up to this point is already fairly complex, but it is a one-

The third dimension is the cultural, which includes those aspects of each person that have been shaped by the particular culture within which she or he was socialized and that he or she currently inhabits. To round out our psychological depiction of humankind, we now turn to this profoundly influential aspect of human life—

52

What Is Culture?

The scheme of things is a system of order. . . . It is self-

—Allen Wheelis (1915–

Consider the present moment, right now, as you read this sentence. This is a moment of your conscious experience of life. It is a moment you will never experience again (perhaps thankfully). Now it’s gone, and you are on to another fleeting moment. Your conscious life consists of a continual sequence of such moments, interspersed with sleep, until your death. But is that generally how you conceive of time? Probably not.

Instead, we think of time in terms of minutes, hours, days, years, and so forth. Perhaps right now it’s 9:00 p.m. Well, there is another 9:00 p.m. every day. And perhaps it’s Tuesday—

Think ABOUT

What sets humans apart from other animals is that they spend the bulk of their waking hours (and even some of their time sleeping) embedded in a world of ideas and values that gives life meaning, significance, purpose, and direction. Think about what really matters to you, the things you aspire to, dream about, and probably sometimes worry about. For some it’s making the grade in school; for others it’s that new car that would feel so incredibly cool to drive. Some are obsessed with music, movies, or the arts, whereas others are wrapped up with nightlife and the club scene. Maybe spiritual values and the fate of the soul capture your attention, or the crazy goings-

Culture is a set of beliefs, attitudes, values, norms, morals, customs, roles, statuses, symbols, and rituals that is shared by a self-

Culture

A set of beliefs, attitudes, values, norms, morals, customs, roles, statuses, symbols, and rituals shared by a self-

55

The Common yet Distinctive Elements of Culture

All cultures have certain basic elements, and yet each culture’s version of these features is unique. The similarities among cultures are not surprising, given that, as we have noted, people everywhere have the same basic motivations, emotions, and cognitive capabilities, and must contend with the same basic realities of life on this planet. At the same time, different groups inhabit different physical environments and different cultural histories. As a result, each culture’s version of the basic elements is unique. These differences are what make meeting and learning about various groups of people from other parts of the world so interesting but also sometimes confusing or disturbing. Let’s briefly consider each of these elements and how they are similar and different across cultures.

53

Beliefs are accepted ideas about some aspect of reality. The idea that the earth revolves around the sun is a belief. Within a culture, many beliefs are virtually never disputed; these ideas are so unquestioned that they are often referred to as cultural truisms. In Western cultures, the aforementioned sun-

Beliefs are generally taken on faith and based on learning from parents, teachers, and other cultural authorities rather than being derived through specific personal experience. After all, if we relied only on personal experience, all but a few scientists and astronauts would believe that the sun revolves around the earth, as the vast majority of people once did. Similarly, how many people have seen the supposed proof that brushing teeth is good for us? The fact that we hold these and thousands of other beliefs on faith is a perfect example of how culture helps people in a group to create a shared sense of reality.

Members of a culture tend to share similar attitudes, which are preferences, likes and dislikes, and opinions about what is good and bad. Attitudes are closely linked to beliefs, but they refer more specifically to how people evaluate something as good or bad. For example, a group of people may share the belief that abortion is legal in the United States, but their attitude toward the legalization of abortion could be favorable or unfavorable.

A culture’s values reflect its members’ guiding principles and shared goals. Although cultures differ in their values, Shalom Schwartz and colleagues (e.g., Schwartz, 1992) has shown that cultures around the world recognize 10 core values (Table 2.1). These values can be viewed as stemming from the two basic motivational orientations mentioned earlier in this chapter: security and growth. The values of security, tradition, conformity, benevolence, and universalism reflect a desire to sustain safety, order, harmony, meaning, connection, and approval. In contrast, the values of self-

Across over 50 different cultures there is remarkable agreement in the importance people give each of these value types. Benevolence, the desire to be a good person ranked first; self-

|

|---|

|

[Research from: Schwartz & Bardi (2001) © 2001 SAGE. Reprinted by permission] |

54

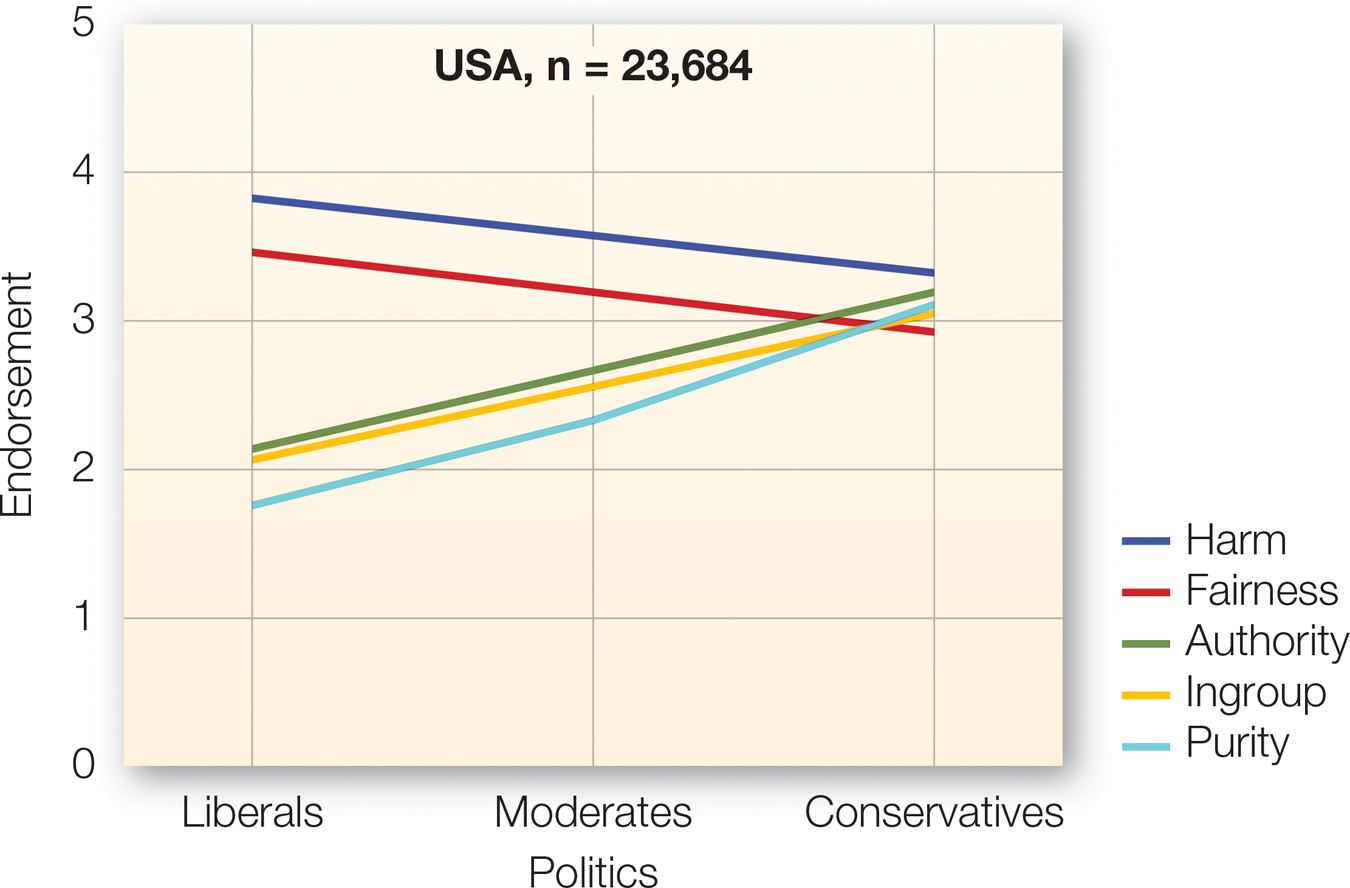

FIGURE 2.6

Moral Foundations

In the United States, individuals near the liberal end of the political spectrum value care and fairness above other possible moral foundations, whereas those near the conservative end emphasize all five moral domains.

[Data source: Graham et al. (2009)]

Values have a broad influence in a wide range of situations; in contrast, norms are shared beliefs about what is appropriate or expected behavior in particular situations. For example, many cultures have highly specific norms regarding who sits where during a social gathering, who sits down first, and who passes through a door first. In every culture, some situations involve very clear norms. In the United States, court proceedings and religious services are examples of such situations. These are known as strong situations, because norms strongly influence and constrain behavioral options (Mischel, 1977). In contrast, weak situations involve norms that are less clear or strict, so that almost anything goes. In the United States, hanging around with your friends would be an example of a relatively weak situation.

Morals are beliefs about what good and bad behavior is. Three basic moral domains, abbreviated as CAD, have been proposed (Shweder et al., 1997). Community morals concern social role obligations, respect for authority, and loyalty to the group. Autonomy morals concern harming other individuals or infringing on their rights and freedoms. Divinity morals pertain to what is considered sacred and pure in the culture. Transgressions against each of these morals are associated with distinct emotions: Violations of community morals usually evoke feelings of contempt; violations of autonomy morals evoke anger; and violations of divinity morals evoke disgust (Rozin et al., 1999).

All cultures specify community, autonomy, and divinity morals but vary in the extent to which they emphasize each moral domain. A culture that places high value on conformity (e.g., China) is likely to emphasize morals concerning community; a culture that values self-

Jonathan Haidt and colleagues (e.g., Haidt & Kesebir, 2010) more recently developed moral foundations theory by expanding Shweder’s CAD to five basic moral domains: harm/care and fairness/reciprocity (based on autonomy); in-

56

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

Food for Body, Mind, and Soul

One of the ways that culture influences you in your everyday life is the food you eat. Think about what you have eaten so far today. How would the food you eat be different if you had grown up in Chicago, Berlin, Tokyo, Marrakech, or Chang Mai? Not only do cultural adaptations dictate how we obtain sustenance but all cultures have particular ways of preparing and serving foods that embody their unique identity as groups and help to define the social environment. Whether it’s hot dogs in the United States, schnitzel in Germany, sushi in Japan, tagines in Morocco, or panang curry in Thailand—

Cultures also specify ritualistic ways in which meals are to be consumed. This includes prayers (“Thank you, Lord, for this food we are about to share”) and other utterances that precede meals (“Bon appetit!”), utensils that should be used (forks, chopsticks, fingers), rules for exactly how the utensils should be held, and customs for the order in which different courses are served. If you have ever watched the culinary explorer Anthony Bourdain on television, perhaps you’ve caught a glimpse of some of the food customs of far-

The echoes of cultural adaptation on how we eat don’t stop at the social environment; they extend to the metaphysical. The physical necessity of eating is transformed into an event of not just social significance (e.g., the business lunch) but also spiritual significance, whether it is the Jewish Seder, the wedding rehearsal dinner, or the Irish wake. Further, all cultures imbue life-

Finally, because we associate food with different cultures, we can realize our desire to adapt to or affiliate with a culture by embracing the food customs we associate with that culture. So if you emigrated from China to the United States and you want to become acculturated quickly, you’ll not only start learning the language and adopting the clothing styles but you also will start eating what seems like American food. The problem, from a health point of view, is that you might also begin gaining too much weight, because American food is typically high in fat and sugar. In one clever study, when Asian American college students were told by an experimenter that they didn’t look American, they were more likely to choose American food for their lunch. The meal they chose had 182 calories more than the meal chosen by Asian American participants whose identity as Americans was not called into question (Guendelman et al., 2011). People use the food they eat to signal to themselves and others their cultural identity.

FIGURE 2.7

Ornamentation

All cultures share certain elements but put a distinctive mark on them. For example, people in virtually every culture use jewelry, tattooing, and other techniques to adorn their bodies and advertise their status. The particular style of ornamentation, however, differs greatly from culture to culture.

Customs are specific patterns or styles of dress, speech, and behavior that, within a given culture, are deemed appropriate in particular contexts (FIGURE 2.7). For example, in the United States, it is customary to clap after watching actors perform an enjoyable play; in Japan it is customary to burp after an enjoyable meal. In Navajo culture, the first person who sees a baby smile, which typically doesn’t happen until about six weeks after birth, is expected to throw a party to celebrate it. It is interesting that people are just as likely to try to avoid that honor as to try to be the lucky host: customs are widely followed, but not always happily.

FIGURE 2.8

Rituals

Universities and colleges around the world hold a commencement ceremony—

All cultures have social roles, positions within a group that entail specific ways of acting and dividing labor, responsibility, and resources. The enactor of the role is someone who has met the culture’s requirements for taking on that role and has implicitly or explicitly agreed to do so. He or she usually communicates that role through certain forms of conduct, appearance, and demeanor that are recognized by other group members. Some roles, such as those defined by gender, can inform the person’s thought and action across a very wide range of situations. Other roles, such as orchestra conductor, dictate how a person acts in a particular situation. Roles help define the self-

Cultural symbols represent either the culture as a whole or beliefs or values prevalent in the culture. In cultures where members share a nationality, flags are often used to symbolize the culture’s meaning, history, and values. Cultures defined around religious beliefs often create and recognize sacred symbols and artifacts, such as crucifixes and masks. Because symbols are seen as embodiments of cherished beliefs, ideals, and other aspects of cultural identity, they often are treated with great care, and in some cases only by select individuals. As a demonstration, try seeing if you can borrow the original U.S. Constitution for the weekend.

Cultural symbols are central aspects of a culture’s rituals, which are patterns of actions performed in particular contexts that reinforce cultural beliefs, values, and morals, and that often signal a change associated with the end of or beginning of something of biological, historical, or cultural significance (e.g., birth, puberty, marriage, the founding of one’s nation, annual holidays). Funerals, weddings, tea ceremonies, puberty-

57

Culture as Creative Adaptation

Culture provides a uniquely advantageous means for adapting to environmental change. Cultural innovations can accumulate far more rapidly than genetic mutations, and good ideas can spread horizontally across populations as well as vertically between generations. This strategy of cultural adaptation, more than anything else, has enabled our species to transform itself from a relatively insignificant large African mammal to the dominant life form on Earth.

— Richard Klein, The Dawn of Human Culture (2002, p. 26).

58

Culture is a creative adaptation that a group develops to serve its needs and desires in its particular environment. According to the anthropologist Weston La Barre (1954), cultural evolution can occur quickly, as a group develops new technologies and revises belief systems to provide flexible adaptation in meeting the demands of a changing environment. Through such cultural evolution, people can avoid getting locked into specific environmental niches. This capacity is the reason humans can be found almost everywhere on our planet and, over the last few decades, even in outer space and on the moon. Indeed, cultures can change within a single generation and sometimes almost virtually overnight. Just think of how much music, fashion, politics, and social norms have changed in the very few years that you’ve been alive. It seems unimaginable, but when your parents were growing up, there was no Internet! How did people back then get information and music? How did they socialize?

Cultural evolution

The process whereby cultures develop and propagate according to systems of belief or behavior that contribute to the success of a society.

Cultural Diffusion: Spreading the Word

Once a component of culture develops, it is picked up and used by others. Generally, the more adaptive it is, the more readily it spreads. The transfer of inventions, knowledge, and ideas from one culture to another, a process that the anthropologist Ralph Linton (1936) labeled cultural diffusion, is made possible by the human capacity for communication and learning, combined with the urge to explore and grow. This diffusion often occurs through friendly contact, business and trade, mass communication, and immigration, but also commonly results from conquest and colonization. For example, many aspects of Roman culture were diffused throughout Europe as the Roman empire spread its domination across Europe and beyond, often by means of extreme violence.

Cultural diffusion

The transfer of inventions, knowledge, and ideas from one culture to another.

Through cultural diffusion, a culture doesn’t have to depend solely on the ingenuity of its own members to meet the adaptive challenges of the environment; rather, it can benefit from knowledge, skills, and inventions developed by other cultures. For example, when the inhabitants of Tasmania arrived there over 20,000 years ago, they had a culture that was equivalent to that of Europe at the time in its material development. But because the Tasmanians were isolated from outside influence, by the time Europeans first visited them in the eighteenth century, European culture was far more technologically advanced (Linton, 1936). Europe’s location and sea-

Historical examples of ideas that have diffused in this manner include the belief in one deity (monotheism), knowledge that the earth revolves around the sun, and the idea that women should have equal rights with men. And the easier travel and communication became around the globe, the more quickly cultural diffusion occurred. Under such conditions, inventions are especially likely to spread rapidly, as can be seen with radio, television, computers, the Internet, and cell phones.

Of course, as this diffusion occurs, other cultures typically adapt these influences for their own purposes. When Marco Polo brought the technology for making pasta back from the Far East, the Italians developed their own forms and uses for it; those of us who enjoy Italian restaurants are glad of that. But these modifications are not always so unambiguously beneficial. The Internet has led to development of web sites devoted to things such as music and comic books in some cultures, but it has led to web sites devoted to racism and spreading terrorism in others.

An oft-

59

Cultural Transmission

How do we do it? Cultural innovation and diffusion across generations requires a specific kind of social interaction between experienced teachers and youngsters amenable to learning by formal instruction or imitation. The developmental psychologist Peter Hobson (2004) makes a strong case for the role of education as a defining feature of our species. Although other animals, especially higher primates, clearly learn a great deal by observing the behavior of others, human adults routinely engage in cultural transmission: explicit efforts to teach children knowledge and skills, largely with the help of language. And human children, regardless of the extent of their formal schooling, spend a considerable proportion of their early years as beneficiaries of direct efforts to inculcate them into the cultural universe of their compatriots.

Cultural transmission

The process whereby members of a culture learn explicitly or implicitly to imitate the beliefs and behaviors of others in that culture.

|

Culture: The Uniquely Human Adaptation |

|

Culture is a set of psychological and social elements shared by members of a group and passed from generation to generation. |

|

|---|---|

|

Elements of Culture All culture have the same basic elements, yet each culture’s version of them is unique. |

Cultural Evolution Culture enables people to flexibly and rapidly adapt their biological and psychological capacities to thrive in diverse and changing environments. This flexibility is made possible by the transmission of cultural elements among cultures and over generations within a culture. |