2.4 How Culture Helps Us Adapt

What does culture do for individuals and groups? One insightful answer comes from the social anthropologist W. Lloyd Warner (1959), who proposed that culture helps people adapt to three aspects of their environment:

The physical environment, through the development of skills and tools that help people meet their basic biological goals of survival and reproduction

The social environment, via the development of social roles, relationships, and order

The metaphysical environment, through the development of cultural worldviews that provide answers to the big questions that have concerned humans throughout time: Who am I? Where did we come from? Why are we here? What makes for a good life? What happens to us after death?

The nature of cultural adaptations to each of these environments is simultaneously affected by adaptations to each of the other environments, but for ease of presentation we will first consider cultural adaptations to each environment one at time.

Culture and the Natural Environment

Imagine what life would be like if you had to sleep outdoors and nourish and defend yourself with your bare hands, fortified by an occasional rock or stick! Yet our primate ancestors made do with this state of affairs for millions of years until the development of the first stone tools some 2 million or so years ago, followed a few hundred thousand years later by hand axes, control of fire, and basic shelters. These momentous developments marked the earliest beginnings of our history as the cultural animal. At this point, survival became increasingly dependent on learning how to do things that were first invented or discovered by others. The result of this entirely new form of adaptation—

60

Living in groups had many advantages. As group size increased, the number of protohumans available to learn from, and to teach, increased in kind, providing a richer array of knowledge. This promoted more rapid development, initially of tools and later of other aspects of culture. The expanded range of habitats brought more challenges to be solved with the increasing intellect that was emerging in our ancestors. These factors made increases in cognitive sophistication even more adaptive and provided a fertile ground for cultural knowledge to expand.

The Varieties of Ways to Adapt to the Physical Environment

Throughout human history, all cultures have developed means of meeting basic human needs, and hominid groups exploited the natural environments in which they lived to produce unique solutions to problems of survival. Groups living in areas with rich supplies of plants were especially likely to develop technologies for harvesting fruits and nuts; those in areas with large concentrations of animals developed effective means of hunting and trapping; those living near water developed techniques for fishing. In this way, the physical environment that groups inhabited shaped the sorts of technologies they developed.

Yet culturally developed adaptations are only partially determined by the character of specific environments. If the physical environment were the sole determinant of adaptation, then groups in similar environments should adapt to their surroundings in similar ways, but this is often not the case. Because of their different histories and traditions, groups that occupy the same territory often have radically different and mutually incompatible ways of extracting a living from it. A particularly tragic example can be found in Sudan. A vicious and geno-

Culture, Cognition, and Perception

How a given culture adapts to its physical surroundings has a profound and, in some cases surprising, influence on people’s basic perceptions and thought processes. For example, people from hunter-

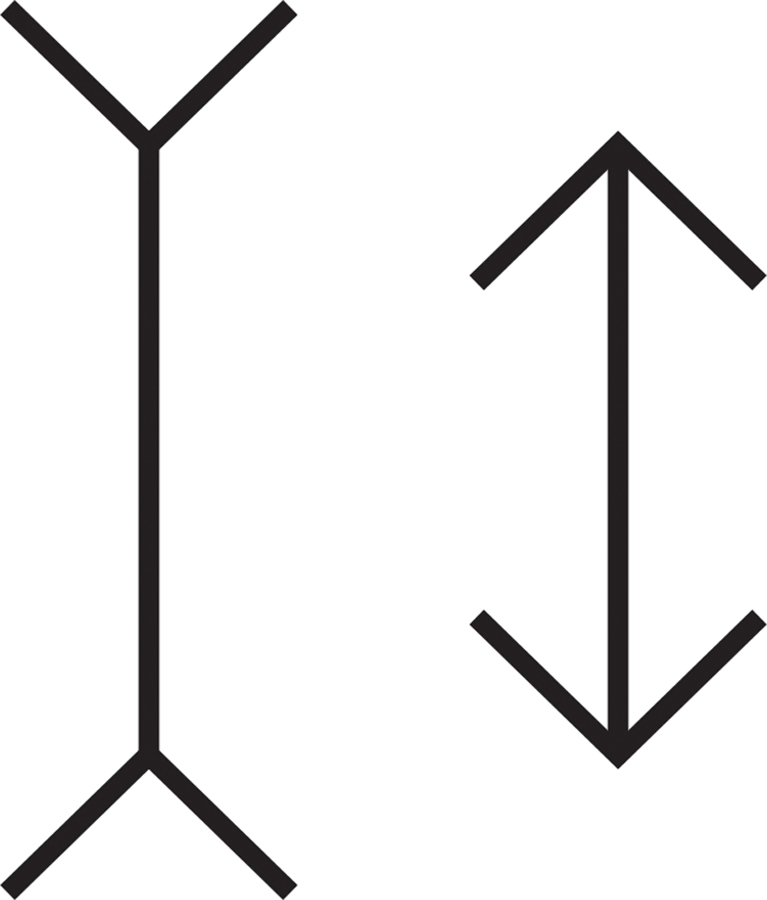

FIGURE 2.9

Müller-

Is one line longer than the other? Your ability to answer this question correctly depends on the culture in which you were raised.

Although spatial location is critical for survival in such cultures, the ability to quantify things precisely is less important. For example, although traditional Australian Aborigines do very well in spatial memory tasks, they do not do well in quantitative tasks. Indeed, when speaking their native language, traditional Aborigines generally refer to quantities greater than five simply as “many” (Dasen, 1994). In contrast, people from predominantly sedentary agricultural cultures, such as the Baoule of Cote d’Ivoire (the Ivory Coast) in West Africa, are not so skilled in visual-

61

Culture affects not only the development of cognitive skills but also susceptibility to tricks of visual perception. Consider the well-

This illusion was once considered a universal “bug” of the human perceptual system (Gregory, 1966). But cross-

Culture and the Social Environment

All groups of people, if they are to prosper, have to get along with each other, cooperate to achieve mutual goals, and minimize disruptive conflicts within the group. As societies grew in size from small bands of 100 or so people to thousands of people living in close proximity, a number of challenges of social organization arose. What were those big challenges? How do cultures differ in their solutions to them?

The Uncertainties of Group Living

One problem people in all cultures face lies in knowing what they should do and what they are allowed to do. In most modern societies, people interact on a daily basis with strangers. Because they cannot always be sure that the strangers view the world exactly as they do, they can be uncertain about what they should do in a situation, where they fit in, and how they should treat others. Consider your own awkward moments of wondering, for example, if you should call your friend’s mom by her first name.

Michael Hogg’s (2007) uncertainty identity theory explains how, to reduce this uncertainty, people identify with culturally defined groups that have clear guidelines for behavior. For example, your current author is a member of a culturally defined group of professors, and this group gives him a certain role to play. That role entails how he should act, and also how other groups (e.g., students) should act toward him. Supporting this theory are studies showing that when people are led to feel uncertain about who they are, they are more likely to identify with their cultural group, especially if that group has a clear sense of boundaries, expectations, and cohesion (Hogg et al., 2007).

How Individuals Relate to Each Other: Individualism/Collectivism

A second problem that people in all cultures face is figuring out how to orient themselves toward their relationships—

62

Community sharing, in which cooperation and self-

sacrifice are prevalent and, as in a family, “What’s mine is yours.” Authority ranking, in which one person gives orders and the other follows them, like a sergeant and a private in the army.

Equality matching, in which everyone is treated equally and has the same rights, as is typical in friendship.

Market pricing, in which relationships follow economic principles, as is typical in business relationships.

All four of these relationship patterns can be found in every known culture, but their prevalence varies considerably across cultures. The cross-

Collectivistic culture

A culture in which the emphasis is on interdependence, cooperation, and the welfare of the group over that of the individual.

More ethnically heterogeneous cultures—

Individualistic culture

A culture in which the emphasis is on individual initiative, achievement, and creativity over maintenance of social cohesion.

|

High levels of collectivism in a culture are associated with . . . |

High levels of individualism in a culture are associated with . . . |

|---|---|

|

Valuing group membership. |

Valuing independence, uniqueness, and autonomy. |

|

Valuing group harmony, even if it means silencing one’s personal views. |

General encouragement to express one’s personal views, even at the cost of disrupting social harmony. |

|

Tolerance for inconsistencies in descriptions of the self across different role contexts. |

Preference for consistency of the self across different role contexts. |

|

Fostering of an interdependent self- |

Fostering of an independent self- |

|

A clear distinction between ingroup and outgroup, coupled with a marked preference for the ingroup over the outgroup. |

A tendency to regard others as individuals, not members of groups, and to treat people the same regardless of group membership. |

|

Cognition that tends toward a holistic style that looks for relations between parts; sensitivity to connection and context. |

Cognition that tends toward an analytical style that looks for parts of the whole; sensitivity to separation and contrast. |

|

Here are a few of the many excellent papers on the extensive Implications of this cultural difference: Cross et al., 2010; Gardner et al., 2004; Markus & Kltayama, 1991; Morelll & Rothbaum, 2007; Shweder et al., 1997; Singelis et al., 1995; Suh, 2002. |

|

As the value categories displayed in Table 2.1 clearly show, both individualism and collectivism reflect core human values. Consequently, all cultures encourage some collectivistic and some individualistic tendencies. Members within cultures vary considerably in how much they embrace individualistic and collectivistic concerns. Thus, it would be inaccurate to portray members of cultures such as Japan and China as mindless automatons expressing only the collective will of the group. And it would be similarly misguided to portray members of cultures such as the United States and Great Britain as self-

63

The Nature of the Self

Hazel Markus and Shinobu Kitayama (1991) point out that in collectivist cultures, people tend to have a more interdependent self-

Interdependent self-construal

Viewing self primarily in terms of how one relates to others and contributes to the greater whole.

In contrast, people inhabiting individualistic cultures exhibit a more independent self-

Independent self-construal

Viewing self as a unique active agent serving one’s own goals.

Fitting in and Sticking out

In 2012, three members of the Russian punk-

In collectivistic cultures, behaving in a manner that fits expectations and sustains social harmony is more important than expressing one’s personal attitudes or preferences, or outperforming others. It is not that members of collectivistic cultures don’t have personal opinions; they just don’t view them as important relative to adherence to norms of appropriate behavior. In individualistic cultures, in contrast, people value freedom of speech highly and are generally encouraged to express their personal views, even if they cause debate or dissension (Gardner et al., 1999; Triandis, 1994).

Emotion

Individualistic and collectivistic cultures also differ in the way members experience and display their emotions. The collectivistic emphasis on harmony prioritizes social harmony over the freedom to broadcast one’s emotional reactions. In a study exploring this tendency (Ekman et al., 1972), American and Japanese students displayed the same negative facial expressions in response to a graphic film of a circumcision ritual when viewing it alone, but the Japanese participants inhibited such negative expressions when viewing the film in the presence of an experimenter, suggesting that individuals raised in collectivistic cultures feel less comfortable displaying their emotional reactions.

In addition to differences in emotional displays, different cultures view particular emotions as more or less desirable. For example, compared with Australians and Americans, Chinese participants judge pride to be less desirable and guilt more desirable (Eid & Diener, 2001). This fits with pride being associated with individual accomplishment, which we would expect to be a priority among members of individualistic cultures. In contrast, guilt signals a harm done to others and motivates efforts to repair the threatened relationship (Baumeister et al., 1994; Rank, 1936b; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Thus, the differential values placed on pride and guilt support the idea that collectivist cultures place greater emphasis on social obligations and maintaining social bonds. These cultural differences in emotional norms and displays have important implications, particularly when people from different cultures interact. For example, in medical contexts, differences in cultural norms for emotion might lead American doctors to view Asian patients as less excited about, and thus receptive to, medical treatment (Tsai, 2007).

64

A third psychological difference refers to how people generally draw a distinction between the ingroup and the outgroup, with members of outgroups treated very differently from fellow ingroup members. In collectivistic cultures, people are less constrained in expressing negative feelings regarding outgroup members. I ndeed, treating outgroup members differently is considered the right thing to do. In contrast, members of individualistic cultures tend to view others as individuals rather than as group members and thus try to adhere to the norm of treating people the same regardless of their group membership (Triandis, 1994).

Modernization and Cultural Values

In cities such as Miami that have fewer lifelong residents, fans are less likely to remain loyal when their team is having a losing season. The Miami Marlins, for example, have shown considerable variability in their attendance over the years.

The spectrum between individualism and collectivism is one general way to characterize a culture’s norms and values, and to understand how that value profile governs social relations and provides social order. An important factor that influences how cultures evolve to meet these needs is modernization. Over the last 500 years, there has been a general trend toward increased socioeconomic development; industrial, technological and economic advancements; and democratization. How might these changes have influenced the values that people hold?

One consequence of these changes is that we live in increasingly diverse societies because social policies allow for immigration, and technology makes it easier to travel far from home while still maintaining connections with family. Triandis (1989) proposed that as cultures become more heterogeneous, they tend to become more individualistic and less collectivistic. Consider that a recent analysis of pronoun use in American books published between 1960 and 2008 revealed a 10% decrease in the use of words such as “we” and “us” alongside a 42% increase in “I” and “me” (Twenge et al., 2013). Even the already individualistic United States might be becoming even more individualistic over time.

In cities such as Miami that have fewer lifelong residents, fans are less likely to remain loyal when their team is having a losing season. The Miami Marlins, for example, have shown considerable variability in their attendance over the years.

This rise in individualism might result from the increasing mobility that people have. Shigehiro Oishi and colleagues have argued that as people move around from place to place, forgoing their roots in a single, long-

As those within societies become more mobile, societies become increasingly diverse and tend to value that diversity as well as other progressive belief systems. Schwartz and Sagie (2000) examined socioeconomic development, cultural values, and political characteristics of 42 countries from 1988 to 1994. They found that as cultures modernized or embraced democracy, they increasingly prioritized new ideas, individual initiative, personal worth, equality, and status judgments based on achievement rather than on tradition. As socioeconomic development increased, so did the importance of the values of self-

65

Culture and the Metaphysical Environment

Happy the hare at morning, for she cannot read

The hunter’s waking thoughts, lucky the leaf

Unable to predict the fall, lucky indeed

The rampant suffering suffocating jelly

Burgeoning in pools, lapping the grits of the desert.

But what shall man do, who can whistle tunes by heart,

Knows to the bar when death shall cut him short like the cry of the shearwater,

What can he do but defend himself from his knowledge?

—W. H. Auden (1907–

In addition to helping people adapt to their physical and social environments, culture helps them to adapt to their metaphysical environment, by which we mean our understanding of the nature of reality and the significance of our lives within the cosmic order of things. But why are people the world over preoccupied with understanding their place in the metaphysical environment? To answer this question we have to recognize that humans’ sophisticated intellectual abilities are a mixed blessing. On the one hand, our ability to think symbolically about time and space is tremendously adaptive; as we’ve seen in this chapter, it allows us to imagine possibilities and communicate with each other in complex ways. But this intelligence has some problematic consequences. According to the cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker, writing in books such as The Birth and Death of Meaning (1971) and The Denial of Death (1973), the most chilling result of our species’ vast intelligence is the awareness that the only truly certain thing about life is that it will end someday. We know that death is inevitable and inescapable, and that it could come at any moment from any number of causes. Awareness of the fragility of life and the inevitability of death in an animal that seeks survival creates the potential for paralyzing terror. Becker proposed that such terror simply would be too much for a self-

In the mid-

Terror management theory

To minimize fear of mortality, humans strive to sustain faith that they are enduringly valued contributors to a meaningful world and therefore transcend their physical death.

Cultural worldview

Human-

In this way, cultural worldviews emerged that gave life meaning, order, value, and promises that life will continue in some manner beyond the point of physical death. To specify, all cultural worldviews consist of: (1) a theory of reality that provides answers to basic questions about life, death, the cosmos, and one’s place in it; (2) institutions, symbols, and rituals that reinforce components of that worldview; (3) a set of standards of value that prescribe what is good and bad, and what it means to be a good human being; and (4) the promise of actual or symbolic immortality to those who believe in the worldview and live up to the standards of value that are part of it.

66

By imposing meaning on the subjective experience of reality and creating a sense of enduring significance for the self, cultural worldviews help people maintain the belief that they are more than transient animals in a purposeless universe, fated only to die. A person can view him-

Although all cultural worldviews address basic existential concerns, they vary considerably in the specific beliefs and values they employ. In the following sections, we will consider both the similarities and the differences among cultures in the aspects of their worldviews central to terror management: creation stories, cultural institutions, symbols and rituals, bases of self-

Creation Stories

Where did we come from? How did life begin? How do we humans fit into the grand scheme of things?

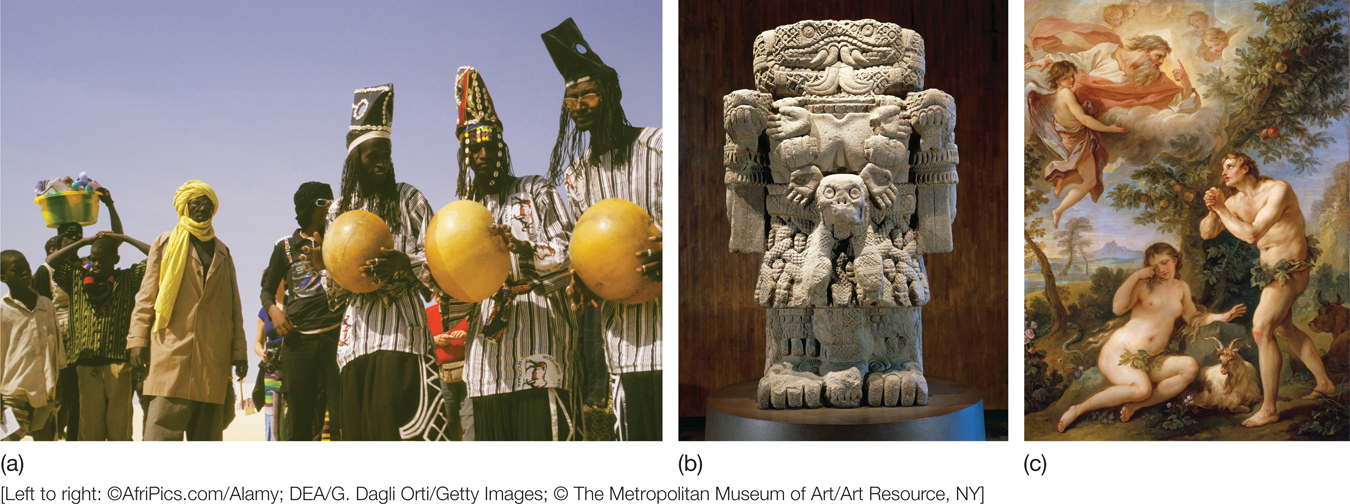

FIGURE 2.10

Creation Stories

All cultures have stories about the creation of the world and the people in it: (a) members of the Fulani tribe from West Africa; (b) figurine of Coatlicue, the Aztec goddess; (c) The Expulsion from Paradise, 1740, painting depicting the Judaeo-

In Mali in West Africa, the Fulani (FIGURE 2.10a) believe the world was created from a giant drop of milk, from which the god Doonari emerged and created stone. The stone created iron, iron created fire, fire created water, and water created air.

The Aztecs’ world was initiated when Coatlicue (FIGURE 2.10b), the Lady of the Skirt of Snakes, was created in the image of the unknown. She was impregnated by an obsidian knife and gave birth to female and male offspring who became the moon and the stars.

In the Judeo-

These examples were gleaned from David and Margaret Leeming’s (1994) Dictionary of Creation Myths. The Leemings acknowledge the tremendous variation in the details but note the common themes:

The basic creation story, then, is that of the process by which chaos becomes cosmos, no-

Questions concerning the origins of life have had great importance for humankind since the earliest days of our species and continue to fascinate. Perhaps it has occurred to you that the big bang theory of the origin of the universe and the theory of evolution by natural selection are contemporary examples of creation stories.

67

Institutions, Symbols, and Rituals: Worldview Transmission and Maintenance

Cultural worldviews must be transmitted from generation to generation and must be continually reinforced so people can sustain faith in them and avoid the realization that they are essentially fictional accounts of reality. For example, in the United States, the elaborate public education system teaches children the history of the United States in terms of names, events, and dates. But it also teaches mythical stories, such as the honesty of George Washington and the steadfastness of Betsy Ross in sewing the first American flag. Similar names, events, and dates might be taught in another culture, but the tone of those lessons might be quite different, conveying that particular culture’s current view of those historical people and events. For example, although Americans view the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor as an unjustified, egregious sneak attack, the Japanese view it quite differently. In the context of their worldview, the United States had acted aggressively toward Japan by imposing an embargo that threatened its national security. The embargo blocked Japan’s access to the South Pacific’s oil and natural resources, which were critical to the survival of the Japanese way of life.

Similarly, in a culture’s primary language classes, children learn the cherished poems, stories, and novels of that culture, and the cultural morals and values they convey. Science classes convey certain attitudes and values regarding the environment, animals, other people, and appropriate goals toward which the society should strive. In addition, churches, mosques, and synagogues teach the religious aspects of the worldview. These aspects of the culture are further reinforced throughout people’s lives by a wide variety of clubs and organizations, such as the Girl Scouts and the Lions Club; and by many rituals, such as first communions, bar mitzvahs, weddings, and funerals; and even by playing the Star Spangled Banner before major sporting events (e.g., Super Bowl).

Think ABOUT

68

Holidays celebrating culturally significant events and values, such as Independence Day, Cinco de Mayo and Eid al Fitr (the end of Ramadan) also play a key role in maintaining faith in the dominant cultural worldview. And of course, people in every culture are surrounded by cherished symbols of their cultural beliefs, including totem poles, flags, murals, coins, or artwork. What are some of your own cherished cultural symbols?

Bases of Self-worth: Standards, Values, Social Roles, and Self-esteem

Beyond providing and maintaining a meaningful explanation of reality, all cultures give their members standards of value, specifying which personal characteristics and behaviors are good and which are bad. Living up to these cultural standards of value provides a sense of self-

All cultures provide a wide range of benefits to those who meet or exceed the cultural standards of value, for example, money, better health care, awards and prizes, and good mating prospects. These benefits contribute to individuals’ hope that they will continue, in some way, beyond physical death. Reinforcing the connection between goodness and good outcomes, all cultural worldviews convey that good things will happen to the worthy and bad things will happen to the unworthy. Melvin Lerner labeled these ideas just world beliefs and, with colleagues, has shown that people are highly motivated to maintain faith in such beliefs (e.g., Lerner & Simmons, 1966). For example, people look for ways to believe that victims of misfortune must have done something to deserve their fates (Hafer & Bégue, 2005).

Self-esteem

A person’s evaluation of his of her value or self-

Just world beliefs

The idea that good things will happen to the worthy and bad things will happen to the unworthy.

Although the need for self-

A heroic accomplishment for a Crow Indian warrior is to gallop into an enemy camp and touch one enemy warrior without injuring him.

Tlingit Indians are valued in proportion to how many blankets and other objects they have accumulated and then either given away or destroyed.

Status Symbols. Standards for self-

We would add to this list:

American men are highly valued if they can hit a spherical object with a wooden stick effectively 3 out of every 10 times that such an object is hurled at them.

Standards for obtaining self-

Striving for Immortality

Recognizing the inevitability of death is a terrifying prospect for an animal that shares with all life forms a basic biological imperative to survive. A cultural worldview provides a theory of reality and standards through which individuals can attain self-

Literal immortality

A culturally shared belief that there is some form of life after death for those who are worthy.

Symbolic immortality

A culturally shared belief that, by being part of something greater and more enduring than our individual selves, some part of us will live on after we die.

69

Even a passing glance at past and current cultures the world over reveals that the hope of literal immortality has been central to most cultures and organized religions. Archeological excavations reveal that elaborate ritual burials begin abruptly and appear regularly with the emergence of modern humans, suggesting that concerns about death have been with us from the earliest days of our species (Mithen, 1996; Tattersall, 1998). Indeed, the oldest known written story—

Virtually all major contemporary religions promise some form of afterlife. Recent surveys suggest that most people around the world believe in some form of afterlife: 51% say yes, 26% say probably but not certain, 23% say no. Confidence in the afterlife is even higher in the United States: 69% say absolutely yes, and only 11% say that you simply cease to exist after death (Ipsos/Reuters, 2011).

Consider different cultures’ contemporary conceptions of the afterlife (Panati, 1996). Many Jews believe that the righteous are resurrected in Olam Ha-

In addition to the prospect of literal immortality, cultures can offer routes to symbolic immortality. In symbolic immortality, humans transcend death by being part of, or by contributing something to, an entity greater than the self that will continue after physical death. The psychohistorian Robert Jay Lifton (1979) proposed that cultures provide (in varying degrees) four different modes of symbolic immortality: biosocial, creative, natural, and experiential. Research supports the idea that the more people have a sense of symbolic immortality, the less afraid they are of death (Florian & Mikulincer, 1998).

One way to feel immortal is to have children, because your genes as well as your lasting influence will live on in them for future generations. Jim Bob and Michelle Duggar have 19 kids.

Biosocial immortality is obtained by having children and identifying with larger collectives such as nations. Some aspect of parents will live on through their children and their children’s children and so on in perpetuity; nations are presumed to continue indefinitely.

Creative immortality results from contributions to one’s culture. Examples include heroic acts or noteworthy leadership, helping others by using one’s knowledge and skills for the betterment of humankind and passing them on, and highly regarded scientific and artistic accomplishments.

According to Abraham Maslow, peak experiences can allow us to transcend our mortal selves.

Natural immortality results from strongly identifying with nature—

Finally, experiential immortality results from “peak experiences,” described by Abraham Maslow (1964) as quasi-

70

These various forms of immortality are found in all cultures. The fact that these elements of culture are universal suggests that they reflect a basic human desire to minimize the terror of mortality by feeling transcendent over death. The fact that cultures vary so much in how they explain the origins of life; their institutions, symbols, and rituals; what makes for a good and valuable life; and what happens after death is a testament to human creativity. It shows that, although probably not just any set of beliefs and values will do, there are many ways to fulfill this desire.

The Essential Role of Social Validation

TMT proposes that people protect themselves from the uniquely human fear of death by immersing themselves in the world of symbols and ideas provided by their culture. This might seem a rather flimsy defense against the biological reality of death. In a sense, it is flimsy. But people work very hard to sustain unwavering faith in the absolute validity of their cultural worldview and their sense of self-

Confidence in the absolute correctness of our own beliefs and values, and of our own value, is bolstered primarily through social consensus and social validation. The idea that people rely on others to help them verify the validity of their own perceptions and beliefs has a long history in social psychology that we briefly touched on in chapter 1. According to Festinger’s social comparison theory (1954), people constantly compare themselves, their performance, and their attitudes with those of others around them. When other people share the same beliefs or values, it implies that those beliefs and values are correct; when other people hold different beliefs and values, it raises the possibility that someone is mistaken. When cultures collide, worldviews are threatened.

The Threat of Other Cultures: A Root Cause of Prejudice

As we have seen, cultures vary greatly in their beliefs about human origins, bases of self-

Empirical Tests of TMT

Research to assess TMT has focused primarily on cultural worldviews and self-

Mortality salience

The state of being reminded of one’s mortality.

Worldview defense

The tendency to derogate those who violate important cultural ideals and to venerate those who uphold them.

71

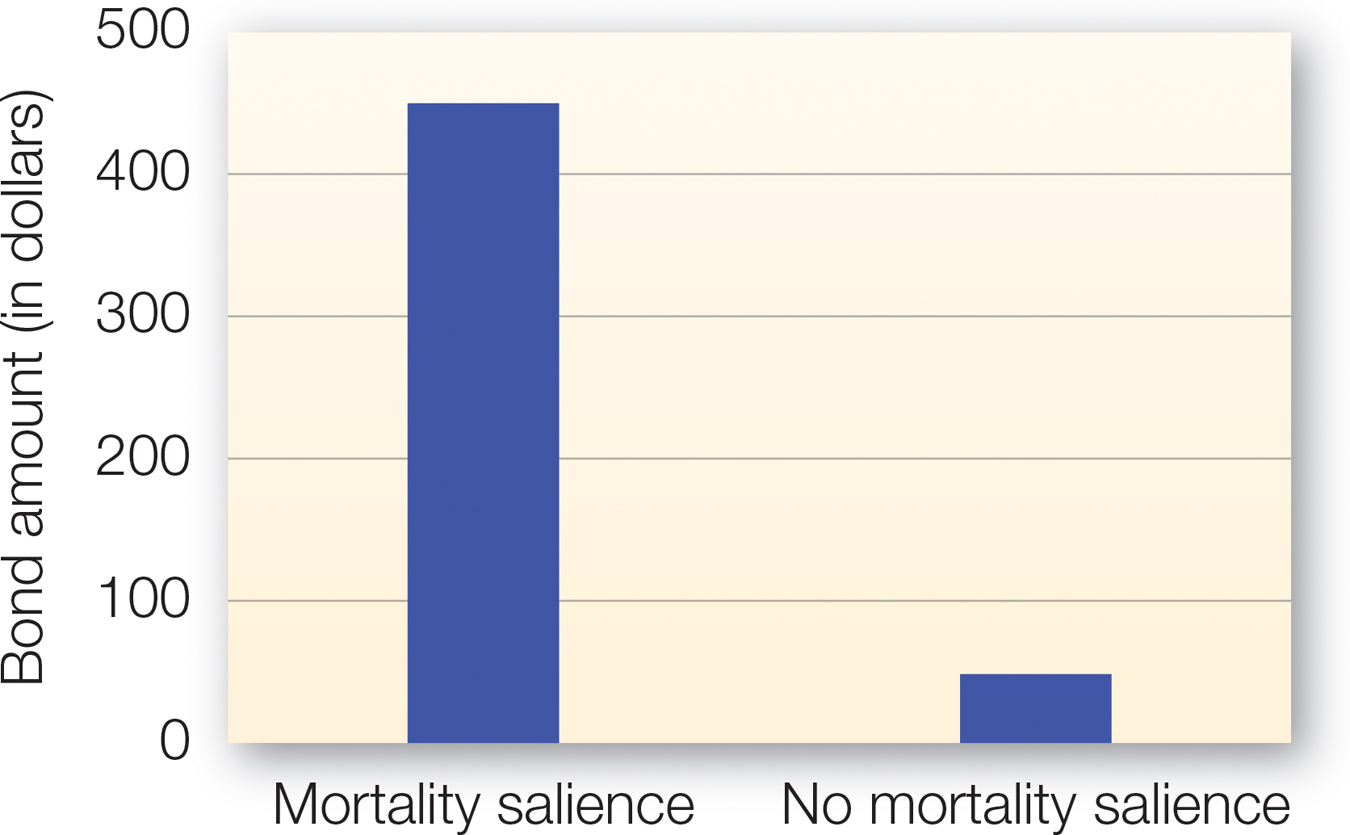

FIGURE 2.11

Worldview Defense after Mortality Reminders

According to terror management theory, cultural worldviews protect people against mortality fears. Consequently, people primed to think about their deaths—

[Data source: Rosenblatt et al. (1989)]

Punishing Villains and Rewarding Heroes

In the initial test of the mortality salience hypothesis (Rosenblatt et al., 1989), municipal court judges were told they were participating in a study examining the relationship among personality traits, attitudes, and bond decisions. (A bond is a sum of money that a defendant must pay after arrest to be released from prison prior to the trial date.) Embedded in the questionnaire packets for half of the judges, who were chosen by random assignment, was a “new personality assessment” that asked for short responses to the following questions: “Please briefly describe the emotions that the thought of your own death arouses in you,” and “Jot down, as specifically as you can, what you think will happen to you as you physically die and once you are physically dead.” The other judges were the control group and did not receive this questionnaire.

All of the judges were then presented with a hypothetical legal case brief that provided information about the defendant, who was charged with prostitution, and the circumstances of her arrest. The information was followed by a form asking the judges to set bond for the defendant. Because prostitution violates a moral stance in the judges’ worldviews, the hypothesis was that reminders of mortality would motivate the judges to uphold their worldview by being especially punitive toward the prostitute, in the form of setting an especially high bond. As shown in FIGURE 2.11, the results supported this hypothesis. This is a shockingly large difference, given that all judges reviewed exactly the same materials, except for the presence or absence of the mortality reminder.

Many follow-

The Safety of a National Identity

Research has also examined how thoughts of death affect reactions to people and ideas that more directly support or challenge one’s worldview. For example, when reminded of death (vs. a control topic), American participants gave especially positive evaluations to essays and authors that praised America and especially negative evaluations to those that were critical of America. Presumably, being reminded of death increased participants’ need for faith in their American worldview and as a result, they were especially attracted to people who helped them view their nation in a positive light and especially repulsed by those whose comments conflicted with such a rosy view. Studies conducted in other countries similarly show that mortality salience intensifies nationalistic bias. For example, Germans interviewed at a cemetery expressed a greater preference for German culture over other European cultures in terms of features such as travel destinations, cars, and cuisine compared with those interviewed away from a cemetery (Jonas et al., 2005). And after a reminder of mortality, people are especially reluctant to treat cultural symbols such as flags and crosses inappropriately (Greenberg et al., 1995).

72

The Protective Shield of Cultural Beliefs

The studies on villains and heroes, national identities, and cultural symbols showcase just a few of the ways that reminders of mortality influence people’s judgment and behavior. When particularly aware of their mortality, people cling more tenaciously to that which supports their cultural worldview. This provides protection from thoughts of death. So what might happen when these cultural beliefs are compromised or one’s faith in their validity is undermined? If you’ve been following the logic of TMT, you might suspect that when cultural beliefs are undermined—

Many studies have supported this idea (Hayes et al., 2010). The typical study has an individual read a criticism of her worldview and then asks her to complete a series of word stems such as coff_ _. Reading a criticism of their worldview makes it more likely that people will complete such word stems with “coffin” instead of the more common “coffee.” The more death-

Consider one particularly chilling example of this process (Hayes et al., 2008). When Christian participants read about how Muslims are gaining dominance in Nazareth, the childhood home of Jesus Christ, thoughts of death became more accessible. But when participants were later exposed to a news story describing how a plane full of Muslims had crashed and all aboard had died, thoughts of mortality were no longer close to awareness (Hayes et al., 2008). This study thus illustrates not only how threats to one’s culture can “unleash the beast of mortality awareness,” but that this beast can be recaged through the annihilation of the worldview threat.

Is Death the Factor Responsible for These Findings?

Such findings are also important because they help to highlight the direct connection between awareness of death and cultural beliefs. Not only do reminders of death increase investment in culture, but threatening that culture increases awareness of death. Of course, death is not the only psychological threat that leads, for example, to more extreme reactions to those who are different. Other threats can and indeed do produce important psychological responses. We have touched on some of these already, such as the threat of uncertainty (Hogg, 2007), and we will discuss others in later chapters. At the same time, thoughts of death do produce unique effects in human judgments and decisions that are not produced by other unpleasant, uncertain, or anxiety-

Culture as a Synthesis of Human-Created Adaptations

Table 2.3 lists the three human environments we have discussed and summarizes how culture helps people to adapt to each of them. However, it is important to recognize that each of these domains of cultural adaptation simultaneously influences, and is influenced by, adaptations to the other two domains.

|

Environments |

Human Adaptations |

|---|---|

|

The Physical Environment: How do people in groups manage the physical environments in which they live? |

Technology (skills and tools). |

|

The Social Environment: How do people in large groups of (mostly) strangers get along with each other? |

Shared beliefs systems (e.g., norms, roles, and interaction customs) that reduce uncertainty about the self and one’s actions; orient the self toward relationships with others; and establish and maintain social order. |

|

The Metaphysical Environment: How do people in groups manage the awareness of threatening realities inherent to our existence, most notably the fact that it ends in death? |

Faith in a meaning- |

For example, the demands of the physical environment, such as how specific groups extract a living from it, greatly influence a culture’s social environment, such as roles and norms. Hunting cultures are generally more individualistic, because hunting is a relatively individual activity. In contrast, agricultural cultures are generally collectivistic because large-

73

To appreciate more fully how a synthesis of adaptations to the physical, social, and metaphysical environments determines the character of a culture, let’s look at culture’s influence on people’s thinking styles.

The physical, social, and metaphysical worlds interact to influence some basic aspects of thinking. The most widely studied broad cultural difference in style of thinking about the world concerns East Asian versus Western cultures. In his book Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently—

Nisbett argues that these differences reflect very different metaphysical traditions of philosophical thought that emerged in ancient China, a great influence in the Far East, and ancient Greece, a central influence on Western culture. Ancient China was a relatively ethnically homogeneous, large culture that gave rise to the philosophies of Taoism and Confucianism, which in turn led to a focus on the yin and yang, multiple sides to truth and life, balance, social cohesion and obligation, and harmony with nature. This Chinese tradition encouraged social practices that promoted holistic thinking, which focuses on overall context and relations among contiguous elements. This type of thinking then reinforced a collectivistic worldview and its associated social practices, as we discussed earlier in this chapter.

Ancient Greece, in contrast, was composed of small, contentious city-

Although Nisbett’s historical analyses of the genesis of East-

74

One more example might help to illustrate further the cultural difference between holistic and analytical thinking. Holistic thinking involves seeing multiple sides to an issue and sustaining contradictions, known as dialectical thinking, whereas analytic thinking involves choosing one view over another. To assess this difference, Chinese and American graduate students were asked to read and analyze stories about conflicts between people (Peng & Nisbett, 1999). The Chinese students tended to attribute the cause of the conflict to both individuals and emphasize the need for compromise—

|

How Culture Helps Us Adapt |

|

Culture simultaneously helps people adapt to the physical, social, and metaphysical environment in which they live. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Culture and the Physical Environment Human adaptation to the natural environment was facilitated by technological innovations and group living, which encouraged more flexible means of solving problems. In a given culture, adaptation to the physical environment takes particular forms, depending on the challenges of local environments and the unique needs and values of the groups that occupy them. |

||

|

Culture and the Social Environment People in every culture must adapt to their social environment in terms of: Uncertainty about what one can and should do. Orienting the self toward one’s relationships and personal goals. Cultures differ in how they solve these problems. Cultures provide clearly defined roles and norms. Collectivistic cultures emphasize cooperation and group welfare. Individualistic cultures emphasize values such as individual achievement. This distinction has implications for how people conceptualize themselves, experience and display emotions, and form attitudes about out group members. Modernization has a range of consequences that determine which values are most important to members of a culture. |

||

|

Culture and the Metaphysical Environment Cultural worldviews help people understand why they are alive, what they should be doing while they are alive, and what will happen to them once they are dead. Both faith in the cultural worldview and the maintenance of self- Tests of terror management theory support the hypothesis that reminding people of their mortality increases protection of their worldviews, and that undermining the worldview increases thoughts about death. |

||

|

Culture as a Synthesis of Human- Humans adapt to each of the three environments simultaneously because each is heavily influenced by adaptations in the other two domains. Cultures can be defined as either holistic or analytical on the basis of different metaphysical traditions. Many aspects of a given culture reflect its adaptation to all three environments. |

||

75