2.5 Culture in the Round: Central Issues

There is no domain of human thought or activity that is not influenced by a culture’s particular rich synthesis of adaptation to the physical, social, and metaphysical world. To conclude this chapter, we consider some important, broad questions about culture.

Does Culture Illuminate or Obscure Reality?

Culture is a uniquely human form of adaptation. Some theorists (Harris, 1979/2010) view it as a body of knowledge that developed to provide accurate information to people that helps them adjust to the many demands of life, whether that means obtaining food and shelter, defending against rival outgroups, and so on. Culture also tells us how groups of people work together to achieve mutually beneficial goals, and how to live our lives so that others will like and accept us—

However, adaptation to the metaphysical environment suggests that people do not live by truth and accuracy alone. Sometimes it is more adaptive for cultural worldviews to distort the truth about life and our role in it. Some things about life are too emotionally devastating to face head on, such as the inevitability of death. Because overwhelming fear can get in the way of many types of adaptive action, it sometimes is adaptive for cultures to provide “rose-

Is Culture a Good or Bad Thing?

Culture is a necessary part of being human. Building on generations of accumulated wisdom and innovation culled from many cultural influences, our own culture helps us enjoy our lives, answer our toughest questions, and keep our deepest fears at bay. It provides tried and true forms of cuisine, entertainment, and technology. It gives us ways to feel connected, protected, and valuable. A human lacking or stripped of culture would be psychologically (and probably physically) naked, fearful, hard pressed to survive, and barely recognizable as a member of our species.

Cultures other than one’s own are important as well, because through cultural diffusion, cultures share innovations that mutually enhance people’s lives, offering them novel cuisines, technologies, music, and art. Imagine if you visited Oslo, Prague, Rio, or Beijing and all you found was strip malls full of the same fast-

Although we can’t go about stripping an individual of his or her culture in a laboratory experiment to assess these functions of culture directly, anthropologists and psychologists have detailed many tragic historical examples of cultural disruptions, some of which have led to complete cultural disintegration. The documented effects of these cultural traumas seem to provide clear evidence of the psychological importance of culture.

Cultural traumas

Tragic historical examples of cultural disruptions, some of which have led to complete cultural disintegration.

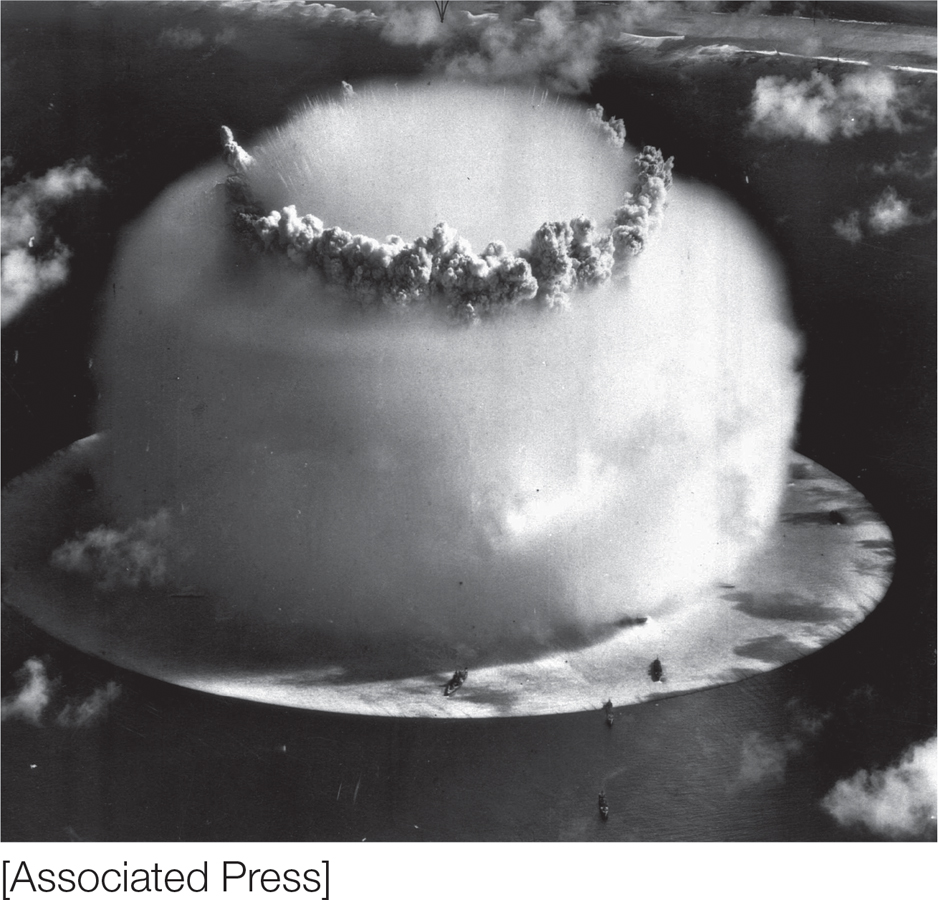

FIGURE 2.12

Cultural Trauma

Culture makes us human, providing us with a basis for making meaningful sense of our lives and feeling valuable. Forcibly stripping a group of their cultural heritage—

A dramatic and sudden example of cultural trauma befell the inhabitants of Bikini Island in the South Pacific. The Bikinians were removed from the island by the U.S. government, which used the island to conduct 67 nuclear tests between 1945 and 1958 (FIGURE 2.12). The result was severe demoralization and stress among the Bikinian people, problems with which their descendants are still coping today. In a similar finding, research on children displaced by war or natural disaster consistently shows that those children whose cultural base has been disrupted by traumatic events are likely to develop posttraumatic stress disorder, whereas those who retain a strong cultural base cope much better (Beauvais, 2000).

76

Over the course of history, cultural traumas have been experienced by indigenous tribal cultures throughout the world, as their ways of life and belief systems have been abruptly or gradually altered, and sometimes completely undermined, by intrusions from more technologically advanced cultures. The best-

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

Black Robe

Black Robe

Black Robe, directed by Bruce Beresford (Eberts et al., 1991) with the help of Native American consultants, is a fictionalized but realistic account of historical events. In the 1600s, Jesuit priests traveled from France to what is now Québec to help convert the Huron tribe to Christianity. Algonquin tribe members are given gifts such as metal tools in exchange for helping Father LaForgue and his assistant Daniel reach the Huron mission. The film emphasizes both the commonalities and the differences between the French and Algonquin cultures.

Early in the movie, we see the Algonquin chief, Chomina, and Samuel de Champlain, the leader of the French, getting dressed in garb that connotes their high status. Every culture uses clothes and ornaments for this purpose. Both the French and Algonquin play music and dance. They both ingest consciousness-

We also see what seem, from outside each culture’s respective worldview, very strange behaviors. La Forgue self-

The cultures are different in two principal ways. First, the French culture is more individualistic, the Algonquin more collectivistic. The Algonquin share everything without question and have no sense of private property (communal sharing). They also obey Chomina and the other tribal elders (authority ranking). The French are oriented more toward market pricing, wanting to trade tobacco for other things rather than sharing it. And there is more of a sense of equality matching between LaForgue and Daniel. Daniel has no problem disobeying La Forgue and at one point is willing to abandon him to be with Annuka and the Algonquin. Annuka has no thought of ever abandoning her tribe.

Second, French culture is more technologically advanced, an advantage that helped many European nations colonize indigenous tribal cultures. La Forgue eventually reaches the Huron mission and finds the Huron plagued by a deadly disease and desperate. He converts them and holds a large-

On the other hand, even cultures that are working well for their members have their negative side. Each culture limits the way its people think about themselves and the world and creates divides between its people and others within and outside the culture. We humans have great potential for freedom of thought and choice because of our reduced reliance on instinctual patterns of behavior and our flexible intelligence. But culture imposes preferred beliefs, attitudes, values, norms, morals, customs, and rituals on us, often leading us to internalize these worldviews long before we have the cognitive or physical capabilities or independence to question them or develop and institute alternative ways of thinking and behaving. Indeed, Becker (1971) argued that each culture is like a shared neurosis, a particular, peculiar, and limited way of viewing the world and acting in it. Consequently, those outside the culture are likely to view the behavior of those within it as odd, if not outright crazy.

77

Think ABOUT

Culture affects how people treat those of lower status within the culture as well as those outside the culture. This has contributed greatly to social problems within cultures and egregious conflicts between cultures, often leading to the tragic cultural traumas we have already noted. This aspect of culture is what makes James Joyce’s (1961, pp. 22-

All these very real negatives notwithstanding, culture is with us and in us and always will be, at least in some form. As we proceed through this textbook, we will continually consider the specific ways cultures contribute both positively and negatively to human functioning.

We will leave it to you to ponder whether some cultures and aspects of culture provide a better ratio of benefits to costs than others.

78

Is There Just One Culture? Beyond a Monolithic View

For presentational purposes in this chapter, we have generally treated culture as a single, largely static entity. However, as we noted at the outset of this chapter, cultures actually are continually evolving. In addition, cultures are often very heterogeneous, consisting of many subcultures. It is important to recognize that members of such subcultures are profoundly influenced by both their subculture and its relationship to the dominant culture.

The tone of this chapter could be taken to suggest that because people are deeply embedded in their cultures, they are mere helpless pawns of their cultural upbringing. But clearly within cultures, people vary greatly in their traits, beliefs, values, preferences, and behaviors. So how much of the person is determined by his or her culture as opposed to universal or unique characteristics? Although there is no basis for putting a number on how much, one way to examine this issue is to consider research on immigrants, people who move from one culture to another. How much do they keep? How much do they change? How easily can they adapt to the norms and customs of a very different culture? Fortunately, there is a body of theory and research on acculturation—the process whereby individuals change in response to exposure to a new culture—

Acculturation

The process whereby individuals adapt their behavior in response to exposure to a new culture.

Refugees from war-

One of our wives has worked with the International Rescue Committee (IRC) to help refugees allowed into the United States to settle into life in America; she found this to be an incredibly eye-

Imagine the adjustment to American culture! One caseworker found a group of Somali women sitting in a modern American apartment in a circle on the kitchen floor, cleaning chicken together. This is very odd when seen through American eyes—

Systematic research confirms that, although some level of acculturative stress is not uncommon, most immigrants succeed in growing accustomed to their new culture (Berry, 2006; Furnham & Bochner, 1986). Some people gradually shift almost entirely from their traditional culture to the beliefs and ways of the new culture, a process known as assimilation. As people assimilate, they not only embrace the new culture’s ways of dressing, eating, and so on but also begin thinking in ways promoted by the new culture (Berry, 1997; Church, 1982; Kitayama & Markus, 2000).

Assimilation

The process whereby people gradually shift almost entirely from their former culture to the beliefs and ways of the new culture.

Most immigrants retain aspects of their former culture while adapting to the new culture, a process known as integration. Immigrants who have achieved integration are referred to as bicultural because they identify with two cultures simultaneously. It is interesting to note that research on bicultural individuals suggests that they can think and act like members of either culture, depending on which culture’s language they are using or which culture’s symbols are prominent in their minds. Consider a study set in Hong Kong (Hong et al., 1997), a city of people primarily of Chinese descent and under Chinese control since 1997, but heavily influenced by Western culture because of 100 prior years of British rule. Researchers showed participants a cartoon of one fish swimming in front of a group of other fish. If shown pictures of a cowboy and Mickey Mouse first, they explained the lead fish’s behavior in terms of the characteristics of the fish, much as Westerners typically do. However, if first shown pictures of a Chinese dragon and temple, they explained the fish’s behavior in terms of the situation the fish was in, as Easterners typically do. This phenomenon further attests to the ability of people to transcend the perspective of one particular cultural worldview and shift to another when exposed to that worldview as well.

Integration

The process whereby people retain aspects of their former culture while internalizing aspects of a new host culture.

79

Whether individuals with a background in one culture but living in another ends up assimilating, integrating, or becoming marginalized depends in part on their own choices, the strength of their initial cultural identification, and the compatibility of the two cultures. But it also depends on the attitude of the current culture toward immigrants and those with sub-

Melting pot

An ideological view holding that diverse peoples within a society should converge toward the mainstream culture.

Multiculturalism (cultural pluralism)

An ideological view holding that cultural diversity is valued and that diverse peoples within a society should retain aspects of their traditional culture while adapting to the host culture.

In historical terms, American culture could be characterized as having generally had a melting pot orientation with regard to European immigrants, while simultaneously having a discriminatory orientation, fostering marginalization, with regard to African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanic Americans. Currently, the cultural diversity movement, which primarily targets societal orientations toward blacks, Native Americans, and Hispanics, is attempting to move American culture toward a multicultural orientation. If it succeeds, it may eventually help shift members of these groups from marginalization to integration (Moghaddam, 1988).

|

Culture in the Round: Central Issues |

|

Social psychologists consider broad issues about culture. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cultures strike a balance between human needs for accurate information and for comforting beliefs that often obscure reality. |

Culture serves many vital functions that promote happiness and well- |

Culture is not a single, blanket entity but contains important subcultural differences and influences. |

People coming to a new culture can struggle, but they can assimilate to and integrate aspects of the new culture. |

CONNECT ONLINE:

Check out our videos and additional resources located at: www.macmillanhighered.com/