3.2 The “How” of Social Cognition: Two Ways to Think About the Social World

As we humans evolved, we developed neocortical structures in the brain that allow for high-

Cognitive system

A conscious, rational, and controlled system of thinking.

Experiential system

An unconscious, intuitive, and automatic system of thinking.

85

The Strange Case of Facilitated Communication

Although it initially seemed to provide severely autistic children with a method for communicating with others, facilitated communication was eventually discredited after it was discovered that the adult facilitators were unconsciously shaping the messages that the children typed out.

[© Krista Kennell/Corbis]

In the fall of 1991, Mark and Laura Storch were informed that their 14-

Facilitated communication quickly aroused skepticism, however, as children such as Jenny began sharing horrific stories of sexual abuse (Gorman, 1999). When the scientific community investigated the technique, study after study suggested that the thoughts being typed out were not those of the autistic child, but rather were those of the facilitator. In one experiment, two autistic middle schoolers were shown pictures of common objects and asked to type out what they saw (Vázquez, 1994). The experimenter could not see the pictures on the cards, and in half the trials, the facilitator was also prevented from seeing the cards. But in the other half of trials, the facilitator could see what was shown to the child. When their facilitator knew what the card depicted, both children typed out correct answers on all 10 of the trials. However, when the picture was shown only to the children and not to their facilitator, one child was unable to identify any of the pictures correctly, and the other got only 2 out of 10 correct. On the basis of this kind of evidence, the American Psychological Association passed a resolution in 1994 denouncing the validity of facilitated communication.

The rise and fall of this controversial technique was fraught with heartache and dashed hopes. But it also illuminated something rather interesting about human psychology. In practically all of the cases where communicated messages were deemed written by the facilitator and not the child, the facilitators adamantly and fervently believed that they had not and could not have constructed the thoughts that had been typed out on paper. But the research clearly suggests that they had played an integral role. Although their conscious, cognitive system produced the belief that they were merely helping their pupil control his or her muscles, their unconscious, experiential system was likely guiding their pupil’s finger toward each letter to spell out meaningful words, phrases, and ideas.

Dual Process Theories

The core idea that thinking is governed by two systems of thought that operate relatively independently of one another forms the basis for a number of theories that you’ll encounter in this textbook. These theories are often referred to as dual process theories because they posit two ways of processing information. They have been developed to explain wide-

Dual process theories

Theories that are used to explain a wide range of phenomena by positing two ways of processing information.

86

To appreciate the gist of these theories, let’s analyze what you are doing right now. You made a conscious intention to read your social psych textbook, and you’re following through with it, pushing distracting thoughts about other matters out of your mind. You are able to consciously think about the concepts and ideas that you’re reading about, and perhaps you are going further to elaborate on that information—

At the same time that your cognitive system is busy with rational thinking, your experiential system operates in the background, controlling your more automatic thoughts and behaviors. You might read a sentence about a lazy black dog yawning and lying down, and might find yourself yawning involuntarily, even though you don’t feel the slightest bit tired. Or your favorite song might come on and, before you are consciously aware of it, you find yourself in a better mood. It is because these two systems can operate independently of each other that well-

The two systems have different ways of organizing information. The cognitive system uses a system of rules to fit ideas into logical patterns. Much as your intuitive understanding of English grammar tells you that something is wrong with the statement “Store Jane to the goes,” your cognitive system uses a type of grammar to detect when ideas fit and don’t fit. In this way, it can think critically, plan behavior, and make deliberate decisions. By contrast, the experiential system is guided by automatic associations among stimuli, concepts, and behaviors that have been repeatedly associated through our personal life history of learning. Because of the vast array of information in the world, our brains have evolved to learn from repetition. After repeatedly observing that dark clouds in the sky are often followed by rain, we automatically form an association between clouds and rain. The experiential system organizes these associations into an elaborate network of knowledge.

Because the experiential system stores a large collection of well-

Think ABOUT

Imagine that you could win money by closing your eyes and picking a red marble from a jar filled with many colored marbles. Let’s say you can choose to draw a marble from either a small jar with one red marble and nine marbles of other colors or from a large jar with 10 red marbles and 90 marbles of other colors. Which jar would you choose? Intuitively, it seems as if the chances are better with more possible winning marbles, even though statistically, and therefore rationally, this is not true: The chances of winning the money are equal for the two jars. Yet a large majority of people choose the large jar with 10 red marbles rather than the small jar with one (Kirkpatrick & Epstein, 1992).

Heuristics

Mental short cuts, or rules of thumb, that are used for making judgments and decisions.

The marble-

87

APPLICATION: Two Routes to Engaging in Risky Health Behavior

|

APPLICATION: |

| Two Routes to Engaging in Risky Health Behavior |

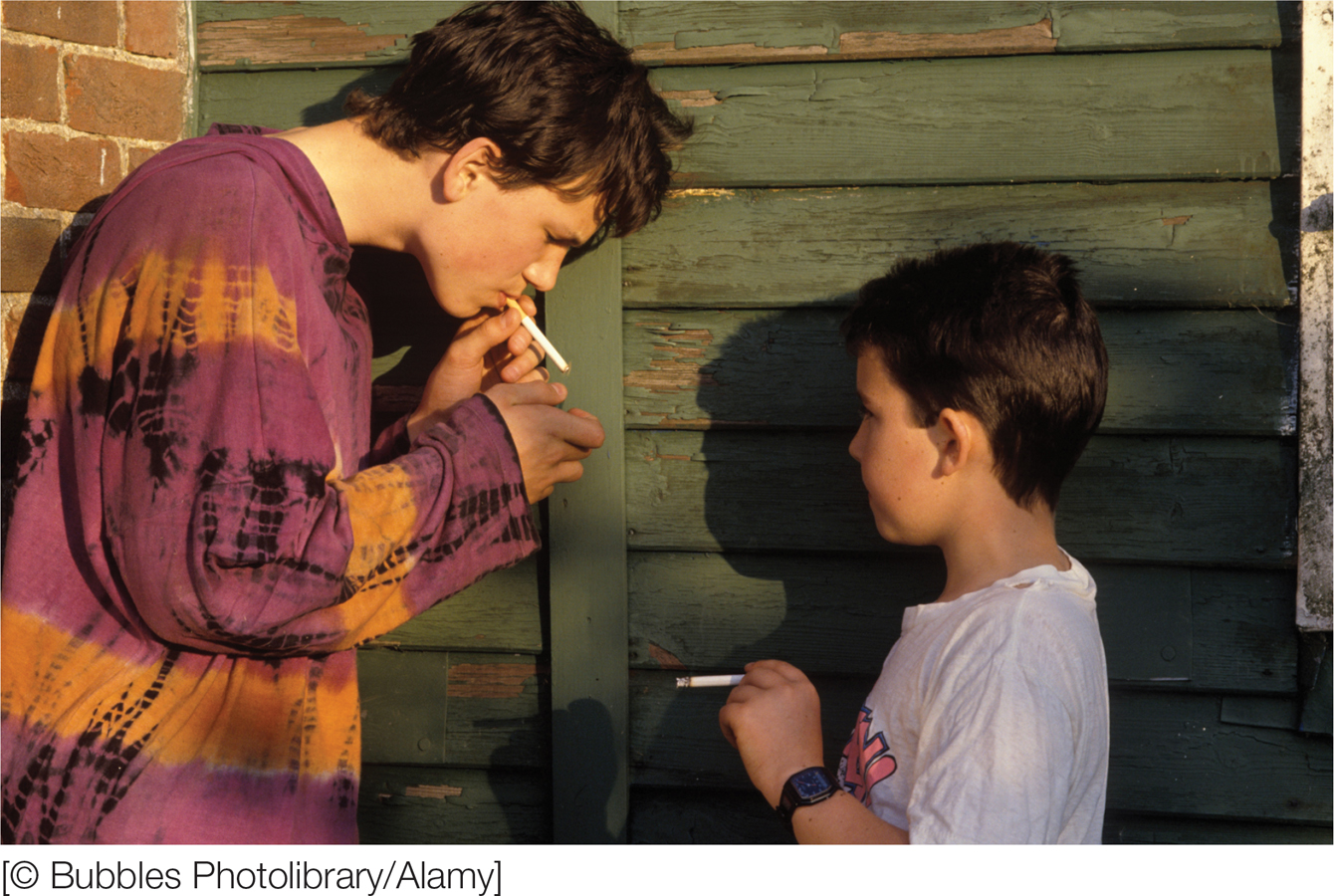

Dual process theories have enabled us to understand a number of important decisions that people make, including those that affect their physical health. The decision, for example, to engage in risky behavior such as smoking or unprotected sex can be influenced by our conscious intentions (“No way would I have unprotected sex!”), but unfortunately, in the heat of the moment, these conscious intentions can fall by the wayside. Rather, it is often people’s experientially derived willingness to engage in risky behavior that better predicts whether they will do so (Gerrard et al., 2008). These experiential feelings of willingness are strongly influenced by the images and associations that people have developed for a given behavior. For example, if adolescents’ experiential system associates smokers with a cool rebel image, they are more willing to try smoking should the opportunity arise, even if they consciously report having little intention of lighting up (Gerrard et al., 2005).

If an adolescent’s experiential system associates smoking as something that is cool, they are more likely to try it even if they are consciously aware of the dangers.

[© Bubbles Photolibrary/Alamy]

Implicit and Explicit Attitudes

Attitudes are emotional reactions to people, objects, and ideas. If we have two systems for thinking, does that mean we have two ways of evaluating something as good or bad? The answer is “yes” according to dual process theories of attitudes (Gawronski & Bodenhausen, 2006; Nosek, 2007). According to these theories, implicit attitudes are based on automatic associations that make up the experiential system. Some automatic associations can be passed on genetically through evolution (such as an automatic fear response to snakes; Öhman & Mineka, 2003), but most are learned from our culture (such as a negative attitude toward eating pork or fried ants). By contrast, explicit attitudes are often reported consciously through the cognitive system.

Implicit attitudes

Automatic associations based on previous learning through the experiential system.

Explicit attitudes

Attitudes people are consciously aware of through the cognitive system.

Because we have no direct conscious access to our experiential system, measuring people’s implicit attitudes requires a bit of cleverness. One popular task developed by Tony Greenwald and colleagues is the implicit association test (Greenwald et al., 1998). We’ll be describing this task in more detail in chapter 8, where we look more closely at how attitudes are formed and change. We’ll also return to it in chapter 10 because the study of implicit attitudes has been extremely important in our understanding of prejudice. For now, the point to remember is that this task measures the degree to which a person mentally associates two concepts (e.g., “flowers” and “pleasant”), essentially by measuring how quickly she or he can lump together examples of Concept 1 (rose, petunia, tulip) alongside examples of Concept 2 (happy, lucky, freedom). If you are like the average person (and not an entomologist), you’d probably be quicker to throw these flower and pleasant words in the same mental file folder than to group the same pleasant words with insect names such as flea, locust, and maggot. It’s this difference in speed that tells us something about your implicit attitude toward flowers relative to insects, which may or may not be the same as what you would report explicitly on a questionnaire.

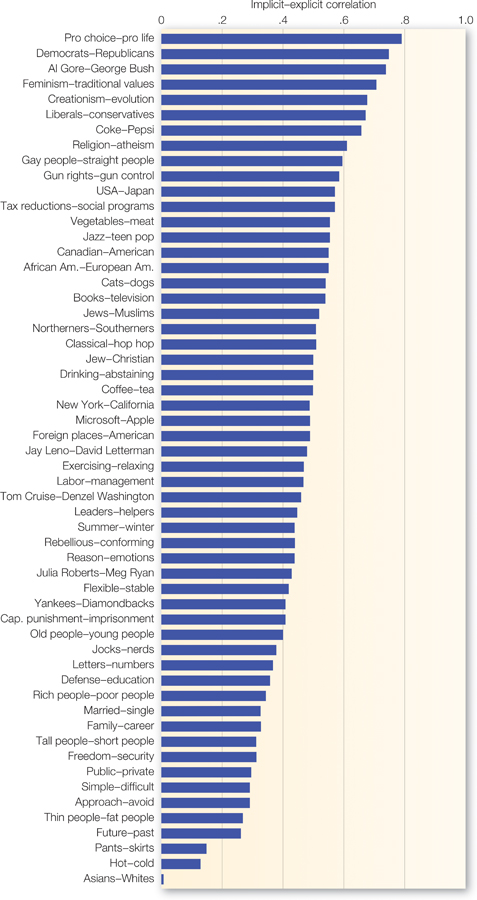

FIGURE 3.3

Implicit and Explicit Attitudes

On some issues, such as those at the top of this graph, people’s implicit and explicit attitudes are highly related; for other issues, the two types of attitudes are quite distinct.

[Data source: Nosek (2007)]

88

If the cognitive and experiential systems can both produce attitudes, and if these two systems operate independently of one another, does that mean that the same person can have different attitudes toward the same thing? The answer, again, is “yes.” To illustrate, when volunteers in one study (Nosek, 2005) were asked whether they prefer dogs or cats, what they consciously said—that is, their explicit attitude—

As shown in FIGURE 3.3, some attitudes are pretty similar when assessed implicitly or explicitly (Nosek, 2007). For example, in a study on judging political parties, the correlation of about .75 suggests that people’s reported party preferences on a questionnaire correlate quite strongly with their automatic evaluations of Republicans and Democrats. Other attitudes can be quite distinct, so the preference people say they have for family versus career might be only weakly correlated (about .30) with their implicit attitude for one over the other. Our implicit and explicit attitudes are more likely to align when we feel strongly about the issue in question, have given it a lot of thought, and feel comfortable expressing our attitudes (Nosek, 2007). On the other hand, when we are explicitly undecided about an issue, our implicit attitudes predict our later explicit preferences (Galdi et al., 2008). It seems that our experiential system is a bit of a backseat driver at times, whispering directions when our cognitive system is not sure which way to turn.

Automaticity and Controlled Processes

The example of the German Shepherd in the dark alley illustrates how the experiential system guides simple behaviors such as automatic reactions to the environment. But this system guides behavior in more sophisticated ways, as well. In particular, it can control the behaviors necessary to reach our goals. By building up mental associations through routine interactions with the physical and social environment, we can automatize certain behaviors, meaning that we can perform those behaviors without devoting much conscious attention to what we are doing. It is as though we were on autopilot. Think about how you can brush your teeth, drive home from work, or go through the grocery checkout lane without much thought. Such automatization of behaviors is highly adaptive, because it allows us to accomplish goals while saving our mental energy.

But what happens when we encounter a novel challenge that our automatized routine is not prepared to handle? Imagine that you are brushing your teeth with your electronic toothbrush, just as you’ve done every day for the past few years, and all of a sudden the toothbrush stops working. Your experiential system probably won’t be able to handle this situation, because it does not have a set of well-

89

90

We are aware that controlled processes are necessary either to get the job done or to counteract automatic processes that are not working as they should. For example, you consciously have to remind yourself to stop by the drugstore to pick up a new toothbrush battery because your automatic tendency will be to drive straight home.

We are motivated to exert control over our thoughts and behaviors. You need to care enough about getting your toothbrush fixed to change your usual habit of driving home.

We have the ability to consider our thoughts and actions at a more conscious level, because controlled processes require more mental effort. Sometimes we do not have enough cognitive resources to engage controlled ways of thinking. In these cases, the need for nonspecific closure kicks in, usually leading us to think and act in ways that are familiar and automatic. For example, after a long, exhausting day studying at the library, you may be more likely to fall back on unconscious routines and habits (such as driving straight home) rather than working toward new, consciously chosen goals (such as getting that new toothbrush battery) even if you’re aware that you need to remind yourself and are motivated to do so.

By knowing that these three conditions must be in place for the cognitive system to operate, researchers have a powerful way of testing dual process theories in the laboratory. If the cognitive system’s style of deliberate, effortful thinking requires awareness, motivation, and ability, then when people are put into situations where one or more of these conditions is missing, the cognitive system will lose its control over thinking and behavior. For example, if people are asked to memorize a long series of numbers, they lose the ability to focus attention on difficult decisions. In these situations, the experiential system will take over, because it can operate automatically without awareness, motivation, and ability; hence, people will tend to think and act more on the basis of automatic associations, heuristics, and gut-

The Smart Unconscious

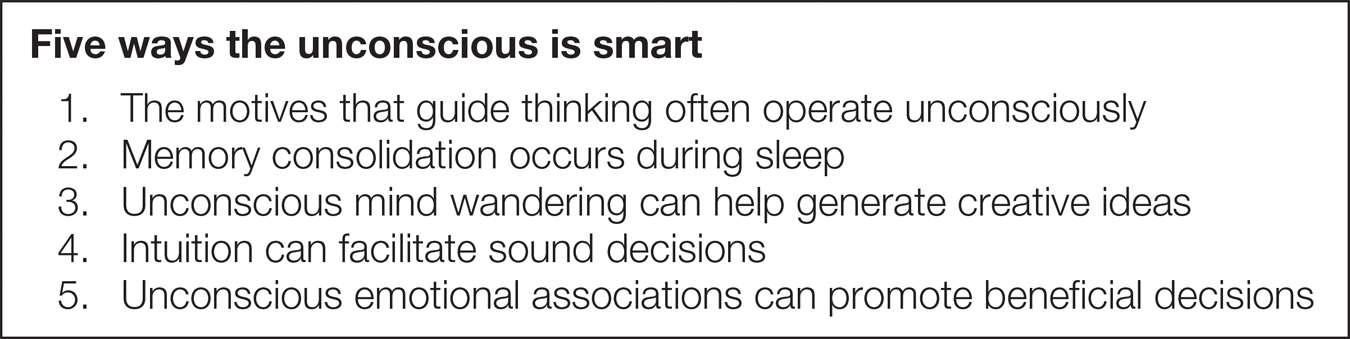

FIGURE 3.4

The Smart Unconscious

There are five ways the unconscious is smart.

Although it is tempting to view the conscious, rational cognitive system as the entire basis of human intelligence, and the experiential unconscious as more primitive, in actuality the unconscious is quite smart in at least five ways (FIGURE 3.4). For one, the basic motives that we said earlier guide social cognition—

91

Fourth, intuition plays a critical role in good decision making. It was long believed that successful decision making relies on a conscious, systematic, and deliberative process of weighing costs and benefits. In choosing a college, you might have been encouraged to weigh the pros and cons of each school, scrupulously comparing features such as the availability of student aid and the student-

In many cases, though, we fail to listen to our unconscious feelings when forming attitudes and making decisions. One reason for this is that we often have difficulty verbalizing—

In fact, when we think consciously about why we hold an attitude toward something, we often come up with a story that sounds reasonable but that does a poorer job than our gut feelings at predicting later behavior (Wilson et al., 1989). In one study (Wilson & Kraft, 1993), some participants were first asked to analyze the reasons that they felt the way they did about their current romantic relationship, and were then asked to rate their overall satisfaction with the relationship. Another group of participants did not do a reasoned analysis; they just rated their overall satisfaction on the basis of their gut feelings. You might think that the people led to analyze their reasons would figure out how they really felt about the relationship, so that their satisfaction ratings would predict whether their relationship stayed together or not. But the results revealed the exact opposite. It was the people asked to rate their satisfaction based on their gut feelings whose satisfaction ratings predicted whether they were still dating that partner several months later. As for the people asked to think hard about why they felt what they felt, their satisfaction ratings did not predict the outcome of their relationship.

A fifth way that the unconscious is smart is that our unconscious evaluations are essential for good judgment. According to Damasio’s (2001) somatic marker hypothesis, there are certain somatic (i.e., bodily) changes that people experience as an emotion. These somatic changes become automatically associated with the positive or negative contexts for that emotion. When people encounter those contexts again, the somatic changes become a marker or a cue for what will happen next, helping to shape their decisions even without any conscious understanding of what they are doing. We can see this when we compare the decisions made by healthy adults with those made by adults who have suffered damage to areas of the brain responsible for social judgments, particularly the ventromedial sector of the prefrontal cortex.

Somatic marker hypothesis

The idea that changes in the body, experienced as emotion, guide decision making.

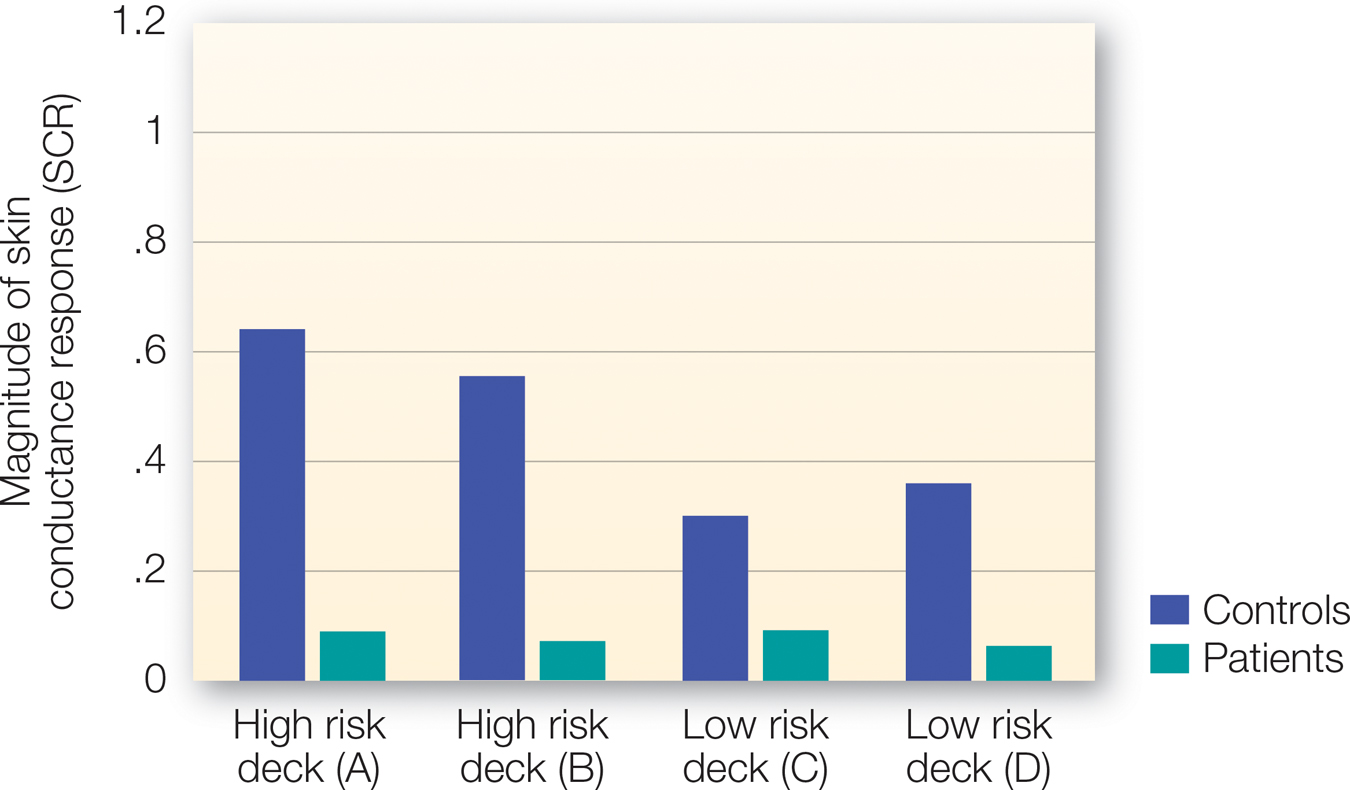

FIGURE 3.5

Somatic Markers of Risk

After playing a gambling game with both a high-

[Data source: Bechara et al. (1996)]

92

Here’s an example of a typical study. Participants are given a gambling task in which their choice of cards from four different decks can either win or lose them money. Two of the decks are risky; they can give big payouts, but choosing from them repeatedly over the course of the game is a losing strategy. The other two decks give more modest payouts, but the losses are milder as well, and a normal participant eventually learns to stick to these less risky options. Patients with ventromedial damage to the prefrontal cortex, however, don’t learn to avoid the risky decks. Why do these people continue to make high-

We don’t need to be consciously aware of how our brain is interpreting our emotional associations for those emotions to aid our decision making. In one study (Bechara et al., 1997), 30% of normal participants were unable to explain why they chose cards from one deck more or less than from another. They had no conscious understanding of the patterns that had shaped their decision making over the course of the task, yet they showed the same pattern of improved performance as the participants who had developed a clear hunch that two of the decks were riskier than the others.

APPLICATION: Can the Unconscious Help Us Make Better Health Decisions?

|

APPLICATION: |

| Can the Unconscious Help Us Make Better Health Decisions? |

Medical decision aids use a rational approach to guide people through medical treatment options, but some research suggests that the intuitive system can better integrate the role of emotion in decision making.

[© Sonda Dawes/The Image Works]

There is a big push in the health care field to assist patients in making more informed medical decisions. You or someone you know may have encountered some of these so-

But is conscious reasoning always the best way to make these decisions? Recent research suggests that perhaps even medical decisions can benefit from some input from the intuitive processing system (de Vries et al., 2013). One reason for this may be that the intuitive system is better able to integrate feelings and emotions that can play a key role in treatment adherence. Although the potential benefits of intuitive processing by no means suggest that we should avoid information or careful reasoning in health and other important decisions, it does highlight the possibility that complex decisions may best be made by integrating conscious and unconscious processes (Nordgren et al., 2011).

93

|

Social cognition is governed by two systems of thinking: a cognitive system that is conscious, rational, and controlled; and an experiential system that is unconscious, intuitive, and automatic. |

|

|---|---|

|

The two ways of thinking influence attitudes and behavior Implicit attitudes are unconscious, automatic, and based on learned associations (often called heuristics). Conscious, explicit attitudes are relatively independent of implicit attitudes. Hence, the same person can hold opposing implicit and explicit attitudes toward the same thing. Routine behaviors can become automatic, but in novel situations, the cognitive system takes over to make deliberate, reasoned judgments and decisions. The cognitive system requires awareness, motivation, and ability. If these conditions are not met, the cognitive system is interrupted, whereas the experiential system is relatively unimpeded. |

The unconscious can be smart The unconscious does “smart” things such as consolidating memories and guiding decision making. |