5.2 How Do We Come to Know the Self?

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan;

The proper study of mankind is Man.

—Alexander Pope (English poet, 1688–

Although our cultural and social environments shape the types of knowledge we have about the self, the self-

How do people discover which attributes define who they are and what sets them apart from others? Next we consider three ways that people learn about themselves over the course of their everyday social interactions: the appraisals they get from others, their social comparisons, and their self-

Reflected Appraisals: Seeing Ourselves Through the Eyes of Others

Two 20th-

Symbolic interactionism

The perspective that people use their understanding of how significant people in their lives view them as the primary basis for knowing and evaluating themselves.

Looking glass self

The idea that significant people in our lives reflect back to us (much like a looking glass, or mirror) who we are by how they behave toward us.

Appraisals

What other people think about us.

Charles Cooley (left) and George Herbert Mead (right) developed the idea that people learn about and judge themselves on the basis of how other people perceive them.

[Left: Photographer unknown, c. 1902; right: The Granger Collection, NYC. All rights reserved.]

People use others’ appraisals not only to know their attributes but also to evaluate themselves and their actions as good or bad. For example, a person might feel bad about the pile of laundry on the floor because she imagines Mom’s voice saying, “You are such a slob!” Because people internalize others’ appraisals, they evaluate themselves as if those other people were in their heads, observing them act. Cooley also pointed out that a person’s self-

Research supports many of Mead’s and Cooley’s insights. In fact, Baldwin and colleagues (1990) hypothesized that even unconscious reminders of approval and disapproval from significant others would influence self-

If you consider Pope Francis to be a significant figure in your life, how do you think being exposed to this image of his scowling expression would make you feel about yourself? What if you had just been engaging in some questionable activity?

[Filippo Monteforte/AFP/Getty Images]

159

Mead went beyond Cooley’s emphasis on appraisals of particular significant others to propose that people also internalize an image of a generalized other, a mental representation of how people, on average, appraise the self. This generalized other becomes the internal audience or perspective by which people view and judge themselves. A study consistent with this idea showed that overweight people are significantly less happy if they live in a society that stigmatizes obesity and values thinness than if they live in a society in which obesity is common and accepted (Pinhey et al., 1997). These findings suggest that people can think poorly about themselves because they take the perspective of a generalized other who views them negatively.

Although this research suggests that the self-

Reflected appraisals

What we think other people think about us.

This point is readily apparent when we consider people’s perceptions of their physical attractiveness. If you ask Person A how physically attractive she or he is, and then you ask Person A’s romantic partners and close friends to rate Person A’s attractiveness, you will find that those ratings do not match up entirely. Indeed, the average correlation between the ratings is only about .24 (Feingold, 1988). That means that some people overrate their attractiveness; other people underrate it. In both cases, people’s perceptions of themselves are derived from factors other than the appraisals they receive from others.

The gap between reflected appraisals and actual appraisals is partly due to distortions in the feedback that senders provide to us: People often try to be tactful, softening their feedback to others (e.g., DePaulo & Kashy, 1998). But people also selectively interpret the feedback they are given. In one study, O’Connor and Dyce (1993) interviewed members of bar bands, asking band members to rate the ability of others in the band (actual appraisals of band mates), what feedback they gave to others in the band about their abilities, and how those individuals perceived their own ability. The researchers found that band members were pretty honest with their band mates, just a little more positive in their feedback then their private evaluations of them would suggest. However, each individual seemed to think his band mates appreciated his musical ability less than they actually did and less than the feedback he got from them would suggest. So each band member seemed to let his own insecurities color how he was perceived by others, creating a gap between reflected appraisals and actual appraisals.

160

Social Comparison: Knowing the Self Through Comparison With Others

A second way in which people learn who they are is by comparing themselves with others. Leon Festinger (1954) first described this process in his social comparison theory. He pointed out that people often don’t have an objective way of knowing where they stand on an attribute. Therefore, many, if not most, of their beliefs about themselves are on dimensions that can be assessed only relative to others. Consider, for example, whether you are a fast runner. Well, compared with a four-

Social comparison theory

The theory that people come to know themselves partly by comparing themselves with similar others.

Downward comparison

Comparing oneself with those who are worse off.

Upward comparison

Comparing oneself with those who are better off.

Consider, for example, a job interview situation where one is likely to be uncertain about one’s standing on certain characteristics. One study (Morse & Gergen, 1970) used this context to demonstrate how social comparisons can influence people’s views of themselves. College-

Just as reflected appraisals sometimes are a poor match to what people really think of themselves, the self-

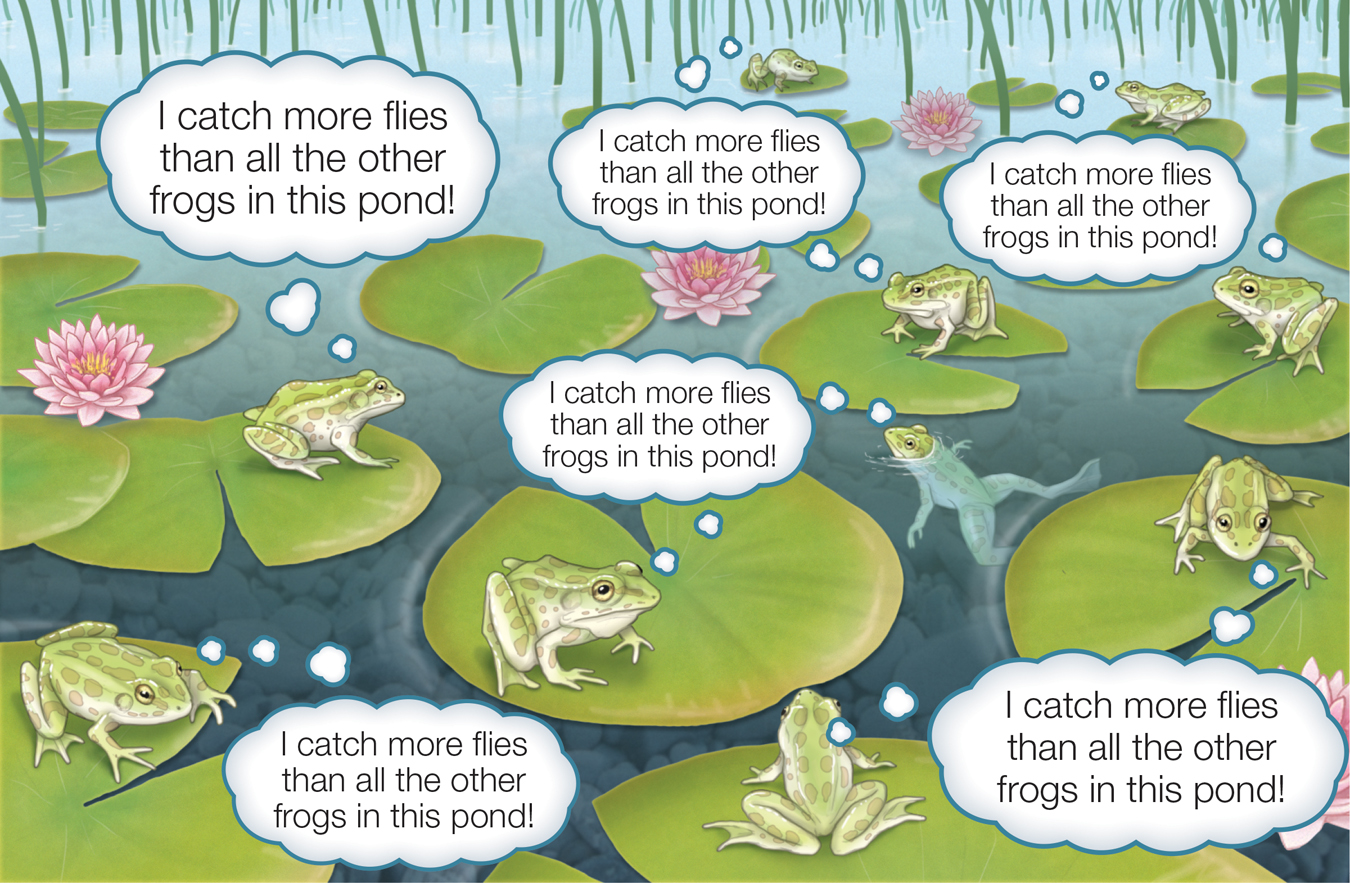

One particularly well-

Better than average effect

The tendency to rank oneself higher than most people on positive attributes.

161

But why else do people make this common error? To find out, Dave Dunning and colleagues (2003) reviewed evidence from various studies that examined which people are most likely to overestimate their abilities and knowledge in a variety of domains, including performance in psychology, reading comprehension, grammar, and logic tests, sense of humor, debating ability, hunters’ knowledge of firearms, medical residents’ interviewing skills, and medical lab technicians’ problem-

Dunning and colleagues offer a simple but interesting explanation for this phenomenon. If you ask people how good they are as writers, most people would rate themselves as better than average. But why would the worst writers do this? Because they lack the knowledge of writing—

This finding raises an important question: Can people be trained to assess their weaknesses accurately, so that they know what they need to do to improve? To find out, Kruger and Dunning (1999) had participants take a test of logic. Poor performers greatly overestimated their performance. Then they trained some of these poor performers in how to distinguish correct from incorrect answers and gave them their tests to look over. Their self-

Thus, ignorance of ignorance is one source of inaccuracy in evaluating the self in comparison to others. As people get smarter and become aware of their own ignorance, they tend to become more accurate about themselves. As Dunning and colleagues (2003) note, although knowledge of your deficiencies can be humbling, it is often better than remaining blissfully unaware, because you won’t be motivated to take steps to improve until you realize you have deficiencies in skills or knowledge.

Self-perception Theory: Knowing the Self by Observing One’s Own Behavior

According to self-

Self-perception theory

The theory that people sometimes infer their attitudes and attributes by observing their behavior and the situation in which it occurs.

162

We are most likely to learn about ourselves through this self-

In a less dramatic way, we often find ourselves relying more on self-

We don’t use self-

Using One’s Feelings to Know the Self

Lift your chin up, and then down, and repeat this motor movement. This is a pretty basic physical act. Taking it on its own, we might not imagine that it would have any power to influence our judgment. But think about when we usually engage the muscles in our head and neck in this way. Often it is when we are signaling our agreement with something. Could this mean that our brain unconsciously uses this same sequence of muscular movements to infer agreement? Research suggests that the answer is yes.

For instance, Wells and Petty (1980) had participants listen to an audio recording that included an editorial advocating tuition increases. Under the guise of testing the durability of the headphones, participants were asked to move their chins up and down or from side to side while listening to the tape. Afterward, participants were asked how much they thought tuition should be. Those who had been nodding their heads the entire time reported tuition numbers that were about 38% higher than those who had been shaking their heads!

Another example comes from work on the facial feedback hypothesis. We become so accustomed to expressing our emotional states through our facial expressions that changes in our facial movements become a signal of the emotion we might be feeling. In the first test of this hypothesis, James Laird (1974) attached electrodes to participants’ faces and asked them to evaluate a series of cartoons. Before showing the participants each cartoon, he gave them instructions to contract their facial muscles or squeeze their eyebrows together in certain ways, such as, “Use your cheek muscles to pull the corners of your lips outward.” Participants were told that the electrodes were measuring the activity of their facial muscles, but in reality Laird was subtly inducing them to make either a smiling expression or a frown. Those induced to make the smiling face rated the cartoons as funnier and reported feeling happier than those induced to frown. You can try this out at home without the fancy electrodes. Try putting a pen or pencil between your teeth as shown in the photo on the left. This activates your zygomaticus major muscles, forcing your lips to draw back as they do when you smile. Now hold the pen or pencil with your lips as shown in the photo below. This activates your corrugator supercilii muscles, which you use when you are frowning. In one study using this technique, participants who (unknowingly) “smiled” rated cartoons as more humorous than did participants in the control condition, whereas participants who held a marker with their lips (the “frowners”) found them less amusing (Strack et al., 1988). Participants seemed unconsciously to infer, “If I am smiling (or frowning), I must be amused (or turned off).”

Facial feedback hypothesis

The idea that changes in facial expression elicit emotions associated with those expressions.

Facial movements provide signals as to what emotions we might be feeling.

[Mark Landau]

163

The basic idea of self-

One of the reasons we can be wrong is that we aren’t very good at accurately judging how situations influence our thoughts and behaviors. We underestimate the effects of some situational factors and overestimate the effects of others. For example, Nisbett and Wilson (1977b) showed that people liked a movie less if it was out of focus part of the time but were unaffected by a loud noise outside the room where the movie was showing. However, when the researchers asked participants about the factors that influenced their enjoyment, the participants thought the focus problems did not affect their liking (underestimating the effect) and that the loud noise did (overestimating the effect).

In much the same way as our memory is not a verbatim record of the past (see chapter 4) but is instead reconstructed online, our conscious experience of ourselves is constructed online. As a result it is susceptible to error and bias. This doesn’t mean our beliefs about why we feel and behave the way we do are always wrong, but rather that they are often, if not always, based on an imperfect inference process that sometimes leads to inaccurate or incomplete understanding. If you just found out a close friend died, and you felt very sad, you would probably be right in inferring that this news made you sad. But so would an objective observer who witnessed you learning of this news but did not have access to your internal feelings. At other times, the cause of negative feelings may not be so obvious. You might erroneously attribute them to particular reasons, such as lack of sleep, when they are really due to something else. In fact, studies comparing daily fluctuations in mood with other things going on in people’s day-

164

Using the Self to Know One’s Feelings

Self-

emotion = arousal × cognitive label

Two-factor theory of emotion

The theory that people’s emotions are the product of both their arousal level and how they interpret that arousal.

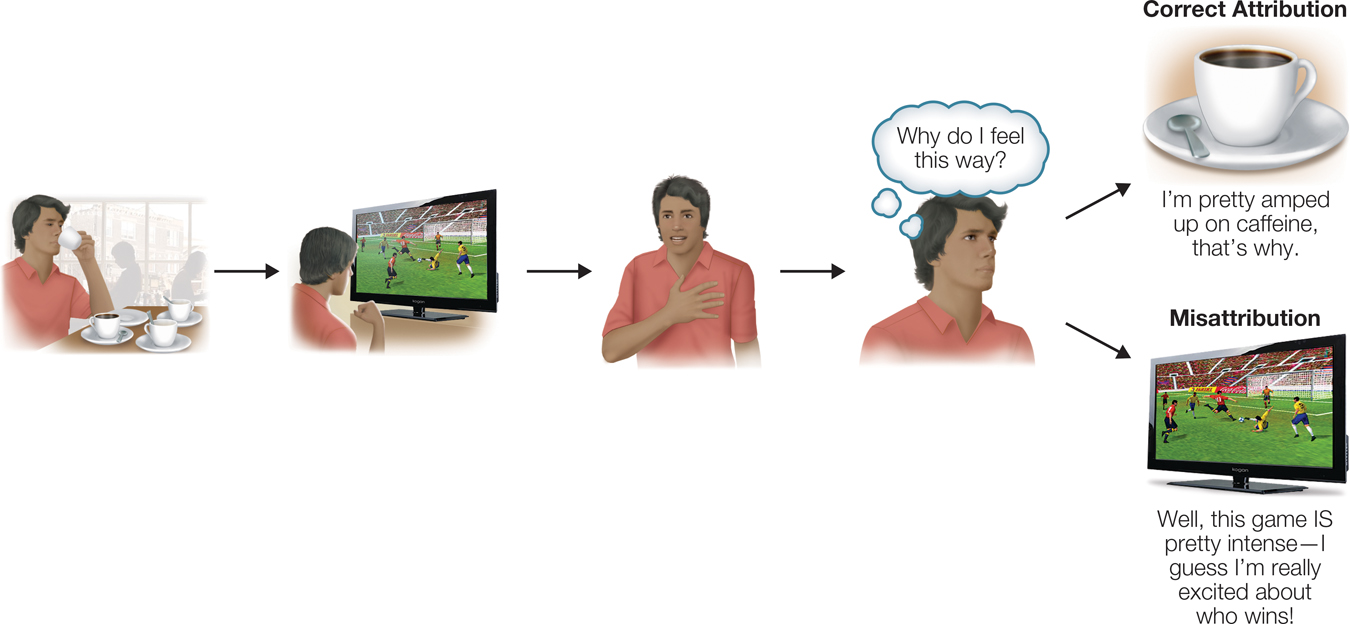

FIGURE 5.2

Misattribution of Arousal and Emotion

When we observe our own behavior to figure out why we feel aroused, we can make mistakes about where that arousal came from. As a result, we can experience emotions that are fueled by something else entirely.

One startling implication of this theory is that the same arousal could be attributed to one or another emotion, depending on the self-

In the first experiment to test this idea, Schachter and Singer (1962) gave participants an injection of epinephrine (also known as adrenaline), which causes arousal in the sympathetic nervous system. However, they told participants that the study concerned the effects of a drug that influences memory and that the injection was a dose of the memory-

165

This phenomenon has become known as misattribution of arousal, which occurs when we ascribe arousal resulting from one source (in the case of the first study, an injection) to a different source, and therefore experiencing emotions that we wouldn’t normally feel in response to a stimulus. Although certain emotions do induce very specific and differentiated physiological responses (e.g., Barrett et al., 2007; Reisenzein, 1983), initial arousal states often are subjectively ambiguous; thus, people’s emotions can be greatly influenced by their interpretation of the circumstances of the arousal. This research shows how self-

Misattribution of arousal

Ascribing arousal resulting from one source to a different source.

Understanding how people use self-

Of course, outside the confines of social psychology labs, rarely are people unwittingly given injections of adrenaline or placebo pills. This led Dolf Zillmann (e.g., Zillmann et al., 1972) to wonder: Under what conditions does misattribution of arousal occur in everyday life? According to his excitation transfer theory, misattribution happens when an individual is physiologically aroused by an initial stimulus and then a short time later encounters a second, potentially emotionally provocative, stimulus. Leftover or residual excitation caused by the first event becomes misattributed or, using Zillmann’s terminology, transferred, to the reaction to the second stimulus, resulting in an intensified emotional response to that second stimulus.

Excitation transfer theory

The idea that leftover arousal caused by an initial event can intensify emotional reactions to a second event.

FIGURE 5.3

Excitation Transfer

Physiological arousal created in one context can be misattributed, intensifying emotional reactions to a subsequently encountered stimulus in an unrelated context.

[Data source: Zillmann et al. (1972)]

In one study demonstrating this phenomenon (Zillmann et al., 1972), half the participants were asked to exercise by riding a stationary bike vigorously for two and a half minutes. The other participants were seated comfortably at a table and asked to pass thread through discs with holes (not particularly arousing!). In the second part of the study, participants were provoked with insults or not provoked by another participant (in actuality, a confederate). Participants were then given an opportunity to punish the other participant by delivering painful electric shocks. As you see in FIGURE 5.3, the unprovoked participants were not very aggressive, regardless of whether they exercised. Provoked participants, however, were more aggressive if they exercised than if they did not, suggesting that they misattributed arousal as anger in response to the provocation, thus producing anger-

166

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

The Self Lost or Found in Black Swan

The Self Lost or Found in Black Swan

The 2010 film Black Swan, directed by Darren Aronofsky (Medavoy et al., 2010) is a dark parable of how the influence of cultural values can distort our perceptions of ourselves.

The film is set in the intense subculture of ballet, which idealizes perfection in physical movement and form, especially for women. In this way, the ballet world is a distillation of broader cultural tendencies to view the female body as an object and to mask the physicality of the body with an idealized veneer of beauty and grace (e.g., Goldenberg, 2013). (We will discuss these ideas further in chapter 14). This subculture takes a toll on women’s health: The prevalence of eating disorders is estimated to be 25 times higher in ballerinas than in other women similar in age and backgrounds (Dunning, 1997).

The film’s protagonist, Nina, played by Natalie Portman, is a somewhat uptight and self-

In addition to defining herself through these reflected appraisals, Nina is also quite intensely caught up in social comparison. The arrival of Lily, a dancer played by Mila Kunis, marks the beginning of Nina’s dark descent into negative self-

These cinematic devices not only create a visceral tension to the film but also capture nicely how molding oneself to the values of others alters one’s view of reality. Some film critics have complained that Nina’s own motivation for ballet is never really conveyed (Stevens, D., Dec. 2, 2010, Nut-

Part of what drives motivation toward any goal is self-

Of course, mirrors also symbolize our own vanity. In the final scenes of the movie (spoiler alert!), Nina’s obsession with living up to ideals of perfection reaches the breaking point. Her grasp on reality finally is lost when she imagines pushing her rival, Lily, into a mirror and shattering it during an intermission in the ballet performance. Although she envisions her competitor being destroyed, it is revealed in the next scene—

These findings show how the misattribution of arousal, leading to intensified emotional reactions, can happen in the course of daily events. Here’s just one of many examples of how this process can affect people: Imagine a typical teenage boy getting off an intense roller-

167

|

How Do We Come to Know the Self? |

|

Reflections, comparisons, and self- |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Reflection People learn about the self by assessing how significant others behave toward them. Others serve as a mirror, or “looking glass.” Nevertheless, people do not always perceive accurately what others think of them. |

Comparison People learn about the self by comparing themselves with others. Upward and downward social comparisons have diverging effects on self- Comparisons are often biased in the self’s favor. |

Self- People learn about the self by observing their own behavior and making inferences about their traits, abilities, and values. However, these inferences can be wrong. A self- |