5.3 Self-regulation: Here’s What the “I” Can Do for You

Now that we’ve discussed the self-concept (what James called the Me), it’s time to turn to the ego, the part of the self that drives and controls behavior (what James called the I). We’ll explore self-regulation—how people decide what goals to pursue and how they attempt to guide their thoughts, feelings, and behavior to reach those goals.

Self-regulation

The process of guiding one’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior to reach desired goals.

The ability to self-regulate is fundamentally based on three key capacities of the human mind that emerged as the hominid cerebral cortex evolved. First, we are self-aware, able to assess our thoughts, feelings, and behavior in relation to the world around us. Second, we’re able to think about overarching goals, such as curing cancer or winning an Olympic gold medal, and about abstract symbols and concepts such as kindness or honesty. Third, we are able to mentally travel in time, to pop out of the here and now to reach back to our past and envision hypothetical realities in the future.

These three capacities provide our species with a tremendous degree of flexibility and choice, a freedom to respond to a given situation in a much wider range of ways than is possible for any other animal on the planet. This means we humans can accomplish great things, such as developing, or at least conceiving of, societies in which fundamental rights are granted to all citizens, and getting some control over the effects of harmful viruses, such as HIV. On the other hand, these components of mental freedom can also lead to great evil, because we can use them to plan and execute large-scale acts of violence and create technology that threatens our future survival. Let’s examine in more detail the mental capacities for self-regulation that make possible these magnificent and horrific facets of our species.

The Role of Self-awareness in Self-regulation

Although it’s fairly easy to ask people about themselves and thereby study the self-concept, investigating the ego—the behind-the-scenes executive function of the self—is more difficult. Discussion of the regulatory function of the ego goes as far back in psychology as the 19th century, but the first major breakthrough in studying self-regulation came in 1972, when Shelley Duval and Bob Wicklund developed self-awareness theory.

Self-awareness theory

The theory that aspects of the self—one’s attitudes, values, and goals—will be most likely to influence behavior when attention is focused on the self.

Duval and Wicklund start with the idea that self-regulation requires the ability to think about the self. At any given moment, your attention is focused either inward on some aspect of self—things you need to get done today, your social life, whether you’re ready for your midterms—or outward on some aspect of the environment—a building, a dog catching a Frisbee, a new tune on your iPhone, and so forth. Also, your situation focuses attention on specific aspects of the self, such as attitudes and goals. In the voting booth, for instance, self-awareness would bring to mind your attitudes about political issues, but while taking an exam in class, you might find that your academic standards and aspirations come to mind.

We saw in chapter 4 how information that is salient significantly influences behavior. Duval and Wicklund make the same point regarding the self. They propose that aspects of the self—one’s attitudes, values, and goals—will be most likely to influence behavior when attention is focused in on the self, that is, when some aspect of the self is salient. The theory also asserts that when self-focused, people tend to compare their current behavior with those salient attitudes, values, and goals. In other words, self-awareness helps us become mindful of the gap between what we are doing and what we aspire to or feel we should be doing. In Freud’s terminology, directing attention onto the self activates the superego—the internal judge that compares how one currently is with internalized standards for how one should be or wants to be. Self-awareness theory further posits that if this comparison suggests that a person is falling short of internalized standards, that person experiences negative feelings and becomes motivated to get rid of those feelings.

Self-awareness theory specifies two basic ways to cope with a negative discrepancy and feel better. One is to distract yourself from self-focus, so that you stop thinking about the discrepancy between how you are and how you want to be. For example, if you found out you bombed on your first social psych test, you might go to a movie or hang out with friends as a distraction from dwelling on your failure. The other, generally more constructive, way is to commit to doing better. So to reduce the negative discrepancy, you would commit to studying harder, taking better notes, getting a tutor, and so on.

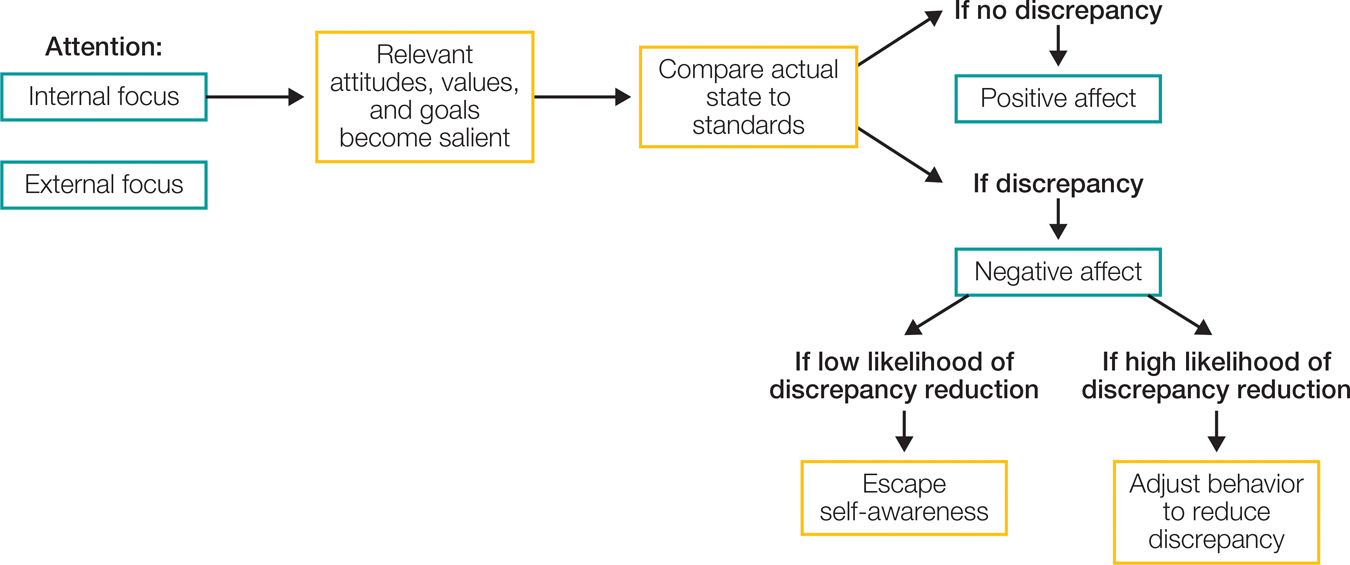

Self-awareness Theory

According to self-awareness theory, an internal focus of attention leads relevant standards to become salient. If a discrepancy is perceived when comparing one’s current state to the standard, negative affect results and motivates the person to either reduce the discrepancy or escape self-focus.

What determines whether you will avoid self-focus or commit to doing better? If you think your chances of successfully reducing the discrepancy are good, or if it’s easy enough to change your behavior, you’ll take that route. But if you think your chances are slim and the discrepancy can’t be reduced with a simple act, you’re more likely to take the distraction route or perhaps even give up on the goal entirely (Carver et al., 1979). This process is summarized in FIGURE 5.4.

Self-awareness Promotes Behaving in Line With Internal Standards

Self-awareness theory proposes a fairly elaborate process going on inside our own heads. So how could researchers test this theory? To do so, they needed a way to increase and decrease self-awareness and observe the consequences. This is a tricky problem because people tend to shift spontaneously in and out of self-focus from moment to moment.

Think ABOUT

Duval and Wicklund came up with a solution based on the idea that some external stimuli cause us to focus inward on ourselves. For example, seeing an image of ourselves in a mirror, particularly in contexts in which we don’t expect to, is likely to make us think of ourselves. Can you think of an example of this for yourself, say, a time when you were unexpectedly sitting next to a mirror at a coffee shop? In fact, exposing people to mirrors has been the most common way that psychologists have increased self-awareness. They’ve also had people hear their names or their own voices on an audio recording, pointed video cameras at people, and asked them to write an essay in which they have to use first-person pronouns such as I, me, and mine.

This trick-or-treater may be more likely to do the right thing and take one piece of candy if he catches his reflection in the window.

[Jeff Greenberg]

When researchers began randomly assigning people to be in situations that evoke high or low self-awareness, they found that, as the theory proposes, high self-awareness leads people to behave in line with their internal standards. In one classic study, Chuck Carver (1975) recruited participants who earlier had expressed either favorable or unfavorable attitudes toward using physical punishment as a teaching tool. Once they arrived at his lab, participants were given the role of teacher and asked to use electric shock to punish another student (in reality a confederate) when they made errors on a learning task. The participants were allowed to choose the intensity of the shock they would use as the punishment. To test the role of self-awareness, Carver had half the participants deliver shocks while they were in front of a mirror, whereas the other participants delivered shocks with no mirror present. Without the self-focusing mirror, participants’ prior attitudes about the use of physical punishment did not at all predict the intensity level of the shocks they chose to administer. In contrast, in the presence of the mirror, those opposed to physical punishment chose very low shock levels, whereas those in favor of physical punishment chose to administer high levels of shock. In this study, people’s behavior was guided by their personal attitudes only when they were made self-aware.

In another study, Beaman and colleagues (1979) showed that a mirror can even make Halloween trick-or-treaters more likely to follow the instruction of taking only one treat from an unattended candy bowl. Fully aware of this study, one of your authors similarly left an unattended bowl outside his door with instructions while escorting his own son around the neighborhood. But he forgot the mirror, so the bowl was quickly emptied!

These studies, and many others like them, demonstrate that our internalized attitudes, values, and goals guide our behavior only to the extent that we are self-aware. Of course, as we have discussed in earlier chapters, our attitudes and values are largely taught to us by our culture. Self-awareness thus plays a crucial role in civilizing us; it brings our behavior more in line with the morals and goals we learn from our culture. Indeed, one lab study showed that heightened self-awareness reduced student cheating on a test from 71 percent to 7 percent (Deiner & Wallbom, 1976).

APPLICATION: Escaping from Self-awareness

|

APPLICATION: |

| Escaping from Self-awareness |

We’ve seen that focusing on ourselves can lead us to behave in line with how we want to be. What happens when we perceive ourselves as falling short of our standards, but feel incapable of changing our behaviors? Self-awareness theory predicts that under these conditions, people try to escape from self-awareness. In fact, research shows that failure experiences initially direct attention to the self, but if no constructive action seems possible, people avoid self-focusing stimuli such as mirrors (Duval & Wicklund, 1972) and distract themselves with activities like watching TV (Moskalenko & Heine, 2003). A recent set of studies suggests that people may even choose unpleasant activities like shocking themselves over extended minutes of self-awareness with no external distractions (Wilson et al., 2014). Of course, when feeling positive about the self or hopeful about the future, escape from self-awareness is not needed. For example, Steenbarger and Aderman (1979) demonstrated that if participants delivered a speech poorly, they didn’t subsequently avoid self-awareness if they thought it was easy to improve their speaking abilities. However, they did avoid self-awareness if they thought their speaking ability is pretty much fixed for life.

The tendency to escape self-awareness in the face of failure with little hope for improvement may contribute to problem behaviors such as binge eating and drug and alcohol abuse (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991). This is because, as research shows, these activities tend to reduce self-focus and, therefore, any unpleasant thoughts that the self is falling short of its standards. But does everyone make equal use of this avoidance strategy? It seems likely that people who are generally high in self-awareness—who tend to think about their attitudes and feelings a lot—would be more likely to seek ways of escaping self-awareness than those individuals who are less likely to introspect.

Hull and Young (1983) examined this possibility by looking at whether people high in private self-consciousness, the trait of being generally high in self-awareness, would use alcohol as a way to escape from self-awareness. They recruited participants to take part in what they thought were two unrelated studies, one on personality and the other on alcohol preferences. (In reality the studies were related.) Participants first completed the private self-consciousness scale, indicating how much they agreed with statements such as “I’m always trying to figure myself out” (Fenigstein et al., 1975). Then they were told they did either really well or really poorly on an intelligence test. In this way, the researchers introduced a negative discrepancy between participants’ standards of success and their current performance. Believing that the first study was now complete, they walked down the hall to participate in a study on wine-tasting preferences. They were asked to taste a number of different wines and rate their preferences over a 15-minute period. Did their experiences in the earlier study affect how much alcohol they consumed? Yes: Those participants who were high in private self-consciousness and received failure feedback consumed more wine than the other participants. They were, in effect, “drinking their troubles away.”

This tendency to avoid unpleasant self-awareness by drowning one’s problems in booze has also been documented outside the laboratory. For example, Hull and colleagues (1986) found that among alcoholics who were attending a treatment program at a veterans’ hospital, those who were higher in private self-consciousness and experienced failures over the next few months were more likely to relapse. These findings, in conjunction with the experimental results, suggest that people with a generally high level of self-awareness may try to avoid confronting their own failures and inadequacies by consuming harmful levels of alcohol.

What Feelings Does Self-awareness Arouse?

At a general level, the emotions we feel when we focus internally help to keep the self on track toward meeting goals. If we sense that we are living up to our standards or making rapid progress toward a goal (such as getting an A on a midterm exam), we experience positive emotions that are reinforcing. But when we judge ourselves as falling short or making inadequate progress toward a goal, we experience anxiety, guilt, or disappointment. As we just saw, these emotions can motivate us to do better, if that seems possible, or to escape from self-awareness if change seems unlikely.

Tory Higgins’s (1989) self-discrepancy theory provides a more refined understanding of the different types of emotions that self-awareness is likely to evoke. Higgins built on the Freudian notion of the superego, which posits that during childhood, we internalize a set of standards and goals regarding ourselves. Freud proposed that these internalized standards form two clusters. The first cluster is a conscience, which focuses on how you should be. Higgins refers to this as the ought self. The second cluster is an ego-ideal, which focuses on how you want to be or what you would like to accomplish. Higgins refers to this as the ideal self.

Self-discrepancy theory

The theory that people feel anxiety when they fall short of how they ought to be, but feel sad when they fall short of how they ideally want to be.

As children, when we fall short of achieving the ought self, we anticipate that our parents might become angry and punish us or withdraw love and protection, and we feel anxious as a result. Imagine being caught gorging on cookies right before dinner. You might feel anxious in anticipation of punishment. Of course, if you refrain from eating the cookies, you would feel calm and secure instead (albeit a little hungry perhaps).

In contrast, when we fall short of the ideal self, we anticipate letting our parents down and so feel discouraged and dejected. Imagine that your parents are watching you as a child playing Little League or Bobbysox, and you strike out to end the game with your team down one and the bases loaded. No matter what your parents say, you’ll hear disappointment in their voices and see it in their faces. On the other hand, if you hit a game-winning double, they will be proud and you will feel elation and satisfaction.

Higgins argued that these same feelings arise throughout our lives when we fall short of meeting oughts and ideals. Failing to live up to the ought self elicits anxiety and guilt, because in those situations we have become used to expecting punishment. In contrast, failing to live up to the ideal self elicits dejection and sadness, because in those situations our parents reacted with disappointment.

Research on self-discrepancy theory has provided support for these ideas (Higgins, 1989). When college students were led to compare who they were at the time (the actual self) with the person they thought they should be (the ought self), they felt calmly secure if the discrepancy was small or nonexistent, but anxious and guilty if the discrepancy was large. When students were led to compare the actual self with the ideal self, small discrepancies were associated with feelings of satisfaction, but large discrepancies generated feelings of rejection and discouragement. These studies have also shown that although we all have both oughts and ideals, some people are more focused on their oughts and others more on their ideals. These distinctions, in turn, influence the types of emotions people generally experience when they fall short of their standards.

Another important factor is whether people attribute their shortcomings to something specific they did or to the type of person they are. People tend to feel guilty if they conclude that they engaged in a bad behavior, but they feel shame if they conclude they are bad persons. These attributions affect our emotional well-being. The psychologist Otto Rank (1930/1998) proposed that guilty feelings signal to us that an important social relationship is in trouble, and as a result, they motivate us to take action to repair the damage we have done. A wide range of findings support this idea (Baumeister et al., 1994). For instance, people who are likely to experience guilt about their self-discrepancies also feel more empathy for others (Tangney, 1991) and are more motivated to make up for their past mistakes by apologizing to those who are harmed and offering to make the situation better somehow (Tangney et al., 1996). On the other hand, people who tend to feel ashamed of themselves when they do something wrong show higher levels of depression (Tangney et al., 1992b) and are also more likely to turn to drugs and alcohol as a means of escaping painful feelings of self-awareness (Dearing et al., 2005). Furthermore, people who feel chronically ashamed of themselves also tend to be more angry, hostile, and suspicious of others (Tangney et al., 1992a).

Staying on Target: How Goals Motivate and Guide Action

Now that we have seen how self-awareness activates our concerns with meeting goals, and the basic distinction between oughts and ideals, let’s focus more closely on how goals help us keep our behavior on target. When we wake up in the morning, we’re likely to think about our short-term goals for the day—make breakfast, call Mom, and so forth—and we might also think about more long-term, abstract goals, such as “I’ve got to get my life together,” “Do I really want to go to law school?” and “How am I going to get out of this relationship?” In this section, we’ll consider which goals we choose to pursue, how hard we strive for them, how those goals get activated, and how goal pursuit is affected by the way we interpret our own behavior.

Pursuing Goals

Two basic components of self-regulation are choosing which goals to pursue and how much energy to direct toward pursuing a particular goal. Goals are what we strive for in order to meet our needs. They guide and energize behavior. They are associated with maintaining or approaching positive feelings or alleviating or avoiding negative feelings. People’s goals generally serve either basic survival needs or the core human psychological motivations for security or growth.

What determines the amount of our available energy that we are willing to expend on achieving a particular goal? According to expectancy-value theory (Feather, 1982), effort is based on the value or desirability of the goal multiplied by the person’s assessment of how likely it is that she will be able to attain the goal. If two goals are equally attainable, we will more strenuously pursue the more valued of the two. If two goals are equally valued, we will devote more effort to the one we perceive as more likely to be reached. If a given goal is highly valued but seems very unlikely to be attained, people won’t direct much energy toward pursuing that goal. People also consider the difficulty of achieving a particular goal (Brehm & Self, 1989). Two goals may be equally attainable, but one may require more effort than the other. If a person is committed to both goals, he will devote more energy to attain the harder goal and view it as the more desirable goal. Although people can become more energized by difficult goals they think they can attain, if they perceive that goal attainment involves more difficulty than the goal is worth, or if they come to perceive it as simply impossible, generally they will abandon the goal, reduce how attracted they are to the goal, and cease to devote further energy to it.

Expectancy-value theory

The theory that effort is based on the value or desirability of the goal, multiplied by the person’s assessment of how likely it is that she will be able to attain the goal.

The children’s story The Little Engine That Could captures the idea that expecting success energizes us to achieve our goals.

[© Universal Images Group Limited/ Alamy]

Activating Goals: Getting Turned On

Once goals are activated, they can influence thought and behavior by bringing to mind other beliefs, feelings, and past knowledge. For instance, the goal “make coffee” may seem simple enough, but it actually involves cuing up a vast amount of knowledge about kitchen faucets, electrical appliances, and cleanliness, not to mention your feelings about coffee and the belief that it will help you focus on that paper you need to write. You can imagine that more complex goals, such as ending a romantic relationship, are linked to an even larger set of associations.

We can activate goals either by consciously bringing them to mind or by being unconsciously cued by the environment. It is probably easy to think of times when you have activated a goal by self-selection, that is, when you have consciously set a goal for yourself by making a commitment to achieve some desired end state (e.g., “I’m going to get that term paper finished today”). More interesting, perhaps, is that we often pursue goals without any conscious awareness that we are doing so. Surely you are reading this book in part to move toward getting a degree and perhaps toward a career in psychology or some other field. But we suspect you are not continually consciously thinking about such long-term goals at the moment; indeed, doing so would probably interfere with learning the material and thereby work against accomplishing the very goals the activity is serving. But then what initiates our goal pursuits when we are not consciously thinking of our goals?

Bargh’s auto–motive theory (Chartrand & Bargh, 2002) proposes that goals are strongly associated with the people, objects, and contexts in which the person pursues them. This means that even subtle exposure to goal-related stimuli in the environment can automatically activate the goal and guide our behavior without our even knowing this is happening. For example, Sandy’s goal to improve her dancing skills is associated with, among other things, her dancing shoes. In a hurry one day, she runs by a store window in which those same shoes are displayed. Without her being aware of why, the goal of improving her dancing may be activated, making it more likely that Sandy will choose to rehearse rather than give in to the temptation to sit on the couch and watch TV.

Auto-motive theory

The theory that even subtle exposure to goal-related stimuli can automatically activate the goal and guide behavior.

Goals are also strongly associated with other people. From early childhood, we internalize the standards and values of our parents and the broader culture, and throughout adulthood these social influences are like internal voices that shape the goals we choose and how we pursue them. Perhaps your goal to achieve in school is linked to your mother, who has very high expectations for you, or your grandmother, who worked tirelessly despite hardship to help pay your college tuition. If this is the case, then being reminded of these individuals, even without your realizing it, might actually make you work harder to achieve the high expectations they have for you. In one test of this idea (Shah, 2003), participants were subliminally primed with the name of a significant other who, prior to the experiment, they reported had either high or low expectations of them. They were then asked to solve a series of anagrams, or word puzzles. Those primed with someone who had high expectations of them worked for almost twice as long on the task and ended up solving almost twice as many anagrams as those primed with someone who had low expectations of their academic performance (see also Fitzsimons & Bargh, 2003). This finding, and many others like it, demonstrates just how subtly other people can influence our behavior: Our mothers pester us even when we don’t realize we’re thinking of them!

Does this mean that goals are represented in our minds just like every other piece of knowledge? No, goals are unique because they send urgent messages to the ego to act. In fact, whereas simple bits of knowledge—like the fact that a typical golf ball has 336 dimples—tend to fade from your memory at a constant rate, goals continue to demand attention at a constant and, in some cases, increasing rate until the end state is attained (Lewin, 1936; McClelland et al., 1953). In fact, when goal-directed action is interrupted, memory of the goal and a state of tension remain strong until the goal is attained, a substitute goal is pursued, or the goal is completely abandoned (Lewin, 1927; Zeigarnik, 1938).

Defining Goals as Concrete or Abstract

There is an old story of a man who comes across three bricklayers busy at work. He asks the first bricklayer, “What are you doing?” and the bricklayer replies, “What does is look like I’m doing? I’m laying brick.” He comes to the second bricklayer and asks him, “What are you doing?” This man replies, “I’m building a wall.” Still somewhat unsatisfied, the man approaches the third bricklayer and repeats his question, to which the bricklayer replies, “I am building a cathedral.”

This story illustrates how the same action can take on different meaning depending on how it connects to goals. This idea is central to action identification theory (Vallacher & Wegner, 1987), which was introduced briefly in chapter 2. Action identification theory explains how people conceive of action—either their own or others’—in ways that range from very concrete to very abstract. As the story above illustrates, the three bricklayers conceive of their actions in different ways, ranging from the concrete level of stacking bricks layered with mortar to the more abstract end state of building a cathedral. One way to understand the differences in their responses is to realize that concrete conceptions specify how the action is accomplished, and more abstract conceptions specify why the action is performed. Thus, we can say that each bricklayer is building a wall by laying bricks (more concrete) and is doing so because he wants to build a cathedral (more abstract). Moreover, we refer to the organization of these representations as a hierarchy, because at each level of representation, we can either move up the hierarchy to broader, more comprehensive conceptions of a particular action, or down the hierarchy to increasingly concrete specifications of how the action is accomplished.

Action identification theory

The theory that explains how people conceive of action—their own or others’—in ways that range from very concrete to very abstract.

Action Identification Theory

Ever try eating Cheetos with chopsticks? Unless you’re accomplished at using these utensils, chances are the difficulty you encounter will lead you to consider the concrete goal of getting food into your mouth.

[Mark Landau]

Being able to identify our actions at different levels in the goal hierarchy is very handy. For example, when we run into difficulty in attaining an abstract goal, we can shift to a lower-level identification that allows us to focus more attention on specific concrete actions. This is demonstrated in a study (Wegner et al., 1983) in which American participants were asked to perform the fairly routine task of eating the cheesy snack known as Cheetos. However, although some participants were asked to eat the Cheetos in the usual manner (with their hands), other participants were asked to eat the Cheetos with a pair of chopsticks (see FIGURE 5.5).

For all but the most adept chopstick users, this presents some difficulty. (Chopsticks are certainly not the utensil of choice for most Americans who have the munchies.) Participants were then asked to describe what they were doing. Participants using their hands, who were not surprisingly performing the task rather well, were more likely to agree with fairly abstract definitions of their actions (e.g., “eating,” “reducing hunger”). However, participants using the chopsticks, who were having considerably more difficulty, were more likely to endorse concrete descriptions of their action (e.g., “chewing,” “putting food in my mouth”). When our action bogs down, we shift attention toward lower levels of abstraction, focusing on more concrete actions.

Although considering actions in concrete terms can be effective when we encounter problems, there are also benefits to interpreting actions at higher, more abstract levels of identification. For one, it provides a way for us to make sense of our experience with the world. For example, when you think that you are reading this textbook as one step in the larger endeavor of trying to complete your degree requirements, this helps to make sense of your (we hope not too dull) activity of staring at words on pages. And by making sense of the nitty-gritty details of our daily experience by framing them in terms of abstract goals, we also stay motivated to achieve those goals (Wegner et al., 1986).

The Benefits of Time Travel: The Role of Imagining the Future in Self-regulation

As you think about what courses to take, how much do you think about how interesting the topic is versus the amount of writing that will be involved? Do the factors that influence your decision differ if the course starts next week or next fall? According to Yaacov Trope and Nira Liberman’s construal level theory (Liberman & Trope, 1998; Trope & Liberman, 2003), when people imagine events in the distant future, they focus more on the abstract meaning of those events than on the concrete details. In contrast, when thinking about events in the near future, people focus more on the concrete details. Why? We tend to have more concrete information available for events that are closer in time. For example, you probably have more information about your entertainment options for this Saturday night than for a Saturday night three months from now. So we get accustomed to having details available for near-future events but only general, abstract ideas available for more distant future events. An association forms between concrete thinking and temporally close events and between abstract thinking and temporally distant events. This association then becomes part of your routine way of thinking about future events.

Construal level theory

The theory that people focus more on concrete details when thinking about the near future, but focus more on abstract meaning when thinking about the distant future.

Because temporal construal affects whether we focus on concrete or abstract features of future possibilities, it affects our decision making. When we are thinking about the short-run, pragmatic concerns such as ease of a task matter most. When we are thinking about the more distant future, more abstract concerns such as learning and growing as a person matter more. In one study supporting this hypothesis (Liberman & Trope, 1998), students expected to do an assignment either the next week or in nine weeks. In each case, they had to choose either a difficult but interesting assignment or an easy but uninteresting one. When thinking about next week, the students preferred the easy assignment. But when thinking about nine weeks from now, they preferred the interesting assignment.

The main point here is that when we judge what we want to do in the future, the factors that we consider vary depending on how far away that future event is. When it’s close, we’re more influenced by concrete details. When it’s farther off, we are more influenced by our understanding of how that event is connected to our long-term goals.

Another context where imagining future events shapes our thinking is when we predict how a course of action will make us feel. Imagine that Saturday night is approaching and you have two options: Are you going to check out that new band at the local club? Or are you going to the party at Maria’s house? You’ll probably base your plans on some mental calculation of whether you will have more fun at the club or at Maria’s. The same thought process lies behind your decisions about what college to attend, what car to buy, whom to date, or even whether to get Captain Crunch or Cookie Crisp cereal for breakfast: How will the different options available to you make you feel down the road? This is a sensible strategy insofar as your predictions or “forecasts” are accurate, but how accurate are they? Although our ability to project ourselves into the future greatly enhances our capacity to predict and control our lives, research on affective forecasting—predictions of our emotional reactions to potential future events—reveals that our forecasts are often off base, like those of a pretty lousy meteorologist (Wilson & Gilbert, 2005).

Affective forecasting

Predicting what one’s emotional reactions to potential future events will be.

Dunn, Wilson, and Gilbert (2003) studied the accuracy of affective forecasting by taking advantage of a unique, naturally occurring experiment that happens on campuses throughout the United States every year: the random assignment of students to dorms and other housing options. In the spring of their freshman year, the researchers presented college students with a list of dorm and housing options and asked the students to predict, before being randomly assigned to a housing location, how happy they would be if they were assigned to a desirable housing location or an undesirable housing location. As you might expect, students indicated that they would be much happier if they were assigned to one of the more desirable houses. However, one year later, students did not differ in their level of happiness. Their earlier predictions had been inaccurate. Students in the desirable houses had overestimated how happy they would be, and students in the undesirable houses overestimated how miserable they would be.

Why do these affective forecasting errors happen? One explanation is that we often overestimate the impact of a salient factor, such as where a given dorm is located on campus or how big the rooms are. In so doing, we don’t think about the other factors that might actually play a much larger role in our emotional lives, such as whom we are paired to room with or critical life events that could swamp any small inconvenience of geography (Schkade & Kahneman, 1998; Wilson et al., 2000).

Overestimating future negative reactions may stop us from taking chances for fear they might not work out. For example, we might not ask someone out because of the anticipated pain of being rebuffed. This is because when we forecast our affect, we tend to underestimate how successful we are at coping with negative emotions that arise. Whether we suffer a social slight or our favorite sports team loses an important game, we anticipate that the painful sting of these unpleasant events will be greater than it is and last longer than it does (e.g., Gilbert et al., 2004). Can we do anything to increase the accuracy of our affective forecasting? Asking people to think broadly about the future events that can influence their affective reactions, rather than narrowly on just one anticipated event, is a good place to start. For example, college football fans at the University of Virginia and Virginia Tech were asked to predict how happy they would be for a week after their team won or lost a game between the two schools (Wilson et al., 2000). A subset of these participants was also asked to make a diary planner of their upcoming week (the week after the game) and indicate how much time they would spend on different activities. Students who did not make a diary planner overestimated the duration of their happiness with a win and the extent of their misery with a loss. In contrast, students who had been asked to indicate their activities over the coming week did not commit this forecasting error. Instead, because they listed all the activities that would be keeping them busy, they were more aware of how these other events would make them feel, and as a result, minimized their focus on the outcome of the football game.