What Is Self-esteem, and Where Does It Come From?

Self–esteem is the level of positive feeling you have about yourself, the extent to which you value yourself. Self-esteem is generally thought of as a trait, a general attitude toward the self ranging from very positive to very negative. Researchers have developed a number of self-report measures to assess self-esteem in both children and adults (e.g., Coopersmith, 1967; Rosenberg, 1965). Using such measures in longitudinal studies, researchers have shown that self-esteem is fairly stable over a person’s life span (e.g., Trzesniewski et al., 2003).

Self-esteem

The level of positive feeling one has about oneself.

However, self-esteem can also be viewed as a state, a feeling about the self that can temporarily increase or decrease in positivity in response to changing circumstances, achievements, and setbacks. In other words, someone whose trait self-esteem is pretty low can still experience a temporary self-esteem boost after getting a good grade on a test or a compliment on her appearance. Similarly, someone with normally high trait self-esteem can experience a dip in state self-esteem after being denied a promotion or having his marriage fall apart.

The fact that self-esteem can remain stable as a trait but vary as a state indicates that a number of factors influence it. One source is genetics. The stability of trait self-esteem from childhood to adulthood suggests that our self-esteem may result in part from certain inherited personality traits or temperaments (Neiss et al., 2002). This stability also suggests that, as noted in chapter 5, the reflected appraisals and social comparisons we experience as children have a lasting impact on our sense of self-worth. Research supports this idea (Harter, 1998). All else being equal, a child who better lives up to the standards of value conveyed by her parents and others is likely to receive more positive reflected appraisals and more favorable social comparisons, and therefore have greater self-esteem.

Of course, these standards are often quite different, depending on the culture in which you are raised. As we saw in chapter 4, among the Trobriand Islanders, an important symbol of self-worth is how many yams a farmer can harvest, and on certain occasions, pile in front of his home to signify his status (Goldschmidt, 1990). This type of landscaping would not be much of a source of self-esteem in front of the typical American or European home; a Lexus or Mercedes in the driveway would more likely do the trick. Bases of self-esteem generally differ between individualistic cultures such as the United States, where displaying one’s personal qualities and accomplishments garners self-esteem, and more collectivistic cultures such as Japan, where displays of modesty and pleasing the family patriarch would better improve self-esteem (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Sedikides et al., 2003).

Cultures also prescribe different standards of value for individuals at different stages of development. For example, the characteristics and achievements that made you feel valuable in grade school are likely to be different from those that gave you self-esteem in high school, and those standards continue to change throughout adulthood. In addition, because cultural worldviews offer individuals multiple paths to feeling valuable and successful, individuals raised in the same culture are likely to stake their self-esteem on different types of activities.

Crocker and Wolfe (2001) studied these differences and found that whereas one person may seek self-esteem in being physically attractive, another person’s self-esteem may be tied to academic accomplishments. Other common contingencies are others’ approval, virtue, and God’s love. People’s overall opinion of themselves increases and decreases primarily in response to achievements and setbacks in the areas of life most important to them.

Maintaining and Defending Self-esteem

Imagine this is your first couple of weeks at a new university or college. A group of students is discussing what kind of music they like, and you want to join the conversation. But you’re nervous. Will they like you? How will you feel about yourself if they don’t? After a while, you decide to enter in the conversation and note your fondness for the long-out-of-style pop star Barry Manilow. A painful silence in the conversation follows. Your contribution is ignored by some and ridiculed by others. Wait until they hear about your enthusiasm for ice fishing!

Think ABOUT

As we navigate through our social worlds, we encounter a seemingly limitless cascade of challenges and events that can potentially threaten our sense of ourselves as a person of worth. Focus on yourself for a moment. What are the soft spots in your self-esteem armor? Of course, it’s never easy to admit or think about such things, but the more we understand about ourselves, ultimately the better off we are.

Some events pose a severe threat, for instance, losing one’s job or being dumped by one’s romantic partner. But there are also a number of other, much more minor events that can threaten self-esteem: an acquaintance on campus who doesn’t say “Hi!”; asking a dumb question in class; a friend noticing a piece of toilet paper stuck to the bottom of your shoe. How can we maintain self-esteem in light of all these potential threats? It turns out that people use many strategies to defend self-esteem and enhance it when possible. We’ll begin by considering strategies that focus on how we explain our own behavior and then progress to strategies that involve the self in relation to other people.

Self-serving Attributions

The self-serving attributional bias is to make external attributions for bad things that one does, but internal attributions for good things one does. In other words, people are quick to take credit for their successes and blame the situation for their failures (e.g., Snyder et al., 1976), a biased way of viewing reality that helps people maintain high levels of self-esteem (Fries & Frey, 1980; Gollwitzer et al., 1982; McCarrey et al., 1982).

What are the consequences of making self-serving attributions for our behavior? Some research suggests this bias helps support mental health. For example, self-serving attributions seem to work well for preserving self-esteem and are common among well-adjusted people. Individuals suffering from depression tend not to make self-serving attributions, viewing themselves as equally responsible for their successes and their failures (e.g., Alloy & Abramson, 1979). So some level of self-serving bias in attributions is probably useful for mental health (e.g., Taylor & Brown, 1988). However, this bias may interfere with an accurate understanding of poor outcomes. This is a problem because understanding the true causes of one’s poor outcomes is often very helpful in improving one’s outcomes in the future.

Self-handicapping

In a strategy known as self-handicapping, people set up excuses to protect their self-esteem from a failure that may happen in the future (Berglas & Jones, 1978). Suppose you decide to go out to a bar, stay out really late, and get wasted the night before an important exam. How would that be a preemptive strategy to protect your self-esteem? If you fail the test, you can say, “Well, it’s because I had this killer hangover from getting plastered the night before.” And if you happen to do well, this makes your success all the more remarkable. That way, even though you’re doing something to hinder (handicap) your own performance, you can attribute your failure to the excuse (e.g., partying) and not your own abilities. This strategy can keep your self-esteem intact, but it’s also very self-defeating because it makes poor performance more likely.

Self-handicapping

Placing obstacles in the way of one’s own success to protect self-esteem from a possible future failure.

When are people most likely to self-handicap? People self-handicap when they are especially focused on the implications of their performance for self-esteem rather than on getting the rewards associated with success (Greenberg et al., 1984). In addition, Berglas and Jones (1978) showed that self-handicapping stems from uncertainty about one’s competence. People who have experienced success in the past but are uncertain about whether they can succeed in the future are the most likely to self-handicap.

Self-handicapping has been used to explain a wide variety of behaviors in which individuals appear to sabotage their own success: abusing alcohol or other drugs, procrastinating, generating test anxiety, or not preparing for an exam or performance. Indeed, perhaps the most common form of self-handicapping is to simply not try one’s hardest on challenging tasks. If you don’t try your hardest, then you can attribute poor performance to a lack of effort rather than a lack of ability. Psychologists often attribute the lack of effort to low expectations of success, feelings of helplessness, or fear of success. But often instead what people are doing is self-handicapping. How do we know? When people who fear they will not succeed on a task are given a handy excuse should they fail (such as the presence of distracting music), they actually perform better (Snyder et al., 1981). The excuse reduces their concern with protecting their self-esteem, which frees them to put in their best effort.

Of course, not all people self-handicap to the same extent. Some individuals are generally more likely to self-handicap than others (Kimble & Hirt, 2005). There is evidence that men are more likely than women to self-handicap, suggesting that women place relatively higher value on effort (McCrea et al., 2008).

The Better Than Average Effect

Think for a moment about the percentage of the chores you do around your house or dorm. Then ask your roommate what percentage of the chores she thinks she does. We’re betting the total will well exceed 100% (Allison et al., 1989). This example illustrates how people often overestimate the frequency of their own good deeds relative to those of others (Epley & Dunning, 2000). In fact, as we described in chapter 5, the average person thinks that she or he is above average on most culturally valued characteristics and behaviors (Alicke, 1985; Taylor & Brown, 1988). Clearly, we can’t all be above average on these characteristics, so how do people maintain this perception that they’re superior? When people perform poorly on some task, they tend to overestimate how many other people also would perform poorly. This allows people to think they are better than average even on dimensions in which they don’t excel. In contrast, when people perform very well on a task, they tend to underestimate how many other people also would perform well. So people think their shortcomings are pretty common but their strengths are rather unique (Campbell, 1986).

Projection

Another way people avoid seeing themselves as having negative characteristics is to try to view others as possessing those traits which they fear they themselves possess. For example, if I fear that I’m overly hostile, I might be more likely to see others as hostile. Classic psychoanalytic psychologists such as Freud (1920/1955a), Anna Freud (1936/1966) and Carl Jung (Jung & von Franz, 1968) labeled this form of self-esteem defense projection.

Projection

Assigning to others those traits that people fear they possess themselves.

In one series of studies (Schimel et al., 2003), students were given personality feedback showing that they had high or low levels of a negative trait such as repressed hostility or dishonesty. Participants then read about a person, Donald, whose behavior was ambiguously hostile (or dishonest). Those participants given an opportunity to evaluate Donald saw him as possessing more of the trait they feared they might possess (e.g., hostility). Moreover, after evaluating Donald, they were less likely to think about the trait and saw themselves as having less of that trait than participants who were not given the opportunity to rate (and thus project onto) Donald. Because they saw the feared trait in someone else, they no longer feared that they had it!

Symbolic Self-completion

In the early 1900s, Alfred Adler noted that when people feel inferior in a valued domain of life—he called that feeling an inferiority complex—they often compensate by striving very hard to improve in that domain (Adler, 1964). This can be a very productive kind of compensation for one’s weaknesses. However, the theory of symbolic self-completion (Wicklund & Gollwitzer, 1982) suggests that people often compensate for their shortcomings in a shallower way. When people aspire to an important identity, such as lawyer or nurse, but are not there yet and worry they may not get there, they feel incomplete. To compensate for such feelings, they often acquire and display symbols that support their desired identity, even if those symbols are rather superficial.

Theory of symbolic self-completion

The idea that when people perceive that a self-defining aspect is threatened, they feel incomplete, and then try to compensate by acquiring and displaying symbols that support their desired self-definition.

Consider a woman who has always wanted to be a doctor, but then experiences some kind of setback, such as getting a poor MCAT score or making a mistaken diagnosis while interning. This poses a threat to her view of herself as an aspiring doctor, making her feel incomplete. She compensates by amassing symbols of competence as a premed, medical student, or doctor, perhaps prominently displaying her medical degree or wearing a lab coat and stethoscope around her neck whenever possible. In one study, male college students given feedback that they were not well suited for their career goals became very boastful regarding their relevant strengths—even when interacting with an attractive female student who they knew did not like boastful people (Gollwitzer & Wicklund, 1985). In contrast, people who are secure in their identity are more open to acknowledging their limitations and do not need to boast of their intentions or display symbols of their worth (Wicklund & Gollwitzer, 1982).

Recent research has focused on individuals who have just acquired a symbol of completeness. For instance, law students who were induced to state publicly their positive intention to study actually acted on this intention less often than students who were made to keep this intention private. Going public with their intention enhanced their symbolic completeness, thus ironically making further striving for their identity goal of becoming successful lawyers less necessary (Gollwitzer et al., 2009). This finding suggests a possible negative consequence of the growing trend of using social media to broadcast one’s progress toward goals by posting, for example, calories burned or books read. These symbols might give you a premature sense of having achieved your desired identity. As a result, you may neglect to take concrete steps toward fully achieving your identity goal.

Compensation

Early personality theorists such as Gardner Murphy and colleagues (Murphy et al., 1937) and Gordon Allport (1937) noted that people possess considerable flexibility in the way they maintain self-esteem. When self-esteem is threatened in one domain, people often shore up their overall sense of self-worth by inflating their value in an unrelated domain. This is called compensation, which essentially allows a person to think, “I may be lousy in this domain, but I rule in that other one” (Greenberg & Pyszczynski, 1985a). For example, when participants were given personality feedback that they were not very socially sensitive, they responded by viewing themselves more positively on unrelated traits (Baumeister & Jones, 1978).

Compensation

After a blow to self-esteem in one domain, people often shore up their overall sense of self-worth by bolstering how they think of themselves in an unrelated domain.

This idea has been further developed by Steele’s self-affirmation theory (Steele, 1988), which posits that people need to see themselves as having integrity and worth, but can do so in flexible ways. As a result, people respond less defensively to threats to one aspect of themselves if they bring to mind another valued aspect of themselves—that is, if they self-affirm.

Self-affirmation theory

The idea that people respond less defensively to threats to one aspect of themselves if they think about another valued aspect of themselves.

For example, college students participated in a study immediately after their intramural sports team either won or lost a game (Sherman et al., 2007). As you might expect from our previous discussion of self-serving attributions, players generally were more likely to attribute the outcome to their own performance when their team won than when they lost. However, players who had self-affirmed by writing about something else they valued did not make these self-serving attributions, taking equal responsibility for their team’s victory or defeat.

Self-affirmation also reduces people’s defensiveness when they are faced with threatening information about their health. For example, whereas smokers tend to respond to cigarette warning labels by denying the risk or downplaying their smoking habit (“I smoke only when I party”), these defensive responses are minimized if smokers first affirm core personal values or morals (Harris et al., 2007).

When people face a self-esteem threat, do they prefer to minimize it directly, by enhancing their standing on the valued self-aspect, or indirectly, by affirming an unrelated self-aspect? To find out, Stone and colleagues (1994) induced hypocrisy regarding practicing safe sex and then gave participants a choice of purchasing condoms or donating money to a homeless shelter. Although donating money allowed participants to affirm their overall worth, most of them (78%) chose to purchase condoms instead. Thus, although self-affirmation is a powerful strategy for indirectly minimizing self-esteem threats, people generally prefer to compensate for their shortcomings directly. Consistent with symbolic self-completion theory, this is especially true when the threat pertains to an important identity goal (Gollwitzer et al., 2013).

Social Comparison and Identification

In chapter 5, we noted that social comparison plays a substantial role in how people assess their own abilities and attributes. As a consequence, comparing ourselves with others who are superior to us leads to upward comparisons that can threaten self-esteem, whereas comparing ourselves with others who are inferior leads to downward comparisons that help us feel better about ourselves. Generally, people prefer to compare themselves with others a bit less accomplished than themselves, so comparisons can bolster their self-esteem (Wills, 1981). If you’re a moderately experienced tennis player, beating a similarly experienced friend in tennis in close matches feels better than either getting beaten by a pro or trouncing a novice.

Although people often prefer to compare themselves with others worse off, they also use a variant of this strategy when comparing themselves with, well, themselves. People tend to think they are much better in all respects now than they used to be, essentially engaging in downward comparison with their former selves (Wilson & Ross, 2001).

Although comparison with successful others can hurt self-esteem, affiliating with successful others can help bolster self esteem, an idea referred to as basking in reflected glory, or BIRGing (Cialdini et al., 1976). If you’re associated with an individual or group that is successful, then that reflects positively on you. Robert Cialdini and colleagues (1976) demonstrated this with regard to college sports. Research assistants systematically observed what students wore on campus the Monday following football games for a number of weeks. Students were more likely to wear school-affiliated apparel after a win than after a loss. Thus, students were more likely to display their university allegiance when that allegiance led to association with a successful team, and less likely to do so when that allegiance led to association with an unsuccessful team. Such reactions, moreover, are especially likely to occur after people experience a threat to their self-image.

Basking in reflected glory

Associating oneself with successful others to help bolster one’s own self-esteem.

Not sold on the BIRGing idea yet? Take, then, the fact that the teams with the best-selling sports apparel traditionally are the most successful. Over the past five years in the United States, gear for the New York Yankees, the Miami Heat, and the San Francisco 49ers has been very popular in national sales for baseball, basketball, and football, respectively. Not surprisingly, these are among the winningest teams in the last five years.

[Nick Laham/Getty Images]

Although research on BIRGing shows that people sometimes gain self-esteem by affiliating with very successful others, other evidence suggests that people could lose self-esteem by comparing themselves with more successful others. How can other people’s successes trigger opposite effects? Abe Tesser’s (1988) self-evaluation maintenance model proposes that people adjust how similar they think they are to successful others, both to minimize threatening comparisons and to maximize self-esteem-bolstering identifications. When another person outperforms you in a domain (or type of activity) that is important to your self-esteem, perceiving the other person as dissimilar makes comparison less appropriate. But when the domain is not relevant to your self-esteem, comparison is not threatening, so you can BIRG by seeing yourself as similar to the successful other. For example, a math major may feel threatened by comparison with the math department’s star student and so will distance from that person and see the math star as a very different person than herself. But the same person won’t be threatened by a star music student and may even derive self-esteem from affiliating with that person and focusing on their similarities.

Self-evaluation maintenance model

The idea that people adjust their perceived similarity to successful others to minimize threatening comparisons and maximize self-esteem-supporting identifications.

Closeness in age also affects self-evaluation maintenance in the context of sibling rivalry. In one study, Tesser (1980) examined relationships between brothers. They found that for males who had a more accomplished older brother, their relationship was more contentious the closer they were in age. Being farther apart in age makes comparisons less relevant, and so a younger male was likely to see himself as “just like my older brother” and could therefore gain self-esteem through identifying with him (BIRGing). When the brothers were closer in age (i.e., less than three years apart) comparison was more relevant. This self-esteem threat strained the relationship, leading to more perceptions of difference and more friction. So a key variable that determines whether people identify with or distance themselves from a successful other is whether comparison is or is not relevant. If it is relevant, people distance; if it is not, they identify. Amateur basketball players can safely admire and view themselves as generally similar to LeBron James, but if you were a fellow NBA All-Star, you’d be more likely to think you’re very different from him.

APPLICATION: An Example of Everyday Self-esteem Defenses—Andrea’s Day

|

APPLICATION: |

| An Example of Everyday Self-esteem Defenses—Andrea’s Day |

To summarize this section on self-esteem defenses, let’s consider how a fictional college student named Andrea might employ such defenses in a typical day.

Andrea wakes up and sends a text to her brother, telling him that her close friend Megan just won a poetry competition. “I don’t know anything about poetry,” she writes, “but I’m so proud of her!!” (basking in reflected glory).

Driving to work, Andrea is appalled at how bad drivers are in this town. “The majority of these people don’t have a clue about how to drive,” she tells herself (the better than average effect). She’s walking to class when her mother calls her and starts yelling about how Andrea forgot to call Grandma and wish her a happy birthday yesterday. Andrea yells back, “Well, I totally would’ve if you had just reminded me!!” and hangs up (self-serving attributions).

She still has some lingering doubts about her value as a granddaughter, but she reminds herself that her job right now is to do well in school (self-affirmation) and that she is an excellent student (compensation). After class, a friend approaches Andrea and asks if she wants to come to a free ballroom dance class that evening. She agrees to come but decides to work out at the gym that afternoon. Later, as they are walking to the studio, Andrea tells her friend how tired and sore she is from working out earlier (self-handicapping). Andrea is stunned to see what a good dancer her friend is, and just how much more graceful her friend is than Andrea could ever hope to be. Andrea then says to herself, “My friend and I are such different people. Dancing is her thing, not mine” (self-evaluation maintenance).

She leaves the class to meet up with her boyfriend for dinner. At one point during dinner, Andrea looks out of the restaurant window and notices a particularly attractive guy whom she’s admired a couple times. A moment later, she looks up and notices her boyfriend glancing at another woman. Instantly she starts berating her boyfriend about being loyal and keeping his eyes off other women (projection). That night Andrea loads her Facebook page with pictures of herself receiving an academic award and of her trips to Europe, so that everyone can see that she is educated and cosmopolitan (symbolic self-completion). She goes to bed, secure in the knowledge that she is a person of value.

Why Do People Need Self-esteem?

Given the wide range of ways that people defend their self-esteem, and the energy that they expend in doing so, why are people so driven to have high self-esteem? Do we just have an innate need to view ourselves positively? Perhaps, but our needs typically serve some function. The need for food serves the larger purpose of making sure that we get the nutrition we need for survival. But what purpose does self-esteem serve?

Self-esteem as an Anxiety-buffer

One answer to this question comes from the existential perspective of terror management theory. As we described in chapter 2, this theory starts with the idea that we humans are uniquely aware of the fact that our lives will inevitably end one day. Because this fact can create a great deal of anxiety, people are motivated to view themselves as more than merely material creatures who perish on death. According to terror management theory, this is precisely the function of self-esteem: to help the individual feel like an enduringly significant being who will continue in some way beyond death. In this way, self-esteem functions as an anxiety-buffer, protecting the individual from the anxiety stemming from the awareness of his or her mortality. The poet T. S. Eliot anticipated this idea in his eloquent ode on low self-esteem, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1917/1964, p. 14):

Anxiety-buffer

The idea that self-esteem allows people to face threats with their anxiety minimized.

I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker,

And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker,

And in short, I was afraid.

Self-esteem serves this anxiety-buffering function over the course of development. As children, we minimize our anxieties by being good, because if we are good, our parents love and protect us. As we develop and become more and more aware of our mortality and the limitations of our parents, we shift our primary source of protection from our parents to the culture at large. As adults, we therefore base our psychological security not on being good little girls or boys but on being valued citizens, lovers, group members, artists, doctors, lawyers, scientists, and so forth. We feel high self-esteem when we believe that we have or will accomplish things and fulfill roles our culture views as significant, that we are valued by the individuals and groups we cherish, and that we are making a lasting mark on the world. In this way we can maintain faith that we amount to more than mere biological creatures fated only to perish entirely.

If self-esteem protects people from death-related anxiety, then we would expect that when self-esteem is high, people will be less anxious. A large body of research examining the characteristics of high and low trait self-esteem people fits this hypothesis. Compared with those low in self-esteem, high-self-esteem people are generally less anxious; less susceptible to phobias, anxiety disorders, and death anxiety; and function better under stressful circumstances (e.g., Abdel-Khalek, 1998; Loo, 1984). However, because this evidence is correlational, there are many potential explanations. It may mean that high self-esteem buffers anxiety, but it also could mean that functioning well with minimal anxiety raises people’s self-esteem.

More compelling evidence that self-esteem buffers anxiety comes from experimental studies. In a study by Greenberg and colleagues (1992), half of the participants were randomly assigned to have their self-esteem boosted by receiving very positive feedback about their personality, supposedly based on questionnaires they had filled out a few weeks earlier; the other half were given more neutral personality feedback. Then participants watched a 10-minute video that was either neutral or depicted graphic scenes of death (excerpts from Faces of Death, Vol. 1; you might not want to watch these videos before going to bed—if ever!). Participants then reported how anxious they felt.

When the personality feedback was relatively neutral, participants reported feeling more anxiety after the threatening video than after the neutral video, as you might expect. However, if they had first received the positive personality feedback, participants who watched the threatening video did not report any more anxiety than those who watched the neutral video. The boost to self-esteem allowed them to be calm even in the face of gruesome reminders of mortality. Not only do people report less anxiety after a self-esteem boost, their bodies show fewer signs of stress. In one study, participants given self-esteem-boosting feedback showed reduced physiological arousal when they anticipated receiving electric shocks (Greenberg et al., 1992). Self-esteem accomplishes this anxiety-buffering by increasing activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, which helps to calm people and control their anxiety (Martens et al., 2008).

Another way to assess this function of self-esteem is to find out if reminding people of their own mortality leads them to strive even harder to bolster their self-esteem and to defend it against threats. In the first direct tests of this hypothesis, Israeli soldiers who reported that they either did or did not derive self-esteem from their driving ability were reminded of their mortality or not. They were then placed in a driving simulator and asked about their likelihood of engaging in risky driving behaviors on the road (Ben-Ari et al., 1999). Now, you might expect that thinking about your mortality would make you a more cautious driver, right? But this reasoning misses an important point of terror management theory, namely, that to shield ourselves from the fear of death, we strive to feel valuable. Consistent with this idea, when first reminded of their mortality, those participants who derived self-esteem from their driving ability drove especially fast and claimed they would take more driving risks when out on the road. Additional studies have shown that mortality salience also increases strivings in other self-esteem-relevant domains, such as physical and intellectual performance and displays of generosity (see Greenberg & Arndt, 2012).

If self-esteem shields us from our fear of death, then our shield should be weakened when our self-esteem is threatened, making us more likely to think about death. Across a series of studies, Hayes and colleagues (2008) found that when participants experienced a threat to their self-esteem, thoughts of death became more accessible to consciousness. In sum, a substantial body of converging evidence indicates that self-esteem provides protection from basic fears and anxieties about vulnerability and mortality.

Social Functions of Self-esteem

Our awareness of our human vulnerability and mortality is one driving force behind our striving for self-esteem. Two other perspectives place special emphasis on the social aspects of self-esteem.

First, Jerome Barkow (1989) proposed that people desire self-esteem to maximize their social status, just as monkeys try to maximize their position in a dominance hierarchy. Barkow proposed that those of our ancestors who were most focused on seeking high social status had the most access to fertile mates and resources to nurture their offspring, therefore perpetuating their genes into future generations. To the extent that desiring self-esteem serves attaining high social status, this desire would have been selected for over the course of hominid evolution.

Sociometer model

The idea that a basic function of self-esteem is to indicate to the individual how much he or she is accepted by other people.

Think ABOUT

Second, according to Mark Leary and colleagues’ (1995) sociometer model, a basic function of self-esteem is to indicate to the individual how much he or she is accepted by other people. According to this model, self-esteem is like the gas gauge in your car. The gas gauge is a meter that lets you know when the gas is too low and you need to fill up. Similarly, according to the model, self-esteem is like a sociometer that lets you know if you are currently receiving the social acceptance you need to satisfy a need to belong. Consequently, the more you perceive yourself to be liked and accepted by others, the higher your level of self-esteem. According to the sociometer model, when people appear to be motivated to maintain self-esteem, they actually are motivated to feel a sense of belongingness with others. Although both Barkow’s status-maximizing perspective and Leary and Baumeister’s sociometer model emphasize the social functions of self-esteem, the former emphasizes the desire to stand out and be better than others, whereas the latter emphasizes fitting in with and gaining the acceptance of others. Each perspective captures something true about self-esteem. Barkow’s analysis can help explain why people often sacrifice being liked in order to be successful and gain status, whereas the sociometer model can help explain why people sometimes sacrifice status and material gain in order to fit in with the group. However, both perspectives have difficulty explaining why people are so likely to bias their judgments to preserve their self-esteem. For example, people often feel they are more worthy than other people think they are. If self-esteem were primarily an indicator of something of evolutionary value, such as social status or belonging, rather than something that buffers anxiety, why do people seem to distort their beliefs to inflate their views of themselves? It would be akin to moving the gas gauge with your fingers to convince yourself you had gas in your tank when you actually did not. Does this disconfirm the sociometer model? Or is there some way to reconcile the model or revise it to fit with the research on self-esteem defenses?

Types of Self-esteem

Think ABOUT

Up to this point, we have been talking about self-esteem as if it were a unitary construct. But is this really the case? If two people both report having high self-esteem, does this mean their feelings of worth actually are the same? Early theorists such as Karen Horney (1937) and Carl Rogers (1961) suggested that the answer is no. They pointed out that some people have more secure, authentic feelings of positive self-regard, whereas others may report the same high self-regard but are actually compensating for feelings of inferiority. Furthermore, for some people, self-esteem is durable, but for others, it fluctuates from day to day. Take a moment to think about how you feel about yourself. Is your self-esteem generally the same as it was yesterday? And the day before that?

Mike Kernis and colleagues measured self-esteem stability by looking at how much people’s responses to self-esteem measures changed over the course of a week (e.g., Kernis & Waschull, 1995). They found that self-esteem stability has a number of consequences even when people are equally high in overall levels of self-esteem. People whose self-esteem is more unstable tend to be sensitive to potential threats to their self-esteem. For example, when an acquaintance doesn’t return a greeting, a person with unstable self-esteem is likely to be offended and concerned about his broader social reputation, whereas a person with stable self-esteem is more likely to ignore the same event (Kernis et al., 1998).

Why are certain feelings of self-esteem more unstable than others? One important factor is where we get our self-esteem from. As we noted previously, self-esteem can be derived from a variety of sources. Some sources, such physical appearance, are extrinsic because they provide self-esteem when we meet standards dictated by the external environment. Other sources are intrinsic because they connect feelings of self-esteem to inner qualities that seem more enduring. As a result, when people rely on extrinsic sources, their self-esteem is contingent on feedback from others. Because this feedback can vary in favorability, they have less confidence in their overall value. In contrast, when people base their self-esteem on intrinsic qualities, their feelings of value are less contingent on others’ feedback. Research has found that participants reminded of extrinsic sources of self-esteem, such as social approval or personal achievements, make more downward social comparisons, are more likely to conform to the opinions of others, and are more likely to engage in self-handicapping than participants led to think about intrinsic qualities of themselves (Arndt et al., 2002; Schimel et al., 2001).

Researchers have often assumed that self-esteem is a conscious attitude about oneself, but emerging research suggests it can also be an unconscious attitude. Various methods have been developed for tapping into unconscious feelings about the self (e.g., Bosson et al., 2000). In one study, implicit self-esteem was measured as the speed at which participants could identify words such as good (as opposed to bad) after being primed with first-person pronouns such as I, me, and myself (as opposed to neutral primes) (Spalding & Hardin, 1999). Interestingly, these implicit signs of self-esteem are only weakly correlated with people’s explicit feelings about themselves. So people’s levels of explicitly reported self-esteem and implicit self-esteem are often quite different. This suggests that people can consciously report that they think they are great and have many worthwhile qualities, whereas deep inside they might harbor negative associations with their self-concept. Research suggests that this type of person is most likely to have unstable self-esteem and to exhibit narcissistic tendencies and defensive responding (Jordan et al., 2003).

APPLICATION: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Self-esteem

|

APPLICATION: |

| The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Self-esteem |

So far we have discussed what self-esteem is, the sources of self-esteem, the many ways we maintain and defend it, and why people need self-esteem. Let’s now consider four important implications of this knowledge.

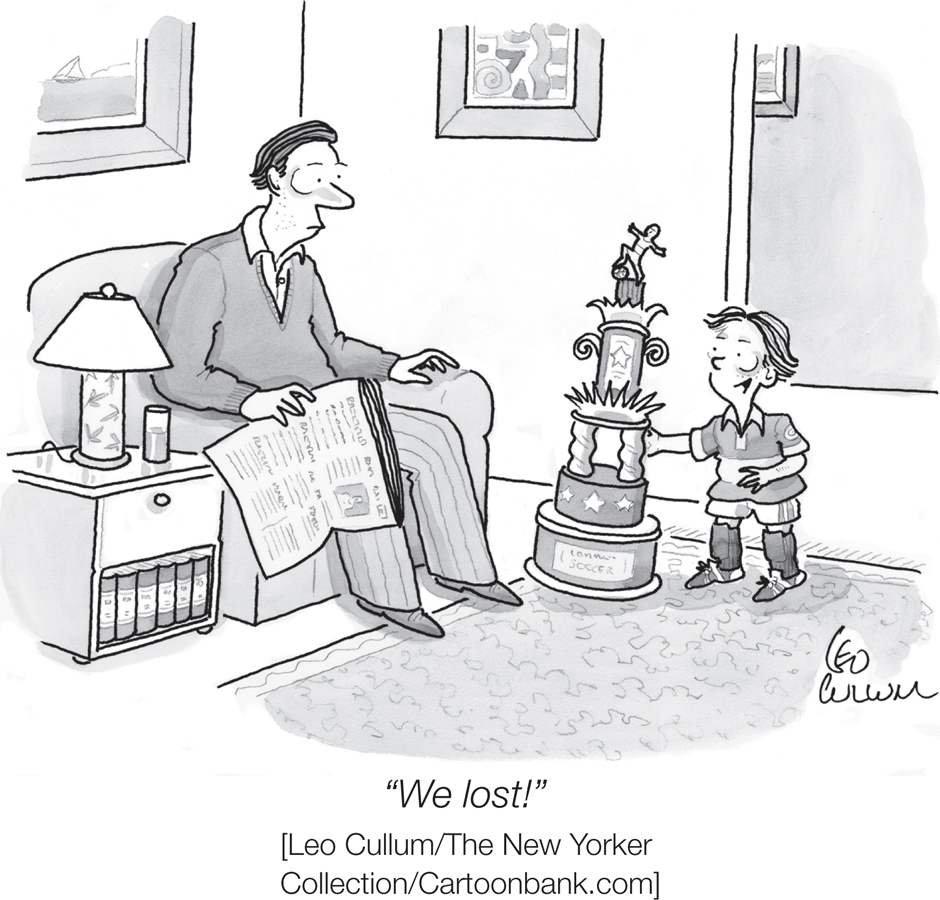

Self-esteem cannot be easily granted to people. Children must internalize a meaningful worldview and clear standards for being a good and competent, and therefore valued, person. Then they must learn how to self-regulate to meet those standards of value and continue to meet them so that their value is validated throughout the life span. So school programs that give every kid a gold star and youth soccer leagues that give every player a trophy are not helping to instill secure, enduring self-esteem. And in adulthood, simply telling someone else or yourself, “You are a good, worthy person” won’t do the trick either (e.g., Greenwald et al., 1991). Instead, meeting socially validated standards of self-worth provides the best basis of stable self-esteem, the kind of self-worth that best serves people’s psychological needs.

-

People with either unstable self-esteem or low self-esteem will struggle with psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, and drug dependencies, which often result from attempts to avoid or alleviate these negative psychological feelings. Such people are also likely to lash out at others, to express hostility, and even to resort to physical aggression. Research has clearly linked narcissism and borderline personality disorder, two psychological profiles in which unstable self-esteem and low self-esteem are prominent, to various forms of aggression (e.g., Bushman & Baumeister, 1998; Kernis et al., 1989; Salmivalli et al., 1999). The same message can be found by examining dramatic examples of school shootings, such as those at Columbine (1999) and Virginia Tech (2007). Those who engage in them often seem to be lashing out at specific people or the world in general because they do not feel valued.

People pursue self-esteem in ways that fit with their cultural worldview, sometimes with harmful consequences. Self-esteem pursuit often takes the form of trying to do good by eradicating evil in the world. Depending on one’s worldview, this can lead to noble actions or ignoble ones. Those who focus on poverty or disease as evil often pursue self-esteem by helping the poor or dedicating their lives to fighting diseases such as cancer. In one study, those who reported deriving self-esteem from being altruistic were the most likely to help a stranger who they believed had been injured (Wilson, 1976).

But other people try to do good by eradicating individuals or groups they perceive to be evil, leading to aggression. Hard as it may be for Americans to believe, the people who committed the suicidal terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001 did so because they thought it was the right thing to do and would prove their value. In fact, while those who commit such acts are referred to by Americans as terrorists or suicide bombers, they are often viewed as heroic martyrs by their supporters in Islamic countries. The typical Islamic suicide bomber seeks significance and eternal life in paradise by attacking evil in the name of Allah. Believing in a very different worldview, Americans have sought their own heroism by fighting in wars against symbols of evil such as Hitler, communism, and Saddam Hussein.

Striving for self-esteem can have constructive or destructive consequences for the self. For instance, young American women are socialized to derive considerable self-value from their appearance. This emphasis can lead to extreme dieting, restrictive eating, and ultimately anorexia (Geller et al., 1998). On the other hand, to the extent that the culture promotes the value of an athletic, healthy body for young women, more positive health consequences of self-esteem striving could result. Similarly, self-esteem striving will have destructive consequences for young people who are encouraged to gain self-worth through risky behaviors such as reckless driving, fighting, binge drinking, and drug use. Indeed, depending on what society defines as valuable, and the extent to which people are sensitive to these social definitions, mortality salience seems to encourage risky behaviors such as restrictive eating and excessive tanning, but also healthy behaviors such as quitting smoking (e.g., Arndt & Goldenberg, 2011). Self-esteem striving also leads people to engage in various defenses that interfere with their having an accurate view of themselves. This can lead them to choose career paths they are not suited to and to repeat mistakes rather than recognize weaknesses and work toward improving them. When people are particularly lacking in self-esteem or feel it is threatened, they are especially likely to avoid potentially useful diagnostic information about themselves (e.g., Sedikides & Strube, 1997; Strube & Roemmele, 1985).

Because self-esteem striving can be detrimental in some ways, researchers (e.g., Crocker & Park, 2004) have wondered whether people can simply stop caring about their self-worth. But the theories and research we have reviewed suggest this is both undesirable and unlikely. First, striving for personal value often leads to accomplishments that contribute positively to society. Second, if we accept the idea that self-esteem is a vital buffer against anxiety, then if we were stripped of self-worth, we would be unable to function. In this light it might not be too surprising that in societies with limited culturally embraced avenues for self-worth, we see high levels of clinical depression and dependence on chemical mood enhancers (e.g., Kirsch, 2010; Swendsen & Merikangas, 2000). We’ve seen the most extreme consequences of losing all sense of socially validated value with mass killings in places such as Columbine High School and Virginia Tech. Perhaps the best we can hope for is to fashion, both individually and as a society, more constructive avenues for self-esteem, open to all, without hurting others so as to lift ourselves up (e.g., Becker, 1971).

Another possibility is to cultivate self-compassion, an idea developed from Buddhist psychology (Brach, 2003; Neff, 2011). Compassion involves being sensitive to others’ suffering and desiring to help them in some way. You feel it, for example, when you stop to consider your friend’s struggle with a painful experience. Rather than judge or criticize her, you look for ways to provide comfort and care. You practice self-compassion when you take the stance of a compassionate other toward the self.

Self-compassion

Being kind to ourselves when we suffer, fail, or feel inadequate, recognizing that imperfection is part of the human condition, and accepting rather than denying negative feelings about ourselves.

Self-compassion involves three elements. The first is self-kindness. When faced with painful situations or when confronting your mistakes and shortcomings, your tendency might be to beat yourself up, but with self-compassion you would respond with the same kindness toward the self that you would show to a close other. The second element is the recognition that everyone fails or makes mistakes on occasion, and that suffering and imperfection are part of the shared human experience. The third element, mindfulness, means accepting negative thoughts and emotions as they are rather than suppressing or denying them.

Self-compassion lessens the impact of negative life events and is linked to psychological well-being, including more optimism, curiosity, and creativity, and less anxiety and depression (Hollis-Walker & Colosimo, 2011; Leary et al., 2007; MacBeth & Gumley, 2012). Most of this research has used trait measures of self-compassion, but other researchers also have developed ways to increase self-compassion and look at the effects of doing so. In one study (Shapira & Mongrain, 2010), a group of volunteers wrote a self-compassionate letter to themselves every day for a week; another group wrote letters about personal memories. The self-compassion group showed higher levels of happiness as much as six months later.

Self-compassion offers a way to maintain stable high self-esteem even though you make mistakes and sometimes fall short of your own standards and goals and other people’s expectations for you. This healthier approach to maintaining self-worth should make it less dependent on self-serving biases and defensiveness. By cultivating self-compassion, people can maintain self-esteem even if they fail and without having to view themselves as superior to others (e.g., Neff & Vonk, 2009).