6.3 Self-presentation: The Show Must Go On

Alan: I think we live our lives so afraid to be seen as weak that we die perhaps without ever having been seen at all. Denny, do you ever worry that when you die, people will never have truly known you?

Denny: I don’t want them to know me, I want them to believe my version.

David E. Kelley (2008), Boston Legal, “Tabloid Nation” April 8, 2008

We’ve been focusing primarily on the individual’s private view of her or his own self, but the self is as much a public entity as it is a private one. Life casts people into different social roles (child, student, patient) that are part of their cultural worldview, but those people also help create their own public personas. In fact, the word personality derives from the Greek word persona, a word originally used to describe the masks that Greek actors wore on stage to represent their characters’ current emotional state.

The Dramaturgical Perspective

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.”

William Shakespeare (English playwright, 1564–

In books such as The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959), the sociologist Erving Goffman offered a dramaturgical perspective that uses the theater as a metaphor to understand how people behave in everyday social interactions. From this perspective, every social interaction involves self-

Dramaturgical perspective

Using the theater as a metaphor, the idea that people, like actors, perform according to a script. If we all know the script and play our parts well, then like a successful play, our social interactions flow smoothly and seem meaningful, and each actor benefits.

Virtuoso Joshua Bell playing a three-

[Michael Williamson/The Washington Post/Getty Images]

People learn their scripts and roles over the course of socialization. Parents, teachers, and the media teach children about weddings, funerals, school, parties, dates, concerts, wars, and so forth, long before they experience any of these things firsthand. Kids also learn how to be friends, teammates, students, and romantic partners. They play at various culturally valued adult roles such as astronaut, athlete, mother, doctor, teacher, or pop star. As a result of these and other socialization experiences, in every social situation there is a working consensus, an implicit agreement about who plays which role and how it should be played.

The social context defines a person’s role, fellow performers, and audience. The power of the situation to define roles, perceptions, and behavior was vividly demonstrated when, in 2007, the Washington Post journalist Gene Weingarten persuaded the internationally acclaimed violinist Joshua Bell to play for nearly an hour in a crowded Washington, DC Metro station. Three nights earlier, in the impressive setting of a sold-

217

Sincere versus Cynical Performances

Many of the situations people encounter are so familiar that they are not consciously aware that they’re playing a role or following a script. In a classroom, for instance, you automatically take on the student role. Goffman refers to these well-

Sometimes meeting new people or being in an unfamiliar environment can be uncomfortable, if not downright painful. The premise of the Meet the Parents movies is based on this very idea of cynical performance. Consciously trying to play a role is never easy, yet we’re forced to do it far more often than we’d probably like.

[Universal/Photofest]

In contrast to sincere performances, cynical performances are conscious attempts to perform in a certain way to make a particular impression. People are more likely to engage in such performances when they find themselves in unfamiliar territory or when they want to convey a specific impression. Think back to your first day of college. You probably did a lot of preparation, thinking about what to expect, how to dress, and so on. When you arrived, you were probably fairly self-

Are people always performing? Goffman would say yes. Even when you wish to be most genuine—

Self-presentational Strategies

Honing an Image

Jones and Pittman (1982) described some common strategies we use to meet our self-

Audience Segregation

In their everyday lives, people have to stay in character to uphold a particular public identity with a given audience. Goffman pointed out that people do so in part by keeping different audiences segregated so that they can perform consistently with each audience. If you have ever worked in a restaurant, you’d know that wait staff act very differently in the kitchen than they do out on the floor.

Goffman (1959) pointed out that waiters have to work hard to perform in a deferential and pleasant manner to their audience, the restaurant customers. Because of the strain behaving in this manner creates, they often act very differently backstage in the kitchen area. The 2005 film Waiting humorously portrays this phenomenon, as exemplified here by waitress Naomi (played by Alanna Ubach), who exudes charm and patience out front with the customers but rage and contempt when back in the kitchen.

[Jeff Greenberg]

Similarly, at the mall with your parents, you’d probably rather not run into your friends. Your style of speaking, the words you use, the way you dress, and even your body posture are likely to be different when you’re with your parents than when you’re with your friends. How do you give two different performances at once? Faced with such a multiple audience problem, sometimes people use different communication channels to convey different self-

218

Lying

One fundamental goal in self-

Because of the importance of protecting face, people often bend the truth. For example, you may assure someone that his presentation went well when in fact it put you to sleep. This perspective suggests that lying is pretty common and often motivated by the need to protect face—

Think ABOUT

The participants lied about twice a day and lied to 38% of the people they interacted with over the week. Three quarters of the lies were about face-

219

APPLICATION: The Unforeseen Consequences of Self-presentation

|

APPLICATION: |

| The Unforeseen Consequences of Self- |

Sometimes it’s difficult to determine if we’re doing what we want or doing what everyone else wants us to do. Take this person, for example. How much is he really wanting to be held upside down in the midst of a large crowd to drink beer from a tap? How much is he conforming to the idea of a crazy beach party? And how much is he caving to the pressure of the group? It’s often very difficult, if not impossible, to tell, but clearly people’s concerns with self-

[Sean Murphy/Getty Images]

In 2011, among high school students who were sexually active, about 40% reported not using a condom during their last sexual encounter (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Why? One reason is that many people report feeling embarrassed when they buy condoms (Bell, 2009). Those who do have condoms sometimes feel that it might make the wrong impression if they suggest using one during sex (Herold, 1981). These concerns about the impression you are making on a drugstore cashier or a one-

Unsafe sex isn’t the only risky health behavior that people might adopt for the sake of making a good impression. Those who are more concerned about the impression they make on others are also more likely to put themselves at risk for skin cancer in order to perfect their tans (Leary & Jones, 1993); use or abuse drugs and alcohol as a way to fit in with the “right” crowd (Farber et al., 1980; Lindquist et al., 1979); or engage in unhealthy dieting practices or steroid use to achieve that perfect body (Leary et al., 1994). Studies show that women eat less in front of an attractive man (Pliner & Chaiken, 1990) and when they want to present a more feminine impression (Mori et al., 1987). Based on these lines of research, interventions (e.g., for sun protection or smoking cessation) are starting to focus more on image-

Individual Differences in Self-presentation

At this point you might be thinking, “Wow, I can really see how much I self-

Self-monitoring

An individual difference in people’s desire and ability to adjust their self-

People who are high in self-

Audience-monitoring Errors

Does careful self-

Spotlight effect

The belief that others are more focused on us than they actually are.

Singer/songwriter Barry Manilow performing in the 1970s.

[Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images]

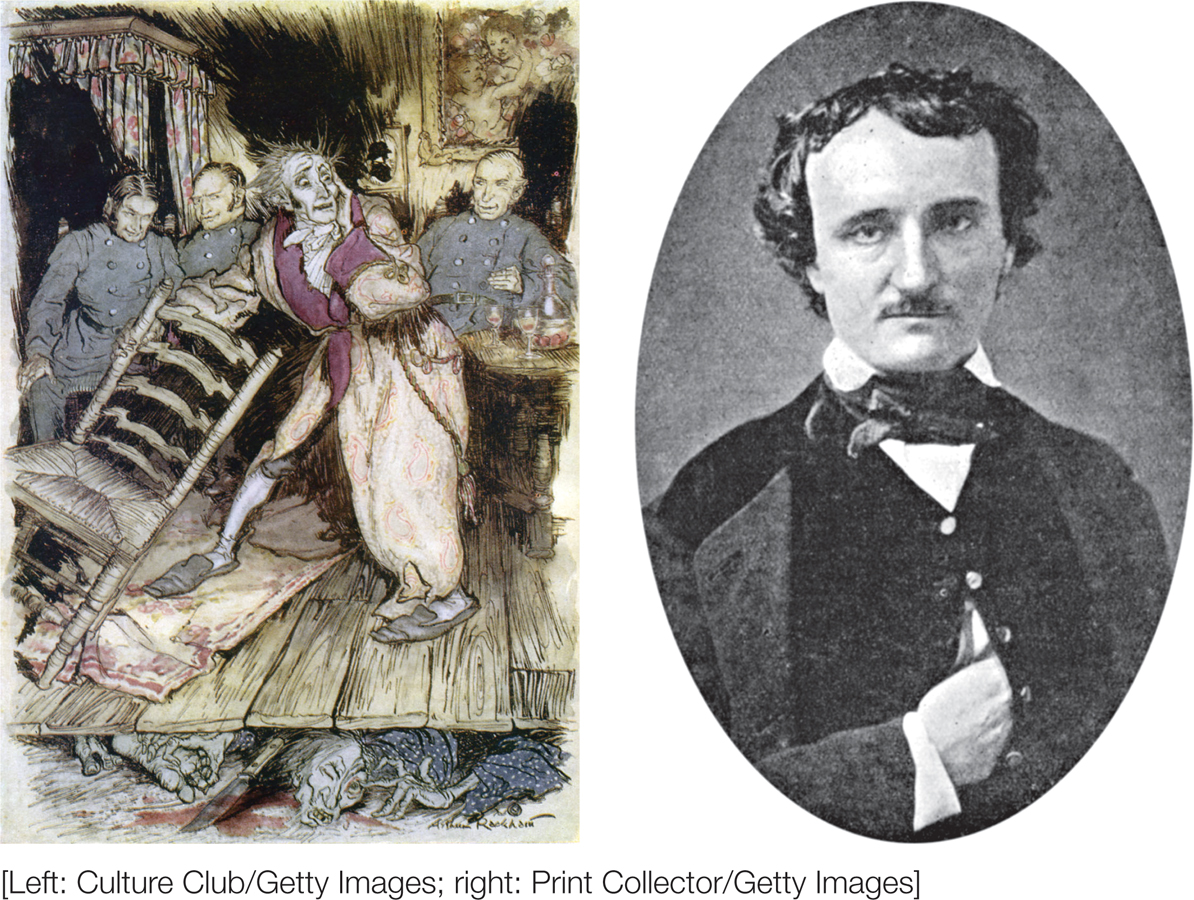

A chilling portrayal of the illusion of transparency can be found in Edgar Alan Poe’s classic short story “The Tell-

[Left: Culture Club/Getty Images; right: Print Collector/Getty Images]

220

Such egocentric bias doesn’t just lead people to mistake whether others notice aspects of their external appearance. It also leads people to overestimate others’ ability to know their internal thoughts and feelings. Imagine a situation where you smile politely as you choke down bite after bite of a friend’s new, but decidedly vile, recipe. Many of us imagine that our disgust is laid out on the table for everyone to see. According to Gilovich, Savitsky, and Medvec (1998), this is probably only an illusion of transparency, because people are often better than they think they are at hiding their internal feelings. This is something to keep in mind the next time you get nervous about giving a speech or doing something in public. In fact, even when peopie rate themselves as being a jittery ball of nerves, those who observe their speech often rate them as appearing less anxious (Savitsky & Gilovich, 2003).

Illusion of transparency

The tendency to overestimate another’s ability to know our internal thoughts and feelings.

The Fundamental Motivations for Self-presentation

Why is self-

221

|

Self- |

|

People are motivated to manage how others view them. |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Theater as a metaphor

|

Self-

|

Application Concerns about making certain impressions can lead to unhealthful behaviors. |

Self-

|

Basic motives for self-

|