8.2 Characteristics of the Source

President Barack Obama claims that he can be persuaded equally by Democrats and Republicans if the ideas are good. Research on persuasion suggests that it is often not that simple.

[Photothek via Getty Images]

“What’s most important is: what gets the job done…. I don’t think that the Democratic Party has a monopoly on good ideas. I think that the Republicans have a lot to offer. And what I will do is listen and learn from my Republican colleagues, and any time they can make a case that this is something that would be good for the American people, just because Democrats didn’t think of it, and Republicans are promoting it, that’s not a good reason not to do it. If somebody presents to me a plan that they are ideologically wedded to, but they can’t persuade me that this will actually be good for the economy, then we’re not going to do it.”

President-

278

Communicator Credibility

Messages are especially persuasive when they are delivered by a person (or a group) perceived to have source credibility—that is, someone who is both expert and trustworthy. Consider a study by Hovland and Weiss (1951). Participants read articles that advocated various positions on different issues. For example, one article advocated that antihistamine drugs should be sold without a doctor’s prescription. Half the participants were told the article was from the New England Journal of Biology and Medicine (an expert source), whereas the others were told it came from a popular magazine such as those you see in the supermarket (a nonexpert source). As you might expect, participants were more likely to agree with the position advocated in the articles if they thought the articles came from expert sources rather than nonexpert sources (Pornpitakpan, 2004).

Source credibility

The degree to which the audience perceives a message’s source as expert and trustworthy.

Although real expertise can convey strong arguments that persuade people through central-

The source of a message can also gain credibility by being perceived as trustworthy or unbiased in his or her views. Most of us are aware that other people typically have something to gain from changing our attitudes, and so we often are skeptical about whether they are telling the whole truth and nothing but the truth. In fact, if people are forewarned that another person intends to persuade them about issues they care about, they are less convinced by that person’s arguments (Petty & Cacioppo, 1979).

How can the source of a persuasive message come across as trustworthy? One way is to express an opinion without the audience realizing that it is the target of persuasion. Imagine that you overhear some people at a coffee shop praising a new restaurant. You have no reason to believe that these people are biasing their opinions to influence you (they don’t even know you’re eavesdropping!), and so you might find their opinions more believable. In a study testing this intuition, Walster and Festinger (1962) arranged a situation so that participants were allowed to overhear a conversation between two graduate students in another room. (In actuality, they heard an audio recording.) Some participants were under the impression that the graduate students were aware that they were in the next room, whereas other participants assumed that their presence was unknown to the graduate students. Participants in the second group was more likely to change their attitudes in the direction of the graduate students’ opinions, presumably because they had no reason to believe that the graduate students were purposely altering what they said.

The power of overheard messages hasn’t been lost on advertisers. Just think of all the commercials you’ve seen that attempt to portray a private conversation between two people (“Gee, Tyler, your glasses really do sparkle! What dish detergent do you use?”). In fact, advertising and public relations agencies often pay writers to masquerade online as delighted consumers, writing positive reviews of their products or services on various web sites such as Amazon.com (Dellarocas, 2006). The writers are paid to appear like average people, for example by intentionally inserting typos into their reviews. In this way, advertisers hope that the fake reviewers appear trustworthy, and thus persuasive, because the writers do not seem to have a stake in the sale of the product or service.

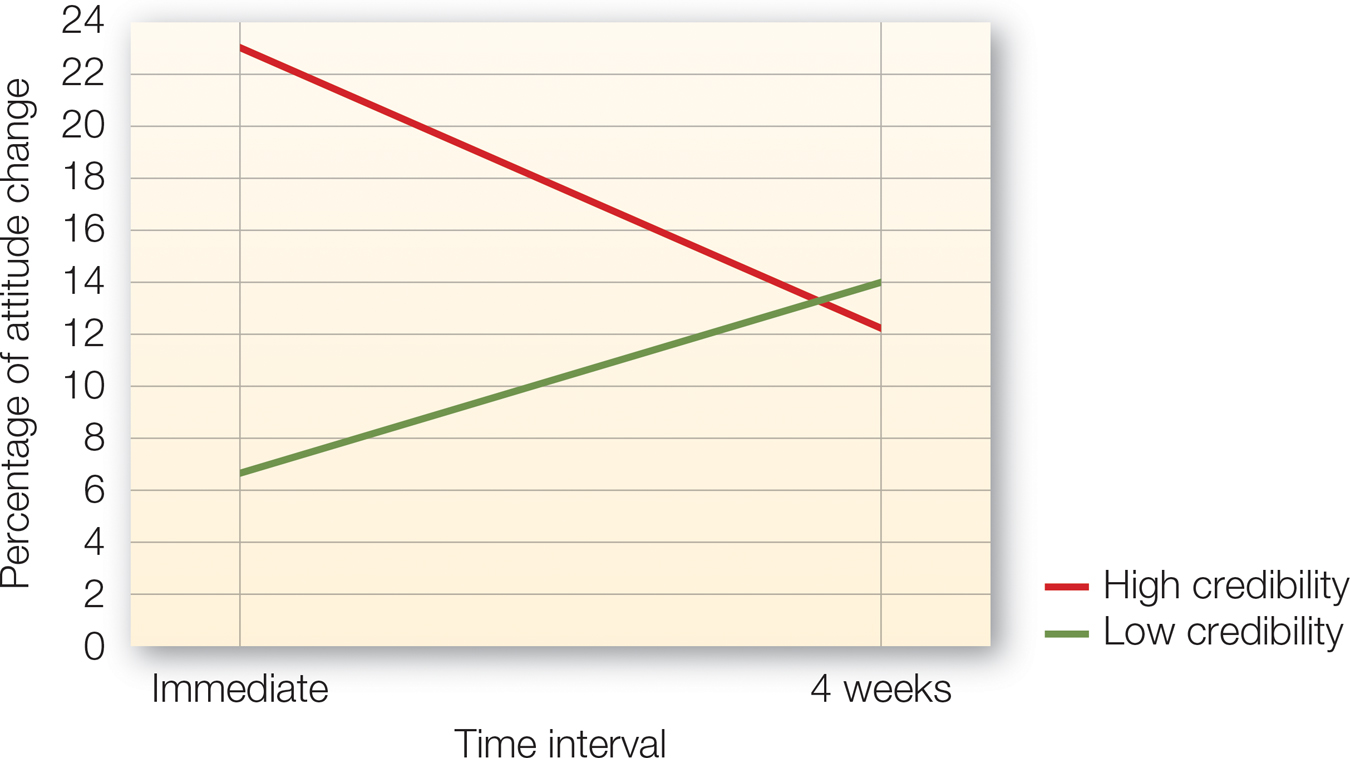

FIGURE 8.4

The Sleeper Effect

In this study, people were more likely to change their attitude to agree with arguments if the author was an expert and therefore credible. But 4 weeks later, the credibility of the source no longer mattered, and arguments made by less credible sources were equally likely to have changed people’s minds.

[Data source: Hovland & Weiss (1951)]

279

Another way in which a communicator gains in trustworthiness (and persuasiveness) is if he or she argues in favor of a position that seems to be opposed to his or her self-

Credibility can be a peripheral cue when people are not elaborating on the persuasive message. It’s a handy heuristic simply to decide, “She’s an unbiased expert, I’ll believe that,” or “I’m not buying anything that sleazeball says.” However, this kind of peripheral influence of source credibility may not last long. The decay of source effects can happen when over time, people forget the source of the message but remember the message content, a concept known as the sleeper effect. Suppose that you scan the front page of a sensationalistic gossip magazine while waiting on the grocery checkout line (come on, we all do it at least occasionally), and it claims that new evidence calls global warming into question. A few weeks later, the topic of global warming comes up in a conversation, and you remark that you read a story arguing that global warming may in fact not be happening, but you can’t remember where you read it. Might that argument be more compelling now that you’ve forgotten that it came from a not-

Sleeper effect

The phenomenon whereby people can remember a message but forget where it came from; thus, source credibility has a diminishing effect on attitudes over time.

Hovland and Weiss (1951) found the first evidence of the sleeper effect. Recall the experiment showing that people were more likely to agree with high-

Communicator Attractiveness

Your current author recently saw a commercial in which the actor Dennis Haysbert recommended buying insurance from Allstate Insurance Company. In this context, Haysbert is not particularly high in credibility. First, although he may be an expert actor, having appeared in many movies and television series (e.g., he played the president of the United States in the popular TV show 24), who knows whether or not he has expert knowledge of the relative merits of different insurance companies? Second, his trustworthiness is in doubt: It is obvious that Allstate is paying him handsomely to appear in these commercials and that he is trying to influence us. So why is Haysbert considered an effective spokesman? If you’ve seen the commercials, you probably know the answer: He just seems like a likeable and straightforward guy. He is handsome and well dressed, and he looks straight at you as he asks you in his authoritative baritone voice whether you are in “good hands.” This example suggests that communicators can be persuasive when they are attractive, even if their credibility is low.

280

The most obvious way that a communicator gains in attractiveness is by presenting an attractive physical appearance. Certainly you’ve noticed how magazines, billboards, and pretty much every other commercial medium features attractive models (some of which are computer-

Think ABOUT

When the communicator’s attractiveness is irrelevant to the true merits of the position he or she takes, as when a supermodel graces a billboard for an energy drink, it influences the audience’s attitudes through the peripheral route. It is important to note, though, that the communicator’s attractiveness also can influence attitudes through the central route when it is an argument for the validity of the message (Shavitt et al., 1994). Consider an attractive, muscled spokesperson for a rather odd-

Communicator Similarity

If we tend to be persuaded by those who are trustworthy, likeable, and attractive, we must also be more persuaded by people who are similar to us, right? Here the answer is a bit more complicated. In some cases, people are more easily persuaded when the source of a message is similar to themselves. In one study (Mackie et al., 1990), college students were more likely to agree with rather extreme positions (e.g., to discontinue use of the SATs in college admissions) if those positions were endorsed by a student from their own university, but not from another university.

Sometimes, however, people are influenced more by the opinions of dissimilar others than those of similar others. The key factor is whether the issue at hand deals primarily with subjective preference or objective facts (Goethals & Nelson, 1973). For issues dealing primarily with subjective preference—

In contrast, when people are trying to determine whether something is objectively true or factual, their attitudes are influenced more by the opinions of dissimilar others than by those of similar others. For instance, if you believe that Beyoncé sold more albums than Rihanna (which is either factually correct or incorrect), agreement from a dissimilar other would make you more confident in that belief than agreement from a similar other. Why? When similar others agree with us on matters of fact, we are often uncertain whether they agree simply because they like us, or perhaps because they have been exposed to the same faulty information that we have been exposed to. But when a dissimilar other who does not have those biases verifies our belief, we assume that the belief must be objectively true. (In case you were wondering, at least when it comes to studio albums, Beyoncé has sold more albums than Rihanna.)

281

|

Characteristics of the Source |

|

The power of a message to influence attitudes depends, in part, on who is delivering that message, or its source. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Credibility |

Attractiveness |

Similarity |

|

Credible communicators are both expert and trustworthy. Legitimate expertise persuades through the central route. The appearance of expertise persuades through the peripheral route. |

Communicators can be persuasive when they are attractive, even if their credibility is low. |

Attitudes about subjective preferences are influenced more by a similar source than by a dissimilar source. Attitudes about objective facts are more influenced by a dissimilar source. |