9.2 Why Do People Join and Identify With Groups?

Think ABOUT

For the better part of human history, the groups into which people were born—

Fortunately, most group memberships are not ascribed. If you are reading this textbook, chances are you have the opportunity to join any number of intramural sports teams and social clubs, committees, religious groups, and political parties. You can even move up the career ladder to join a higher social class. Of course, joining groups such as these also requires time and effort, and in some cases, entails stressful initiations and perhaps the loss of individual freedoms.

Why do people identify with groups that they are arbitrarily born into? And why join groups at all, given the commitments and personal sacrifices involved?

Promoting Survival and Achieving Goals

One answer to these questions is that belonging to groups has been crucial to the development and survival of humans as a species. Over the course of evolution, humans survived because they relied on social networks to acquire and share food, transmit information, rear children, and avoid predators and other threats (Brewer & Caporael, 2006). Within this environment, individuals with characteristics that helped them to get along with others—

This evolutionary perspective on group living suggests that people will almost always identify strongly with the family and cultural groups in which they were raised. People form close bonds within kinship groups, and with non-

People also form and join groups to accomplish goals that they would be unlikely to accomplish on their own (Sherif, 1966). Most human achievements—

Reducing Uncertainty

Life is filled with uncertainties, from the location of your keys to the content of next week’s physics exam. People generally dislike being uncertain about themselves. Nor do they like being uncertain about who other people are and how they might behave. According to uncertainty-

Uncertainty-identity theory

The theory that people join and identify with groups in order to reduce negative feelings of uncertainty about themselves and others.

315

How does belonging to groups reduce uncertainty? Groups reinforce people’s faith in their cultural worldview and their valued place within it. Most core beliefs can never be proven through personal experience. Even scientific facts—

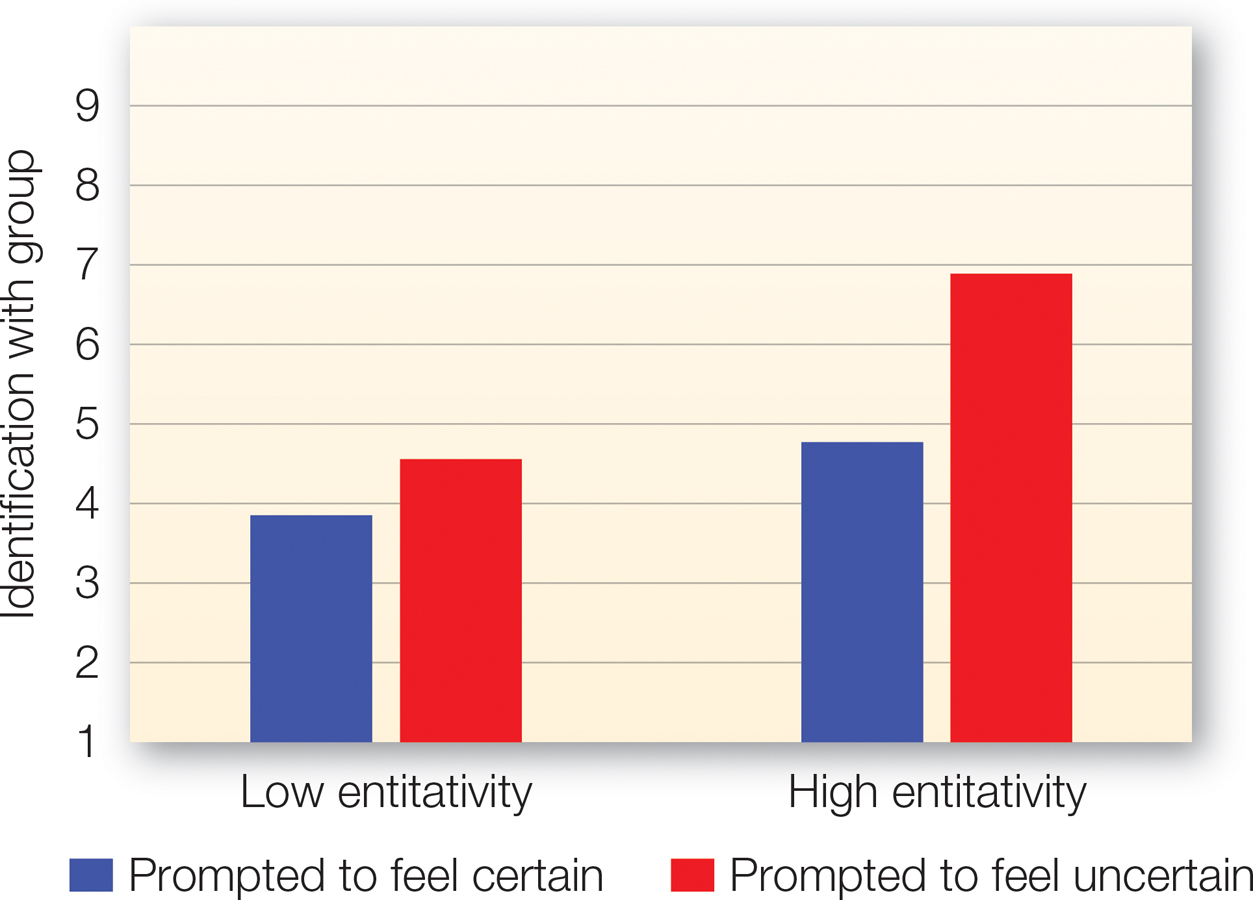

FIGURE 9.1

Group Identification Reduces Uncertainty

When participants were made to feel uncertain about themselves, they identified more strongly with a new group that was high in entitativity.

[Data source: Hogg et al. (2007)]

A second way groups reduce uncertainty is by prescribing norms and roles. As we discussed in chapter 2, norms are rules for how all members of a group ought to think and behave. Most norms are unspoken agreements about what behavior is acceptable or unacceptable, but they can also be expressed formally, as when some deadheads handed out flyers instructing concertgoers to “stay cool.” Whereas norms dictate how all group members should behave, roles are expectations for people in certain positions. When you are eating at a restaurant, you obey a norm against shouting or yelling loudly, but your server has a unique role that allows him to walk off with your credit card, even though you cannot walk off with his.

Norms and roles reduce uncertainty by providing clear guidelines for how people should think and act. As a result, people don’t need to think too hard about how to conduct themselves from one situation to the next. When people feel especially uncertain about who they are, uncertainty-

To test this hypothesis, Hogg and colleagues (Hogg et al., 2007) formed small groups of participants who did not previously know each other. Half of the participants were told that they and the other members of their group had all responded very similarly on a series of questionnaires and that their group was very different from other groups. In other words, they learned that their group was high in entitativity. The other participants were told that there wasn’t much similarity in how the members of their group had responded, and that all the groups were fairly similar to each other. This information should have made their group seem low in entitativity.

Think ABOUT

Then, in what seemed to be an unrelated task, half the participants were asked to write about ways in which they felt uncertain about themselves, their lives, and their future, while the other half of the participants wrote about aspects of their life that made them feel certain. Finally, all of the participants were asked how much they identified with the group that they had just become part of in the study. As the researchers predicted, increasing uncertainty about the self increased group identification, but only when the group was high in entitativity (see FIGURE 9.1). If you think back to when you first started college or university, did you quickly identify with a new group in order to manage the uncertainty of such a major life transition?

316

In addition to reducing uncertainty about oneself, norms and roles also reduce uncertainty about other people by making their behavior seem orderly and predictable. For example, groups usually have a norm of cooperating and agreeing with the other members of the group (Turner & Oakes, 1989). So even if you know nothing about an individual, if you know what groups she belongs to, you can expect her to behave in line with those groups’ norms and roles. For example, after reading the introduction to this chapter, you may have a reasonably clear expectation of how a deadhead would act. Of course, as we will see later, such generalizations and stereotypes can also lead to errors in judgment.

Bolstering Self-esteem

According to social identity theory, belonging to groups is an important source of self-

Social identity theory

The theory that group identities are an important part of self-

Ingroup bias

A tendency to favor groups we belong to more than those that we don’t.

Think ABOUT

If groups are a source of self-

People also enhance their self-

Managing Mortality Concerns

As you’ll recall from the discussion in chapter 2 on the existential perspective in social psychology, people need to cope with the threatening knowledge of their mortality. They do so by clinging to two psychological resources: faith in a cultural worldview and a sense of self-

317

|

Why Do People Join and Identify With Groups? |

|

People are born into some groups and join others voluntarily. People strongly identify with both types of groups. Here is why: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Promoting survival and achieving goals During human evolution, group cooperation benefitted survival and reproduction. Hence, modern humans have an innate desire to belong to groups. |

Reducing uncertainty People dislike feeling uncertain about themselves and others. Belonging to a group reduces negative feelings of uncertainty. |

Bolstering self- Groups are a source of self- By viewing their group in a positive light, people feel better about themselves. |

Managing mortality concerns Groups connect people to something bigger and longer lasting than their own existence. Hence, belonging to a group eases mortality concerns. |