9.3 Cooperation in Groups

The fantastic ability of humans to cooperate with each other is everywhere we look. Just marvel at how far human beings have come from their evolutionary beginnings to the construction of complex civilizations. In your own experience, your food, shelter, clothing, and physical safety, not to mention roads, electric power, waste management, intricate electronics, mass transit systems, institutions of higher education, and social welfare programs are all available to you thanks to the cooperation of many people. What’s more, the big challenges facing humanity today boil down to problems of group cooperation: How do conflicting groups come to trust each other? How can groups with competing interests make compromises and reach agreements?

Social Dilemmas and the Science of Cooperation

Because cooperation is critical for groups to develop trade and build economic relationships, the psychological study of cooperation and trust is often carried out by researchers interested in behavioral economics and decision making. The method used in this research is to have participants make a decision so that researchers can measure how they weigh their own self-

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

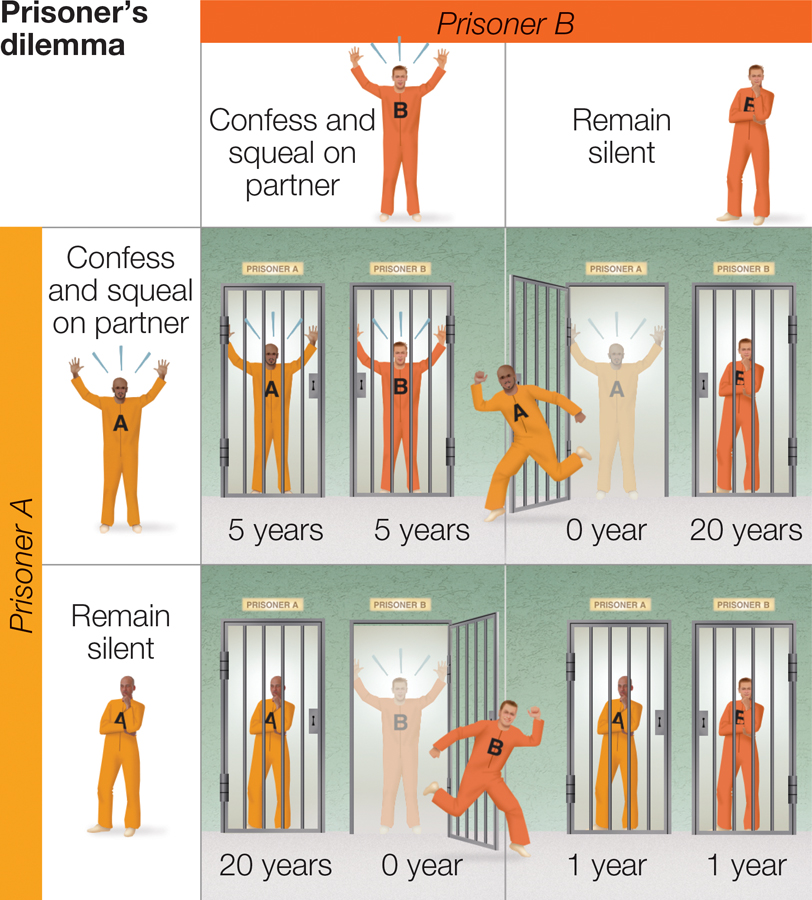

FIGURE 9.2

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

In the Prisoner’s Dilemma, you decide between cooperating and competing with a partner. Your decision depends on how much you trust your partner to cooperate with you.

The best known social dilemma is the Prisoner’s Dilemma, modeled after a scene you’ve probably seen played out on countless television law dramas. FIGURE 9.2 depicts a typical setup. You and your partner have been apprehended after committing a burglary and hiding your loot. The detectives are interrogating the two of you in separate rooms. They know you did the crime, but they need to build their case. You are offered a lighter charge if you confess to the heist and rat on your friend. The dilemma is that you know that your partner is being offered the same deal. If you both remain silent (i.e., cooperate with one another), the prosecution’s case will be flimsy, and you’ll both get light sentences. But the best-

318

When people are paired with partners to play this game over a series of trials, they often end up adopting a tit-

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

When Cooperation Is the Key to Economic Growth and Stability

When Cooperation Is the Key to Economic Growth and Stability

Have you ever stopped to consider how the money we use is itself a form of cooperation? If you didn’t agree to the value of your nation’s currency, any purchase you made would involve an intense debate over the value of the $5.00 bill you are offering in exchange for a sandwich. Not only is it an act of cooperation to agree on the value of currency, it also can be an act of cooperation to defend it. Two national case studies make these points clear.

First, consider the case of Barbados, a former British colony. During the early 1990s, Barbados experienced an economic crisis that threatened to cripple the country. One proposed solution was to devalue the Barbadian currency, just as neighboring Jamaica had done in 1978. But the government refused and instead used persuasion techniques such as appealing to national pride to orchestrate cooperation among employers, labor unions, and the workers themselves.

The result was that employees agreed to accept a onetime 9% reduction in their wages, and businesses agreed to keep price increases at a minimum while the economy weathered the storm and began growing again (Henry & Miller, 2009). Everyone took a temporary hit to their own economic self-

In the case of Barbados, people would not have been willing to sacrifice their own personal self-

Twenty years ago, Brazil faced its own economic crisis. After decades of printing money, inflation skyrocketed in the early 1990s. Imagine that one day you could buy a carton of eggs for $1.00, but by the end of the year a carton of eggs would cost you $1,000.00! The rate of inflation was so high that shopkeepers increased the prices of their goods every single day. As a result, people lost all trust in their government and in the value of their currency. As you know by now, trust is the key to cooperation.

How did Brazil turn its economy around so that today it is poised to become a global leader? A group of economists formulated a scheme to create a new currency that everyone could believe in. This new currency initially existed only as a name—

As these two stories make clear, people can cooperate both in belief and in behavior. Trust is the linchpin to making cooperation succeed. In both examples, though, people also were cooperating with others who shared a common national identity. Their identification with their country and its currency as a symbol of cultural value might also have played a role in fostering cooperation.

Earlier in this chapter, we discussed four factors that motivate people to identify with their groups: achieving goals, reducing uncertainty, bolstering self-

319

At the heart of the prisoner’s dilemma is a very basic decision. Can I trust you or can’t I? If I can’t, I’d better protect myself by defecting. Once distrust is there, both sides compete with each other. This is how nations racing to have the largest armed force and weapons stockpiles end up finding it difficult to strike a new, more cooperative pact for disarmament.

Resource Dilemmas

Taxes may be a pain, but they pay for many valued public resources that depend on everyone’s chipping in.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a scenario in which the outcome of a decision is interdependent with the choices that others make. Other social dilemmas involve competition for scarce resources. One resource dilemma is called the commons dilemma. The term commons comes from medieval times, when people would bring their herds to the town commons to graze (Hardin, 1968). Although it was in everyone’s self-

320

Another type of resource dilemma is called the public goods dilemma. A valued resource can continue to exist only if everyone contributes something to it. Local blood banks, libraries, and public radio and television are all examples of public goods that endure only because enough people chip in to keep them going. Solving a public goods dilemma requires cooperation of contributions so that the resource can be maintained. Indeed, taxes are society’s solution to this dilemma: Although you might not like to see those taxes come out of your weekly paycheck, they do help pay for the roads you drive on, the schooling you have received, and the parks where you vacation.

In both kinds of resource dilemmas, beware of free riders. These are individuals who take more than their fair share from the common pool or refuse to contribute to the public good, even while enjoying the same benefits. Free riders serve their own self-

Distribution Games

Researchers also study cooperation by looking at how people behave when faced with distribution games. These are called games because they involve somewhat artificial situations, yet they are not frivolous: They reveal the fundamental psychological processes by which people make cooperative decisions in their everyday lives. Distribution games are set up so that one person or group has the power to decide how resources get distributed. In the ultimatum game, one person (the decider) is given a real sum of money and told that she can decide how much to keep and how much to give to another person. The other person (the recipient) then chooses to either accept or reject this offer; but if the recipient rejects the offer, no one gets money. Researchers can look at whether people are more or less likely to distribute outcomes equally. The dictator game is similar, except that the recipient doesn’t have the option of “punishing” the decision maker by rejecting his or her sum. This allows researchers to look at people’s reactions to unfair distribution of resources.

In both games, people often distribute money equally, even though it clearly would be in their self-

When and Why Do People Cooperate?

These dilemmas and games allow researchers to study cooperation in its essence: How do people decide between what’s good for other people (cooperation) and what’s good for themselves (competition)? A number of factors nudge people toward either cooperation or competition. One factor is the norm that is salient in the person’s immediate context. When a prisoner’s dilemma was labeled the “Community Game,” participants chose to cooperate on twice the number of trials than when the same dilemma was called the “Wall Street Game” (Liberman et al., 2004).

In fact, very subtle contextual cues can make a difference, although these cues often interact with people’s personalities. In one study, subliminal primes of competition cued more competitive behavior in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, but only among participants who generally were high in competitiveness (Neuberg, 1988). There are also interesting interactions between people’s own dispositions and how their partner plays the game (Kuhlman & Marshello, 1975). Highly competitive people consistently defect regardless of the strategy their partners adopt, but highly cooperative people conform to their partner’s strategy by cooperating when he cooperates, but defecting if he defects. This means that when a consistently competitive person plays with a cooperative person, competitive strategies rule the day.

321

Culture also plays a role in cooperative tendencies. On the surface, it might seem that individuals from collectivist cultures would generally be more cooperative. After all, what better way to achieve social harmony than through cooperation? The full picture is more complex. People from collectivist cultures do cooperate more than those from individualist cultures, but only when they are interacting with friends (Leung, 1988); when interacting with strangers, collectivists can actually be more competitive. We see this in studies that prime different cultural identities. When Chinese Americans are primed to think about their Chinese identity (rather than their American identity), they become more cooperative when playing with friends but not with strangers (Wong & Hong, 2005). To sum up, cooperative tendencies might be more or less accessible for some individuals than others, but these dispositions are also cued by who you are with and what’s going on around you.

After considering factors that influence when people cooperate, we might wonder why people cooperate. Some researchers have addressed this issue by studying the neurocognitive and physiological processes that are triggered when people make decisions about social dilemmas. One line of research looks at the biological basis of trust, a prerequisite for cooperation. The hormone oxytocin is a biological marker of a range of prosocial behaviors including caregiving, social attachment, love, and trust (Porges, 1998). When other people place their trust in you, your levels of oxytocin rise and increase your willingness to act in a trustworthy way (Zak et al., 2005). Perceiving more trust also increases oxytocin levels, greasing the wheels of further trust and cooperation.

You can see oxytocin at work in a study by Kosfeld and colleagues (Kosfeld et al., 2005). Participants were randomly assigned to receive an injection of either oxytocin or a placebo. They then played the trust game, in which they decided how much money they wanted to invest with another player (called the trustee). The experimenter tripled whatever was invested, but much as in the dictator game, the trustee got to decide how much of that money she would pay back to the investor. Those who had received the boost in oxytocin were twice as likely to make the maximum investment as the placebo group.

People are not, however, blindly controlled by biochemical secretions. If the social basis for trusting others is absent, as when an interaction partner appears unreliable, an induced oxytocin boost does not increase trust (Mikolajczak et al., 2010). Oxytocin seems to signal that others are trustworthy, but it does not simply make people more gullible.

If trust influences people’s tendency to be fair, what about their reactions to being treated unfairly? Take away a child’s toy on the playground, and you will get a clear taste of an immediate, negative, and not to mention loud reaction to unfairness. We get a quieter indication of this negative reaction in neuroimaging studies. When people receive low offers in the ultimatum game, scans reveal activation in the anterior insula region of the brain, which is associated with an automatic emotional response. But people in these situations also exhibit increased activation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which suggests an additional cognitive deliberative response (Sanfey et al., 2003). By revealing the role of emotions, these findings contradict traditional views that decision making is a purely rational process. But they also show that when people reject an unfair offer, they override an initial impulse to take anything profitable that comes their way. In fact, if people’s right dorsolateral prefrontal context is temporarily deactivated, they become more likely to accept unfair offers, even while acknowledging that they are getting the short end of the stick (Knoch et al., 2006).

322

Fairness Norms: Evolutionary and Cultural Perspectives

When the TV talk show host Jimmy Kimmel asked parents to videotape their children’s reactions to learning that Mom or Dad had eaten all their Halloween candy, the resulting videos show people’s extreme emotional reactions when others violate their trust.

The consistent evidence of cooperation in decision-

Cooperation and fairness also have a strong cultural component. As we mentioned earlier, people sometimes reject offers in the ultimatum game even at a cost to themselves. By punishing these unfair offers, people enforce broader cultural norms of fairness. If this reaction were part of a biological adaptation, we might expect to see it across cultures and in our closest genetic nonhuman relatives. In fact, when chimpanzees play a version of the ultimatum game and one partner makes an unfair offer, the recipient will hiss and spit at the other chimp even while grudgingly accepting it (Proctor et al., 2013). Just like a child who is told by a parent that all the Halloween candy is gone, these close primate relatives express their outrage at having been shortchanged.

However, other research reveals that human norms of fairness vary across cultures. In large-

In tuna we trust. Large-

At first glance, you might think that small-

At the other end of the spectrum, historical factors that erode the development of trust can also curtail economic development. Nathan Nunn (2008), an economist at Harvard, has observed that those African countries that were most affected by the slave trade have seen the least amount of economic development and also exhibit the lowest levels of trust (Nunn & Wantchekon, 2011). His theory is that because people in former African slave-

323

|

Cooperation in Groups |

|

To survive and thrive, individuals in a group must cooperate, balancing their personal interests with others’ interests. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Studying cooperation The Prisoner’s Dilemma demonstrates how distrust escalates competition. Resource dilemmas demonstrate how cooperation is essential to providing or maintaining valuable shared resources. Distribution games assess whether people distribute resources fairly or unfairly and others’ reactions to those decisions. |

Cooperation: when and why Social norms, personality traits, and culture all play roles in determining when people will cooperate. Oxytocin signals trust. We respond negatively to unfairness. |

Evolution and culture A desire for fairness and cooperation are evolved characteristics. Norms of fairness are also promoted by cultures, although in varying ways. |