9.4 Performance in a Social Context

So far, we’ve explained the benefits of living in groups and the cooperation needed to navigate group life. But group living also means performing actions in the presence of or alongside others. If you are like most students, you probably groan at the thought of group projects or having to give a speech to the class. If humans evolved to live in groups, why does having to perform in a group seem so unpleasant and inefficient? In this section, we explore the effects that the social context can have on performance.

Performing in Front of Others: Social Facilitation

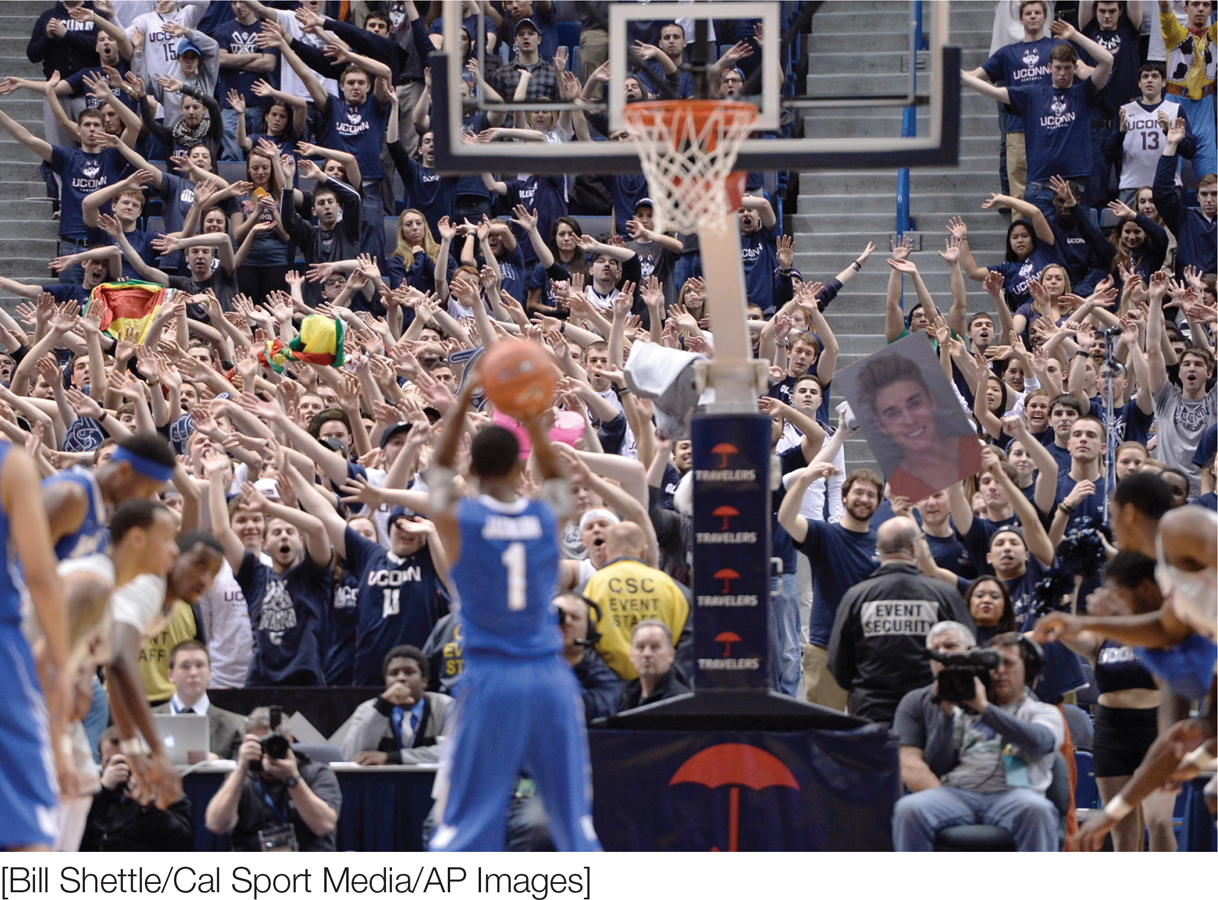

Athletes have to learn to perform in front of huge crowds, but sometimes even the best players and teams can choke under pressure.

It was 2008, and the NCAA men’s basketball championship trophy was on the line. With just under 2 minutes left to play, the Memphis Tigers had a 9-

The history of studying this and related phenomena goes back to the very beginning of social psychology and the first social psychology experiment ever published. However, this first study was concerned not with how performance is impaired by the presence of others, but with how performance can be improved by the presence of others.

Social Facilitation Theory, Take 1: When Others Facilitate Performance

At the end of the 19th century, Norman Triplett did what most professional psychology researchers do best. He observed a phenomenon in the world, developed a theory that he thought might explain it, and went about designing experiments to test his idea. The observation was that cyclists were able to ride 20 to 30 seconds per mile faster when they were racing with other cyclists than when they were racing alone in time trials. Triplett wondered if the mere presence of other competitors helps stimulate arousal that facilitates performance.

324

To test his idea, Triplett asked children to reel in a cord on a fishing rod as fast as they could. Sometimes they performed this task alone, with Triplett recording their time. Sometimes they competed with each other. In support of this early version of social facilitation theory, the majority of the kids tested were faster at reeling in the cord when they were competing than when they were performing alone (Triplett, 1898).

Triplett’s paper sparked a flurry of research exploring how an individual’s performance is affected not only by a competitive environment, but also by the mere presence of other people watching. Many studies showed that performance is facilitated when an audience is watching. The problem was that other studies began showing the opposite effect—

Social Facilitation Theory, Take 2: Others Facilitate One’s Dominant Response

Zajonc (1965) refined social facilitation theory by suggesting that the mere presence of others does not facilitate performance but rather facilitates one’s dominant response, that is, the response that is most likely for that person for that particular task. If that task is a simple motor task (reeling in a fishing line) or something that you’ve practiced very well (playing a piano sonata for the thousandth time), your dominant or automatic response is to reel fast and play accurately. In these cases, having an audience likely will enhance your performance. But if the task is a complex one (finding the logical inconsistencies in a classic philosophic text) or that you are only just beginning to learn (playing a piano sonata for the first time), the dominant response will be to make mistakes; therefore, an audience will most likely impair your performance. What is it about an audience that facilitates the dominant response?

Social facilitation theory

The theory that the presence of others increases a person’s dominant response in a performance situation—

The Role of Arousal

FIGURE 9.3

Do Other Species Get Aroused by an Audience?

Even cockroaches exhibit a social facilitation effect. They run an easy maze faster with other cockroaches present, but run a difficult maze more slowly with other cockroaches present, compared with when they ran the mazes in isolation.

[Research from: Visualization of Mazes used by Zajonc et al. (1969)]

Zajonc thought the effect of having an audience was the byproduct of a very basic innate arousal mechanism whereby all animal species—

Just as others had found with humans, when the task was easy, the cockroaches reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches than when they were alone. But when the task was hard, it took the cockroaches longer to reach their goal with other cockroaches lurking about. Because the psychology of a cockroach is pretty stripped down compared with our own, these findings suggest that very basic biological processes of arousal activated in the presence of others are partly responsible for social facilitation effects.

325

However, human psychology is more complex than cockroach psychology. Modern research reveals that the type of arousal that humans feel in the presence of others also depends on their interpretation of the situation. In chapter 6 we introduced the idea that a person’s reaction to a stressful situation depends on whether she feels she has the resources to meet the demands of the task she faces (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996). When a person believes she has the necessary resources, perhaps because she is performing a well-

Let’s return to the opening example of the NCAA championship. When Memphis’s All-

The Role of Evaluation

The comedian Jerry Seinfeld remarks on the common fear of public scrutiny: “According to most studies, people’s number-

The description of the NCAA championship game reveals that the social context includes more than just heightened arousal for us humans—

This work reveals the physiological consequences of being judged, but what is going on mentally? When we perform in front of others, our thoughts tend to drift to what others are thinking even as we are motivated to do well (“I’d better not blow it”) (Baron, 1986; Sanders & Baron, 1975). On cognitive tasks such as performing mental arithmetic, the threat of social evaluation is likely to bring distracting thoughts to mind, such as self-

Other kinds of performance don’t rely on working memory resources. Becoming an expert in a domain such as basketball, piano, or whichever first-

326

So how do you go about preventing what happened to Memphis from happening to you? Perhaps we can find wisdom in the advice of the basketball legend Charles Barkley, who said, “I know I’m never as good or bad as one single performance. I’ve never believed in my critics or my worshippers, and I’ve always been able to leave the game at the arena.” By disengaging his own self-

Performing With Others: Social Loafing

Research on social facilitation reveals how performance is affected when people perform in front of others. But what about performing with other people on a common task? Those who coach teams or manage organizations know that it can be challenging to get group performance to equal or exceed the sum of its parts. Part of the problem is simply coordinating behavior among two or more people (Latané et al., 1979). But another challenge to optimizing group performance is a phenomenon called social loafing. Social loafing is what happens when an individual exerts less effort when performing as a part of a collective or group than when performing as an individual.

Social loafing

A tendency to exert less effort when performing as part of a collective or group than when performing as an individual.

Researchers have developed clever methods to measure social loafing in the laboratory (Latané et al., 1979). In one study, participants were asked to clap or cheer as loudly as they could as a part of an ostensible study of sound generation and perception. People had to be as loud as possible either alone, in pairs, in a group of four, or in a group of six. If the social context doesn’t matter, then you should clap as loudly when you are asked to do so alone as when you are asked to clap along with a group of five others. And you can argue that maybe even clapping in a group would feel less ridiculous, so each person would clap more loudly than if clapping alone. But that’s not what the researchers found. Instead, the sound generated per person was highest when people were clapping and cheering alone and decreased each time the group size was increased. The performance deficit occurred even when people were doing their clapping and shouting in individual soundproof chambers and believed that the sound they generated would be combined with the sounds of other people yelling their heads off in other chambers.

Think ABOUT

The social loafing effect has been found in domains as varied as rope pulling, swimming, cheering, brainstorming, maze solving, and vigilance tasks—

The Role of Accountability

The biggest reason that people slack off in groups is that they feel less accountable for their efforts. When you are solely responsible for a project, you put forth more effort than when you know your individual contribution to a group outcome will not be recognized. When the clapping study was repeated so that participants believed their contribution to the total noise could be traced back to them, the social loafing effect disappeared (Williams et al., 1981).

327

This finding helps to explain why managers and teachers can increase productivity and performance on group projects by establishing incentives for both individual and group efforts. Is this Big Brother approach of external evaluation the only solution to social loafing? Happily, the answer is no. People are less likely to engage in social loafing merely if they have a way to monitor and evaluate their own performance (Harkins & Szymanski, 1988; Szymanski & Harkins, 1987). So raising the idea of evaluation, even if it comes from oneself, can be enough to eliminate the social loafing effect.

The Role of Expected Effort From Others

In addition to feeling less accountable in a group, people also seem to hold back effort because they believe others will do the same. After all, who wants to be the sucker who does all the work for only a piece of the credit? In studies where one’s partner communicates that he or she intends to work hard for the duration of the task, participants don’t socially loaf even if their own efforts are not being evaluated individually (Jackson & Harkins, 1985).

If you find yourself working in a group and are concerned that others might start slacking off, asserting the level of effort that you intend to put forth can encourage your colleagues to make a greater effort.

The Role of Perceived Dispensability

A third reason for social loafing is that people in a group can feel that their own efforts are not that important to the group outcome (Kerr & Bruun, 1983). For example, many people don’t vote in elections because they feel that their one individual vote will not have much impact. However, the type of task can determine these feelings of dispensability. In some kinds of tasks, called disjunctive tasks, the most skilled members of the group determine the outcome. Imagine a team quiz show or a debate team in which one genius can lead to group success. On conjunctive tasks, the group will do only as well as the worst performer. For example, in mountain climbing, the team can get up the mountain only as fast as its slowest member. The research shows that when group tasks are disjunctive, the most skilled members of the group make the greatest effort, whereas the least skilled members slack off. On conjunctive tasks, the least skilled members exert the greatest effort, and the most skilled members slack off.

If you’re leading a group and want maximum effort from everyone, you can capitalize on these effects by making your best performers view the task as disjunctive and your lesser performers perceive it to be conjunctive. In this way, all group members will believe their efforts are indispensable.

When the Value of the Group and Its Goal Are High

The twin Petronas Towers in Malaysia were constructed by workers from two different countries who competed against one another to finish their tower first.

At the heart of the social loafing phenomenon is an assumption that people value what they can do individually more than what they can accomplish as a group. But in the real world, we freely engage in group activities ranging from team sports to community fundraisers. In these contexts, the group itself has value for us and is an extension of our own identity. When groups are cohesive or composed of friends, people are less likely to loaf (Karau & Williams, 1997). Similarly, people who value social relationships a great deal show less social loafing. For example, women and East Asians (groups that both tend to focus on maintaining relationships) are less susceptible to social loafing than more agentic and individualistic groups like American males (Karau & Williams, 1993). Also, social loafing is less likely when people feel that the task is interesting, personally meaningful, or comes with an attractive reward (Brickner et al., 1986; Zaccaro, 1984).

328

Competition between groups probably has the same effect. When construction on the Petronas Towers in Malaysia began in 1993, they were planned to be the tallest structure in the world. Because the plan called for two identical towers to be built simultaneously, each tower was contracted to a different company, Tower One to a Korean corporation and Tower Two to a Japanese firm. Whether by design or happy accident, the pace of building soon became a matter of national pride for the construction workers, who marked their progress by comparing the heights of two flags that steadily rose higher as the build advanced. (The Korean team won the race.) With such a visible way to measure progress toward the group goal, social loafing probably was kept to a minimum. If only all construction projects could be so speedy!

Social Facilitation and Social Loafing Compared

At this point, you might be thinking that social loafing and social facilitation seem to contradict one another. According to social facilitation theory, performing in a social context heightens people’s concern with being evaluated, improving their performance on an easy task and impairing performance on a difficult task. But research on social loafing has found that performing in a social context can reduce people’s concern with being evaluated, leading to worse performance on an easy task and sometimes elevating performance when the task is challenging. What gives? It’s important to remember that the nature of the social context in these two examples is very different. In the context of social facilitation, others stand by watching you perform, and you feel yourself in the spotlight. In the context of social loafing, others are working alongside you toward a common goal, and your own individual efforts feel anonymous.

The nature of the performance tasks studied in these two contexts also might differ in other important ways. In most studies of social loafing, performance is mostly a matter of motivation. It only takes effort to clap or cheer or pull a rope. On easy tasks such as these, being accountable or watched will increase effort and boost performance. On the other hand, performance is impaired under another’s gaze on tasks for which effort doesn’t guarantee success. You cannot ace your college boards merely if you are motivated enough; you still need to have the background knowledge and cognitive skills to reason through and correctly solve complex problems. The threat of being negatively evaluated can reduce performance even when motivation is high (Forbes & Schmader, 2010).

Deindividuation: Getting Caught Up in the Crowd

Sometimes when individuals are in groups or crowds, they lose their sense of individuality. This psychological state is known as deindividuation. Deindividuation is the opposite of heightened self-

Deindividuation

A tendency to lose one’s sense of individuality when in a group or crowd.

People are most likely to feel deindividuated when they are overstimulated by sights and sounds, high in cognitive load, and physiologically aroused, and when there are few if any cues distinguishing them from a surrounding crowd. In this state, people often behave in more extreme ways than they otherwise would. In one study, participants who dressed identically and wore hoods over their heads were more aggressive toward a stranger than participants who could be identified at a glance (Zimbardo, 1970).

Deindividuation may help account for especially egregious actions that people sometimes engage in during wars, riots, lynchings, and incidents in which a crowd panics, leading to people being trampled to death. For example, Robert Watson (1973) found that in cultures in which warriors tend to hide their identities with paint or masks, killing, torture, and mutilating of captives is more common. A review of newspaper accounts of 60 lynchings of African-

329

Although deindividuation likely contributes to many instances of horrifying behavior in crowds, bad behavior is not an inevitable consequence of being in a large group of people. If the salient cues in the situation are to do something positive, then deindividuation can foster prosocial behavior. In one study, female participants were asked to wear the same nurses’ uniform rather than the ominous robes and hoods that participants wear in similar studies. In this case, deindividuation led to less aggression toward a stranger (Johnson & Downing, 1979). Wearing the uniform may have obscured the participants’ individual identities, but it also cued them to treat others with care. In addition, whereas deindividuation can increase cheating and theft when we see others committing crimes, it can also increase donations to charity if that’s what the crowd is doing (Nadler et al., 1982). Deindividuation makes it more likely that people will conform to what others around them are doing, for better or worse.

|

Social context influences performance. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Social facilitation theory (individual performance with an audience) It first was thought that an audience facilitates performance on a task, but further research clarified that having an audience facilitates one’s dominant response to a task. Arousal facilitates the dominant response across species. In humans, feeling challenged can boost performance, but feeling threatened can impair performance. The threat of social evaluation is distracting. On cognitive tasks, it absorbs working memory, leaving fewer resources for the task at hand. On well- |

Social loafing (performing together) The individual exerts less effort when performing as part of a group than as an individual. To avoid social loafing: Monitor and evaluate performance. Declare your own level of effort. Distinguish disjunctive and conjunctive tasks. Make the task more interesting or rewarding. Maintain intragroup cohesion and intergroup competition. |

Deindividuation When people feel anonymous, they are more likely to do what others around them are doing, for better or for worse. |