9.5 Group Decision Making

Earlier we noted that groups are able to accomplish goals that individuals cannot accomplish on their own. These goals include maximizing performance and productivity, but another important goal of groups is to make decisions—

330

In theory, groups have significant advantages over individuals when it comes to decision making. For instance, if four doctors are discussing a difficult medical problem, they can combine their unique knowledge and experience, consider diverse perspectives, and analyze alternative courses of action to determine which is best. Therefore, it seems like an obvious prediction that the doctors would make a better decision together than they would individually. In reality, however, the benefits of group decision making can be subverted by two psychological processes that get in the way of clear thinking: group polarization and groupthink.

Group Polarization

Imagine that, as part of a psychology experiment, you are asked to read hypothetical scenarios describing different people making decisions. One scenario describes a man deciding between taking a new job that pays a lot but may not last (a risky alternative) or keeping his current job (a conservative alternative). After reading each scenario, you are asked which alternative you personally would choose. Next, you are asked to discuss the same scenarios with a group of participants and come to a joint decision about each scenario.

When do you think you would make riskier decisions, when thinking about the scenarios alone or discussing them with others as a group? Common sense would say that, during group discussions, people will put the brakes on each other’s extreme views or rash proposals, and as a result the group will make more conservative decisions. But when Stoner (1961) conducted a study like the one just described, he found the opposite result: Participants made riskier decisions as a group than they did on their own, a tendency that came to be known as risky shift (Cartwright, 1971).

The story gets more interesting, though. Researchers who followed up on these findings found that, for some decisions, groups did in fact take more conservative, middle-

Researchers eventually discovered that when people discuss their opinions with like-

Group polarization

A tendency for group discussion to shift group members toward an extreme position.

This discovery reveals that group discussion amplifies the original leanings of individuals in the group. If each individual member of the group leans toward a risky alternative prior to the group discussion, they shift toward an even riskier position after group discussion. And, conversely, if each individual initially prefers a more conservative alternative, group discussion shifts them toward extreme caution (Lamm et al., 1976).

If group polarization amplifies group members’ initial leanings, then we would expect group discussion to intensify initial attitudes about a variety of topics, not just decisions about risk. Numerous studies show that this is the case: When women who were moderately feminist discussed gender issues with each other, they became strongly feminist (Myers, 1975). French students who initially liked their president and disliked Americans felt stronger in both directions after group discussion (Moscovici & Zavalloni, 1969). High school students who leaned toward little racial prejudice before a group discussion became even less prejudiced after discussing racial issues with like-

Part of what makes group polarization interesting is that it seems to contradict the research on norm formation. If you look back at our discussion of conformity in chapter 7, you’ll recall Sherif’s (1936) finding that when individuals were put together to voice their opinions about something (in that case, the movement of a single point of light), they made middle-

331

Exposure to New Persuasive Arguments

When others add new arguments to support an opinion, the group’s initial attitude becomes more extreme.

The persuasive arguments theory (Burnstein & Vinokur, 1977) explains group polarization through the concept of informational influence, which occurs when you conform to others’ actions or attitudes because you believe they know something that you don’t (see chapter 7). The theory assumes that people begin with at least one good argument to support their initial opinion or attitude (e.g., Mary likes Candidate X because of his immigration policy), but that they probably have not considered all the relevant arguments (e.g., Candidate X’s environmental policy). During group discussion, group members learn new arguments from each other that reinforce the position they already preferred. As a result, the group as a whole adopts a more extreme position.

This process of polarization by persuasive arguments doesn’t even require face-

How do we know that informational social influence is at work here? In one study (Liu & Latané, 1998), participants discussed a topic as a group and then were asked two weeks later how they felt about the topic. Their individual position lined up with their group’s extreme position, not with the less extreme position that they endorsed prior to the discussion. This suggests that learning new arguments from the group changed how these individuals perceived the world, not just what they reported believing.

Trying to Be a “Better” Group Member

If we apply social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954) (see chapter 5), we can explain group polarization as the result of normative social influence, which occurs when you conform to others’ actions or attitudes to be liked (Myers et al., 1980).

When individuals get together to make a decision, they often look around to figure out where the other group members stand on the topic at hand. Once it becomes clear what position the group is leaning toward, a cycle of comparison and amplification is set in motion: One person in the group tries to compare herself favorably with other group members. She wants to be a “better” group member, so she advocates the group’s position but takes it a little further than everyone else. (“You guys seem to like this idea, but I love it!”) Seeing this, another group member tries to present himself to the group even more favorably, so he takes the group’s position even further. (“Oh yeah? I will fight tooth and nail for this idea!!”)

332

The net effect of this cycle is that the group shifts toward a more extreme position. As we would expect from this theory, group discussion is more likely to result in polarized positions when group members are highly motivated to present themselves positively to other group members (Spears et al., 1990).

Groupthink

Groupthink was to blame for the 1986 malfunction and crash of the space shuttle Challenger.

Most of the examples and research findings we’ve used to discuss group decision making deal with informal group contexts and hypothetical decisions. In these contexts, where decisions do not have earth-

Consider this real-

With so much on the line, why would smart people working together make such a bad decision? Irving Janis (1982) tried to answer this question by analyzing notoriously bad foreign policy decisions made by top U.S. officials, including the Bay of Pigs fiasco in 1961 (when President Kennedy and his inner circle launched an ill-

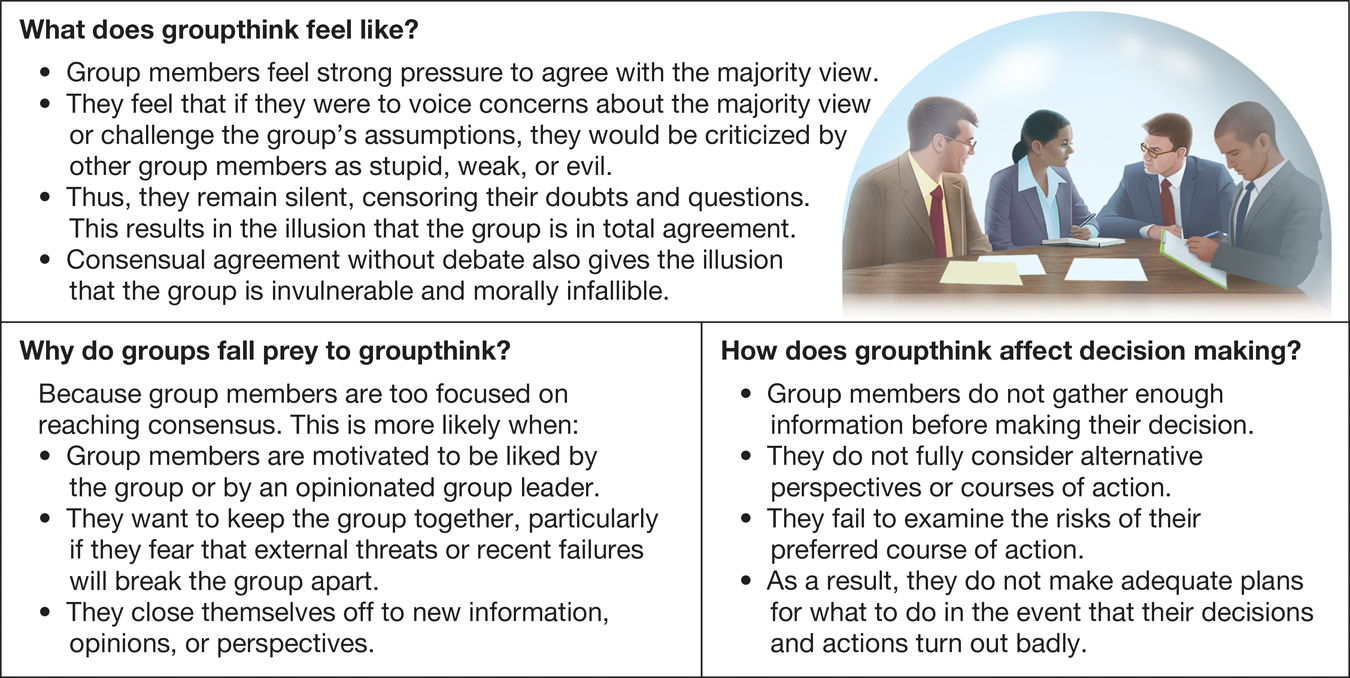

Janis concluded that these bad decisions all suffered from a common problem called groupthink, a kind of faulty group thinking that occurs when group members are so intent on preserving group harmony and cohesion that they fail to analyze a problem completely (FIGURE 9.4). Groupthink is similar to group polarization but taken to the extreme, as if the group has become of one mind, completely unchecked by diverse opinions. Group members start to focus their attention on information that supports their position and ignore information that contradicts it, they stop testing their assumptions against reality, and they stop generating new perspectives on the problem at hand. Eventually they become convinced of the absolute truth and morality of their preferred course of action, and they never stop to think what would happen if they made an error in reasoning.

Groupthink

A tendency toward flawed group decision making when group members are so intent on preserving group harmony that they fail to analyze a problem completely.

FIGURE 9.4

Harmony at All Costs?

Groupthink results in faulty group thinking.

Janis described groupthink using the metaphor of a syndrome that afflicts the group, and he specified several symptoms of groupthink. One hallmark symptom is suppression of dissent: When group members express doubts about the majority’s preferred position, they are harshly criticized and pressured to fall back in line with the majority view. To avoid being reprimanded or excluded, group members begin to censor themselves, meaning that they give the outward impression of agreement even though privately they think that the group is on the wrong track. This results in an illusion of unanimity: It appears that everyone is in agreement, although some group members may harbor serious misgivings. For example, when NASA engineers charged with understanding the safety parameters of equipment pointed out one of the shuttle’s mechanical flaws, they were harshly rebuked and pressured to stay silent by those overseeing the launch (Esser & Lindoerfer, 1989; Vaughan, 1996).

333

Groupthink is especially likely to occur when group members view group cohesion as more important than anything else. In contrast, if group members are less concerned with reaching a consensus or being disliked by other group members, they are more likely to appraise alternative courses of action realistically and express their doubts about the majority view. Janis identified other conditions that make groupthink more likely to occur. One is the isolation of the group from outside sources of information and dissenting voices. Another is the presence of a strong leader who makes his or her opinions and preferences known to the group at the beginning of the discussion. Knowing the leader’s views, the other members want to reinforce those views to win the leader’s approval.

APPLICATION: Improving Group Decision Making

|

APPLICATION: |

| Improving Group Decision Making |

Our discussion of group polarization and groupthink seems to suggest that making decisions as a group is often a bad idea. And sometimes it is. Yet in many cases groups do solve problems and make decisions more effectively than isolated individuals can. This is especially true when groups work together on tasks that require the contribution of different knowledge. For example, groups perform better than individuals on SAT-

Still, the unfortunate reality is that group polarization and groupthink often force groups into an isolated universe where existing beliefs are reinforced and the status quo is justified. Fortunately, groups can use strategies to avoid these pitfalls.

Increase Group Diversity

Recall that group polarization happens when all the group members—

Diverse groups can make better decisions than homogeneous groups because they bring together unique viewpoints and past experiences that provide a broader framework for a problem.

334

If the group cannot find someone who genuinely disagrees with the majority view, they can designate a group member to play “devil’s advocate,” someone who is given free license to search actively for flaws in the reasoning and plans proposed by the other members of the group. This will help the group to consider the relevant information more carefully before deciding on a course of action (Nemeth, Brown et al., 2001; Nemeth, Connell et al., 2001).

Group diversity is also a powerful safeguard against groupthink. Although we may feel more comfortable discussing decisions in groups of like-

Reinterpret Group Cohesiveness

Overemphasizing the importance of group cohesion can create a breeding ground for group polarization and groupthink. That doesn’t necessarily mean, however, that improving group decision making requires squelching group cohesiveness. Rather, group members can reinterpret what it means to be a cohesive group.

Usually people interpret cohesiveness as a norm to maintain the group’s unity and harmony, and to make sure that all group members get along. But groups also can be cohesive in their commitment to help group members make the best possible decisions. That is, rather than thinking of cohesiveness as pushing the group toward consensus, think about it as a promise to reach the best possible outcome and prevent the group from doing something harmful.

Studies show, in fact, that if group members think about how one of the group’s norms could harm the group, the ones who are strongly identified with the group voice their dissent about that norm, whereas those who are weakly identified stay silent (Packer, 2009). Although we might expect that highly identified group members would be reluctant to say anything that challenges the group’s majority views, in actuality they care so much about the group that they are the first to voice their dissent to protect the group from a bad decision. Groups make better decisions when they follow a norm of sharing constructive criticism than when they focus on maintaining group harmony (Postmes et al., 2001).

Encourage Individuality

Recall that according to the social comparison theory of group polarization, groups shift toward more extreme positions because group members are concerned with other group members liking them. Thus, they exaggerate their agreement with the group’s position. This suggests that group polarization would be reduced if group members focused on themselves as individuals and cared less about how they are evaluated by the group. Indeed, one study showed that group discussion did not polarize group members’ initial attitudes if, prior to the discussion, group members were primed to focus on their unique individual qualities (Lee, 2007).

335

Think ABOUT

The same holds true for groupthink, which occurs in large part because group members fail to break from the group norm and voice their doubts about ideas they perceive as wrong or harmful. If group members are led to believe that they are personally responsible for the outcome of their group’s decision, they are less likely to fall victim to groupthink tendencies (Kroon et al., 1991). Consider this research on groupthink and individuality side-

|

Group Decision Making |

|

In theory, groups have more resources than do individuals for making decisions, but two psychological processes, group polarization and groupthink, can subvert good group decision making. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Group polarization Group members’ initial leanings are intensified in a cycle of amplification and comparison with like- |

Groupthink Group members intent on preserving group harmony fail to analyze a problem completely. |

Groups can avoid problems of group decision making by: Encouraging group diversity and ensuring the presence of dissenting voices. Focusing on achieving the best outcome rather than group harmony. Encouraging members to take individual responsibility. |