9.6 Leadership, Power, and Group Hierarchy

Most groups have leaders, individuals with extra power, status, and responsibility. Cultures have presidents, chiefs, or sovereigns. Armies have generals. Sports teams have captains. Committees have chairpersons or heads. A group leader wields power, and where there is a leader, there’s a hierarchical structure.

What Makes a Leader Effective?

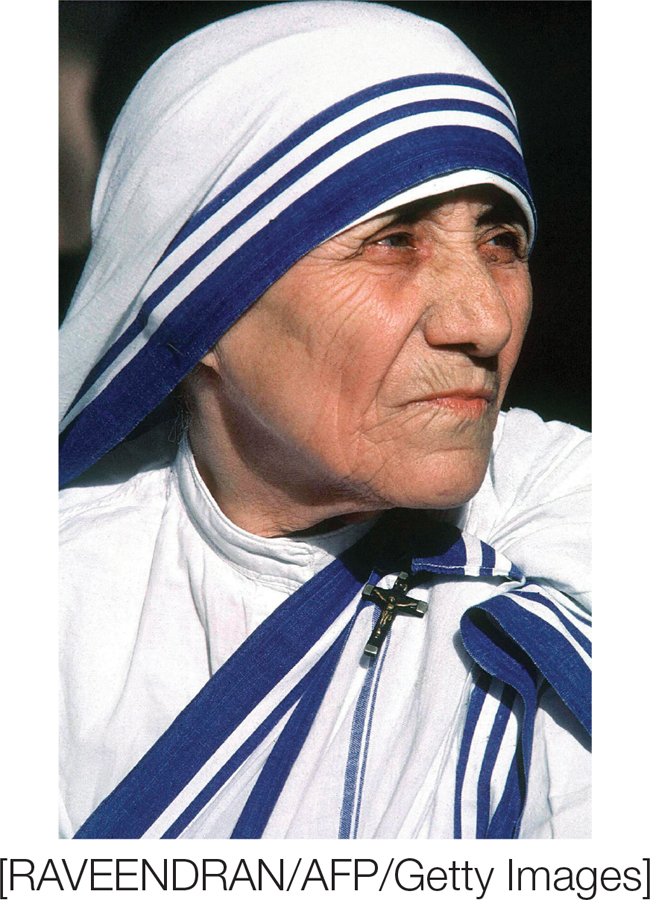

Mother Teresa’s transformational leadership style inspired her followers to commit to humanitarian action.

Conventional wisdom holds that effective leaders are those who possess certain personality traits; thus, they are effective regardless of what kind of situation they and their followers are in. There is some limited evidence that effective leaders tend to be high in the traits of extraversion, openness to experience, and conscientiousness (Judge et al., 2002), and they are more confident in their own leadership abilities (Chemers et al., 2000). However, these correlations are small, meaning that knowing a person’s personality traits tells you surprisingly little about whether that person is or will become an effective leader. Indeed, Simonton (1987) analyzed 100 attributes of past U.S. presidents, including dozens of personality variables, and found no correlation between personality traits and historians’ assessments of their leadership effectiveness. We need a more sophisticated picture of how leaders interact with their followers and the broader social situation.

According to one perspective, effective leaders are transformational (Bass, 1985). The three characteristics of transformational leaders are:

They focus on their followers’ desires and abilities.

They are willing to challenge their followers’ assumptions and behaviors.

They offer an inspirational visionary style.

336

There are many examples of transformational leaders; you can probably think of a bunch on your own. Two prototypes are Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Mother Teresa. You are likely familiar with the enduring effect of Dr. King’s vision. Mother Teresa’s vision transformed her order of nuns from a traditional group focused on prayer and contemplation to an action-

However, very few leaders can achieve this high level of influence. What characteristics allow the average leader to be effective? The answer depends on the specific needs of the group members and the goals of the group. We can identify three types of leaders and the needs they satisfy (Fiedler, 1967). Charismatic leaders (see chapter 7) emphasize bold actions and inspire belief in the greatness of the group. Task-

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

Milk: Charismatic Leadership Style

Milk: Charismatic Leadership Style

Milk (Jinks et al., 2008) is a moving biopic about Harvey Milk, an influential figure in the movement for gay civil rights. In depicting Milk’s rise to leadership, the movie illustrates a number of features of an effective leadership style. The story begins in the Castro district of San Francisco in the early 1970s. Milk, played by Sean Penn, has just moved from New York, and although he is enamored of his neighborhood’s charm, he is outraged by everyday acts of discrimination against gays in his new city. Police harassment and murderous gay-

Fed up, Milk stands on top of a wooden crate and announces to his neighbors that it’s time to fight back. So begins his rise into the political spotlight from a grassroots activist—

To answer this question, let’s unpack the concept of charisma, introduced as one of the qualities of an effective leader. Charisma is that special magnetism that we’ve all seen in larger-

Early in his career, Milk was a relationship-

First, he tells people that the gay rights movement is big, a social movement on a grand scale with far-

Guided by the charismatic leadership of Harvey Milk (portrayed by Sean Penn in the movie Milk), gay rights supporters felt united in a grand mission to overcome discrimination.

Second, he tells people that, by supporting the gay rights movement, they have an opportunity to be part of a lasting legacy that will make a mark on history. For example, he says to members of his campaign, “If there should be an assassination, I would hope that five, ten, one hundred, a thousand would rise. I would like to see every gay lawyer, every gay architect come out—

A third message in Milk’s heroic vision is that there is a clear enemy out there who is holding society back from progress. In 1978, Anita Bryant, a former singer and model, started advocating for a proposition that would ban gays from teaching in schools. Armed with moral rhetoric and the support of the Christian community, she got this legislation passed in Florida and was gaining traction in other states. Milk initially feels defeated by Anita Bryant’s success, but when he walks into the street, he finds that it is exactly what was needed to bring the gay community’s anger to the boiling point. Now hundreds of citizens are ready to take action. Milk seizes the moment, grabs a bullhorn, and says, “I know you’re angry. I’m angry. Let’s march the streets of San Francisco and share our anger.”

He leads the march to the steps of City Hall, where he gives the people the enemy they want: “I am here tonight to say that we will no longer sit quietly in the closet. We must fight. And not only in the Castro, not only in San Francisco, but everywhere the Anitas go. Anita Bryant cannot win tonight. Anita Bryant brought us together! She is going to create a national gay force!”

Because of Milk’s charismatic leadership style, he is remembered today as a major figure in the continuing struggle for equal human rights.

337

None of these leadership types is more effective than the others in every context; rather, leadership effectiveness depends on a match between leadership type and the situation. Let’s illustrate by looking at leaders in the context of the workplace. In some work situations, group members have clearly defined tasks and are relatively free from conflict. In these highly structured situations, people happily work toward common goals, and so a leader has less need to attend to their feelings or interpersonal dynamics. Task-

In other work situations, group members are confused about what they should be doing and often have a difficult time working together. Relationship-

338

Power Changes People

History is replete with scandals involving powerful people who abuse their advantages and turn a blind eye toward the suffering of others. In an oft-

Loosened Inhibitions

Just as people with power have greater access to and control over resources, they also seem to have greater freedom to do as they please. In contrast, those with little power and low socioeconomic status face many constraints on what they can do and be. Dacher Keltner and colleagues (Keltner et al., 2003) argue that this creates a psychology of behavioral approach for those in greater power positions but a psychology of behavioral inhibition for those in lesser power positions. As we’ve emphasized throughout this textbook, approach and avoidance (or, to use the term employed by these researchers, inhibition) are general motivational orientations toward either achieving positive outcomes and reward (approach) or avoiding negative outcomes and punishments (inhibition).

According to this approach/inhibition theory of power, having an approach orientation means that you engage in goal-

For example, in one study, four members of a fraternity were brought into the lab and encouraged to tease each other (Keltner et al., 1998). In each group, two individuals were relatively new to the fraternity and thus had lower status, whereas two were higher-

339

Less Empathy

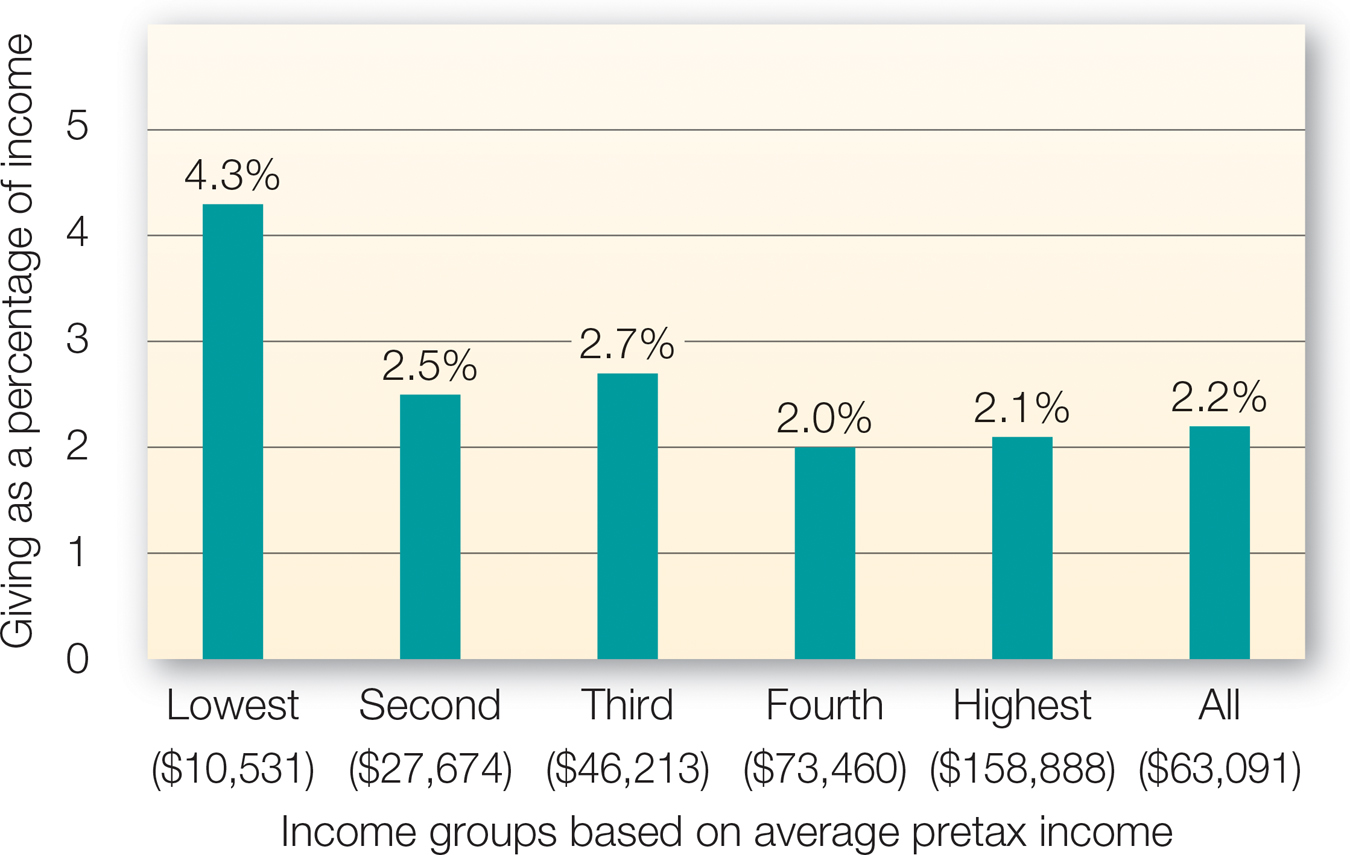

FIGURE 9.5

Those With Less Give More

Those who are less affluent donate a higher percentage of their income to charity.

[Data source: http://www.clearlycultural.com/geert-

We can look at this last finding in terms of subordinates having to monitor what they say around leaders, but it also raises the possibility that those in positions of power are less compassionate toward their subordinates or those who are disadvantaged. More direct evidence for this comes from studies showing that people from higher socioeconomic backgrounds (high SES) might be less generous and charitable than people from lower social classes (Piff et al., 2010). In one study, people who were simply reminded of how they are financially better off recommended that people give about 3 percent of their income to charity, whereas those led to think about their disadvantage in society recommended giving away almost 5 percent of one’s income. This finding seems counterintuitive, because we would expect the people with more financial resources to be in a better position to give more to others. However, having lower status can make people more generous because it cues a sense of compassion and egalitarian values. Other data on charitable giving seem to support these trends (see FIGURE 9.5).

Related findings show that people in power positions tend to be insensitive toward less powerful others. For instance, powerful people seem to have difficulty exhibiting a concrete emotional connection to other people’s suffering, sometimes even seeing them as less human (Gwinn et al., 2013; van Kleef et al., 2008). In addition, people in power are more likely to use stereotypes to form impressions of lower status individuals (Goodwin et al., 2000), devalue or take credit for the contributions of their underlings (Kipnis, 1972), and bring to mind implicit prejudices toward outgroups (Guinote et al., 2010). But those in power will be mindful of their subordinates’ individuating characteristics when doing so is relevant to what they are trying to accomplish (Overbeck & Park, 2001).

Together, this research suggests that the benefits of having power can come at the cost of being less able to empathize with or be charitable to those without power.

Hierarchy in Social Groups

The fact that most groups have leaders also means that groups are often organized hierarchically, with some members having higher status than others. Although some group members have subordinate roles, they are nevertheless critical for helping the group function as a whole. For example, a beehive is a complex social structure operating in the service of one queen bee, who lays eggs. Although she might seem to have high status in this social hierarchy, the entire system would fail without swarms of female worker bees. Though sterile, the worker bees have the responsibilities of collecting honey, building the nest and caring for the larvae. The sole purpose of the male drones is to mate with a new queen once and then die. (How’s that for a one-

340

It’s notable that the bee hierarchy is highly inflexible, with each bee having a fixed role and status. Primate societies are more flexible, but even in chimpanzee colonies, behavioral roles are largely based on biological characteristics such as age, sex, and physical strength. In human societies, although such characteristics are still influential, roles are also far more likely to be based on other socially constructed characteristics.

According to social dominance theory (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999), when human societies grow large enough to produce a surplus of food and other basic resources, the division of labor expands beyond fixed roles stemming from biological characteristics to the creation of arbitrary sets, groups of people distinguished by culturally defined roles, attributes, or characteristics. In addition to those who cultivate food, care for children, and offer physical security, our society includes people who specialize in providing spiritual guidance, entertaining us with music and stories, hauling away our trash, or even teaching us about the complexities of our own society. Depending on the cultural values of a society, some of these groups of people are afforded higher status, and their activities are deemed more valuable than those of groups afforded lower status. Social dominance theory proposes that to maintain stable relationships between these different groups, people generally endorse beliefs that legitimize an existing social hierarchy.

Social dominance theory

The theory that large societies create hierarchies, and that people have a general tendency to endorse beliefs that legitimatize that hierarchy.

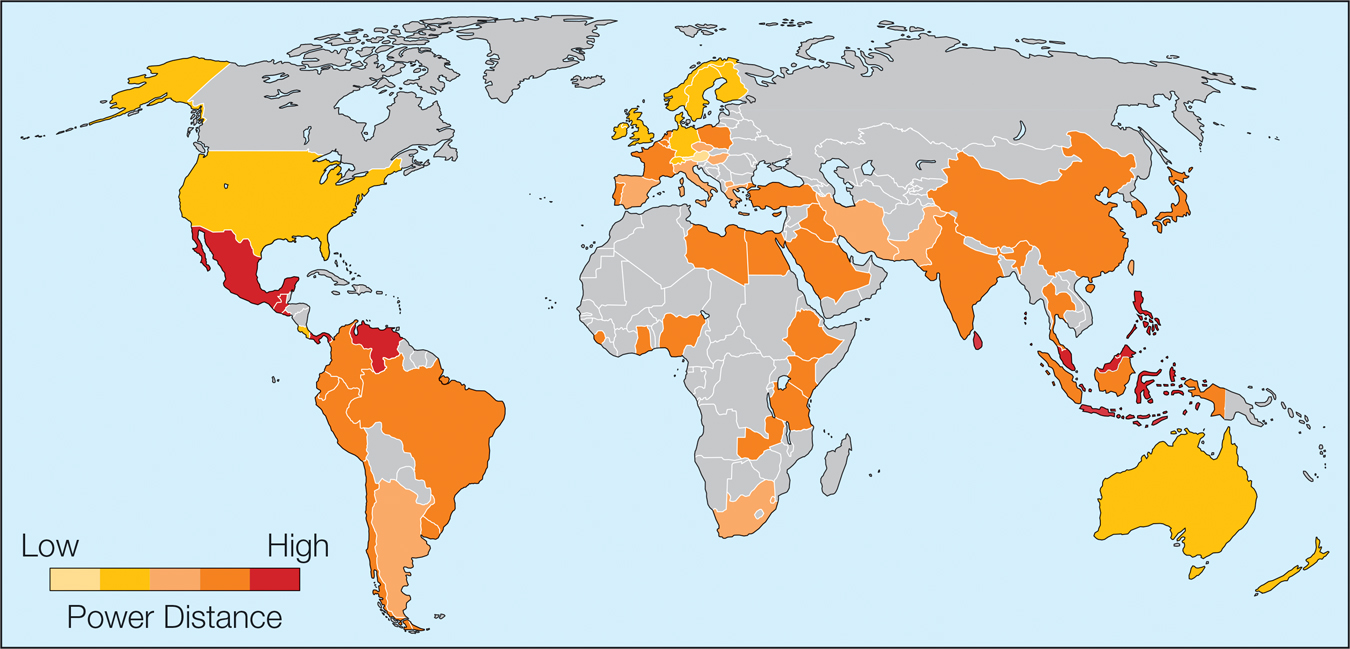

FIGURE 9.6

Power Distance Around the World

Countries shaded in darker colors have a higher power distance, valuing hierarchy and respect for authority. (No data were available for countries shown in gray.)

[Research from: Hofstede et al. (2010) This material is the creation and intellectual property of Kwintessential Ltd (www.kwintessential.co.uk)]

Of course, we see cross-

Power distance

Variation in the extent to which members of a culture or organization (especially those with less power) accept an unequal distribution of power.

341

Legitimizing Hierarchy

A central idea we have touched on throughout this textbook is that much of our social reality is based on a cultural worldview that is constructed and maintained by the consensus of those who live within that reality. This means that for advantaged groups to stay in power and for group hierarchies to persist, individuals across society need to believe in the legitimacy of their leaders, the institutions that maintain them, and the social system in general. Thus, individuals generally believe that group-

Social dominance orientation is linked to many aspects of a person’s lifestyle, including the career path he or she chooses. Compared with an average cross-

In chapter 2, we discussed the importance of a cultural worldview in providing structure and meaning for people’s day-

A rather ironic consequence of believing in legitimizing myths is that the people who are advantaged in society may be more likely than underprivileged groups to claim that they are unfairly discriminated against. For example, although both Whites and Latinos can have relatively high levels of social dominance orientation, only for Whites (the more advantaged group in American society) do these beliefs predict increased perceptions that they are victims of ethnic prejudice (Thomsen et al., 2010). Consider the following experiment, in which college students were asked to role play a situation in which they were applying for a managerial position (Major et al., 2002). White participants who learned that they had been passed over for the job by a Latino manager who favored a Latino applicant were more likely to claim that they were discriminated against than were Latino participants who were passed over by a White manager who favored a White applicant. In both of these studies, we see members of the advantaged group, especially those who believe in the legitimacy of their advantaged position, crying foul when their advantaged position seems to be called into question.

342

Legitimizing myths and social roles provide a framework that reinforces the rigidity and stability of the existing social hierarchy. According to system justification theory (Jost & Banaji, 1994), negative stereotypes get attached to groups partly because they help to explain and justify why some individuals are more advantaged than others. For example, if as a culture we label the homeless as being dim-

System justification theory

The theory that negative stereotypes get attached to groups partly because they help to explain and justify why some individuals are more advantaged than others.

Although it’s easy to understand why members of advantaged groups would want to maintain their legitimizing beliefs, the more remarkable phenomenon is that members of objectively disadvantaged groups in society often do, too. As we noted in our discussion of social identity theory earlier in this chapter, it’s quite common for individuals to show ingroup bias, a preference for their own group over outgroups. This bias is often greater in advantaged groups than in disadvantaged groups. Conversely, some members of disadvantaged groups actually show a preference for the higher-

As noted in the earlier description of the concept of power distance, group hierarchies can be preserved only with some amount of buy-

Complementary stereotypes

Both positive and negative stereotypes that are ascribed to a group as a way of justifying the status quo.

This might also mean that it’s not so bad to be part of the working classes, living from paycheck to paycheck, if you believe that the upper classes are snobbish, cold, dishonest, and depressed. In a similar way, although most women reject stereotypes that suggest that women are less competent or intelligent than men, a large percentage still endorse the idea that women are more moral or warm (Glick & Fiske, 1996). In this way, members of disadvantaged groups who endorse positive stereotypes for their groups (e.g., when a woman proclaims that women are more caring then men) inadvertently may be promoting the very system that keeps them in their disadvantaged place.

To acknowledge instead a sense of disadvantage requires a comparison with others who are more advantaged. Karl Marx famously wrote:

A house may be large or small; as long as the neighboring houses are likewise small, it satisfies all social requirement for a residence. But let there arise next to the little house a palace, and the little house shrinks to a hut…. [T]he occupant of the relatively little house will always find himself more uncomfortable, more dissatisfied, more cramped within his four walls” (Marx, 1847).

People are more likely to realize that they are disadvantaged when they can compare themselves with those who are better off.

As Marx’s quote suggests, we tend to compare ourselves with similar others or with those who are close by. Because societies tend to segregate themselves socially and physically on the basis of class membership or other similarities, we most often compare ourselves with people like us—

343

A classic study demonstrated this phenomenon, known as relative deprivation. When they surveyed soldiers in the U.S. Army, Stouffer and colleagues (Stouffer et al., 1949) found interesting discrepancies between the men’s reported satisfaction with aspects of their jobs and the actual facts about their jobs. For example, a job in the air corps led to twice as many opportunities for promotion than did a job in the military police. But men in the military police reported much higher satisfaction with their access to promotion opportunities than did men in the air corps. Why? Because men in the air corps were more likely to come into contact with their promoted peers and feel unhappy about their own subordinate status. With fewer promoted peers in the military police, M.P.s proved that ignorance can sometimes be bliss.

Relative deprivation theory

A theory stating that disadvantaged groups are less aware of and bothered by their lower status because of a tendency to compare their outcomes only with others who are similarly deprived.

Predicting Social Change

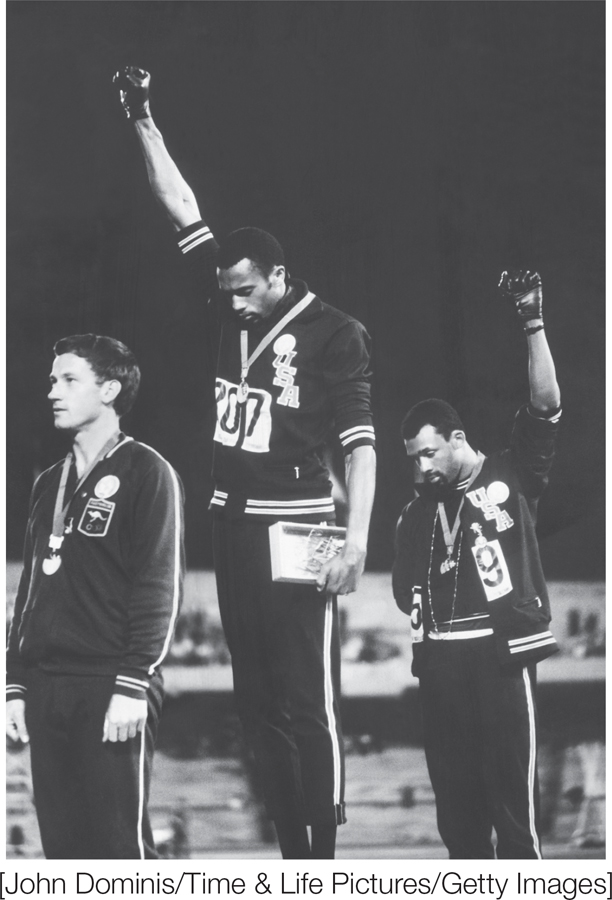

The black power movement of the 1960s was promoted by prominent and successful African Americans, such as Tommie Smith and John Carlos, medalists at the 1968 Summer Olympics.

Clearly social upheaval does sometimes happen, and people in disadvantaged groups often do become disillusioned with a system that makes life difficult for them, their friends, and their families. To predict when these social changes will occur, researchers have drawn on social identity theory. This theory highlights several factors that can determine whether members of lower status groups choose to work within the system toward their own individual goals (try to increase individual mobility) or resist and try to change the status quo in the service of group goals (engage in collective action). In a nutshell, those who fight for the cause of their disadvantaged group often believe that (1) the boundaries between groups are impermeable; (2) the current structure is illegitimate but also unstable; and thus (3) it can be changed.

Individual mobility

A strategy whereby individuals work within the system to achieve their own goals rather than those of the group.

Collective action

Efforts by groups to resist and change the status quo in the service of group goals.

Together, these three perceptions increase identification with and loyalty to the ingroup, which promotes actions to elevate the status of that group (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Research has supported these ideas with both experimental studies that create groups in the lab (Ellemers et al, 1988) and survey research with real-

344

The permeability of group boundaries, sometimes studied as the belief in a meritocracy or the belief that one can advance one’s lot in life through hard work, is particularly interesting as a predictor of collective action. During the 1960s in America, the fight for civil rights was spearheaded by the black power movement. Most of the members of this movement, however, were not the poorest and most disadvantaged Blacks but rather were members of the emerging Black middle and upper class (Caplan, 1970). Although individual mobility efforts can allow people to rise within their group, sometimes a move to collective action does not happen until relatively advantaged members of a lower-

|

Leadership, Power, and Group Hierarchy |

|

Most groups have leaders who wield power and are at the top of a hierarchy. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Leadership style Some leaders are transformational, but in general, effective leaders match their approach to the demands of the situation. Leaders can be charismatic, task oriented, or relationship oriented. |

Effects of power Power leads people to be more approach oriented and less inhibited. People in power tend to have less empathy and can be less generous to those in need. |

Hierarchies As societies grow, work shifts from basic divisions of labor to culturally defined roles. Power- People tend to regard existing hierarchies as legitimate, even when they are disadvantaged by them. Social change occurs when successful members of disadvantaged groups encounter barriers and act collectively to change the status quo. |