The Treatment of Mental Disorders

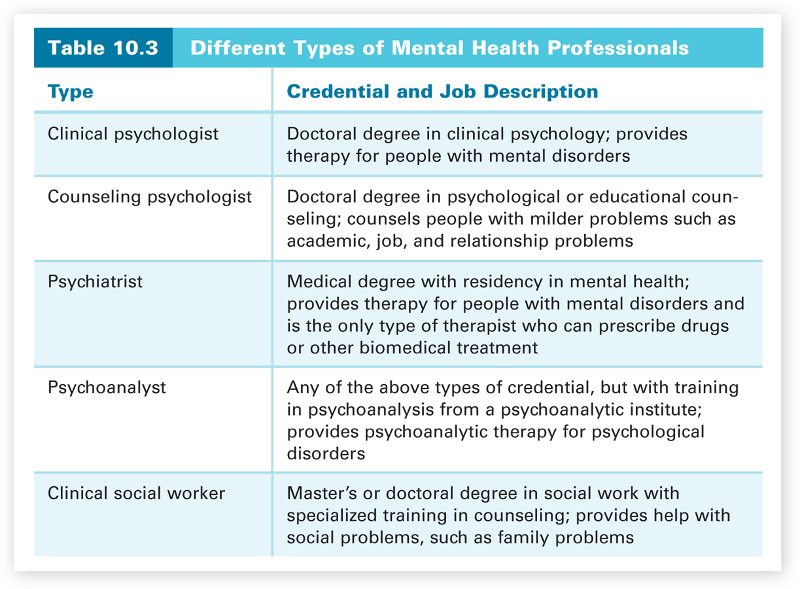

Before discussing treatment for disorders (types of therapy), we need to describe the various types of mental health professionals who treat disorders. Table 10.3 lists most of the major types of mental health professionals, along with the type of credential and the typical kinds of problems they treat. States have licensing requirements for these various mental health professionals, and it is important to verify that a therapist is licensed. There is also one major difference between psychiatrists and the other health professionals. Psychiatrists are medical doctors. This means that psychiatrists can write prescriptions for medical treatment of patients. This is especially important because drug therapy is the major type of treatment for many disorders. To circumvent this prescription-writing problem, nonpsychiatrist mental health professionals typically work in a collaborative practice with medical doctors.

There are two major types of therapy: biomedical and psychological. Biomedical therapy involves the use of biological interventions, such as drugs, to treat disorders. Psychotherapy involves the use of psychological interventions to treat disorders. Psychotherapy is what we normally think of as therapy. There is a dialogue and interaction between the person and the therapist. They talk to each other. This is why psychotherapies are sometimes referred to as “talk therapies.” The nature of the “talk” varies with the approach of the therapist. The behavioral, cognitive, psychoanalytic, and humanistic approaches all lead to different styles of psychotherapy. In biomedical therapy, however, a drug or some other type of biological intervention is used to treat disorders. The interaction is biological, not interpersonal. As with psychotherapies, there are different types of biomedical therapy—drug therapy, electroconvulsive therapy, and psychosurgery. We must remember though that this either-or distinction between biomedical therapy and psychotherapy is somewhat obscured by the fact that psychotherapy does lead to changes that take place in the brain. So the end result (changes in the brain) is the same for both types of therapy, but the means for achieving this result are different. We will first consider biomedical therapies and then the major types of psychotherapy.

Biomedical Therapies

Biomedical therapies for disorders have a long history, reaching back hundreds of years. Looking back, these earlier treatments may seem inhumane and cruel, but remember that we are assessing these treatments given our current state of medical and psychological knowledge, which is far superior to that available when such treatments were used. Let’s consider a couple of examples.

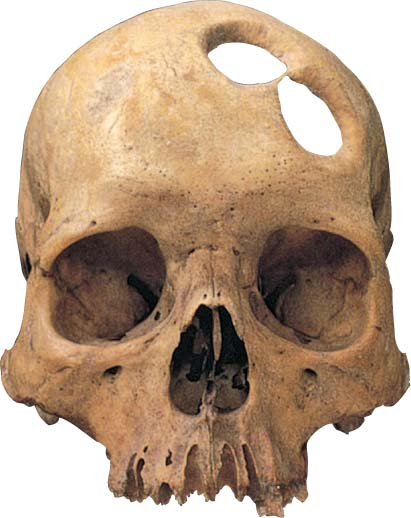

Possibly the earliest biological treatment was trephining, which was done in the Middle Ages. In this primitive treatment, a trephine (stone tool) was used to cut away a section of the person’s skull, supposedly to let evil spirits exit the body, thus freeing the person from the disorder. A treatment device from the early 1800s was called the “tranquilizing chair.” This device was designed by Benjamin Rush, the “father of American psychiatry,” who actually instituted many humane reforms in the treatment of mental patients (Gamwell & Tomes, 1995). The treatment called for patients to be strapped into a tranquilizing chair, with the head enclosed inside a box, for long periods of time. The restriction of activity and stimulation was supposed to have a calming effect by restricting the flow of blood to the patient’s brain. Such “therapies” seem absurd to us today, as does the fact that well into the nineteenth century, many mental patients were still being kept in chains in asylums, untreated. The history of therapy is a rather sad one.

Even the more contemporary biomedical treatments exist in an atmosphere of controversy. Most people have strong, negative feelings about shock therapy, and the most frequently used biomedical treatment, drug therapy, is shrouded in conflict (Barber, 2008; Moncrieff, 2009; Valenstein, 1988). Why? Biomedical treatments are very different from undergoing psychotherapy. Direct biological interventions have a more powerful downside, because they involve possibly serious medical side effects. For example, high levels of some drugs in the blood are toxic and may even be fatal. Careful monitoring is essential. As we discuss the major types of biomedical treatments, we will include discussion of some of these potential problems. We start with drug therapy.

Drug therapy. The drugs used to treat mental disorders are referred to as psychotropic drugs, and they are among the very best sellers for drug companies, with about 300 million prescriptions written for them yearly in the United States (Frances, 2013). Leading the way are antipsychotic drugs with sales of $18 billion a year and antidepressant drugs with sales of $12 billion a year. Surprisingly, primary care providers, not psychiatrists, write the majority of these prescriptions (Du Bosar, 2009). In addition to antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs, other major psychotropic medications used in drug therapy are antianxiety drugs and lithium. We will discuss all of these, beginning with lithium.

Lithium is not a drug, but rather a naturally occurring metallic element (a mineral salt) that is used to treat bipolar disorder. Lithium was actually sold as a substitute for table salt in the 1940s, but was taken off the market when reports of its toxicity and possible role in some deaths began to circulate (Valenstein, 1988). The discovery of lithium’s effectiveness in combating bipolar disorder was accidental (Julien, 2011). Around 1950, John Cade, an Australian psychiatrist, injected guinea pigs with uric acid, which he thought was the cause of manic behavior, and mixed lithium with it so that the acid was more easily liquefied. Instead of becoming manic, the guinea pigs became lethargic. Later tests in humans showed that lithium stabilized the mood of patients with bipolar disorder. It is not understood exactly how lithium works (Lambert & Kinsley, 2005; Paulus, 2007), but within a rather short period of time, one to two weeks, it stabilizes mood in the majority of patients. Lithium levels in the blood must be monitored carefully, however, because of possible toxic effects—nausea, seizures, and even death (Moncrieff, 1997). Because of these possibly toxic side effects, anticonvulsants (drugs used to control epileptic seizures) are now sometimes prescribed instead for people with bipolar disorder. Anticonvulsants seem to reduce bipolar disorder symptoms but have less dangerous potential side effects.

Antidepressant drugs are drugs used to treat depressive disorders. There are many different types. The first antidepressants developed were monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors and tricyclics (this name refers to the three-ring molecular structure of these drugs). MAO inhibitors increase the availability of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine (which affect our mood) by preventing their breakdown (Julien, 2011). Tricyclics make the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and serotonin more available by blocking their reuptake during synaptic gap activity (Julien, 2011). Like lithium, the effects of both types of antidepressants were discovered accidentally when they were being tested for their impact on other problems (Comer, 2014). An MAO inhibitor was being tested as a possible treatment for tuberculosis when it was found to make the patients happier. In the case of tricyclics, their impact on depression was discovered when they were being tested as possible drugs for schizophrenia.

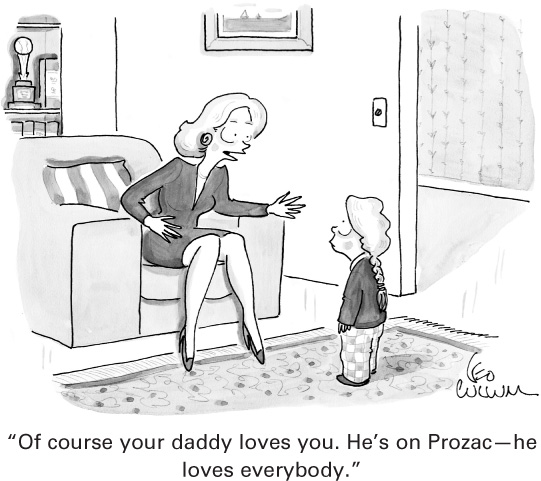

Research indicates that MAO inhibitors are fairly successful in combating depressive symptoms, but they are not used very often because of a potentially very dangerous side effect. Their interaction with several different foods and drinks may result in fatally high blood pressure. Tricyclics are prescribed more often than MAO inhibitors, because they are not subject to this potentially dangerous interaction. The most prescribed antidepressants by far, however, are the more recently developed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Remember from Chapter 2 that their name describes how they achieve their effect—they selectively block the reuptake of serotonin in the synaptic gap, keeping the serotonin active and increasing its availability. The well-known antidepressant drugs Prozac, Zoloft, and Paxil are all SSRIs. The success rate of SSRIs in treatment is about the same as tricylics, but they are prescribed more often because of their milder side effects. Millions of prescriptions have been written for SSRIs, resulting in billions of dollars of sales. Prescriptions for the more recently developed selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs), such as Cymbalta and Effexor, which we discussed in Chapter 2, are also on the increase. None of these various types of antidepressants, however, have immediate effects. It typically takes three to six weeks to see improvement.

A recent survey study of about 12,000 people by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found some interesting results with respect to the use of antidepressants (Pratt, Brody, & Gu, 2011). First, the use of antidepressant drugs has soared nearly 400 percent since 1988, making antidepressants the most frequently used drugs by people ages 18–44. About 1 in 10 Americans aged 12 years and older were taking antidepressants during the period of the study, 2005–2008. As expected, because women are twice as likely to suffer from depression as men, women were more likely to be taking antidepressants than were men, and this was true for every level of depression severity. The survey also found that nearly one in four women ages 40 to 59 were taking antidepressants, more than in any other age-sex group. Of concern, it was found that less than one-third of persons taking an antidepressant and less than one-half of those taking multiple antidepressants had seen a mental health professional in the past year, indicating a lack of follow-up care. This is further complicated by the fact that people who take antidepressants are usually taking them long term. About 60 percent of those taking antidepressants had taken them for 2 years or longer, and 14 percent had taken them for more than a decade.

There is a controversy about the effectiveness of antidepressant drugs, with some researchers arguing that antidepressants are just expensive, overused placebos. Indeed, some recent research indicates that much of their effectiveness can be accounted for by placebo effects—improvements due to the expectation of getting better (Kirsch, 2010; Kirsch et al., 2008). Remember from Chapter 1 that a placebo is an inert substance or treatment that is given to patients who believe that it is a real treatment for their problem. An especially intriguing finding is that placebos that lead to actual physical side effects also lead to larger placebo effects. These placebo effects have sometimes been found to be comparable to the improvement effects of antidepressant drugs (Kirsch, 2010). Some researchers believe that this means much, if not most, of the effect found with antidepressant drugs may be due to placebo effects. However, the difference between drug and placebo effects may vary as a function of symptom severity (Khan, Brodhead, Kolts, & Brown, 2005). A recent meta-analysis of antidepressant drug effects and depression severity found that the magnitude of benefit of antidepressant medication compared to placebo increases with severity of depression symptoms and is significant with very severe depression (Fournier et al., 2010). The benefit may be minimal or nonexistent, on average, in patients with mild or moderate symptoms, but it is significant for patients with very severe depression.

How can we make sense of these placebo effects? One possibility involves neurogenesis, which we discussed in Chapter 2. Remember, neurogenesis, the growth of new neurons, has been observed in the hippocampus in the adult brain (Jacobs, van Praag, & Gage, 2000a, 2000b). The neurogenesis theory of depression assumes that neurogenesis in the hippocampus stops during depression, and when neurogenesis resumes, the depression lifts (Jacobs, 2004). The question, then, is how do we get neurogenesis to resume? There are many possibilities. Research has shown that SSRIs lead to increased neurogenesis in other animals. Both rats and monkeys given Prozac make more neurons than rats and monkeys not given Prozac (Perera et al., 2011). This also seems to be the case for humans taking antidepressants (Boldrini et al., 2009; Malberg & Schechter, 2005). The time frame for neurogenesis also fits the time frame for SSRIs to have an impact on mood. It takes three to six weeks for new cells to mature, the same time it typically takes SSRIs to improve the mood of a patient. This means that, in the case of the SSRIs, the increased serotonin activity may be responsible for getting neurogenesis going again and lifting mood.

Remember, however, what we said about disorders being biopsychosocial phenomena. It is certainly plausible that psychological factors could also have an impact on neurogenesis. Positive thinking, in the form of a strong placebo effect, might also get neurogenesis going again, but possibly not sufficiently enough to deal with very severe depression. A similar claim could be made for the effectiveness of cognitive psychotherapies in which therapists turn the patient’s negative thinking into more positive thinking. The neurogenesis theory is only in its formative stage, but it does provide a coherent framework for the many diverse improvement effects due to drugs, placebos, and psychotherapies.

Antianxiety drugs are drugs that treat anxiety problems and disorders. The best known antianxiety drugs, such as Valium and Xanax, are in a class of drugs called benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines reduce anxiety by increasing the activity of the major inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (Julien, 2011). When GABA’s activity is increased, it reduces anxiety by slowing down and inhibiting neural activity, getting it back to normal levels. Unfortunately, recent evidence has shown that benzodiazepines have potentially dangerous side effects, such as physical dependence or fatal interactions with alcohol; but other types of nonbenzodiazepine antianxiety drugs have been developed with milder side effects. In addition, some antidepressant drugs, especially the SSRIs, have been very successful in treating anxiety disorders.

Antipsychotic drugs are drugs that reduce psychotic symptoms. The first antipsychotic drugs appeared in the 1950s and, as we discussed in Chapter 2, worked antagonistically by globally blocking receptor sites for dopamine, thereby reducing its activity. These drugs greatly reduced the positive symptoms of schizophrenia but had little impact on the negative symptoms. Antipsychotic drugs revolutionized the treatment of schizophrenia and greatly reduced the number of people with schizophrenia in mental institutions. These early drugs, along with those developed through the 1980s, are referred to as “traditional” antipsychotic drugs to distinguish them from the more recently developed “new generation” antipsychotic drugs.

The traditional drugs (for example, Thorazine and Stelazine) produce side effects in motor movement that are similar to the movement problems of Parkinson’s disease. In addition, there is a long-term-use side effect of traditional antipsychotic drugs called tardive dyskinesia in which the patient has uncontrollable facial tics, grimaces, and other involuntary movements of the lips, jaw, and tongue. The new generation antipsychotic drugs (for example, Clozaril and Risperdal) are more selective about where in the brain they reduce dopamine activity; therefore, they do not produce the severe movement side effects such as tardive dyskinesia. They also have the advantage of helping some patients’ negative schizophrenic symptoms. This may be due to the fact that these drugs also decrease the level of serotonin activity.

Regrettably, the new generation antipsychotic drugs have other potentially dangerous side effects and have to be monitored very carefully (Folsom, Fleisher, & Depp, 2006). Such monitoring is expensive; therefore, traditional drugs are often prescribed instead. In addition, the initial optimism for the new generation drugs has been tempered by recent evidence that they do not lead to as much improvement as originally thought (Jones et al., 2006; Lieberman, Stroup, et al., 2005). A recent study of long-term antipsychotic treatment and brain volume also found a negative effect for both traditional and new generation antipsychotic drugs (Ho, Andreasen, Ziebell, Pierson, & Magnotta, 2011). Longer-term antipsychotic treatment was associated with smaller volumes of both brain tissue and gray matter. Other studies have found similar decreases in gray matter in the short term (Dazzan et al., 2005; Lieberman, Tollefson, et al., 2005). Thus, antipsychotic drugs may lead to loss of brain tissue or exacerbate declines in brain volume caused by schizophrenia.

A different type of new generation antipsychotic drug, trade name Abilify, is sometimes referred to as a “third generation” antipsychotic drug because of its neurochemical actions. It achieves its effects by stabilizing the levels of both dopamine and serotonin activity in certain areas of the brain. It blocks receptor sites for these two neurotransmitters when their activity levels are too high and stimulates these receptor sites when their activity levels are too low. Thus, it works in both antagonistic and agonistic ways, depending upon what type of effect is needed. This is why it is also sometimes called a “dopamine-serotonin system stabilizer.” Clinical research thus far indicates that it is as effective as other new generation antipsychotic drugs and may have less severe side effects (DeLeon, Patel, & Crismon, 2004; Rivas-Vasquez, 2003). Given its neurochemical properties, Abilify is also used as treatment for bipolar disorder for those who have not responded to lithium and as an add-on to antidepressant therapy for major depressive disorder (Julien, 2011).

Electroconvulsive therapy. Another type of biomedical therapy is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), a last-resort treatment for the most severe cases of depression. ECT involves electrically inducing a brief brain seizure and is informally referred to as “shock therapy.” ECT was introduced in 1938 in Italy by Ugo Cerletti as a possible treatment for schizophrenia, but it was later discovered to be effective only for depression (Impastato, 1960). The first use of ECT in the United States was in 1940, a couple of years later (Pulver, 1961). How is ECT administered? Electrodes are placed on one or both sides of the head, and a very brief electrical shock is administered, causing a brain seizure that makes the patient convulse for a few minutes. Patients are given anesthetics so that they are not conscious during the procedure, as well as muscle relaxants to minimize the convulsions.

About 80 percent of depressed patients improve with ECT (Glass, 2001), and they show improvement somewhat more rapidly with the use of ECT than with antidepressant drugs (Seligman, 1994). This more rapid effect makes ECT a valuable treatment for suicidal, severely depressed patients, especially those who have not responded to any other type of treatment. Strangely, after more than 50 years we still do not know how ECT works in treating depression. One explanation is that, like antidepressant drugs, the electric shock increases the activity of serotonin and norepinephrine, which improves mood. ECT’s effects also fit the speculative neurogenesis theory of depression. Like SSRIs, electroconvulsive shock increases neurogenesis in rats (Scott, Wojtowicz, & Burnham, 2000). This means that ECT may have an impact on neurogenesis and may do so a little more quickly than antidepressant drugs. Current research seems to indicate that ECT does not lead to any type of detectable brain damage or long-term cognitive impairment, but there is a memory-loss side effect for events just prior to and following the therapy (Calev, Guadino, Squires, Zervas, & Fink, 1995). Regardless of its clear success in treating severe depression, perhaps saving thousands of lives, ECT remains a controversial therapeutic technique because of its perceived barbaric nature. Interestingly, patients who have undergone ECT do not see it in such a negative light, and the vast majority report that they would undergo it again if their depression recurred (Goodman, Krahn, Smith, Rummans, & Pileggi, 1999; Pettinati, Tamburello, Ruetsch, & Kaplan, 1994). Much of the general public’s sordid misconception of ECT likely stems from its inaccurate coverage in the entertainment media (Lilienfeld, Lynn, Ruscio, & Beyerstein, 2010).

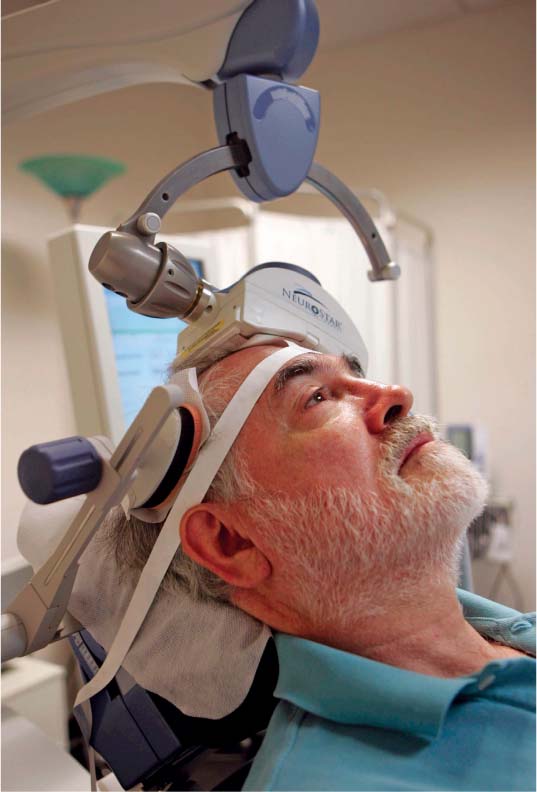

Because of the general public’s negative image of ECT, alternative neurostimulation therapies for the severely depressed are being developed. One promising alternative is transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). In contrast with ECT, which transmits electrical impulses, TMS stimulates the brain with magnetic pulses via an electromagnetic coil placed on the patient’s scalp above the left frontal lobe. This area is stimulated because brain scans of depressed patients show that it is relatively inactive. Typically a patient receives five treatments a week for four to six weeks. Unlike ECT, the patient is awake during TMS, and TMS does not produce any memory loss or other major side effects. Like ECT, it is not exactly clear how TMS works to alleviate depression, but it seems to do so by energizing neuronal activity in a depressed patient’s relatively inactive left frontal lobe. Although some research has shown that it may be as effective as ECT in treating severely depressed patients for whom more traditional treatments have not helped (Grunhaus, Schreiber, Dolberg, Polak, & Dannon, 2003) and its use for this purpose has been approved, more research on this relatively new therapy and its effects is clearly needed.

Psychosurgery. An even more controversial biomedical therapy is psychosurgery, the destruction of specific areas in the brain. The most famous type of psychosurgery is the lobotomy, in which the neuronal connections of the frontal lobes to lower areas in the brain are severed. Egas Moniz, a Portuguese neurosurgeon who coined the term “psychosurgery,” pioneered work on lobotomies for the treatment of schizophrenia (Valenstein, 1986). In fact, he won a Nobel prize in 1949 for his work. No good scientific rationale for why lobotomies should work, or scientific evidence that they did work, was ever put forth, however. Regardless, led by Dr. Walter Freeman, tens of thousands of lobotomies were done in the United States in the 1940s and 1950s (El-Hai, 2005). In 1945, Freeman developed the transorbital lobotomy technique—gaining access to the frontal lobes through the eye socket behind the eyeball with an ice-pick-like instrument, and then swinging the instrument from side to side, cutting the fiber connections to the lower brain (Valenstein, 1986). Freeman didn’t even do the lobotomies in hospital operating rooms. He would travel directly to the mental institutions with his bag and do several in one day. Because it renders the patient unconscious, ECT was often used as the anesthetic. Freeman traveled thousands of miles on psychosurgical road trips to over 20 states and performed nearly 3,500 lobotomies (El-Hai, 2001). The arrival of antipsychotic drugs in the 1950s thankfully replaced the lobotomy as the main treatment for schizophrenia. Unfortunately, these primitive procedures had already left thousands of victims in a zombielike, deteriorated state.

Psychosurgery is still around, but it is very different from the earlier primitive lobotomies (Vertosick, 1997). For example, cingulotomies, in which dime-sized holes are surgically lesioned (burnt) in specific areas of the cingulate gyrus in the frontal lobes, are sometimes performed on patients who are severely depressed or have obsessive-compulsive disorder and who have not responded to other types of treatment. The cingulate gyrus is part of the pathway between the frontal lobes and the limbic system structures that govern emotional reactions. These new procedures bear no resemblance to the earlier lobotomies. They are done in operating rooms, using magnetic resonance imaging to guide the surgery and computer-guided electrodes with minute precision to perform the surgery. Because it involves irreversible brain injury, psychosurgery is done very infrequently today. These procedures are used only in cases of serious disorders when all other treatments have failed, and only with the patient’s permission.

Psychotherapies

In Chapter 8, one type of psychotherapy, psychoanalysis, developed by Sigmund Freud in the early 1900s, was briefly discussed. When thinking about psychoanalysis, we usually think of a patient lying on a couch with the therapist sitting behind the patient and taking notes about the patient’s dreams and free associations. This is actually a fairly accurate description of classical psychoanalysis, but most types of psychotherapy are nothing like this. We’ll discuss psychoanalysis first and then the other three major types of psychotherapy—humanistic, behavioral, and cognitive. Sometimes these four types of psychotherapy are divided according to their emphasis on insight or action. Psychoanalysis and humanistic therapies are usually referred to as insight therapies—they focus on the person achieving insight into (conscious awareness and understanding of) the causes of his behavior and thinking. In contrast, behavioral and cognitive therapies are usually referred to as action therapies—they focus on the actions of the person in changing his behavior or ways of thinking.

Psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis is a style of psychotherapy, originally developed by Sigmund Freud, in which the therapist helps the person gain insight into the unconscious sources of his or her problems. Classical psychoanalysis, as developed by Freud, is very expensive and time consuming. A patient usually needs multiple sessions each week for a year or two to get to the source of her problems. Remember from Chapter 8 that Freud proposed that problems arise from repressed memories, fixations, and unresolved conflicts, mainly from early childhood. Such problems are repressed in the unconscious but continue to influence the person’s behavior and thinking. The task for the psychoanalyst is to discover these underlying unconscious problems and then help the patient to gain insight into them. The difficulty with this is that the patient herself is not even privy to these unconscious problems. This means that the therapist has to identify conscious reflections of the underlying problems and interpret them. The major task of the psychoanalyst, then, is to interpret many sources of input—including free associations, resistances, dreams, and transferences—in order to find the unconscious roots of the person’s problem.

Free association is a technique in which the patient spontaneously describes, without editing, all thoughts, feelings, or images that come to mind. For psychoanalysts, free association is like a verbal projective test. Psychoanalysts assume that free association does not just produce random thoughts but will provide clues to the unconscious conflicts leading to the patient’s problems. This is especially true for resistances during free association. A resistance is a patient’s unwillingness to discuss particular topics. For example, a patient might be free associating and say the word “mother.” A resistance to this topic (his mother) would be indicated by the patient abruptly halting the association process and falling silent. The patient might also miss a therapy appointment to avoid talking about a particular topic (such as his mother) or change the subject to avoid discussion of the topic. The psychoanalyst must detect these resistances and interpret them.

The psychoanalyst also interprets the patient’s dreams, which may provide clues to the underlying problem. According to Freud, psychological defenses are lowered during sleep; therefore, the unconscious conflicts are revealed symbolically in one’s dreams. This means that dreams have two levels of meaning—the manifest content, the literal surface meaning of a dream, and the latent content, the underlying true meaning of a dream. It is the latent content that is important. For example, a king and queen in a dream could really represent the person’s parents, or having a tooth extracted could represent castration. Another tool available to the therapist is the process of transference, which occurs when the patient acts toward the therapist as she did or does toward important figures in her life, such as her parents. For example, if the patient hated her father when she was a child, she might transfer this hate relationship to the therapist. In this way transference is a reenactment of earlier or current conflicts with important figures in the patient’s life. The patient’s conflicted feelings toward these important figures are transferred to the therapist, and the therapist must detect and interpret these transferences.

Classical psychoanalysis requires a lot of time, because the therapist has to use these various indirect clues to build an interpretation of the patient’s problem. It’s similar to a detective trying to solve a case without any solid clues, such as the weapon, fingerprints, or DNA evidence. There’s only vague circumstantial evidence. Using this evidence, the therapist builds an interpretation that helps the patient to gain insight into the problem. This classical style of psychoanalysis has been strongly criticized and has little empirical evidence supporting its efficacy. However, contemporary psychoanalytic therapy, usually referred to as psychodynamic therapy, has proved successful (Shedler, 2010). It is very different than Freud’s psychoanalysis. The patient sits in a chair instead of lying on a couch, sessions are only once or twice a week, and the therapy may finish in months, instead of years. In addition, patients who receive psychodynamic therapy seem to maintain their therapeutic gains and continue to improve after the therapy ends.

Client-centered therapy. The most influential humanistic therapy is Carl Rogers’s client-centered therapy, which is sometimes called person-centered therapy (Raskin & Rogers, 1995; Rogers, 1951). Client-centered therapy is a style of psychotherapy in which the therapist uses unconditional positive regard, genuineness, and empathy to help the person to gain insight into his true self-concept. Rogers and other humanists preferred to use the words “client” or “person” rather than “patient”; they thought that “patient” implied sickness, while “client” and “person” emphasized the importance of the clients’ subjective views of themselves. Remember from Chapter 8 that Rogers assumed that conditions of worth set up by other people in the client’s life have led the troubled person to develop a distorted self-concept, and that a person’s perception of his self is critical to personality development and self-actualization (the fullest realization of one’s potential). The therapeutic goal of client-centered therapy is to get the person on the road to self-actualization. To achieve this goal, the therapist is nondirective; she doesn’t attempt to steer the dialogue in a certain direction. Instead, the client decides the direction of each session. The therapist’s main task is to create the conditions that allow the client to gain insight into his true feelings and self-concept.

These conditions are exactly the same as those for healthy personality growth that were discussed in Chapter 8. The therapist should be accepting, genuine, and empathic. The therapist establishes an environment of acceptance by giving the client unconditional positive regard (accepting the client without any conditions upon his behavior). The therapist demonstrates genuineness by honestly sharing her own thoughts and feelings with the client. To achieve empathic understanding of the client’s feelings, the therapist uses active listening to gain a sense of the client’s feelings, and then uses mirroring to echo these feelings back to the client, so that the client can then get a clearer image of his true feelings. It is this realization of his true feelings that allows the client to get back on the road to personal growth and self-actualization. By creating a supportive environment, this style of therapy is very successful with people who are not suffering from a clinical disorder but who are motivated toward greater personal awareness and growth.

Behavioral therapy. Behavioral therapy is a style of psychotherapy in which the therapist uses the principles of classical and operant conditioning to change the person’s behavior from maladaptive to adaptive. The assumption is that the behavioral symptoms (such as the irrational behavior of the woman with the specific phobia of birds) are the problem. Maladaptive behaviors have been learned, so they have to be unlearned, and more adaptive behaviors need to be learned instead. Behavioral therapies are based on either classical or operant conditioning. We’ll first describe an example of one based on classical conditioning.

Remember the Little Albert classical conditioning study by Watson and Rayner that we mentioned earlier in this chapter when we were discussing phobic disorders. As we pointed out in Chapter 4, Albert’s fear of white rats was never deconditioned, but one of Watson’s former students, Mary Cover Jones, later showed that such a fear could be unlearned and replaced with a more adaptive relaxation response (Jones, 1924). Jones eliminated the fear of rabbits in a 3-year-old boy named Peter by gradually introducing a rabbit while Peter was eating. Peter’s pleasure response while eating was incompatible with a fear response. Over time, Peter learned to be relaxed in the presence of a rabbit. Some consider this to be the first case of behavioral therapy. Jones’s work led to the development of a set of classical conditioning therapies called counterconditioning techniques. In counterconditioning, a maladaptive response is replaced by an incompatible adaptive response. Counterconditioning therapies, such as systematic desensitization, virtual reality therapy, and flooding, have been especially successful in the treatment of anxiety disorders. These three counterconditioning therapies are referred to as exposure therapies because the patient is exposed at some point to the source of his anxiety.

Using Jones’s idea that fear and relaxation are incompatible responses, Joseph Wolpe developed a behavioral therapy called systematic desensitization that is very effective in treating phobias (Wolpe, 1958). Systematic desensitization is a counterconditioning procedure in which a fear response to an object or situation is replaced with a relaxation response in a series of progressively increasing fear-arousing steps. The patient first develops a hierarchy of situations that evoke a fear response, from those that evoke slight fear on up to those that evoke tremendous fear. For example, a person who had a specific phobia of spiders might find that planning a picnic evoked slight fear because of the possibility that a spider might be encountered on the picnic. Seeing a picture of a spider would evoke more fear, seeing a spider on a wall 20 feet away even more. Having actual spiders crawl on her would be near the top of the hierarchy. These are just a few situations that span a possible hierarchy. Hierarchies have far more steps over which the fear increases gradually.

Once the hierarchy is set, the patient is then taught how to use various techniques to relax. Once this relaxation training is over, the therapy begins. The patient starts working through the hierarchy and attempts to relax at each step. First the patient relaxes in imagined situations in the hierarchy and later in the actual situations. With both imagined and actual situations, the anxiety level of the situation is increased slowly. At some of the latter stages in the hierarchy, a model of the same sex and roughly same age may be brought in to demonstrate the behavior before the patient attempts it. For example, the model will touch the picture of a bird in a book before the patient is asked to do so. In brief, systematic desensitization teaches the patient to confront increasingly fear-provoking situations with the relaxation response.

Virtual reality therapy is similar to systematic desensitization, but the patient is exposed to computer simulations of his fears in a progressively anxiety-provoking manner. Wearing a motion-sensitive display helmet that projects a three-dimensional virtual world, the patient experiences seemingly real computer-generated images rather than imagined and actual situations as in systematic desensitization. When the patient achieves relaxation, the simulated scene becomes more fearful until the patient can relax in the simulated presence of the feared object or situation. Virtual reality therapy has been used successfully to treat specific phobias, social anxiety disorder, and some other anxiety disorders (Krijn, Emmelkamp, Olafsson, & Biemond, 2004).

Another counterconditioning exposure therapy, flooding, does not involve such gradual confrontation. In flooding, the patient is immediately exposed to the feared object or situation. For example, in the case of the spider phobia, the person would immediately have to confront live spiders. Flooding is often used instead of systematic desensitization when the fear is so strong that the person is unable to make much progress in systematic desensitization.

Behavioral therapies using operant conditioning principles reinforce desired behaviors and extinguish undesired behaviors. A good example is the token economy that we discussed in Chapter 4. A token economy is an environment in which desired behaviors are reinforced with tokens (secondary reinforcers such as gold stars or stickers) that can be exchanged for rewards such as candy and television privileges. This technique is often used with groups of institutionalized people, such as those in mental health facilities. As such, it has been fairly successful in managing autistic, retarded, and some schizophrenic institutionalized populations. For example, if making one’s bed is the desired behavior, it will be reinforced with tokens that can be exchanged for treats or privileges. A token economy is more of a way to manage the daily behavior of such people than a way to cure them, but we must remember that a behavioral therapist thinks that the maladaptive behavior is the problem.

Cognitive therapy. Behavioral therapies work to change the person’s behavior; cognitive therapies work on the person’s thinking. Cognitive therapy is a style of psychotherapy in which the therapist changes the person’s thinking from maladaptive to adaptive. The assumption is that the person’s thought processes and beliefs are maladaptive and need to change. The cognitive therapist identifies the irrational thoughts and unrealistic beliefs that need to change and then helps the person to execute that change. Two prominent cognitive therapies are Albert Ellis’s rational-emotive therapy (Ellis, 1962, 1993, 1995) and Aaron Beck’s cognitive therapy (Beck, 1976; Beck & Beck, 1995).

In Ellis’s rational-emotive therapy, the therapist directly confronts and challenges the patient’s unrealistic thoughts and beliefs to show that they are irrational. These irrational, unrealistic beliefs usually involve words such as “must,” “always,” and “every.” Let’s consider a simple example. A person might have the unrealistic belief that he must be perfect in everything he does. This is an unrealistic belief. He is doomed to failure, because no one can be perfect at everything they do. Instead of realizing that his belief is irrational, he will blame himself for the failure and become depressed. A rational-emotive therapist will show him the irrationality of his thinking and lead him to change his thinking to be more realistic. This is achieved by Ellis’s ABC model. A refers to the Activating event (failure to be perfect at everything); B is the person’s Belief about the event (“It’s my fault; I’m a failure”); and C is the resulting emotional Consequence (depression). According to Ellis, A does not cause C; B causes C. Through rational-emotive therapy, the person comes to realize that he controls the emotional consequences because he controls the interpretation of the event.

Rational-emotive therapists are usually very direct and confrontational in getting their clients to see the errors of their thinking. Ellis has said that he does not think that a warm relationship between therapist and client is essential to effective therapy. Aaron Beck’s form of cognitive therapy has the same therapeutic goal as Ellis’s rational-emotive therapy, but the therapeutic style is not as confrontational. A therapist using Beck's cognitive therapy works to develop a warm relationship with the person and has a person carefully consider the objective evidence for his beliefs in order to see the errors in his thinking. For example, to help a student who is depressed because he thinks he has blown his chances to get into medical school by not having a perfect grade point average, the therapist would have the student examine the statistics on how few students actually graduate with a perfect average and the grade point averages of students actually accepted to medical school. The therapist is like a good teacher, helping the person to discover the problems with his thinking. Regardless of the style differences, both types of cognitive therapy have been especially effective at treating major depressive disorders.

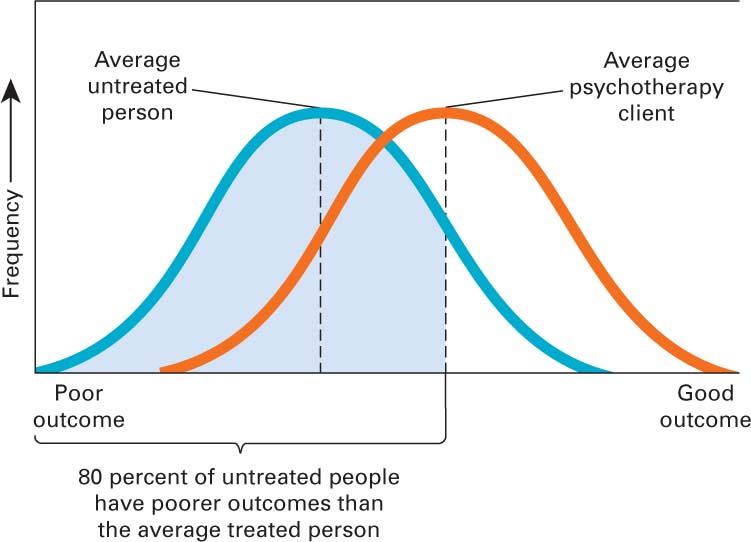

Is psychotherapy effective? Now that you understand the four major approaches to psychotherapy, let’s consider this question: Is psychotherapy effective? To assess the effectiveness of psychotherapy we must consider spontaneous remission. Spontaneous remission is when a person gets better with the passage of time without receiving any therapy. In order to be considered effective, improvement from psychotherapy must be significantly (statistically) greater than that due to spontaneous remission. To answer the question, researchers have used meta-analysis, a statistical technique discussed in Chapter 1 in which the results from many separate experimental studies on the same question are combined into one analysis to determine whether there is an overall effect. The results of a meta-analysis that included the results of 475 studies involving many different types of psychotherapy and thousands of participants revealed that psychotherapy is effective (Figure 10.1). The average psychotherapy client is better off than about 80 percent of people not receiving any therapy (Smith, Glass, & Miller, 1980). A more recent meta-analysis of psychotherapy effectiveness studies also confirms that psychotherapy helps (Shadish, Matt, Navarro, & Phillips, 2000).

Figure 10.1 Psychotherapy Versus No Treatment These two normal distributions summarize the data of a meta-analysis of 475 studies on the effectiveness of psychotherapy. They show that psychotherapy is effective—the average psychotherapy client was better off than 80 percent of the people not receiving therapy. (Adapted from Smith, Glass, & Miller, 1980.)

Figure 10.1 Psychotherapy Versus No Treatment These two normal distributions summarize the data of a meta-analysis of 475 studies on the effectiveness of psychotherapy. They show that psychotherapy is effective—the average psychotherapy client was better off than 80 percent of the people not receiving therapy. (Adapted from Smith, Glass, & Miller, 1980.)No one particular type of psychotherapy, is superior to all of the others. Some types of psychotherapy do, however, seem to be more effective in treating particular disorders. For example, behavioral therapies have been very successful in treating phobias and other anxiety disorders. Also, cognitive therapies tend to be very effective in treating depressive disorders. None of the psychotherapies, however, are very successful in treating schizophrenia.

Section Summary

There are two major categories of therapy: biomedical and psychological. Biomedical therapy involves the use of biological interventions, such as drugs, to treat disorders. Psychotherapy involves the use of psychological interventions to treat disorders. Psychotherapy is what we normally think of as therapy. In psychotherapy, there is an interaction between the person and the therapist. In biomedical therapy, the interaction is biological. There are three major types of biomedical therapy—drug therapy, shock therapy, and psychosurgery. There are four major types of psychotherapy—psychoanalytic, humanistic, behavioral, and cognitive.

The major medications are lithium, antidepressant drugs, antianxiety drugs, and antipsychotic drugs. Lithium, a naturally occurring mineral salt, is the main treatment for bipolar disorder. There are four types of antidepressants—MAO inhibitors, tricyclics, SSRIs, and SSNRIs. SSRIs, which work by selectively blocking the reuptake of serotonin, are prescribed most often. Antianxiety drugs are in a class of drugs called benzodiazepines; they reduce anxiety by stimulating GABA activity that inhibits the anxiety.

There are two types of antipsychotic drugs—traditional (those developed from the 1950s through the 1980s) and new generation (developed since the 1990s). The traditional antipsychotic drugs block receptor sites for dopamine, which globally lowers dopamine activity. Because of this, these traditional drugs produce side effects in motor movement that are similar to the movement problems of Parkinson’s disease. In addition, there is a long-term-use side effect of traditional antipsychotic drugs, tardive dyskinesia, in which the person has uncontrollable facial movements. The new generation drugs do not have these side effects, but they do have to be monitored very carefully because of other dangerous side effects. Such monitoring is expensive; therefore, traditional antipsychotic drugs are often prescribed instead.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) that involves electrically inducing a brief brain seizure is used almost exclusively to treat severe depression. We do not know how or why this therapy works, but it is a valuable treatment for severely depressed people who have not responded to other types of treatment because it leads to somewhat faster improvement than antidepressant drugs. Given its nature, however, ECT remains shrouded in controversy. An alternative neurostimulation therapy for the severely depressed, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), is not as controversial as ECT and does not produce any major side effects, but more research on its effectiveness is needed.

Even more controversial is psychosurgery, in which specific areas in the brain are actually destroyed. The most famous type of psychosurgery is the lobotomy, in which the neuronal connections of the frontal lobes to lower areas in the brain are severed. No good evidence for why such operations should work or that they did was ever put forth. The arrival of antipsychotic drugs in the 1950s replaced the lobotomy as the main treatment for schizophrenia. Psychosurgery is still around, but it is very different from what it once was and is used very infrequently, only when all other treatments have failed.

Psychotherapies can be categorized into two types—insight or action. Psychoanalytic and humanistic therapies are insight therapies; they focus on the person achieving insight into the causes of her behavior and thinking. Behavioral and cognitive therapies are action therapies; they focus on the actions of the person in changing her behavior and ways of thinking. The main goal of psychoanalysis, as developed by Freud, is for the therapist to uncover the unconscious sources of the person’s problems by interpreting the person’s free associations, dreams, resistances, and transferences. The therapist then helps the person to gain insight into the unconscious sources of her problem with this interpretation. Such classical psychoanalysis takes a long time; therefore, contemporary psychoanalytic therapists take a more direct and interactive role, emphasizing the present more than the past in order to shorten the period of therapy.

The most influential humanistic therapy is Rogers’s client-centered therapy in which the therapist uses unconditional positive regard, genuineness, and empathy to help the person to gain insight into her true self-concept and get on the path to self-actualization. The therapy is client-centered, and the client decides the direction of each session. The therapist’s main task is to create the conditions that allow the client to discover her true feelings and self-concept.

In behavioral therapies, the therapist uses the principles of classical and operant conditioning to change the person’s behavior from maladaptive to adaptive. The assumption is that the behavioral symptoms are the problem. These behaviors were learned; therefore, they need to be unlearned and more adaptive behaviors learned. Counterconditioning exposure therapies, such as systematic desensitization, virtual reality therapy, and flooding, have been especially effective in treating anxiety disorders such as phobias. Instead of changing the person’s behavior, the cognitive therapist attempts to change the person’s thinking from maladaptive to adaptive. Two major kinds of cognitive therapy are Ellis’s rational-emotive therapy and Beck’s cognitive therapy. Both have the same therapeutic goal—changing the person’s thinking to be more rational—but the therapeutic styles are very different. Rational-emotive therapy is far more confrontational and direct in its approach. Regardless, both have been very successful in treating major depressive disorders.

Using meta-analysis, a statistical technique that pools the results from many separate experimental studies on the same question into one analysis to determine whether there is an overall effect, researchers have concluded that psychotherapy is more effective than no therapy. There is no one particular type of psychotherapy that is best for all disorders, however. Rather, some types of psychotherapy seem more effective in treating particular disorders. For example, behavioral therapies tend to be effective in treating anxiety disorders, and cognitive therapies more effective in treating depression.

Concept Check | 3

Explain the difference between biomedical therapy and psychotherapy.

Explain the difference between biomedical therapy and psychotherapy.In biomedical therapy, there is a direct biological intervention—via drugs or ECT, which has an impact on the biochemistry of the nervous system, or psychosurgery, in which part of the brain is actually destroyed. There is no direct impact on the client’s biology in psychotherapy. Psychological interventions (talk therapies) are used to treat disorders. However, successful psychotherapy may indirectly lead to biological changes in the client’s neurochemistry through more positive thinking.

Explain how the neurogenesis theory of depression could be considered a biopsychosocial explanation.

Explain how the neurogenesis theory of depression could be considered a biopsychosocial explanation.The neurogenesis theory of depression can be considered a biopsychosocial explanation, because both biological and psychological factors can have an impact on the neurogenesis process that is assumed to eliminate the depression. Antidepressant drugs with their antagonistic effects on serotonin and norepinephrine are good examples of possible biological factors, and the positive thinking produced by cognitive psychotherapy is a good example of a psychological factor.

Explain why the psychoanalyst can be thought of as a detective.

Explain why the psychoanalyst can be thought of as a detective.A psychoanalyst can be thought of as a detective, because she has to interpret many clues to the client’s problem. Discovering the client’s problem is like solving a case. The sources of the psychoanalyst’s clues are free association data, resistances, dream analysis, and transferences. The therapist uses these clues to interpret the person’s problem (solve the case) and then uses this interpretation to help the person gain insight into the source of his problem.

Explain the difference between behavioral therapy and cognitive therapy.

Explain the difference between behavioral therapy and cognitive therapy.Both of these types of psychotherapies are very direct in their approach. However, behavioral therapies assume that the client’s behavior is maladaptive and needs to be replaced with more adaptive behavior. Cognitive therapies instead hold that the client’s thinking is maladaptive and needs to be replaced with more adaptive thinking. In brief, the behavioral therapist works to change the client’s behavior, and the cognitive therapist works to change the client’s thinking.

Explain why a control for spontaneous remission must be included in any assessment of the effectiveness of psychotherapy.

Explain why a control for spontaneous remission must be included in any assessment of the effectiveness of psychotherapy.Spontaneous remission is when a person gets better with the passage of time without receiving any therapy. Thus, if it were not considered when the effectiveness of psychotherapy is being evaluated, the researcher might incorrectly assume that the improvement was due to the psychotherapy and not to spontaneous remission. This is why the improvement in wellness for the psychotherapy group must be significantly (statistically) greater than the improvement for the spontaneous remission control group. If it is, then the psychotherapy has produced improvement that cannot be due to just spontaneous remission.