The Psychoanalytic Approach to Personality

Freud developed his landmark psychoanalytic theory of personality starting in the late nineteenth century and continuing until his death in 1939. His first solo authored book, The Interpretation of Dreams, came out in 1900 and was followed by more than 20 other volumes. Freud’s psychoanalytic theory has been so influential that many of its important concepts—id, ego, defense mechanisms, Oedipus conflict, Freudian slip, and so on—have become part of our culture. Freud’s theory is usually referred to as classical psychoanalytic theory. This distinguishes it from both other psychoanalytic theories developed by Freud’s disciples and from contemporary psychodynamic theories (personality theories with a psychoanalytic base). The theories of Freud’s disciples are usually called neo-Freudian theories (“neo” is Greek for new). The neo-Freudian theories shared many assumptions with classical Freudian theory, but differed in one or more important ways. Modern psychodynamic theories have veered even further away from Freud’s original work. They still emphasize the importance of childhood experiences, unconscious thought processes, and addressing inner conflicts, but they don’t use much of Freud’s terminology nor do they focus on sex as the origin of personality. In this chapter, we will first discuss Freud’s classical psychoanalytic theory and then describe some prominent neo-Freudian theories of personality.

Freudian Classical Psychoanalytic Theory of Personality

Freud received a medical degree from the University of Vienna and established a practice as a clinical neurologist treating patients with emotional disorders. Through his work with these patients, Freud became convinced that sex was a primary cause of emotional problems (Freud, 1905/1953b). Sex, including infantile sexuality, became a critical component of his personality theory (Freud 1900/1953a, 1901/1960, 1916 & 1917/1963, 1933/1964). To help you understand Freud’s theory, we will consider its three main elements: (1) different levels of awareness, with an emphasis on the role of the unconscious; (2) the dynamic interplay between the three parts of the personality—id, ego, and superego; and (3) the psychosexual stage theory of personality development.

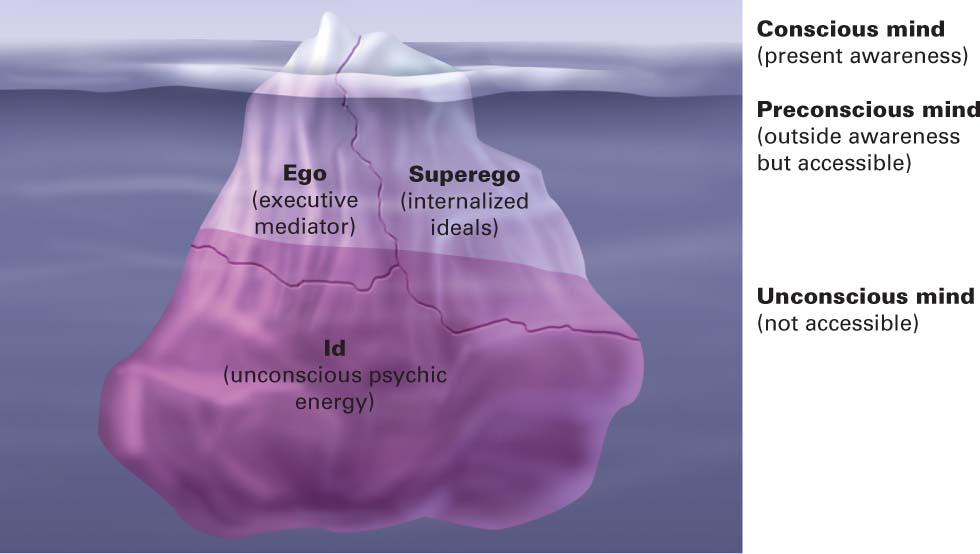

Freud’s three levels of awareness. According to Freud, the mind has three levels of awareness—the conscious, the preconscious, and the unconscious. This three-part division of awareness is Freud’s famous iceberg model of the mind (Figure 8.1). The iceberg’s visible tip above the surface is the conscious mind, what you are presently aware of. In memory terms, this is your short-term memory. It is what you are thinking about right now. The part of the iceberg just beneath the surface is the preconscious mind, what is stored in your memory that you are not presently aware of but can gain access to. In memory terms, this is your long-term memory. For example, you are not presently thinking about your birthday, but if I asked you what your birthday was, you could bring that information from the preconscious to the conscious level of awareness.

Figure 8.1 Freud’s Iceberg Model of the Mind In the iceberg model of the mind, the small part above water is our conscious mind; the part just below the surface is the preconscious; and the major portion, hidden below water, is the unconscious. A person has access only to the conscious and preconscious levels of awareness. The conscious is what the person is presently thinking about, and the preconscious is information that the person could bring into conscious awareness.

Figure 8.1 Freud’s Iceberg Model of the Mind In the iceberg model of the mind, the small part above water is our conscious mind; the part just below the surface is the preconscious; and the major portion, hidden below water, is the unconscious. A person has access only to the conscious and preconscious levels of awareness. The conscious is what the person is presently thinking about, and the preconscious is information that the person could bring into conscious awareness.It is the third level of awareness, the unconscious, that Freud emphasized in his personality theory. In Freud’s iceberg model, the large base of the iceberg that is hidden deep beneath the surface is the unconscious mind, the part of our mind that we cannot freely access. Freud believed this area contains the primary motivations for all of our actions and feelings, including our biological instinctual drives (such as for food and sex) and our repressed unacceptable thoughts, memories, and feelings, especially unresolved conflicts from our early childhood experiences. To better understand the role of these motivations, we need to become familiar with Freud’s theory of the personality structure and his psychosexual stage theory of personality development.

Freud’s three-part personality structure. Freud divided the personality structure into three parts—id, ego, and superego. These are mental processes or systems and not actual physical structures. Freud believed that personality is the product of the dynamic interaction of these three systems. The id is the original personality, the only part present at birth and the part out of which the other two parts of our personality emerge. As you can see in Figure 8.1, the id resides entirely in the unconscious part of the mind. The id includes biological instinctual drives, the primitive parts of personality located in the unconscious. Freud grouped these instinctual drives into life instincts (survival, reproduction, and pleasure drives such as for food, water, and sex) and death instincts (destructive and aggressive drives that are detrimental to survival). Freud downplayed the death instincts in his theory and emphasized the life instincts, especially sex. The id contains psychic energy, which attempts to satisfy these instinctual drives according to the pleasure principle—immediate gratification for these drives without concern for the consequences. Thus, the id is like a spoiled child, totally self-centered and focused on satisfying these drives. For example, if you’re hungry, the id, using the pleasure principle, would lead you to take any food that is available without concern for whom it belongs to.

Obviously the id cannot operate totally unchecked. We cannot go around taking anything we want to satisfy the id’s drives. Our behavior is constrained by social norms and laws. We have to buy food from markets, stores, and restaurants. Our personality develops as we find ways to meet our needs within these social constraints. The second part of the personality structure, the ego, starts developing during the first year or so of life in order to find realistic outlets for the id’s needs. Because the ego emerges out of the id, it derives its psychic energy from the id. The ego has the task of protecting the personality while ensuring that the id’s drives are satisfied.

The ego, then, is the pragmatic part of the personality; it weighs the risks of an action before acting. The ego uses the reality principle—finding gratification for instinctual drives within the constraints of reality (the norms and laws of society). In order to do this, the ego spans all three levels of awareness (see Figure 8.1). Because of its ties to the id, part of the ego must be located in the unconscious; and because of its ties to reality (the external world), part of it must be in the conscious and preconscious. The ego uses memory and conscious thought processes, such as reasoning, to carry out its job.

The ego functions as the manager or executive of the personality. It must mediate not only between the instinctual drives of the id and reality but also between these drives and the third part of the personality structure, the superego, which represents the conscience and idealized standards of behavior in a particular culture. The superego develops during childhood and, like the ego, develops from id energy and spans all levels of awareness. It tells the ego how one ought to act. Thus, the superego might be said to act in accordance with a morality principle. For example, if the id hunger drive demanded satisfaction, and the ego had found a way to steal some food without being caught, the superego would threaten to overwhelm the individual with guilt and shame for such an act. Inevitably, the demands of the superego and the id will come into conflict, and the ego will have to resolve this turmoil within the constraints of reality. This is not an easy task.

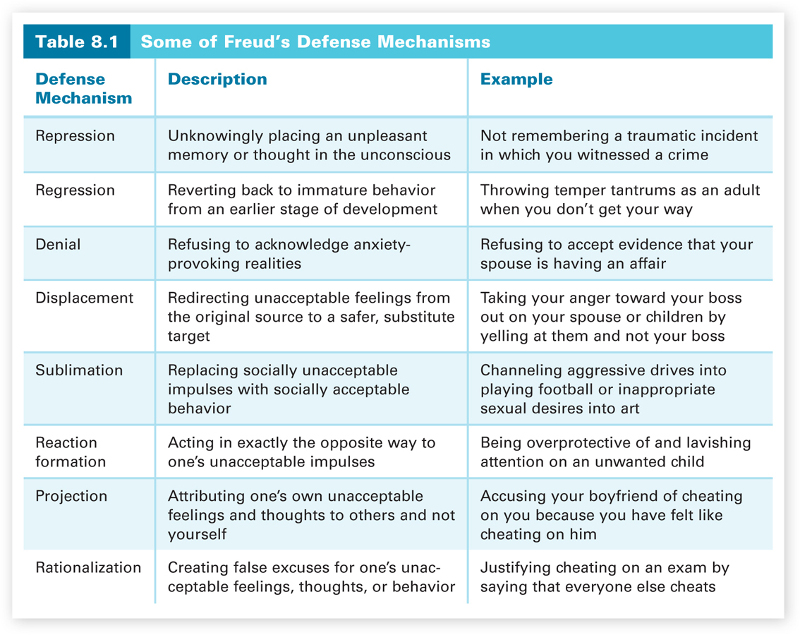

Here is why the ego’s job is so difficult. Imagine that your parents are making conflicting demands on you. For example, when you were deciding which college to attend, let’s say your father wanted you to attend a state university and your mother wanted you to attend her private college alma mater. Imagine also that your boyfriend or girlfriend is adding a third level of conflicting demands (wanting to go to school together at the local community college). You want to satisfy all three, but because the demands are conflicting, it is not possible. You get anxious, because there is no good resolution to the conflict. This is what often happens to the ego in its role as mediator between its three masters (id, superego, and reality). To prevent being overcome with anxiety, the ego uses what Freud called defense mechanisms, processes that distort reality and protect us from anxiety (Freud, 1936). The ego has many different defense mechanisms available for such self-deception, including repression, denial, displacement, and rationalization. Table 8.1 provides descriptions and examples of several defense mechanisms.

Freud thought of repression as the primary defense mechanism. He believed that repression, along with other defense mechanisms, helps us deal with anxiety. If we are unaware of unacceptable feelings, memories, and thoughts (they have been put in our unconscious), then we cannot be anxious about them. But it is important to remember that Freud proposed that repression occurs automatically—without conscious awareness. Once repressed, we have no conscious memory that the thought, event, or impulse ever existed. Although defense mechanisms may indeed help us with anxiety, we now know that we may also become dependent upon them. They may prevent us from facing our problems and dealing with them. The best defense mechanism may be using no defense mechanisms. Facing up to problems may allow us to see that reality is not as bad as we thought, and that consciously working to change reality is more beneficial than distorting it.

Freud believed that unhealthy personalities develop not only when we become too dependent upon defense mechanisms, but also when the id or superego is unusually strong or the ego is unusually weak. In such cases, the ego cannot control the other two processes. For example, a person with a weak ego would not be able to hold the id drives in check, possibly leading to a self-centered personality. Or, a person with an overly strong superego would be too concerned with morality, possibly leading to a guilt-ridden personality. A healthy personality, according to Freud’s personality structure, is one in which none of the three personality systems (id, ego, and superego) is dominating, allowing the three systems to interact in a relatively harmonious way.

In addition to imbalances between the three personality parts, Freud stressed the importance of our early childhood experiences in determining our adult personality traits. In fact, he thought that our experiences during the first six years or so of life were critical in the development of our adult personality. To understand exactly how Freud proposed that early childhood experiences impact personality, we now turn to a consideration of his psychosexual stage theory.

Freud’s psychosexual stage theory. Freud did not spend much time observing children to help him develop his psychosexual stage theory of personality development. Freud’s psychosexual stage theory was developed chiefly from his own childhood memories and from his years of interactions with his patients and their case studies, which included their childhood memories.

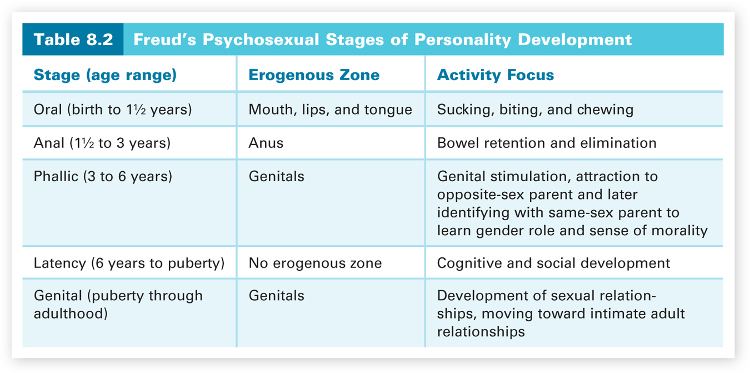

Two key concepts in his psychosexual theory are erogenous zone and fixation. An erogenous zone is the area of the body where the id’s pleasure-seeking psychic energy is focused during a particular stage of psychosexual development. The erogenous zone feels good when stimulated in various ways. Thus, the erogenous zones are the body areas where instinctual satisfaction can be obtained. Each of Freud’s psychosexual stages is named after the erogenous zone involved, and a change in location of the erogenous zone designates the beginning of a new stage. For example, the first stage is called the oral stage, and the erogenous zone is the mouth area, so pleasure is derived from oral activities such as sucking. Freud proposed five stages—oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital. They are outlined in Table 8.2, with the erogenous zone for each stage indicated.

Freud’s concept of fixation is important in understanding how he believed our childhood experiences impact our adult personality. A fixation occurs when a portion of the id’s pleasure-seeking energy remains in an earlier psychosexual stage because of excessive or insufficient gratification of our instinctual needs during that stage of development. A person who is overindulged will want to stay and not move on, while a person who is frustrated has difficulty moving on because his needs are not met. The stronger the fixation, the more of the id’s pleasure-seeking energy remains in that stage. Such fixations continue throughout the person’s life and impact his behavior and personality traits. For example, a person who is fixated in the oral stage because of excessive gratification may become overly concerned with oral activities such as smoking, eating, and drinking. Because his oral needs have been overindulged, such a person may continue to depend upon others to meet his needs and thus have a dependent personality. Such a person is also likely to be gullible or willing to “swallow” anything. We will consider some other examples of fixation as we describe the five stages.

In the oral stage (from birth to 18 months), the erogenous zones are the mouth, lips, and tongue, and the child derives pleasure from oral activities such as sucking, biting, and chewing. As already pointed out, a fixation would lead to having a preoccupation with oral behaviors, such as smoking, gum chewing, overeating, or even talking too much. Freud himself had such a preoccupation with smoking. He smoked 20 or so cigars a day and had numerous operations for cancer in his mouth, which eventually led to his death (Larsen & Buss, 2000). Many other personality characteristics can also stem from oral fixations. For example, a fixation created by too little gratification might lead to an excessively mistrustful person. The deprived infant has presumably learned that the world cannot be trusted to provide for basic needs.

In the anal stage (from about 18 months to 3 years), the erogenous zone is the anus, and the child derives pleasure from stimulation of the anal region through having and withholding bowel movements. Toilet training and the issue of control are major concerns in this stage. Parents try to get the child to have self-control during toilet training. Freud believed that fixations during this stage depend upon how toilet training is approached by the parents. Such fixations can lead to two famous adult personalities, anal retentive and anal expulsive. Both are reactions to harsh toilet training in which the parents admonish and punish the child for failures. If the child reacts to this harsh toilet training by trying to get even with the parents and withholding bowel movements, an anal-retentive personality with the traits of orderliness, neatness, stinginess, and obstinacy develops. The anal-expulsive personality develops when children rebel against harsh training and have bowel movements whenever and wherever they please. Such people tend to be sloppy, disorderly, and possibly even destructive and cruel.

In the phallic stage (from age 3 to 6 years), the erogenous zone is located at the genitals, and the child derives pleasure from genital stimulation. According to Freud, there is much psychological conflict in this stage, including the Oedipus conflict for boys. In the Oedipus conflict, the little boy becomes sexually attracted to his mother and fears the father (his rival) will find out and castrate him. This parallels the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex, in which Oedipus unknowingly kills his father, marries his mother, and then realizes what he’s done and gouges his eyes out as punishment. Freud was much less confident about the existence of a comparable Electra conflict for girls, in which a girl is supposedly attracted to her father due to penis envy.

Freud believed that children, especially boys, resolve conflicts in this stage by repressing their desire for the opposite-sex parent and identifying with the same-sex parent. It is in this process of identification that Freud believed children adopt the characteristics of the same-sex parent and learn their gender roles. For example, a little boy would adopt the behaviors and attitudes of his father. According to Freud, unsuccessful resolution of this conflict would result in a child having a conflicted gender role, sexual relationship problems with the opposite sex, and possibly a homosexual orientation. It is also during this identification process that the superego develops, as a child learns his sense of morality by adopting the attitudes and values of his parents.

Freud considered the final two stages of his psychosexual theory the least important for personality development. He assumed that how a child progresses through the first three stages pretty much determined the child’s adult personality. In the latency stage (from about age 6 to puberty), there is no erogenous zone, sexual drives become less active, and the focus is on cognitive and social development. A child of this age is most interested in school, sports, hobbies, and in developing friendships with other children of the same sex. In the genital stage (from puberty through adulthood), the erogenous zone is at the genitals again, and Freud believed a person develops sexual relationships in a move toward intimate adult relationships.

Evaluation of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of personality. Freud’s ideas were controversial when he first proposed them and have remained controversial over the past century. Let’s consider some of the criticisms of his major concepts. First, consider Freud’s “unconscious” level of awareness. Because this concept is not accessible to anyone, it is impossible to examine scientifically and thus cannot be experimentally tested. We can’t observe and study a factor that we are not aware of. This criticism does not deny that unconscious processing greatly impacts thinking and behavior. On the contrary, it acknowledges that the impact is great. Think back to Chapter 3, on the human senses and perception, to Chapter 5, on memory, and to Chapter 6, on thinking. Our conscious level of awareness of these important processes is like Freud’s “tip of the iceberg.” We have learned, however, that this iceberg is not a storehouse of instinctual drives, conflicts, and repressed memories and desires as Freud proposed. It is the location of all of our cognitive processes and the knowledge base they use—the center of our information processing. Freud was correct in pointing to unconscious processing as crucial, but he was incorrect about its role and the nature of its importance.

Freud was also correct in pointing to the importance of early childhood experience, but he was again incorrect about the nature of its importance. There is little evidence that psychosexual stages impact development, but there is evidence that many of the concepts we discussed in the last chapter, such as the connection between the type of attachment an infant forms and parenting style, are important. What about Freud’s main defense mechanism, repression? Contemporary memory researchers think that it seldom, if ever, occurs (Holmes, 1990; Loftus & Ketcham, 1994; McNally, 2003). Remember the discussion of so-called recovered memories in Chapter 5, on memory? We understand today how Freud’s questioning during therapy may have created such “repressed” memories in his patients. Do the other defense mechanisms fare any better? There is evidence that we do use certain defense mechanisms to ward off anxiety, though we do not necessarily do so unconsciously.

We must remember that Freud started developing his theory over 100 years ago. Our world and the state of psychological research knowledge were very different then. So, it is not surprising that Freud’s theory doesn’t stand up very well today. What is surprising is that he could develop a theory from such a scant database, a theory that has had such great impact on our thinking and culture. In 1999 he was on the cover of a special issue of Time magazine commemorating the 100 greatest thinkers and scientists of the twentieth century. We can only speculate on what his theory would be like if he had started in 1990 rather than 1890.

Neo-Freudian Theories of Personality

Even Freud’s own circle of psychoanalysts disagreed with him on some aspects of his theory. These disagreements led them to develop psychoanalytic theories that accepted most of Freud’s basic ideas, but differed from Freud in one or more important ways. They became known as neo-Freudian psychoanalytic theorists. In addition to Erik Erikson, whose psychosocial stage theory of development was described in the last chapter, the major neo-Freudian theorists were Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, and Karen Horney (pronounced HORN-eye). In general, these three neo-Freudian theorists, like Erikson, thought that Freud placed too much importance on psychosexual development and sexual drives and not enough emphasis on social and cultural influences on the development of personality. We discuss Jung first because, other than Freud, he is the best-known psychoanalytic theorist.

Jung’s collective unconscious.

Carl Jung extended Freud’s notion of the unconscious to include not only the personal unconscious—each individual’s instinctual drives and repressed memories and conflicts—but also the collective unconscious, the accumulated universal experiences of humankind. Each of us inherits this same cumulative storehouse of all human experience that is manifested in archetypes—symbolic images of all of the important themes in the history of humankind (such as God, the mother, and the hero). The archetypes in the collective unconscious are why myths and legends in very diverse cultures tend to have common themes. In addition to these shared universal archetypes, each of us inherits more specific ones that guide our individual personality development. Jung’s theoretical concepts are rather mystical and not really scientific. His interest in the mystical side of life greatly influenced his theory, and his concepts, such as the collective unconscious and archetypes, are beyond empirical verification. These symbolic, mystical aspects of Jung’s theory may be why it has been more popular in the fields of religion, anthropology, and literature than in psychology.

Personality psychologists, however, have pursued some other aspects of Jung’s theory. Most prominently, Jung proposed two main personality attitudes—extraversion and introversion. People’s attitudes focus them toward the external, objective world (extraversion) or toward the inner, subjective world (introversion). Along with these two general outlooks, Jung proposed four functions (or cognitive styles)—sensing and intuiting for gathering information and thinking and feeling for evaluating information. Across individuals, the development of these four functions varies, with one of them being dominant. These two attitudes and four functions lead to eight possible personality types. These eight types were the basis for a personality test, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, developed in the 1920s by Katherine Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Myers. This test has been the primary tool for research on Jung’s personality types, and it is still in use today (Myers & McCaulley, 1985). In addition, Jung’s two personality attitudes, extraversion and introversion, play a central role in contemporary trait theories of personality, which we will discuss in the last section of this chapter.

Adler’s striving for superiority. Another neo-Freudian theorist, Alfred Adler, disagreed with Freud’s assumption that the main motivation in personality development is the satisfaction of sexual urges. Adler thought that the main motivation was what he termed “striving for superiority,” the need to overcome the sense of inferiority that we feel as infants, given our totally helpless and dependent state. Adler believed that these feelings of inferiority serve as our basic motivation. They lead us to grow and strive toward success. A healthy person learns to cope with these feelings, becomes competent, and develops a sense of self-esteem. Parental love and support help a child overcome her initial feelings of inferiority. Adler used the phrase “inferiority complex” to describe the strong feelings felt by those who never overcome the initial feeling of inferiority. People with an inferiority complex often have unloving, neglectful, or indifferent parents. The complex leads to feelings of worthlessness and a mistrust of others. Adler also defined what he termed a “superiority complex,” an exaggerated opinion of one’s abilities. This leads to a self-centered, vain person.

Horney and the need for security.

Like Adler, Karen Horney focused on our early social experiences with our parents, not on instinctual biological drives. Unlike Adler, Horney’s focus was on dealing with our need for security rather than a sense of inferiority. Remember the importance of a secure attachment for infants that we discussed in the last chapter, on human development? According to Horney’s theory, a child’s caregivers must provide a sense of security for a healthy personality to develop. Children whose parents do not lead them to feel secure would suffer from what Horney called “basic anxiety,” a feeling of helplessness and insecurity in a hostile world. This basic anxiety about personal relationships may lead to neurotic behavior and a disordered personality (Horney, 1937). Horney differentiated three neurotic personality patterns—moving toward people (a compliant, submissive person), moving against people (an aggressive, domineering person), and moving away from people (a detached, aloof person). This focus of Horney and other neo-Freudian theorists on the importance of interpersonal relationships, both in childhood and in adulthood, continues in contemporary psychodynamic theory (Westen, 1998).

Section Summary

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Freud developed his psychoanalytic theory of personality. He divided the mind into three levels of awareness—conscious, preconscious, and unconscious—with the unconscious (the part that we cannot become aware of) being the most important in his theory. It is the unconscious that contains life and death instinctual drives, the primary motivators for all of our actions and feelings. In addition, there are three parts of the personality structure—the id (which contains the instinctual drives and is located totally in the unconscious), the ego (the manager of the personality), and the superego (our conscience and sense of morality). The ego and the superego span all three levels of awareness. The ego attempts to find gratification for the id’s instinctual drives within the constraints of the superego and reality (societal laws and norms). When the ego cannot achieve this difficult task, we become anxious. To combat such anxiety, Freud suggested that we use defense mechanisms, which protect us from anxiety by distorting reality. The primary defense mechanism is repression, unknowingly placing an unpleasant memory or thought in the unconscious, where it cannot bother us.

Freud also emphasized the importance of early childhood experience in his theory. He proposed that how successfully a child progresses through the early psychosexual stages greatly impacts his personality development. Freud proposed five psychosexual stages, with the first three being most important to our personality development. The stages—in order, with the erogenous zone (pleasure center) indicated for that stage—are oral (mouth), anal (anus), phallic (genitals), latency (no erogenous zone), and genital (genitals). A fixation, which occurs when some of the id’s pleasure-seeking energies remain in a stage because of excessive or insufficient gratification, influences a person’s behavior and personality for the rest of his life. For example, a person with an oral fixation will seek physical pleasure from oral activities and may be overly dependent and gullible. The important Oedipus conflict for boys (and Electra conflict for girls) in which the child is attracted to the opposite-sex parent occurs in the phallic stage of development from about age 3 to age 6. Resolution of this conflict leads the child to identify with the same-sex parent and learn his or her proper gender role and sense of morality.

Neo-Freudian theorists were psychoanalytic theorists who agreed with much of Freud’s theory but disagreed with some of Freud’s key assumptions, which led them to develop their own versions of psychoanalytic theory. For example, Carl Jung theorized that, in addition to the personal unconscious, we have a collective unconscious that contains the accumulated experiences of humankind. Alfred Adler proposed that the main motivation was not sexual, but rather a striving for superiority in which we must overcome the sense of inferiority that we feel as infants. Failure to do so leads to an inferiority complex. Karen Horney focused her attention on our need for security as infants, rather than our sense of inferiority. She argued that if our caregivers do not help us to gain a feeling of security, we suffer from a sense of basic anxiety, which leads to various types of personality problems.

Concept Check | 1

Explain, according to Freudian theory, why the ego has such a difficult job.

Explain, according to Freudian theory, why the ego has such a difficult job.According to Freud, the ego is the executive of the personality in that it must find acceptable ways within reality (society’s norms) and the constraints of the superego to satisfy the instinctual drives of the id. Finding such ways is not easy, and the ego may not be able to do its job.

Explain the difference between Freud’s two defense mechanisms—reaction formation and projection.

Explain the difference between Freud’s two defense mechanisms—reaction formation and projection.In reaction formation, the ego transforms the unacceptable impulses and behavior into their opposites; in projection they are projected onto other people. For example, consider thoughts of homosexuality in a man. In reaction formation, the man would become just the opposite in his behavior, romantically overly interested in the opposite sex. However, in projection, the homosexual feelings would be projected onto other men. He would see homosexual tendencies in other men and think they were gay, but he would not think this about himself.

Explain how fixations in psychosexual development affect adult behavior and personality.

Explain how fixations in psychosexual development affect adult behavior and personality.According to Freud, as a child progresses through the first three psychosexual stages (oral, anal, and phallic), he may become fixated in a stage when there is an unresolved conflict in that stage. If fixated, part of the id’s pleasure-seeking energy remains at that erogenous zone and continues throughout a person’s life. Thus, it will show up in the child’s adult personality. For example, anal fixations will lead to the anal retentive or expulsive personality types.