Trait Theories of Personality and Personality Assessment

As we pointed out at the beginning of this chapter, personality traits are internally based, relatively stable characteristics that define an individual’s personality. Traits are continuous dimensions, and people vary from each other along the dimensions for each of the various traits that make up personality. But what are the specific traits that make up human personality? Think about all of the adjectives that can describe a person. There are thousands, but this doesn’t mean that thousands of traits are necessary to describe human personality. Trait theories attempt to discover exactly how many traits are necessary. You will be surprised to find out that the major trait theories propose that this number is rather small. How are such numbers derived?

Trait theorists use factor analysis (and other statistical techniques) to tell them how many basic personality factors (or traits) are needed to describe human personality, as well as what these factors are. Remember, factor analysis is the statistical tool from Chapter 6 that we used to discuss the question of whether intelligence was one ability or many. Factor analysis identifies clusters of test items (in this case, on a personality test) that measure the same factor (trait). Allport and Odbert (1936) did the initial analyses, starting with 18,000 words that could be used to describe humans. Their analyses left them with around 200 clusters. Later trait researchers have reduced this number considerably; the consensus number of necessary traits is only five.

In this section, we’ll consider two major trait theories that were developed using factor analysis, Hans Eysenck’s three-factor theory and the Five Factor Model of personality. We’ll also discuss personality assessment, because personality tests are often developed to assess a theorist’s proposed basic traits. The major uses for personality tests, however, are to diagnose personality problems, to aid in counseling, and to aid in making personnel decisions; therefore, we’ll focus our discussion on the two main types of personality tests used, personality inventories and projective tests.

Trait Theories of Personality

According to trait theorists, basic traits are the building blocks of personality. Each trait is a dimension, a continuum ranging from one extreme of the dimension to the other. A person can fall at either extreme or anywhere in between on the continuum. An individual’s personality stems from the amount of each trait that he has. This is analogous to the trichromatic theory of color vision that we discussed in Chapter 3. Remember that according to the trichromatic theory, all of the thousands of different colors that we can perceive stem from different proportions of the three primaries (red, green, and blue). In trait theories, all personalities stem from different proportions of the basic traits.

The number and kind of personality traits. Different theorists have come up with different answers to the question of how many basic personality traits there are and even what they are. For example, using factor analysis, early trait researcher Raymond Cattell found that 16 traits were necessary (Cattell, 1950, 1965). More recently, Hans Eysenck, also using factor analysis, has argued for only three trait dimensions (Eysenck, 1982; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985). There are two major reasons for the different numbers—the level of abstraction and the type of data. First, the number of traits depends upon the level of abstraction in the factor analysis. For example, if you factored Cattell’s 16 traits further, you would probably get something closer to Eysenck’s three higher-order factors (Digman, 1990). This means that Eysenck’s theory is at a more general and inclusive level of abstraction than Cattell’s theory. More important, the number of traits depends upon which databases and what types of data different theorists use in their factor analysis. Different data could, of course, lead to different traits, as well as a different number of traits. Surprisingly, contemporary trait researchers have reached something of a consensus about the number and the nature of the basic personality traits. The three traits proposed by Eysenck are insufficient, and the 16-factor theory of Cattell is needlessly complex (McCrae, 2011). The consensus number is five, and these five traits (or factors) are referred to as the “Big Five.” First, we’ll discuss Eysenck’s three-factor theory, because he (unlike most trait theorists) proposes actual causal explanations for his traits, and then we’ll discuss the Five Factor Model of personality.

Eysenck’s three-factor theory. Hans Eysenck’s three trait dimensions are extraversion–introversion, neuroticism–emotional stability, and psychoticism–impulse control. These are continuous dimensions, with extraversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism, respectively, at the high ends. Eysenck argues that these three traits are determined by heredity and proposes a biological basis for each one of them (Eysenck, 1990, 1997).

Extraversion and introversion have their normal meanings, indicating differences in sociability. Extraverts are gregarious, outgoing people with lots of friends; introverts are those who are quiet, are more introspective, and tend to avoid social interaction. For example, in a study of students going off to college, the extraverted ones struck up new friendships more quickly than the introverted ones (Asendorpf & Wilpers, 1998). The proposed biological basis for the extraversion–introversion trait is level of cortical arousal (neuronal activity). According to Eysenck, an introvert has a higher normal level of arousal in the brain than an extravert. The brains of introverts are more active. This means that an extravert has to seek out external stimulation in order to raise the level of arousal in the brain to a more optimal level.

People who are high on the neuroticism–emotional stability dimension tend to be overly anxious, emotionally unstable, and easily upset; people who are low on this dimension tend to be calm and emotionally stable. People high on this dimension experience more lingering negative emotional states in their daily lives and suffer from higher rates of anxiety and depression (Widiger, 2009). Eysenck proposes differences in the sympathetic nervous system as the basis for this trait. People high on the neuroticism trait have more reactive sympathetic nervous systems.

The psychoticism–impulse control trait dimension is concerned with aggressiveness, impulsiveness, empathy (seeing situations from other people’s perspectives), and antisocial behavior. Eysenck assumes that a high level of testosterone and a low level of MAO, a neurotransmitter inhibitor, lead to behavior that is aggressive, impulsive, antisocial, and lacking in empathy.

Eysenck’s very specific biological assumptions make his theory rather easy to test experimentally. Thus, it has generated much research, and the findings have been somewhat supportive. However, most research seems to indicate that five factors, rather than three, are necessary (Funder, 2001; Goldberg, 1990; John, 1990; McCrae & Costa, 2003; Wiggins, 1996). Unlike Eysenck, five-factor theorists use only the high end of each trait dimension to identify the factor. So how do you get to five from Eysenck’s three factors? Eysenck’s extraversion and neuroticism factors are retained, but his psychoticism factor is broken into two parts, conscientiousness and agreeableness, and an openness factor is added (Nettle, 2007). Now let’s take a closer look at the Five Factor Model of personality.

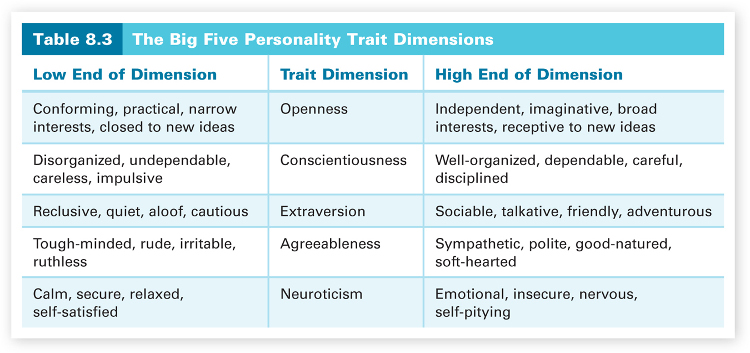

The Five Factor Model of personality. The Five Factor Model of personality was formulated by Robert McCrae and Paul Costa (McCrae & Costa, 1999). The descriptions of the high and low ends of the five trait dimensions (called the Big Five) given in Table 8.3 will provide you with a brief overview of the five proposed factors. To remember the five factors, try forming acronyms using their first letters. Order is not important. You could use OCEAN (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism) or CANOE (Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, Neuroticism, Openness, and Extraversion). Similarly, you might use PEN to remember Eysenck’s three traits (Psychoticism, Extraversion, and Neuroticism).

We have already briefly discussed extraversion and neuroticism when we described Eysenck’s trait theory, so let’s see what conscientiousness, openness, and agreeableness entail and what real-world behaviors they are related to. Conscientiousness is a tendency to show self-discipline, dependability, and organization and to prefer planned versus spontaneous behavior. Conscientiousness is positively correlated with high school and college GPAs (Noftle & Robins, 2007) and is linked to living a healthier and longer life (Bogg & Roberts, 2004; Kern & Friedman, 2008; Roberts, Smith, Jackson, & Edmonds, 2009). Openness (often referred to as openness to experience) reflects a person’s degree of intellectual curiosity, creativity, and preference for novelty and variety. A person who scores high on the openness factor is willing to try new things, is imaginative, and tends to have liberal values and be open-minded (McCrae & Sutin, 2009). High scorers on openness also tend to score high on intelligence tests and the SAT Verbal test (Noftle & Robins, 2007; Sharp, Reynolds, Pedersen, & Gatz, 2010). Agreeableness is the tendency to be compassionate and cooperative rather than suspicious and antagonistic toward others. People who score high on the agreeableness factor tend to be friendly, altruistic, empathetic, and to have an optimistic view of human nature (Graziano, Habashi, Sheese, & Tobin, 2007). Variation in agreeableness also correlates well with the variation in social-cognitive theory of mind functioning in adults, with high scorers performing better on theory of mind tasks (Nettle & Liddle, 2008).

According to Costa and McCrae (1993, p. 302), the Five Factor Model “is the Christmas tree on which findings of stability, heritability, consensual validation, cross-cultural invariance, and predictive validity are hung like ornaments.” Indeed, recent research indicates that these five factors may be universal. They have been observed across gender, and in many diverse languages (such as English, Korean, and Turkish) and cultures (including American, Hispanic, European, African, and Asian cultures), and not just in Western industrialized societies (McCrae & Costa, 1997, 2001; McCrae et al., 2004; Schmidt, Allik, McCrae, & Benet-Martinez, 2007). In addition, research has found that the Big Five factors have about a 50 percent heritability rate across several cultures (Bouchard & McGue, 2003; Jang et al; 2006; Loehlin, 1992; Loehlin, McCrae, Costa, & John, 1998), indicating a strong genetic basis. The Big Five factors also seem consistent from about age 30 to late adulthood (Costa & McCrae, 1988) and are generally consistent across situations (Buss, 2001). Given their general consistency over time and situations, some psychologists think that each trait must be associated with a specific pattern of brain behavior or structure (e.g., Canli, 2006). In fact, DeYoung et al. (2010) have proposed a theory of the biological bases of the Big Five personality factors and found supporting evidence using magnetic resonance imaging for four of the five factors.

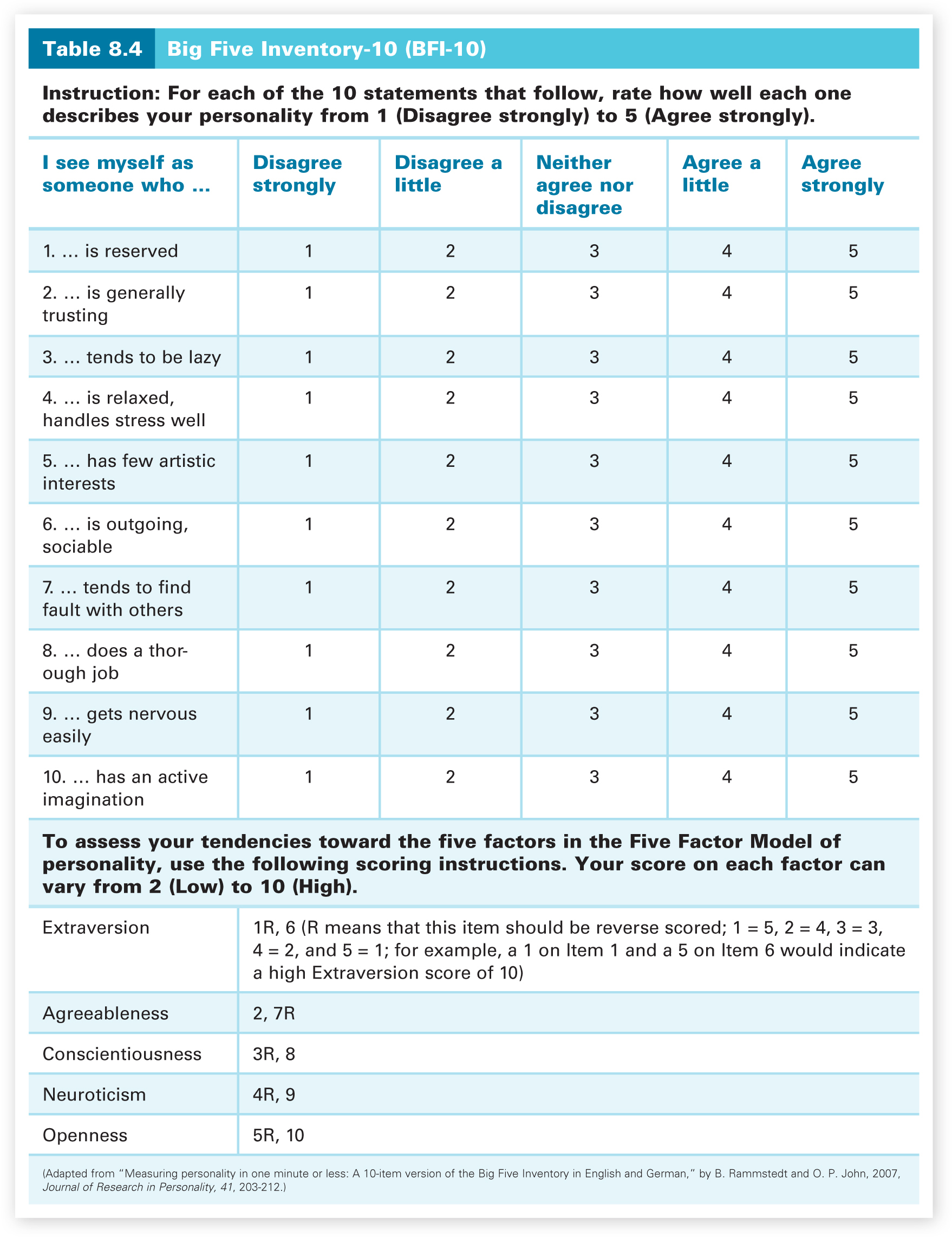

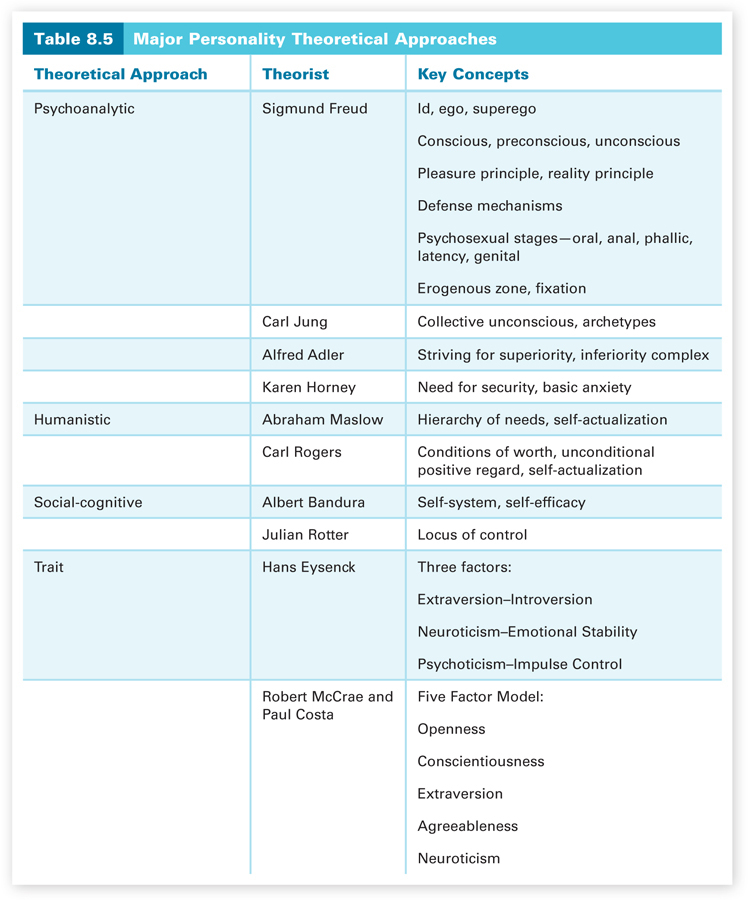

Given the importance of the Big Five factors, Robert McCrae and Paul Costa have developed personality inventory assessment instruments, the NEO-PI-R, the NEO-PI-3, and the NEO-FFI, which provide personality profiles of these five factors (Costa & McCrae, 1985, 1992, 2008; McCrae, Costa, & Martin, 2005). Rammstedt and John (2007) have developed a 10-item, one-minute-or-less measure of the NEO-PI-R that retains significant levels of reliability and validity. An adapted version of their test is given in Table 8.4. Go ahead and take the test. It will help you to get a better understanding of not only the Big Five personality traits but also personality inventories in general and how they differ from the better-known projective personality tests. After taking the test and before going on to read about personality assessment, review Table 8.5, which summarizes all of the theoretical approaches to personality that we have discussed. Make sure that you know and understand the various theorists and their key concepts.

Personality Assessment

Personality tests are a major tool in personality trait research, but the main uses of personality tests are to aid in diagnosing people with problems, in counseling, and in making personnel decisions. There are many types of personality tests, but we will focus on two, personality inventories and projective tests. Most of the other types of personality tests have more limited use. For example, Carl Rogers and humanistic psychologists have developed questionnaires that only address the self-concept, and Julian Rotter has developed a test that specifically assesses locus of control.

Personality inventories. A personality inventory is designed to measure multiple traits or, in some cases, disorders. It is a series of questions or statements for which the test taker must indicate whether they apply to him or not. The typical response format is True–False or Yes–No. Often a third response category of Can’t Say or Uncertain is included. The assumption is that the person both can and will provide an accurate self-report. These tests include items dealing with specific behaviors, attitudes, interests, and values. We will discuss the MMPI, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (Hathaway & McKinley, 1943), revised to become the MMPI-2 in 1989 (Butcher, Dahlstrom, Graham, Tellegen, & Kaemmer, 1989). It is the most used personality test in the world (Weiner & Greene, 2008), and it has been translated into more than 100 languages.

The MMPI-2 uses a True–False–Cannot Say format with 567 simple statements (such as “I like to cook”) and takes about 60 to 90 minutes to complete. Most of the statements are from the original MMPI. Some were reworded to update the item content and to eliminate sexist language, and most of the questions pertaining to religion and sexual practices were eliminated (Ben-Porath & Butcher, 1989). The MMPI was developed to be a measure of abnormal personality, with 10 clinical scales. Many of the test statements have obvious connections to disorders, such as “I believe I am being plotted against,” but many are just simple ordinary statements, such as “I am neither gaining nor losing weight.”

The MMPI test statements were chosen in the same way that Binet and Simon chose test items for their first valid test of intelligence (discussed in Chapter 6). Binet and Simon developed a large pool of possible test items and then chose only those items that differentiated fast and slow learners. Similarly, a large pool of possible test items (simple statements of all types) was developed, and then only those items that were answered differently (by a representative sample of people suffering from a specific disorder versus a group of normal people) were chosen for the test. It didn’t matter what each group responded or what the content of the statement happened to be; what mattered was that the two groups generally responded to the item in opposite ways. Thus, the test developers were only concerned with whether, and not why, the items were answered differently by the groups. This test construction method allowed the test developers to choose items that clearly identified the response patterns of people with 10 different disorders (for example, depression or schizophrenia).

The MMPI and MMPI-2 are scored by a computer, which then generates a profile of the test taker on 10 clinical (disorder) scales. There are also test statements that comprise the basis for three validity scales, which attempt to detect test takers who are trying to cover up problems and fake profiles or who were careless in their responding. For example, there is a lie detection scale that assesses the extent to which the test taker is lying to create a particular test profile. The lie scale is based on responses to a set of test items such as “I get angry sometimes,” to which most people would respond “True.” The profile for a person consistently answering “False” to these questions would be invalidated.

Personality inventories like the MMPI are objective tests and are objectively scored by a computer. The computer converts the test taker’s responses into a personality profile for the trait or disorder dimensions that the test is measuring. This is why the MMPI has been so popular in clinical settings for making diagnoses of personality problems. Its test construction method leads to good predictive validity for its clinical scales, and its objective scoring procedure leads to reliability in interpretation. Projective personality tests, which we will discuss next, do not have good validity or reliability, but are widely used.

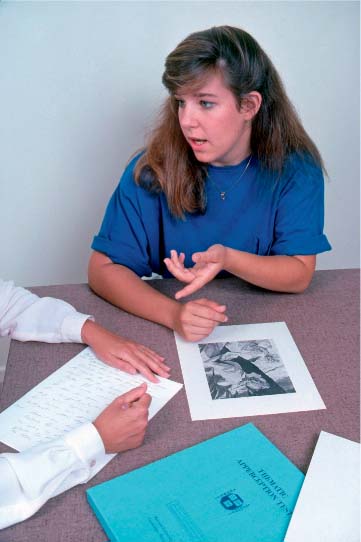

Projective tests. The chances are that when personality tests are mentioned, you think of the Rorschach Inkblot Test, a projective personality test. In contrast with personality inventories, a projective test is a series of ambiguous stimuli, such as inkblots, to which the test taker must respond about his perceptions of the stimuli. An objective response format is not used. Test takers are asked to describe the stimulus or tell a story about it. We will discuss the two most used projective tests, the Rorschach Inkblot Test and the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT).

Projective tests aren’t administered, scored, or interpreted in the same way as the MMPI, MMPI-2, and other objective personality inventories. They are not as objective, especially with respect to interpretation. The most popular and widely used projective test is the Rorschach Inkblot Test (often referred to as The Rorschach), which Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach included as part of a monograph in 1921 (Rorschach, 1921/1942). Actually Rorschach never intended this to be a test of personality. He created it for use as a diagnostic tool for schizophrenia. Sadly, in 1922, the year after his monograph was published, he died from appendicitis; he was only 37 years old. There are only 10 symmetric inkblots used in the test. Five are in black ink, two in black and red ink, and three are multicolored. All have a white background. The test taker is asked what he sees in each inkblot, though the inkblots are ambiguous and have no inherent meaning. The examiner then goes through the cards and asks the test taker to clarify his responses by identifying the various parts of the inkblot that led to the response.

The assumption is that the test taker’s responses are projections of his personal conflicts and personality dynamics. This means that the test taker’s responses have to be interpreted, which makes the test scoring subjective and creates great variability among test scorers. In fact, one could view the test scorer’s interpretations as projections themselves. The Rorschach Inkblot Test has been widely used (Watkins, Campbell, Nieberding, & Hallmark, 1995), but it has yet to be demonstrated that this test is either reliable or valid (Dawes, 1994; Lilienfeld, Wood, & Garb, 2000), leading some researchers to call for a moratorium on its use (Garb, 1999). If you are interested in the Rorschach Inkblot Test, all 10 of the inkblots along with popular responses to each are given in the Rorschach Inkblot Test entry at the Wikipedia Web site, www.wikipedia.org.

Now let’s consider another popular projective test, the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), developed by Henry Murray and his colleagues in the 1930s (Morgan & Murray, 1935). The TAT consists of 31 cards (the original version had only 20), 30 with black and white pictures of ambiguous settings and one blank card (the ultimate in ambiguity). Only 10 or so of the 31 cards are used in an individual testing session. The test taker is told that this is a story-telling test and that for each picture he has to make up a story. He is to tell what has happened before, what is happening now, what the people are feeling and thinking, and how things will turn out. In scoring these responses, the scorer looks for recurring themes in the feelings, relationships, and motives of the characters in the created stories. Like the Rorschach Inkblot Test, however, it has yet to be demonstrated that the TAT scoring (interpretation) is either reliable or valid (Lilienfeld, Wood, & Garb, 2000). You are probably wondering why these two projective tests are so popular if neither has demonstrated reliability or validity. Therapists who use them believe that such tests allow them to explore aspects of the test taker’s personality that the reliable and valid objective personality tests do not. These therapists tend to be psychoanalysts who believe projections are meaningful; therefore, the tests’ subjective nature is not problematic for them.

Section Summary

The trait approach to personality attempts to identify the basic traits (dimensions) we need to describe human personality. These traits are the building blocks of personality. Given the basic traits, each person’s personality can be viewed as her unique combination of values on these basic personality dimensions. Using factor analysis and other statistical techniques, trait theorists have proposed theories with varying numbers of basic dimensions. For example, Hans Eysenck has proposed three dimensions—psychoticism, extraversion, and neuroticism. Recent trait research indicates that five factors (the Big Five—openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) are necessary. These five factors seem to be stable throughout adulthood and universal across gender and many diverse languages and cultures.

To assess personality, psychologists make use of two types of tests—personality inventories and projective tests. A personality inventory is a set of questions or statements for which the test taker must indicate whether they apply to her or not. Such objective tests usually employ a True–False–Cannot Say format. The most used personality inventory is the MMPI/MMPI-2. These tests have predictive validity for diagnosing personality problems on 10 clinical scales, since the items on these tests were chosen because they differentiated normal people from people diagnosed with the 10 disorders. Projective tests are more subjective tests in which the test taker must respond about her perceptions of a series of ambiguous stimuli. The assumption is that the test taker’s responses are projections of her personal conflicts and personality dynamics. Though widely used, projective tests, such as the Rorschach Inkblot Test and the TAT, have yet to be shown to be reliable or valid.

Concept Check | 3

Explain why factor analysis can lead to different numbers of basic personality dimensions.

Explain why factor analysis can lead to different numbers of basic personality dimensions.There are two major reasons that factor analysis can lead to different numbers of basic personality dimensions. The first concerns the level of abstraction at which a theorist uses the analysis. Some theorists have used a level of analysis in which some of the dimensions are still correlated (Cattell); others (Eysenck) have used higher-order factors that are not correlated. Thus, theorists may use different levels of inclusiveness, with those using more global levels leading to fewer factors. Second, and independent of level of abstraction, is what data are being analyzed. Different theorists have examined different databases. Obviously, varying input will lead to varying results, even with the same type of analysis.

Explain how the test construction method used to develop the MMPI ensures predictive validity for the test.

Explain how the test construction method used to develop the MMPI ensures predictive validity for the test.The test construction method used to develop the MMPI involves only choosing test items that clearly differentiate the responding of two distinct groups. In the case of the MMPI, test items were chosen that were responded to differently by representative samples of people with 1 of 10 different disorders versus normal people. Thus, predictive validity is ensured because only test items that definitely differentiate test takers according to the purpose of the test are chosen. In the case of the MMPI, this means that various clinical personality problems, such as depression or schizophrenia, can be detected by comparing a test taker’s response pattern to those of the disordered groups.