Page 371

social psychology The scientific study of how we influence one another’s behavior and thinking.

Humans are social animals. We affect one another’s thoughts and actions, and how we do so is the topic of this chapter. This research area is called social psychology—the scientific study of how we influence one another’s behavior and thinking. To understand what is meant by such social influence, we’ll consider two real-world incidents in which social forces influenced behavior, and then, later in the chapter, we’ll return to each incident to see how social psychologists explain them.

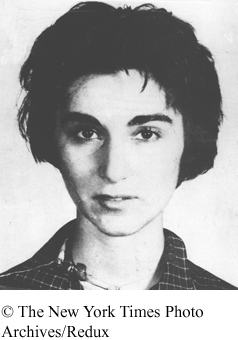

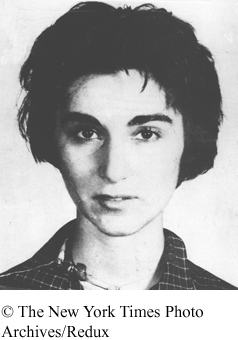

Kitty Genovese

© The New York Times Photo Archives/Redux

The first incident is the brutal rape and murder of Kitty Genovese in New York City in 1964 (briefly discussed in Chapter 1). Kitty Genovese was returning home from work late one night, when she was attacked in front of her apartment building. The attack was a prolonged one over a half-hour period in which the attacker left and came back. Kitty screamed for help and struggled with the knife-wielding attacker, but no help was forthcoming. Some apartment residents saw the attack, and others heard her screams and pleas for help. Exactly how many residents witnessed the attack is not clear. A recent analysis by Manning, Levine, and Collins (2007) of the court transcripts of the murder trial, an examination of other legal documents associated with the case, and a review of research carried out by a local historian and lawyer familiar with the case revealed a much different account of what happened than was depicted in the New York Times story that was described in Chapter 1. Their analysis indicated that the number of witnesses who actually saw the attack was considerably less than 38 (probably only a half dozen or so at most); that possibly a few more witnesses heard something; that none of the witnesses actually saw the stabbing; that the first attack was very brief because the attacker was temporarily scared away by the shouting of at least one of the witnesses; that the second, more prolonged, fatal attack occurred out of view and earshot of all but one witness, who chose not to intervene; that at least one person actually called the police after the first attack but the police did not respond to the call; and that a 70-year-old female neighbor of Kitty’s actually left her apartment and went to the crime scene without knowing whether or not the murderer had fled (Lemann, 2014; Manning et al., 2007). With respect to the first call to the police, there was no 911 system in 1964, and calls from this area were not always welcomed by the police because of a bar there that had a reputation for trouble. In sum, Manning et al. showed that all of the key features of the New York Times report of the murder were inaccurate. Regardless, Kitty’s cries for help went unanswered until it was too late. Someone finally called the police after the attacker had left, and they responded this time, but Kitty died soon thereafter on her way to the hospital. It is important to realize that social psychology researchers in 1964 did not know that the New York Times version of the attack was rife with errors. Thus, they conducted research to try to explain why 38 witnesses watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in a prolonged attack that lasted over 30 minutes and not one witness telephoned the police or intervened until it was too late. Media accounts blamed apathy created by a big-city culture for the many bystanders’ failure to help (Rosenthal, 1964). Based on their experiments, social psychology researchers, however, provided a very different explanation of the bystanders’ behavior. We will describe this explanation in the section on social influence, when we discuss bystander intervention. Incidentally, Winston Moseley, the man who killed Kitty Genovese, died in prison in 2016. He was 81 and had been incarcerated for the past 52 years.

Page 372

The second incident occurred in 1978, when over 900 people who were members of Reverend Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple religious cult in Jonestown, Guyana (South America), committed mass suicide by drinking cyanide-laced Kool-Aid (though some sources say it was Flavor-Aid, a drink mix similar to Kool-Aid). These were Americans who had moved with Jones from San Francisco to Jonestown in 1977. Jonestown parents not only drank the poisoned Kool-Aid, but they also gave it to their infant children to drink. Strangely, the mass suicide occurred in a fairly orderly fashion as one person after another drank the poison. Hundreds of people went into convulsions and died within minutes. What social forces made so few of these people willing to disobey Reverend Jones’s command for this unified act of mass suicide? We will return to this question in the social influence section, when we discuss obedience.

What if you had been one of those people who witnessed Kitty Genovese’s murder? Would you have intervened or called the police? If you are like most people, you probably think that you would have done so. Similarly, most people would probably say that they would not have drunk the poison at Jonestown. However, the vast majority did so. Why is there at times this discrepancy between what we say we would do and what we actually do? Social psychologists would say that when we just think about what our behavior would be in such a situation, we are not subject to the social forces that are operating in the actual situation. If you’re in the situation, however, social forces are operating and may guide your behavior in a different way. In summary, situational social forces greatly influence our behavior and thinking. Keep this in mind as we discuss various types of social influence and social thinking.