Reading sources critically

As you begin reading the sources you have chosen, keep an open mind. Do not let your personal beliefs prevent you from listening to new ideas and opposing viewpoints. Be curious about the wide range of positions in the research conversation you are entering. Your research question should guide you as you engage your sources.

When you read critically, you are examining an author’s assumptions, assessing evidence, and weighing conclusions.

Reading critically means

- reading carefully (What does the source say?)

- reading skeptically (Are any of the author’s points or conclusions problematic?)

- reading evaluatively (How does this source help me make my argument?)

To see one student’s critical reading of a source text, see A1.

using sources responsibly: Take time to read the entire source and to understand an author’s arguments, assumptions, and conclusions. Try to avoid taking quotations from the first few pages of a source before you understand if the words and ideas are representative of the work as a whole.

Distinguishing between primary and secondary sources

As you begin assessing evidence in a source, determine whether you are reading a primary or a secondary source. Primary sources include original documents such as letters, diaries, films, legislative bills, laboratory studies, field research reports, and eyewitness accounts. Secondary sources are commentaries on primary sources—another writer’s opinions about or interpretation of a primary source.

Although a primary source is not necessarily more reliable than a secondary source, it has the advantage of being a firsthand account. You can better evaluate what a secondary source says if you have first read any primary sources it discusses.

Being alert for signs of bias

Bias is a way of thinking, a tendency to be partial, that prevents people and publications from viewing a topic objectively. Both in print and online, some sources are more objective than others. If you are exploring the rights of organizations like WikiLeaks to distribute sensitive government documents over the Internet, for example, you may not find objective, unbiased information in a US State Department report. If you are researching timber harvesting practices, you are likely to encounter bias in publications sponsored by environmental groups. As a researcher, you will need to consider any suspected bias as you assess the source. If you are uncertain about a source’s special interests, seek the help of a reference librarian.

Like publishers, some authors are more objective than others. If you have reason to believe that a writer is particularly biased, you will want to assess his or her arguments with special care. For a list of questions worth asking, see the chart above.

Assessing the author’s argument

In nearly all subjects worth writing about, there is some element of argument, so expect to encounter debates and disagreements among authors. In fact, areas of disagreement give you entry points in a research conversation. The questions in the chart in A3-c can help you weigh the strengths and weaknesses of each author’s argument.

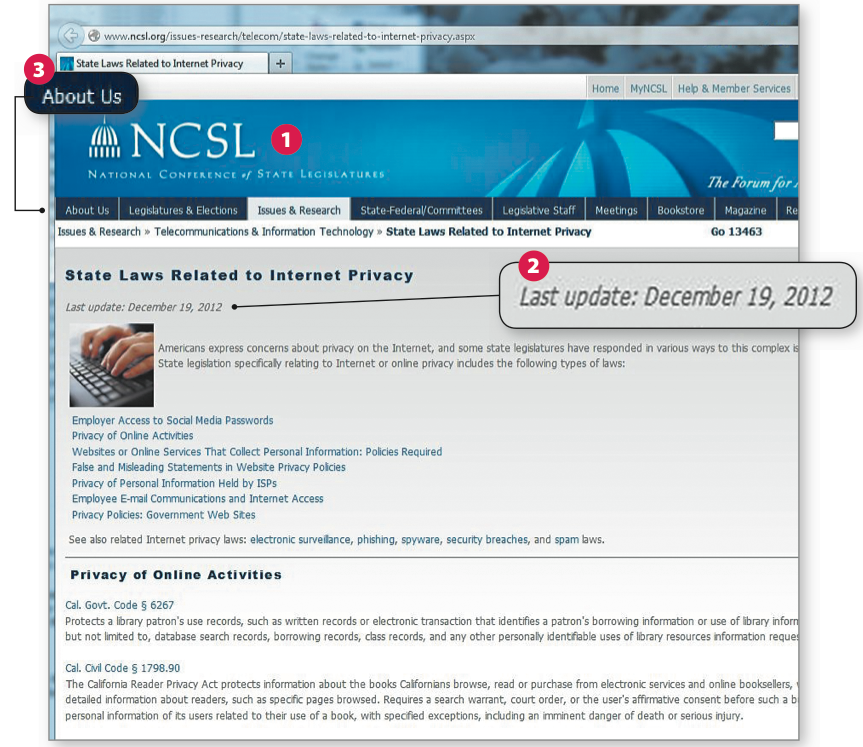

evaluating a web site: checking reliability

Source: Copyright © 2014 National Conference of State Legislatures.

1 This page on Internet monitoring and workplace privacy appears on a Web site sponsored by the National Conference of State Legislatures. The NCSL is a bipartisan group that functions as a clearinghouse of ideas and research of interest to state lawmakers. It is also a lobby for state issues before the US government. The URL ending .org marks this sponsor as a nonprofit organization.

2 A clear date of publication shows currency.

3 An “About Us” page confirms that this is a credible organization whose credentials can be verified.

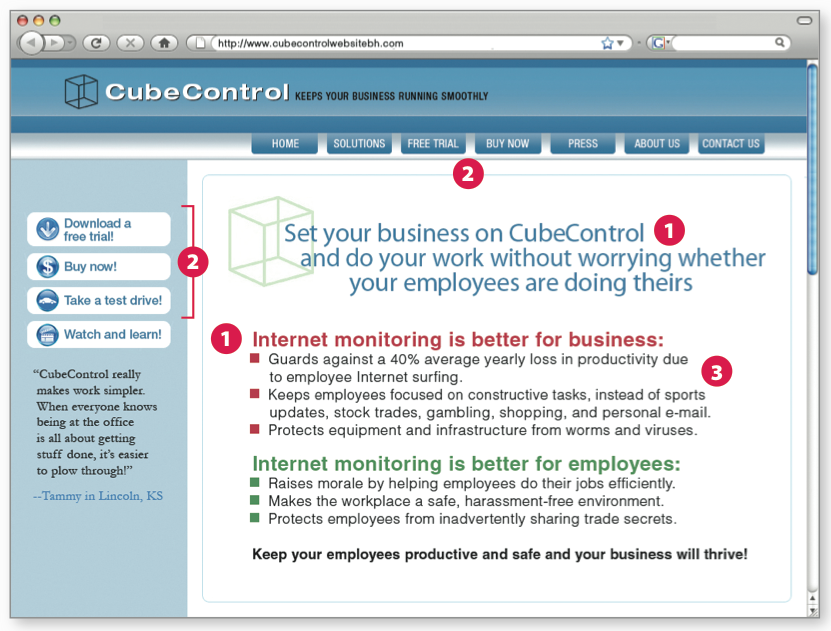

evaluating a web site: checking purpose

1 The site is sponsored by a company that specializes in employee-monitoring software.

2 Repeated links for trial downloads and purchase suggest the site’s intended audience: consumers seeking to purchase software (probably not researchers seeking detailed information about employees’ use of the Internet in the workplace).

3 The site appears to provide information and even shows statistics from studies, but ultimately the purpose of the site is to sell a product.

Evaluating all sources

Checking for signs of bias

- Does the author or publisher endorse political or religious views that could affect objectivity?

- Is the author or publisher associated with a special-interest group, such as PETA or the National Rifle Association, that might present only one side of an issue?

- Are alternative views presented and addressed? How fairly does the author treat opposing views? (See A3-c.)

- Does the author’s language show signs of bias?

Assessing an argument

- What is the author’s central claim or thesis?

- How does the author support this claim—with relevant and sufficient evidence or with just a few anecdotes or emotional examples?

- Are statistics consistent with those you encounter in other sources? Have they been used fairly? Does the author explain where the statistics come from?

- Are any of the author’s assumptions questionable?

- Does the author consider opposing arguments and refute them persuasively? (See A4-f.)

- Does the author fall prey to any logical fallacies? (See A3-a.)

Evaluating sources you find on the Web

Authorship

- Does the Web site or document have an author? You may need to do some hunting to find the author’s name. If you have landed directly on an internal page of a site, for example, you may need to navigate to the home page or find an “about this site” link to learn the name of the author.

- If there is an author, can you tell whether he or she is knowledgeable and credible? When the author’s qualifications aren’t listed on the site itself, look for links to the author’s home page, which may provide evidence of his or her expertise.

Sponsorship

- Who, if anyone, sponsors the site? The sponsor of a site is often named and described on the home page.

- What does the URL tell you? The URL ending often indicates the type of group hosting the site: commercial (.com), educational (.edu), nonprofit (.org), governmental (.gov), military (.mil), or network (.net). URLs may also indicate a country of origin: .uk (United Kingdom) or .jp (Japan), for instance.

Purpose and audience

- Why was the site created: To argue a position? To sell a product? To inform readers?

- Who is the site’s intended audience?

Currency

- How current is the site? Check for the date of publication or the latest update, often located at the bottom of the home page or at the beginning or end of an internal page.

- How current are the site’s links? If many of the links no longer work, the site may be too dated for your purposes.