America’s History: Printed Page 321

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 293

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 285

“The Democracy” and the Election of 1828

Martin Van Buren and the politicians handling Andrew Jackson’s campaign for the presidency had no reservations about running for office. To put Jackson in the White House, Van Buren revived the political coalition created by Thomas Jefferson, championing policies that appealed to both southern planters and northern farmers and artisans, the “plain Republicans of the North.” John C. Calhoun, Jackson’s running mate, brought his South Carolina allies into Van Buren’s party, and Jackson’s close friends in Tennessee rallied voters throughout the Old Southwest. The Little Magician hoped that a national party would reconcile the diverse “interests” that, as James Madison suggested in “Federalist No. 10”, inevitably existed in a large republic. Equally important, added Jackson’s ally Duff Green, it would put the “anti-slave party in the North … to sleep for twenty years to come.”

At Van Buren’s direction, the Jacksonians orchestrated a massive publicity campaign. In New York, fifty Democrat-funded newspapers declared their support for Jackson. Elsewhere, Jacksonians used mass meetings, torchlight parades, and barbecues to celebrate the candidate’s frontier origin and rise to fame. They praised “Old Hickory” as a “natural” aristocrat, a self-made man.

The Jacksonians called themselves Democrats or “the Democracy” to convey their egalitarian message. As Thomas Morris told the Ohio legislature, Democrats were fighting for equality: the republic had been corrupted by legislative charters that gave “a few individuals rights and privileges not enjoyed by the citizens at large.” Morris promised that the Democracy would destroy such “artificial distinction.” Jackson himself declared that “equality among the people in the rights conferred by government” was the “great radical principle of freedom.”

Jackson’s message appealed to many social groups. His hostility to corporations and to Clay’s American System won support from northeastern artisans and workers who felt threatened by industrialization. Jackson also captured the votes of Pennsylvania ironworkers and New York farmers who had benefitted from the controversial Tariff of Abominations. Yet, by astutely declaring his support for a “judicious” tariff that would balance regional interests, Jackson remained popular in the South. Old Hickory likewise garnered votes in the Southeast and Midwest, where his well-known hostility toward Native Americans reassured white farmers seeking Indian removal.

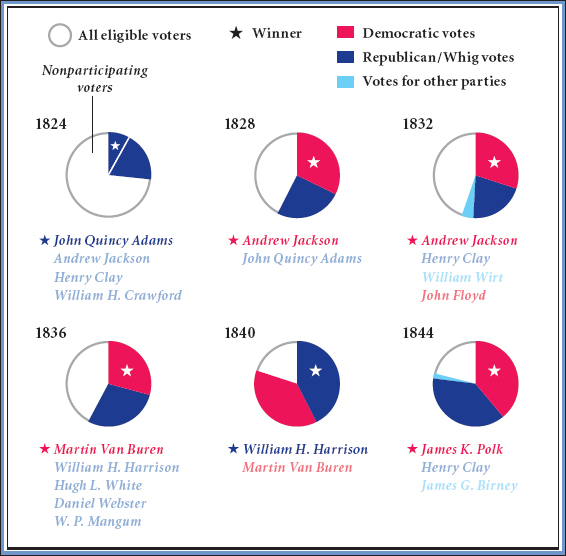

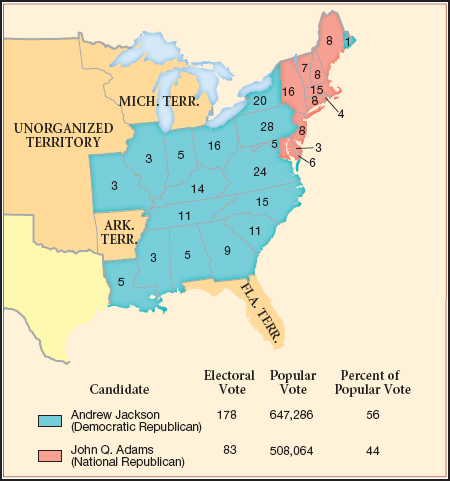

The Democrats’ celebration of popular rule carried Jackson into office. In 1824, about one-quarter of the electorate had voted; in 1828, more than one-half went to the polls, and 56 percent voted for the Tennessee senator (Figure 10.1 and Map 10.2). The first president from a trans-Appalachian state, Jackson cut a dignified figure as he traveled to Washington. He “wore his hair carelessly but not ungracefully arranged,” an English observer noted, “and in spite of his harsh, gaunt features looked like a gentleman and a soldier.” Still, Jackson’s popularity and sharp temper frightened men of wealth. Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, a former Federalist and now a corporate lawyer, warned his clients that the new president would “bring a breeze with him. Which way it will blow, I cannot tell [but] … my fear is stronger than my hope.” Supreme Court justice Joseph Story shared Webster’s apprehensions. Watching an unruly Inauguration Day crowd climb over the elegant White House furniture to congratulate Jackson, Story lamented that “the reign of King ‘Mob’ seemed triumphant.”

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

Jackson lost the presidential election of 1824 and won in 1828: what changes explain these different outcomes?