America’s History: Printed Page 323

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 296

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 287

The Tariff and Nullification

The Tariff of 1828 had helped Jackson win the presidency, but it saddled him with a major political crisis. There was fierce opposition to high tariffs throughout the South and especially in South Carolina. That state was the only one with an African American majority — 56 percent of the population in 1830 — and its slave owners, like the white sugar planters in the West Indies, feared a black rebellion. Even more, they worried about the legal abolition of slavery. The British Parliament had declared that slavery in its West Indian colonies would end in 1833; South Carolina planters, vividly recalling northern efforts to end slavery in Missouri (Chapter 8), worried that the U.S. Congress would follow the British lead. So they attacked the tariff, both to lower rates and to discourage the use of federal power to attack slavery.

The crisis began in 1832, when high-tariff congressmen ignored southern warnings that they were “endangering the Union” and reenacted the Tariff of Abominations. In response, leading South Carolinians called a state convention, which in November boldly adopted an Ordinance of Nullification declaring the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 to be null and void. The ordinance prohibited the collection of those duties in South Carolina after February 1, 1833, and threatened secession if federal officials tried to collect them.

South Carolina’s act of nullification — the argument that a state has the right to void, within its borders, a law passed by Congress — rested on the constitutional arguments developed in The South Carolina Exposition and Protest (1828). Written anonymously by Vice President John C. Calhoun, the Exposition gave a localist (or sectional) interpretation to the federal union. Because each state or geographic region had distinct interests, localists argued, protective tariffs and other national legislation that operated unequally on the various states lacked fairness and legitimacy — in fact, they were unconstitutional. An obsessive defender of the interests of southern slave owners, Calhoun exaggerated the frequency and severity of such legislation, declaring, “Constitutional government and the government of a majority are utterly incompatible.”

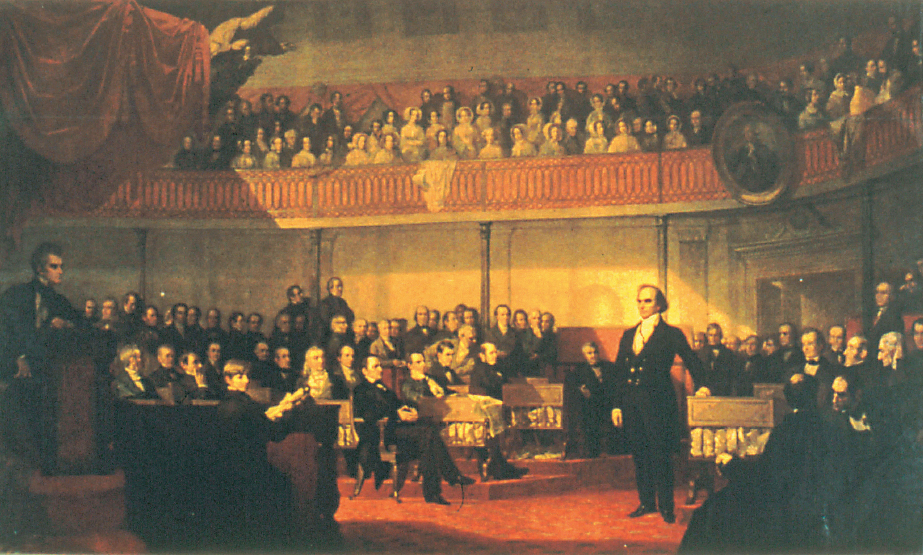

Calhoun’s constitutional doctrines reflected the arguments advanced by Jefferson and Madison in the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798. Those resolutions asserted that, because state-based conventions had ratified the Constitution, sovereignty lay in the states, not in the people. Beginning from this premise, Calhoun argued that a state convention could declare a congressional law to be void within the state’s borders. Replying to this states’ rights interpretation of the Constitution, which had little support in the text of the document, Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts presented a nationalist interpretation that celebrated popular sovereignty and Congress’s responsibility to secure the “general welfare.”

Jackson hoped to find a middle path between Webster’s strident nationalism and Calhoun’s radical doctrine of localist federalism. The Constitution clearly gave the federal government the authority to establish tariffs, and Jackson vowed to enforce it. He declared that South Carolina’s Ordinance of Nullification violated the letter of the Constitution and was “destructive of the great object for which it was formed.” More pointedly, he warned, “Disunion by armed force is treason.” At Jackson’s request, Congress in early 1833 passed a military Force Bill, authorizing the president to compel South Carolina’s obedience to national laws. Simultaneously, Jackson addressed the South’s objections to high import duties with a new tariff act that, over the course of a decade, reduced rates to the modest levels of 1816. Subsequently, export-hungry midwestern wheat farmers joined southern planters in advocating low duties to avoid retaliatory tariffs by foreign nations. “Illinois wants a market for her agricultural products,” declared Senator Sidney Breese in 1846. “[S]he wants the market of the world.”

Having won the political battle by securing a tariff reduction, the South Carolina convention did not press its constitutional stance on nullification. Jackson was satisfied. He had assisted the South economically while upholding the constitutional principle of national authority — a principle that Abraham Lincoln would embrace to defend the Union during the secession crisis of 1861.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

How did South Carolina justify nullification on constitutional grounds?