America’s History: Printed Page 326

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 300

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 291

Indian Removal

The status of Native American peoples posed an equally complex political problem. By the late 1820s, white voices throughout the South and Midwest demanded the resettlement of Indian peoples west of the Mississippi River. Many whites who were sympathetic to Native Americans also favored resettlement. Removal to the West seemed the only way to protect Indians from alcoholism, financial exploitation, and cultural decline.

However, most Indians did not want to leave their ancestral lands. For centuries, Cherokees and Creeks had lived in Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama; Chickasaws and Choctaws in Mississippi and Alabama; and Seminoles in Florida. During the War of 1812, Andrew Jackson had forced the Creeks to relinquish millions of acres, but Indian tribes still controlled vast tracts and wanted to keep them.

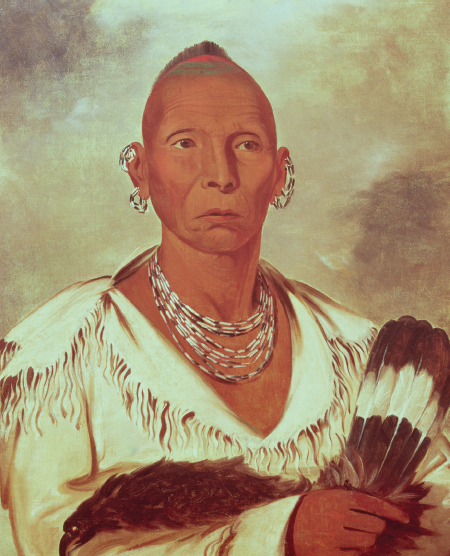

Cherokee Resistance But on what terms? Some Indians had adopted white ways. An 1825 census revealed that various Cherokees owned 33 gristmills, 13 sawmills, 2,400 spinning wheels, 760 looms, and 2,900 plows. Many of these owners were mixed-race, the offspring of white traders and Indian women. They had grown up in a bicultural world, knew the political and economic ways of whites, and often favored assimilation into white society. Indeed, some of these mixed-race people were indistinguishable from southern planters. At his death in 1809, Georgia Cherokee James Vann owned one hundred black slaves, two trading posts, and a gristmill. Three decades later, forty other mixed-blood Cherokee families each owned ten or more African American workers.

Prominent mixed-race Cherokees believed that integration into American life was the best way to protect their property and the lands of their people. In 1821, Sequoyah, a part-Cherokee silversmith, perfected a system of writing for the Cherokee language; six years later, mixed-race Cherokees devised a new charter of Cherokee government modeled directly on the U.S. Constitution. “You asked us to throw off the hunter and warrior state,” Cherokee John Ridge told a Philadelphia audience in 1832. “We did so. You asked us to form a republican government: We did so. … You asked us to learn to read: We did so. You asked us to cast away our idols, and worship your God: We did so.” Full-blood Cherokees, who made up 90 percent of the population, resisted many of these cultural and political innovations but were equally determined to retain their ancestral lands. “We would not receive money for land in which our fathers and friends are buried,” one full-blood chief declared. “We love our land; it is our mother.”

What the Cherokees did or wanted carried no weight with the Georgia legislature. In 1802, Georgia had given up its western land claims in return for a federal promise to extinguish Indian landholdings in the state. Now it demanded fulfillment of that pledge. Having spent his military career fighting Indians and seizing their lands, Andrew Jackson gave full support to Georgia. On assuming the presidency, he withdrew the federal troops that had protected Indian enclaves there and in Alabama and Mississippi. The states, he declared, were sovereign within their borders.

The Removal Act and Its Aftermath Jackson then pushed the Indian Removal Act of 1830 through Congress over the determined opposition of evangelical Protestant men — and women. To block removal, Catharine Beecher and Lydia Sigourney composed a Ladies Circular, which urged “benevolent ladies” to use “prayers and exertions to avert the calamity of removal.” Women from across the nation flooded Congress with petitions. Nonetheless, Jackson’s bill squeaked through the House of Representatives by a vote of 102 to 97.

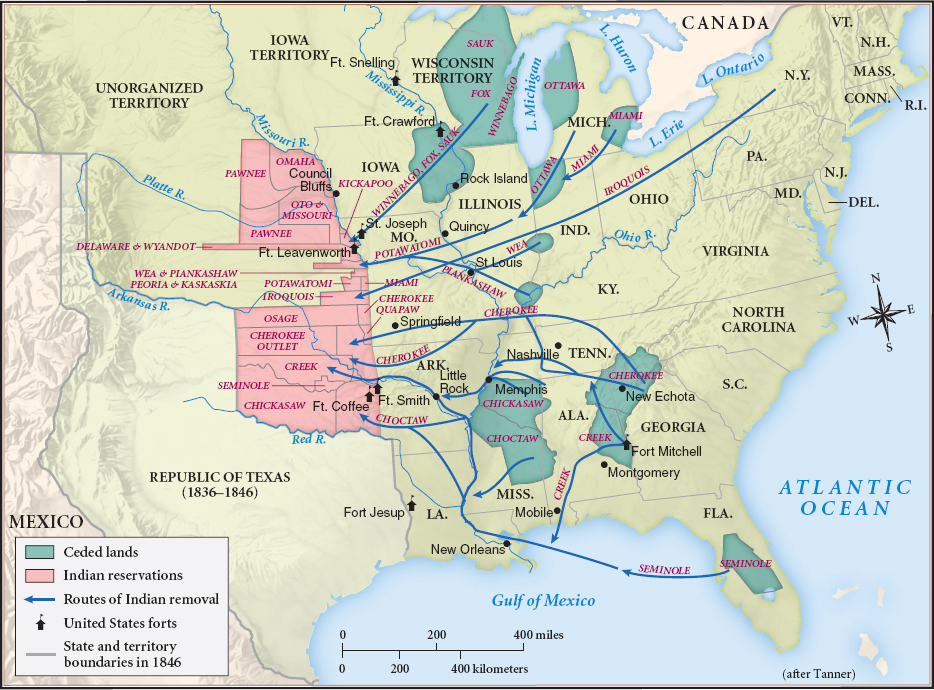

The Removal Act created the Indian Territory on national lands acquired in the Louisiana Purchase and located in present-day Oklahoma and Kansas. It promised money and reserved land to Native American peoples who would give up their ancestral holdings east of the Mississippi River. Government officials promised the Indians that they could live on their new land, “they and all their children, as long as grass grows and water runs.” However, as one Indian leader noted, on the Great Plains “water and timber are scarcely to be seen.” When Chief Black Hawk and his Sauk and Fox followers refused to leave rich, well-watered farmland in western Illinois in 1832, Jackson sent troops to expel them by force. Eventually, the U.S. Army pursued Black Hawk into the Wisconsin Territory and, in the brutal eight-hour Bad Axe Massacre, killed 850 of his 1,000 warriors. Over the next five years, American diplomatic pressure and military power forced seventy Indian peoples to sign treaties and move west of the Mississippi (Map 10.3).

In the meantime, the Cherokees had carried the defense of their lands to the Supreme Court, where they claimed the status of a “foreign nation.” In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), Chief Justice John Marshall denied that claim and declared that Indian peoples were “domestic dependent nations.” However, in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Marshall and the Court sided with the Cherokees against Georgia. Voiding Georgia’s extension of state law over the Cherokees, the Court held that Indian nations were “distinct political communities, having territorial boundaries, within which their authority is exclusive [and is] guaranteed by the United States.”

Instead of guaranteeing the Cherokees’ territory, the U.S. government took it from them. In 1835, American officials and a minority Cherokee faction negotiated the Treaty of New Echota, which specified that Cherokees would resettle in Indian Territory. When only 2,000 of 17,000 Cherokees had moved by the May 1838 deadline, President Martin Van Buren ordered General Winfield Scott to enforce the treaty. Scott’s army rounded up 14,000 Cherokees (including mixed-race African Cherokees) and marched them 1,200 miles, an arduous journey that became known as the Trail of Tears. Along the way, 3,000 Indians died of starvation and exposure. Once in Oklahoma, the Cherokees excluded anyone of “negro or mulatto parentage” from governmental office, thereby affirming that full citizenship in their nation was racially defined. Just as the United States was a “white man’s country,” so Indian Territory would be defined as a “red man’s country.”

Encouraged by generous gifts of land, the Creeks, Chickasaws, and Choctaws moved west of the Mississippi, leaving the Seminoles in Florida as the only numerically significant Indian people remaining in the Southeast. Government pressure persuaded about half of the Seminoles to migrate to Indian Territory, but families whose ancestors had intermarried with runaway slaves feared the emphasis on “blood purity” there. During the 1840s, they fought a successful guerrilla war against the U.S. Army and retained their lands in central Florida. These Seminoles were the exception: the Jacksonians had forced the removal of most eastern Indian peoples.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How did the views of Jackson and John Marshall differ regarding the status and rights of Indian peoples?