America’s History: Printed Page 318

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 290

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 282

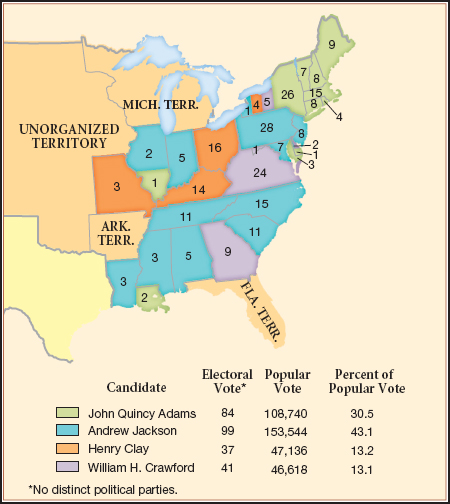

The Election of 1824

The advance of political democracy in the states undermined the traditional notable-dominated system of national politics. After the War of 1812, the aristocratic Federalist Party virtually disappeared, and the Republican Party splintered into competing factions. As the election of 1824 approached, five Republican candidates campaigned for the presidency. Three were veterans of President James Monroe’s cabinet: Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, the son of former president John Adams; Secretary of War John C. Calhoun; and Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford. The other candidates were Henry Clay of Kentucky, the hard-drinking, dynamic Speaker of the House of Representatives; and General Andrew Jackson, now a senator from Tennessee. When the Republican caucus in Congress selected Crawford as the party’s official nominee, the other candidates took their case to the voters. Thanks to democratic reforms, eighteen of the twenty-four states required popular elections (rather than a vote of the state legislature) to choose their representatives to the electoral college.

Each candidate had strengths. Thanks to his diplomatic successes as secretary of state, John Quincy Adams enjoyed national recognition; and his family’s prestige in Massachusetts ensured him the electoral votes of New England. Henry Clay based his candidacy on the American System, his integrated mercantilist program of national economic development similar to the Commonwealth System of the state governments. Clay wanted to strengthen the Second Bank of the United States, raise tariffs, and use tariff revenues to finance internal improvements, that is, public works such as roads and canals. His nationalistic program won praise in the West, which needed better transportation, but elicited sharp criticism in the South, which relied on rivers to market its cotton and had few manufacturing industries to protect. William Crawford of Georgia, an ideological heir of Thomas Jefferson, denounced Clay’s American System as a scheme to “consolidate” political power in Washington. Recognizing Crawford’s appeal in the South, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina withdrew from the race and endorsed Andrew Jackson.

As the hero of the Battle of New Orleans, Jackson benefitted from the surge of patriotism after the War of 1812. Born in the Carolina backcountry, Jackson settled in Nashville, Tennessee, where he formed ties to influential families through marriage and a career as an attorney and a slave-owning cotton planter. His rise from common origins symbolized the new democratic age, and his reputation as a “plain solid republican” attracted voters in all regions. Still, Jackson’s strong showing in the electoral college surprised most political leaders. The Tennessee senator received 99 electoral votes; Adams garnered 84 votes; Crawford, struck down by a stroke during the campaign, won 41; and Clay finished with 37 (Map 10.1).

Because no candidate received an absolute majority, the Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution (ratified in 1804) set the rules: the House of Representatives would choose the president from among the three highest vote-getters. This procedure hurt Jackson because many congressmen feared that the rough-hewn “military chieftain” might become a tyrant. Excluded from the race, Henry Clay used his influence as Speaker to thwart Jackson’s election. Clay assembled a coalition of representatives from New England and the Ohio River Valley that voted Adams into the presidency in 1825. Adams showed his gratitude by appointing Clay his secretary of state, the traditional stepping-stone to the presidency. Clay’s appointment was politically fatal for both men: Jackson’s supporters accused Clay and Adams of making a corrupt bargain, and they vowed to oppose Adams’s policies and to prevent Clay’s rise to the presidency.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

Why did Jacksonians consider the political deal between Adams and Clay “corrupt”?