America’s History: Printed Page 358

THINKING LIKE A HISTORIAN |  |

Dance and Social Identity in Antebellum America

Styles of dance and attitudes toward them tell us a great deal about cultural and social norms. When nineteenth-century Americans took to partying, their dances — regardless of the class or ethnic identity of the dancers — focused more on individual couples and allowed more room for improvisation and intimacy than the dance forms of the previous century.

William Sidney Mount, Rustic Dance After a Sleigh Ride, 1830. In the eighteenth century, wealthy, fashionable Americans danced the French minuet, a ceremonious and graceful dance in which couples executed prescribed steps while barely touching. Ordinary white folks preferred the country dances brought by their ancestors from Europe, which also involved intricate steps, line formations, and limited physical contact. Mount (1807–1868) was self-taught, lived in rural Long Island, and depicted scenes of everyday life. This painting, replete with amorous pursuits, depicts a traditional contra dance in which the lead couple advances a few steps and then sashays to the back of the line, as another couple takes its place.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts, USA/Bequest of Martha C. Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik/Collection of American Paintings, 1815–65/The Bridgeman Art Library.

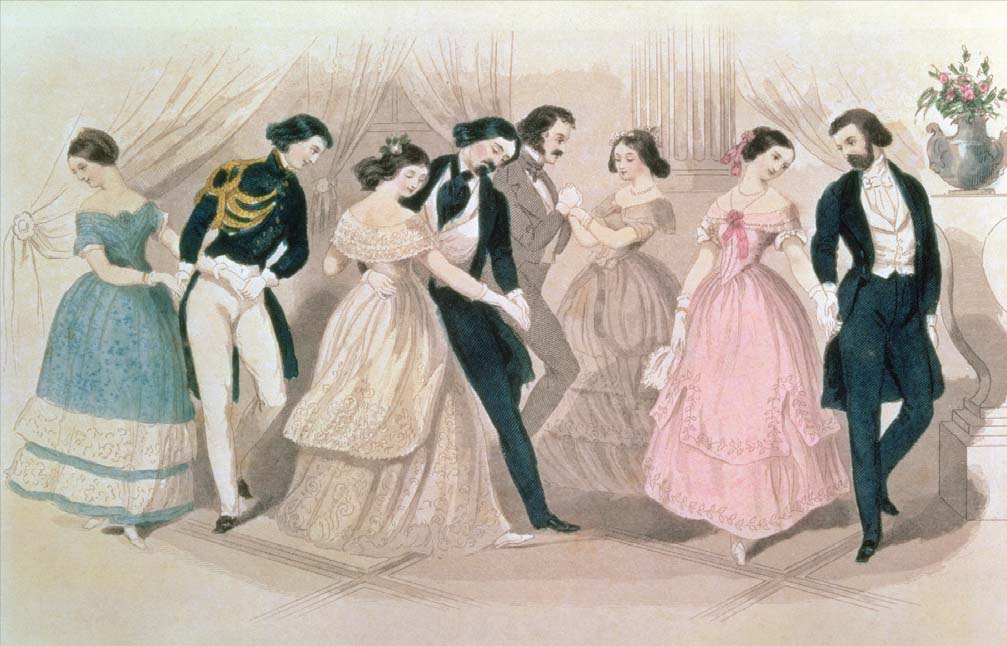

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts, USA/Bequest of Martha C. Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik/Collection of American Paintings, 1815–65/The Bridgeman Art Library.“The Polka Fashions,” from Godey’s Lady’s Book, 1845. “A magazine of elegant literature,” according to its publisher, Louis A. Godey, the Lady’s Book was the most widely circulated American periodical prior to the Civil War and an arbiter of good taste among the aspiring middle classes. Each issue contained a sheet of music for the latest dance craze. The Lady’s Book cautiously endorsed the waltz, a sensuous dance that required a close embrace, but enthusiastically welcomed its cousin, the polka, whose lively tempo and rapid spinning had a wholesome and joyful quality. Introduced from Bohemia, the polka dominated the ballrooms of America’s upper and middle classes in the 1840s and 1850s.

Private Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Private Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library.George Templeton Strong, diary entry, December 23, 1845.

Well, last night I spent at Mrs. Mary Jones’s great ball. Very splendid affair — “the Ball of the Season.” … Two houses open, standing supper table, “dazzling array of beauty and fashion.” “Polka” for the first time brought under my inspection. It’s a kind of insane Tartar jig performed to disagreeable music of an uncivilized character.

Description of juba dancing from Charles Dickens, American Notes for General Circulation, 1842. In New York’s Five Points slum in 1842, Charles Dickens described a challenge dance featuring William Henry Lane, or Master Juba, a young African American who created juba dancing, a blend of Irish jig and African dance moves.

The corpulent black fiddler, and his friend who plays the tambourine, stamp upon the boarding of the small raised orchestra in which they sit, and play a lively measure. Five or six couples come upon the floor, marshalled by a lively young negro, who is the wit of the assembly, and the greatest dancer known. … Instantly the fiddler grins, and goes at it tooth and nail; there is new energy in the tambourine. … Single shuffle, double shuffle, cut and cross-cut; snapping his fingers, rolling his eyes, turning in his knees, presenting the backs of his legs in front, spinning about on his toes and heels like nothing but the man’s fingers on the tambourine; dancing with two left legs, two right legs, two wooden legs, two wire legs, two spring legs — all sorts of legs and no legs — … having danced his partner off her feet, and himself too, he finishes by leaping gloriously on the bar-counter, and calling for something to drink.

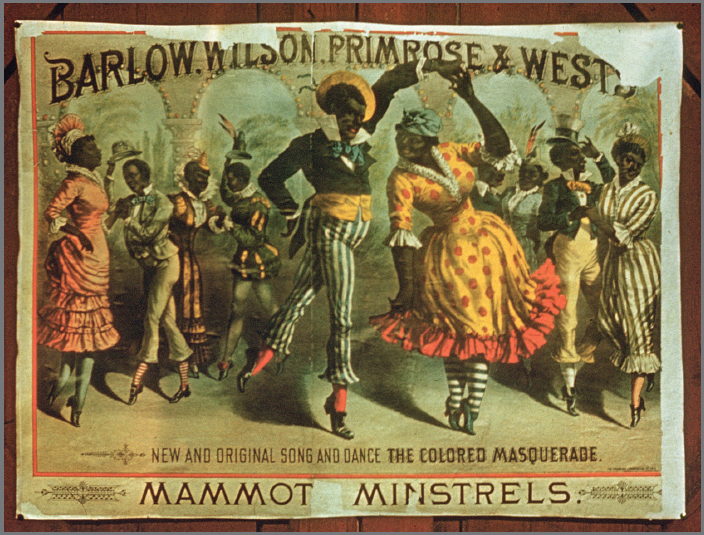

Poster advertising Barlow, Wilson, Primrose, and West’s “Mammoth Minstrels’ Colored Masquerade.” Unlike slavery, minstrelsy survived the Civil War and remained popular until the early twentieth century, when it evolved into vaudeville. Barlow, Wilson, Primrose, and West’s Mammoth Minstrels toured the United States, Europe, and Australia between 1877 and 1882, thrilling audiences with the clog dances that had devolved out of juba.

Private Collection/Photo © Barbara Singer/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Private Collection/Photo © Barbara Singer/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Sources: (3) Luther S. Harris, Around Washington Square: An Illustrated History of Greenwich Village (Baltimore, 2003), 41; (4) Charles Dickens, American Notes and Pictures from Italy (C. Scribner: New York, 1868), 107.

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

Question

What do sources 1 and 2 suggest about sexual manners among rural folk and genteel urbanites?

Question

What does the polka (sources 3 and 4) reveal about changing cultural practices among the social elite?

Question

Compare the juba and minstrelsy dances described above (sources 4 and 5) with the polka and contra dance forms (sources 1 and 2). How were dance forms and popular entertainment evolving? How did those changes relate to broader social developments?

Question

The waltz, polka, and juba dances were popular during the Second Great Awakening, when (and long afterward) preachers often complained that “dance is destructive to Christian life.” Why might ministers (and priests) take such a view? Would any form of dance be acceptable to them?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Question

Using the material on class, religion, and culture in Chapters 9 and 11, the description of the Quarterons Ball in Chapter 12, and the insights you have gathered by a careful inspection of these sources, write an essay showing how dance and other entertainments reflect or reveal differences among American social groups.